Topics

Guests

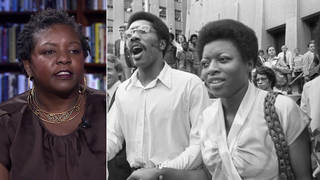

- Cynthia Roseberrydirector of the Clemency Project 2014. Her organization helps train lawyers to file clemency petitions for nonviolent drug offenders. Some of those petitions were among those granted Thursday.

- Reynolds Wintersmithrestorative justice counselor at CCA Academy, a high school in Chicago. In 1994 he was sentenced to life in prison at age 20 for selling crack — his first offense. President Obama granted him clemency on January 1, 2014.

We end today’s show with a new push by the White House to support bipartisan prison reform — this time by reducing punishments for nonviolent crimes. On Thursday, President Obama granted clemency to 46 prisoners, including 14 who faced life without parole. Many of the commutations went to crack offenders, including one African-American man who is 84 years old, and the mother of Denver Broncos wide receiver Demaryius Thomas. President Obama has now commuted 89 sentences, including 22 drug offenders who were granted release earlier this year and eight others in 2014. He is expected to call for more fairness in the criminal justice system when he speaks today at the annual convention of the NAACP. This Thursday he will become the first president to visit a federal prison when he tours the El Reno facility in Oklahoma. We speak to Cynthia Roseberry, director of the Clemency Project 2014, and Reynolds Wintersmith, who once faced life in prison for selling crack but was freed last year after receiving clemency.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We move now to our last segment—this is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report—to a new move by President Obama. We end today’s show with a new push by the White House to support bipartisan prison reform—this time by reducing punishments for nonviolent crimes. On Thursday, President Obama granted clemency to 46 prisoners, including 14 who faced life without parole. Many of the commutations went to crack offenders, including one African-American man who’s 84 years old, and the mother of Denver Broncos wide receiver Demaryius Thomas. President Obama has now commuted 89 sentences, including 22 drug offenders who were granted release earlier this year and eight others in 2014. He’s expected to call for more fairness in the criminal justice system when he speaks today at the annual convention of the NAACP. This Thursday, he’ll become the first president to visit a federal prison when he tours the El Reno facility in Oklahoma.

For more, we go to Washington, D.C., to Cynthia Roseberry, director of the Clemency Project 2014. Her organization helps train lawyers to file clemency petitions for nonviolent drug offenders. Some of those petitions were among those granted Thursday. And in Chicago, we’re joined by Reynolds Wintersmith, who once faced life in prison for selling crack, but was granted a new beginning in 2014 when President Obama commuted his sentence. Wintersmith was just 17 in '94 when he was arrested. It was his first offense. He's now a restorative justice counselor at CCA Academy, a high school in Chicago.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! In Washington, D.C., let’s begin, Cynthia Roseberry, with you. Talk about the people who were just granted clemency.

CYNTHIA ROSEBERRY: Sure. Many of them were convicted under draconian drug laws—and I would say that Clemency Project 2014 is not limited to drug offenders—but most of those laws have changed now. So this initiative gave hope to people who never thought they’d be reunited with their families, who were given life sentences or very long sentences for nonviolent offenses.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, talk about the significance of what President Obama is doing. And did you work with the White House in choosing the names of the people who would get clemency?

CYNTHIA ROSEBERRY: No, we’re wholly separate from the White House. We are an initiative of the American Bar Association, the American Civil Liberties Union, Families Against a Mandatory Minimum, national Public and Community Defenders and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. So we work wholly independently of the White House. But we screen applicants—we have more than 30,000 now—to see if they appear to qualify under the president’s initiative, and then we send those petitions over to the pardon attorney.

AMY GOODMAN: Reynolds Wintersmith, tell us your story, having once faced life in prison for selling crack. But talk about what the clemency that President Obama granted you, or the commutation of your sentence, what it means.

REYNOLDS WINTERSMITH: Well, to me, what it meant, it gave me another chance at life, to build upon this part of my life in the present. You know, I’m thankful for it. It made me realize that even when we have the possibility of failure in front of us, that doesn’t mean that we should give up hope. We should continue to strive, you know, make it easier for a person to want to give you a second chance. And I’m thankful for it.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the sentencing for nonviolent drug offenders like yourself?

REYNOLDS WINTERSMITH: Yes. Well, first, I would like to say that I believe in law and order. I believe in structure. So I understand the effects that it had on the community, on the lives of the people. But far as sentencing, when you come before a judge and he passes out a sentence to you, the only thing that you will hope for is to have a fairness in it, a balance. And a lot of times with the drug sentences, you know there is no balance. When I got sentenced in 1994 in November, there was no extraordinary circumstances that they could bring up, because of the sentencing guidelines. They were mandatory at the time. So it was just numbers computed and implemented, and I was given a sentence of life and 40 years for a Count One conspiracy and in a Count Four that was on the conspiracy. So, I mean, with this new criteria that President Obama has set forth for clemency, it has made it possible for people to reach forward, you know, to believe that they can have another chance, as we all know that the backlog of clemency petitions runs in the tens of thousands.

AMY GOODMAN: Reynolds, how did you get the clemency? You had already been in jail already for what? Like 18 years?

REYNOLDS WINTERSMITH: Yes. Well, the process began long before I even filed paperwork. I worked for a lady in the education department. Her name was Janice Feaster [phon.]. I was a tutor. And, you know, we had dialogue. And a guy, Prior Reed [Reed Prior], President Bush had pardoned. He had a life sentence. He had been in prison for eight years. And so, when we said—when she told me what happened with him, because he worked with us as a leisure library clerk, she told me that “Why don’t you file for clemency? Your story is a different kind of story?” And, you know, at the time, facing all the things from my own past and still being held accountable for it, you know, it was hard for me to see why would they give me another chance. You know, I had faced issues in prison, such as classes—

AMY GOODMAN: We have 10 seconds.

REYNOLDS WINTERSMITH: OK. And so, it was a process. I’m glad that I had a great support group. And then I had an attorney, MiAngel Cody, that said, yes, she would help me.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we will continue to follow what happens this week with President Obama being the first sitting president to visit a prison, that in Oklahoma. Reynolds Wintersmith and Cynthia Roseberry, thanks so much for being with us.

Media Options