Guests

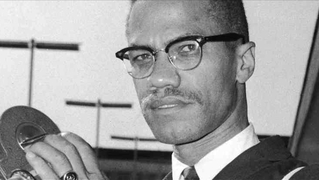

- Ilyasah Shabazzis the daughter of Malcolm X. She was two years old when her father was assassinated. Her new op-ed for The New York Times is called “What Would Malcolm X Think?” She is a community organizer, motivational speaker, activist and author. Her 2003 memoir is Growing Up X.

- A. Peter Baileyis a journalist, author and lecturer. He helped Malcolm X found the Organization of Afro-American Unity and edited its newsletter, Blacklash. Bailey was one of the last people to speak with Malcolm X on the day of his assassination on February 21, 1965. He is the author of Witnessing Brother Malcolm X, the Master Teacher and co-author of Seventh Child: A Family Memoir of Malcolm X. He also helped John Henrik Clarke edit his book, Malcolm X: The Man and His Times.

As Democracy Now! continues to mark the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X, we are joined by his daughter, Ilyasah Shabazz, and friend, A. Peter Bailey. Both were inside the Audubon Ballroom on Feb. 21, 1965, the day Malcolm X was shot dead. Shabazz was just two years old, while Bailey was among the last people to speak with Malcolm X that day.

Shabazz is a community organizer, motivational speaker and author of several books, including the young adult-themed “X: A Novel” and a memoir, “Growing Up X.” Bailey is a journalist, author and lecturer who helped Malcolm X found the Organization of Afro-American Unity and served as one of the pallbearers at his funeral. Bailey is the author of several books, including “Witnessing Brother Malcolm X, the Master Teacher.” Shabazz and Bailey discuss the circumstances surrounding Malcolm X’s killing and share personal reflections on his life and legacy.

Watch Part 1 of the conversation here.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

AARON MATÉ: And I’m Aaron Maté. Welcome to our listeners and viewers around the country and around the world. As Democracy Now! continues to mark the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X, today we spend the show with his daughter, Ilyasah Shabazz, and his friend, A. Peter Bailey. They were both inside the Audubon Ballroom on February 21st, 1965, the day Malcolm was shot dead. Ilyasah was just two years old.

AMY GOODMAN: Ilyasah Shabazz is a community organizer, a motivational speaker, activist and author. She recently co-wrote a young adult book called X: A Novel. Her previous books include Malcolm Little: The Boy Who Grew Up to Become Malcolm X and The Diary of Malcolm X: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. Her 2003 memoir is called Growing Up X. Her latest piece for The New York Times was headlined “What Would Malcolm X Think?” She joins us here in New York.

And from Silver Spring, Maryland, we’re joined by A. Peter Bailey, journalist, author, lecturer, helped Malcolm X found the Organization of Afro-American Unity and edited its newsletter, Blacklash. Bailey was one of the last people to speak with Malcolm X on the day of his assassination. He served as one of the pallbearers at Malcolm’s funeral. He’s the author of Witnessing Brother Malcolm X, the Master Teacher.

We want to welcome you both to Democracy Now! Ilyasah, let’s begin with you. Talk about Malcolm and what you think he would have thought about what’s happening today, Ilyasah.

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Right. Well, it seems that 50 years ago there was an effort to discredit Malcolm and to portray him inaccurately. And so, I think if we would have listened to him, that we would not have this 50 years later. The same type of injustice that we had then, we’re having today. And so, now we have young people saying that black lives matter. I think it was absolutely brilliant that young people could organize, galvanize, strategize and, you know, create these hashtag slogans, that they are organizing, you know, they are being activists and so forth. But I just think that we have to find resolution, that we smart adults have to come together and talk about these things that are happening, that we have to include history, history of African Americans, history of the slave trade, you know, those who found—who helped to cultivate a barren land that we can now today call the United States of America. And so, I think that once we are honest with ourselves and we take responsibility with the things that’s happened here in our country, we will address institutionalized racism, systemic racism. And black lives will—and—you know, I have so much, I want to say it so fast. And that black lives do matter, that all lives matter. And that’s really what my father was—you know, was working toward.

AMY GOODMAN: It is hard to believe that Malcolm, your dad, and Dr. Martin Luther King were both killed at the age of 39, both gunned down at the age of 39.

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Right, that’s correct. That’s correct.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you remember Dr. King’s assassination? You were older then. What, about—actually, not that much older. You were five or six.

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Right, I was. I remember, right, the sadness, because my mother and—we called her Aunt Coretta, they were very close.

AMY GOODMAN: How did they know each other?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Through the movement. You know, both husbands, just such similarities.

AMY GOODMAN: Uh-huh.

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Yeah, they were extremely close.

AARON MATÉ: Can you tell us about your mother, raising six children on her own, going back to school to get her doctorate in education? At the memorial, you spoke very movingly about how instrumental she was in founding the center in the place where your father was killed and in spearheading that beautiful mural on the wall that goes through his life. Can you talk about Dr. Betty Shabazz?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Yes. You know, what was great about my mother is she was—you know, she saw a glass half-full than half-empty. Her motto was “find the good and praise it.” And so, she was able to turn the center of—she was able to turn the Audubon from a place that once represented tragedy into a place of triumph. And it was not so that Malcolm could shine, but so that his work could serve to empower so many generations of people who were psychologically scarred. So my mother, you know, having witnessed her husband’s assassination—a week prior, her home was firebombed with a Molotov cocktail—so she was—you know, had limited funds, limited home, six—well, actually, she had four babies, pregnant with twins. You know, how was this woman able to go forward and not feel bitterness and despair, victimized? And it was because of her self-respect, self-esteem, and not accepting “no” or “I can’t” as an answer.

And I often share that with young people, that there really aren’t many excuses. If there’s something that we want, like social justice or whatever it is we want, that we just have to do the work and persevere until we make it happen, until we choose—until we are successful. So, when it comes to this new—you know, our movement today, that young people must find what is their end goal. You know, so we want to end the systemic racism, but we can’t end it with just hashtag slogans, that we have to keep pushing until we actually address the problem. And that’s why I say, 50 years later, we’re still in the same place, because we try to pretend that Malcolm was this man that he was not. We didn’t look at the social climate. We didn’t look at his reaction to violence perpetrated against his people. We said that he was something that he wasn’t.

AMY GOODMAN: You dedicated your book, X: A Novel, to your nephew Malcolm. Can you talk about your nephew?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Oh, my goodness. I loved my nephew Malcolm as much as I loved my mother and as much as I loved my father. He was a very special young man. And, you know, he had some challenges in his young life. I’m happy that he came to grips with his identity. And he was very much, I think—you know, he used to say to me, “Auntie, my life is like my grandfather’s.” And I said, “Oh, come on, Malcolm. You know, no, it isn’t.” But it actually was. And it was while writing this novel, I reflected on Malcolm and what he had as his foundation, and then—and looked at my father and was just able to—it made it so much easier to write this book.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about what ended up happening with Malcolm.

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Malcolm was killed in Mexico. He was—and this speaks to his integrity. He was invited to Mexico under the premise that the African Mexicans were being discriminated and treated unfairly and that they needed him to, you know, talk to them. And so, he went thinking that he was going to speak to these people, and they ended up killing him.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re still here with Peter Bailey, who’s in Silver Spring, who was one of the last people to talk to Malcolm X on that day that Malcolm was killed, February 21st, 1965. Malcolm X was going to bring the United States to the U.N. Human Rights Commission. Can you explain what his goal was, what he was attempting to do?

A. PETER BAILEY: He was attempting to internationalize the movement, which is why the Organization of Afro-American Unity always described itself as a human rights movement, not a civil rights movement. He was also reacting. And again—and this is very important, because people have a tendency to forget this—during that period, 1955-1965, when he was most active on the scene, that was white terrorism going on in this country, white supremacist terrorism. And he was responding to that. And the federal government was doing practically nothing to stop this terrorism, practically nothing. When they did do a few things, it was only under intense pressure, from international pressure. The United States foreign policy, the Soviet Union was using this, what was going on in this country, against the United States in the international arena. So they—eventually, the federal government, I feel as though they had to do something. Brother Malcolm was well aware of this, being the type of analytical person that he was, so he decided that if we go before the U.N. Commission on Human Rights and put that kind of international pressure, they will be—the federal government will be forced to do much more to protect people who were out there demonstrating and protesting for basic human rights, and also do something to stop the terrorists who were brutalizing people. So that’s what it was all about.

And he tried to—he laid the foundation by going to the OAU conference, the Organization of African Unity conference in Cairo in 1964, and issuing a statement. He was not invited as a participant, but as an observer. And he issued this statement explaining his position. As a result of that, the African leaders of the OAU issued a resolution condemning discrimination in the United States—unheard of. This happened solely because of what—the groundwork laid by Brother Malcolm. Later, in the U.N. debates on the Congo, when the U.S., Belgium and England invaded the Congo ostensibly to save some white nuns, two foreign ministers from Ghana and Guinea, in their U.N. speeches on this, said that, you know, if the United States had the right to do this in the Congo to save these nuns, who’s to say they don’t have the right to help militarily to help black people who are being brutalized in Mississippi? I mean, again, I’m paraphrasing, but that’s what it said. This was unprecedented. So he was making some progress in this move. And if you think of the time, this is the height of the so-called Cold War, when this country was involved in a tremendous propaganda war with the Soviet Union. There were elements in the United States government who were very upset about this. In fact, CNN did a program where they had J. Edgar Hoover saying, “Do something about Malcolm X.”

AARON MATÉ: Mr. Bailey, what was Malcolm X like personally? Can you share some memories of him from your brief time with him?

A. PETER BAILEY: Yes. I mean, to me, he was courteous. He cracked jokes. And one thing that I remember about him, he was concerned about people, and I had a direct incident with that. The day before he was assassinated, February 20th, 1965, I was in our office at 125th Street at the Hotel Theresa. And he came in that day, and I showed him a copy of a press release that I had written about the firebombing of his home and the—him being banned from France. Those two things had happened like right behind each other, the ban from France, then the firebombing. And I don’t know what I said in it, but I must have said something that could have got us jammed up for something we said in it other than what we did. So he asked me to not distribute it at the rally the next day. So I said, “OK,” and put it away. And I didn’t question it, because in the very first issue of the newsletter, I had called—said “eyewitnesses to the murder” in referring to the shooting of young Powell by the cop that led to the Harlem uprising, and he had told me, “You can’t use 'murder,' because 'murder,' legal terms, and you’ll be sued, and—calling him a 'killer' and referring to it as a 'killing.'” This is the master teacher in action.

So when he came in that day, he asked me to come backstage, as I said earlier. I went backstage. And this is what I tell students. This brother was under all this pressure. All this pressure he was under. And yet he said to me, “Brother Peter, I know you put a lot of work in what you did, you know, with the thing that you wrote yesterday. I hope you understood why I asked you to not distribute it.” He was concerned about my feelings, under all that pressure. That’s Brother Malcolm to me. That’s Brother Malcolm to me.

He was wise. He told us, if we have a meeting and a rally, and the—someone stands up at our meeting or rally and said, “We ought to go bomb the subways,” to put that person out, because nine times out of 10 that person is a plant, designed to get us caught up in saying things that will get us, you know, jailed. And I thought about that recently when I watched the demonstrations in New York around the whole Garner killing, and all of a sudden the people in some rally started yelling, “What do we want? Dead cops! When do we want it? Now!” And I’d be willing to bet—you know, thinking about what Brother Malcolm taught us, I’d be willing to bet you that those were plants.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, speaking—

A. PETER BAILEY: And that any—

AMY GOODMAN: Speaking of that, Malcolm was followed when he was in Africa. He kept seeing the same guy over and over.

A. PETER BAILEY: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Ilyasah, I wanted to ask you about this, and, Peter Bailey, if you’d like to weigh in, in The Diary of Malcolm X: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, 1964, who was this person that he kept seeing?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: I don’t think we said in the book, you know, so I don’t know that I’m at liberty to say. Peter—

AMY GOODMAN: Uh-huh. You know who he is?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Peter, do you know who he is?

A. PETER BAILEY: He wasn’t talking about—it wasn’t a person. It was a government agent. We don’t—I don’t know the name of the person. But he was—he had a confrontation with the ambassador to Kenya, who told him, “You have no right to come over here.” I think his name was G. Mennen Williams, if I remember correctly. “You have no right to come over here and, quote-unquote—and affect our foreign policy.” And Brother Malcolm said, “Well, if you were not doing the things that were going on in the United States, you wouldn’t have to be concerned about what I say.” So the United States, they were very concerned about what he was doing to internationalize the movement. He was invited to speak to the king in Parliament. I mean, he was treated almost like he was a foreign minister of black people in America to the world. And this greatly disturbed people in the United States government.

AMY GOODMAN: The Autobiography of Malcolm X might surprise many, especially younger people, to know it was published after he was killed. Can you, Ilyasah, talk about the effect this had—I mean, this is how so many people came to know Malcolm, his evolution—and how that book came to be published?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Well, he was asked to write this book when he was with the Nation of Islam. And towards the end of writing the book, he was suspended and began—and it actually became an autobiography of his own life. I know that many people have been quite affected by this autobiography or by my father’s life.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Peter Bailey, if you could talk about the significance of this book coming out after Malcolm was killed?

A. PETER BAILEY: Well, I think, because it broadened—it gave people a broader view of him. This whole image of him that was depicted in the press at that time that he advocated violence and that—when he was advocating self-defense, but they called advocating self-defense advocating violence, that they made him sound as though he spoke, you know, almost irrationally, he was making things—saying things that were not true. Everything he said was based in fact. This brother was a person who knew—he knew the legal system and how it worked. He knew the international system. He studied. He learned.

So he was—and, see, this is what young people also need to understand. Brother Malcolm was about discipline. This kind of impromptu, you know, just bouncing around and everybody doing their own thing—you know, if you’re going to have a serious movement, you’ve got to have discipline. And he was about discipline. Those of us with him in the OAAU, we—you know, there were certain things you were supposed to do and a certain time when you’re supposed to do them. That was a discipline imposed on us. We were all rather young. We were like in our—in your early to mid-twenties, most of us. And he gave us a kind of discipline. And I look so many times at, “Well, you know, everybody do their own thing. We’re going”—no, you can’t do your own thing and have a successful movement. And young people need to understand that. You have to have people—you have to have a group of people who are prepared to get—and he taught us that. And I think the autobiography explains some of that.

I mean, this whole idea you hear constantly about him—you know, they try to make it sound like he went through the St. Paul on the road to Damascus changes. They were not. He was on a very consistent path. If he saw something that was—he had a position that was unintelligent, then he would drop it. Nobody who’s intelligent holds onto a position that is no longer, you know, viable. You know, that doesn’t mean that the person is going through some kind of tremendous evolution, a change. And people always are trying to use that to say, oh, well, he was doing this, and he was doing that. No, he was the same person.

He was a black nationalist. And people don’t like to hear that. Now, does that mean that you think that black people will get into some kind of little enclave and work all about themselves? Of course not. But it means that you have a strong sense of group identity, you work to improve the position of your group, so that you can effectively work and negotiate with members of other groups. Only an idiot would think that black people can get in some kind of little enclave all by themselves, which is the way they always try to depict anyone who talks about black nationalism, as though we are kind of unrealistic about how the world functions. We have a very real view of how the world functions. And we believe in forming alliances with other people with whom we might share on different issues. But we also believe that it’s necessary for us as a people to have a strong sense of a purpose and unity and group identity.

AARON MATÉ: Ilyasah, your father is revered around the world. Millions of people love him and cite his work often. Is that strange to have to, in some ways, share your father with this giant mass of people across the globe?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: No, not at all. I understand the importance of my father’s work and how he has inspired so many. So, not at all. Including Peter Bailey.

AARON MATÉ: What kind of reaction do you get from people when they talk to you about your father?

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who reacted in a negative way. I would say, for the most part, you know, again, it’s just how much they’ve admired the work, how he inspired them, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you both for being with us—

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: —for spending this time. Ilyasah Shabazz is the daughter of Malcolm X, the third daughter. She was two years old when her father was assassinated in the Audubon Ballroom. She was there with her mom and her two older sisters. She’s written a piece in The New York Times, which we’ll link to, called “What Would Malcolm X Think?” And she recently co-wrote a young adults book, which has become a best-seller, called X: A Novel. She also co-edited, with Herb Boyd, The Diary of Malcolm X: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. A. Peter Bailey, thanks so much for being with us, journalist, author and lecturer, founding member of the Organization of Afro-American Unity with Malcolm X, edited its newspaper, Blacklash. Bailey was one of the last people to speak with Malcolm X on the day of his assassination. He served as one of the pallbearers at Malcolm’s funeral. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Aaron Maté.

Media Options