Related

Topics

Guests

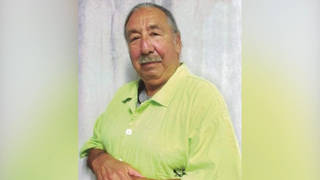

- Michalis Spourdalakisprofessor of political science at Athens University and a founding member of Syriza.

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras is facing protests from members of his own Syriza party after accepting harsh austerity measures in exchange for a new international bailout. In order for the deal to move forward, the Greek Parliament must accept pension cuts and other reforms by Wednesday, 10 days after voters rejected similar reforms in a referendum. On Monday, Greek Defense Minister Panos Kammenos accused Germany of staging a coup. We speak to Michalis Spourdalakis, professor of political science at Athens University and a founding member of Syriza.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We go to Greece, where Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras is facing protests from members of his own Syriza party after accepting harsh austerity measures in exchange for a new international bailout. In order for the deal to move forward, the Greek Parliament must accept pension cuts and other reforms by Wednesday, 10 days after voters rejected similar reforms in a referendum. After European leaders pressed Greece to accept the austerity package, the hashtag #ThisIsACoup trended on social media. Greek Defense Minister Panos Kammenos accused Germany of staging a coup.

DEFENSE MINISTER PANOS KAMMENOS: [translated] Yesterday, the country’s prime minister faced a coup, a coup by Germany, but also by other countries like the Netherlands, Finland and the Baltic states, a coup that reached the point that Greece’s prime minister was blackmailed with the collapse of the banks and a haircut on deposits. I want to be clear that this deal is beyond the agreement that political leaders made with the Greek president and that the Greek Parliament approved. However, this agreement, which also brought up new information, speaks of 50 billion euros’ worth of guarantees concerning public property. It speaks of changes to the law, including the confiscation of homes. It refers to a total collapse of constitutional values. We cannot agree to that.

AMY GOODMAN: Speaking Monday, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras said Greece was left with little choice but to accept the austerity measures.

PRIME MINISTER ALEXIS TSIPRAS: [translated] We fought hard for six months, and until the end we battled to get an agreement, to get the country back on its feet. We were faced with a very difficult decision within hard dilemmas. We took the responsibility to decide, in order to avert the most extreme plans by conservative circles in the European Union. Today’s agreement keeps Greece in a state of financial stability. It gives the possibilities for a recovery. It will, however, be an agreement whose implementation will be difficult. The measures included are the ones passed in Parliament. They will unavoidably cause recessionary effects. I have the feeling, the confidence and the hope that the 35-billion-euro development package, which we managed, along with the debt restructuring and the secure financing for the next three years, will create the feeling among markets and investors that Greek exit is a thing of the past.

AMY GOODMAN: To talk more about the implications of the agreement, we go to Athens, Greece, where we’re joined by Michalis Spourdalakis, professor of political science at Athens University. He’s also a founding member of Syriza.

Welcome to Democracy Now! It looks like there is a split not only among the Greek people, Michalis Spourdalakis, but also in your own party itself. Talk about the deal and what it means.

MICHALIS SPOURDALAKIS: Well, it’s only natural to expect these objections to the deal, because it’s a deal which imposes draconian measures to the Greek economy, and also, people, after the referendum, were hoping for a much better deal. Except it seems to me that the Europeans didn’t take into account the very loud, clear “no” vote, no-to-austerity vote, casted just 10 days ago from today. Therefore, everything that your report says, it’s true: The Greek prime minister and the country’s minister of finance were actually blackmailed by the eurozone people. They managed to convince some of them, but not all of them, so at the end of the day they got this deal, which is not only draconian—it will continue the recession in the country—but also will be inefficient. It’s a deal that, at the end of the day—or, I should say, quite soon—there are going to be more measures imposed, increases the debt of the country. And I don’t think we’re going to—we see the light at the end of the tunnel.

But the prime minister had no choice, because the alternative was to exit. But exit would lead us to a more Hobbesian type of social development that this country has no experience or preparation, moral or technical, to confront.

AMY GOODMAN: The term “Grexit,” right, the Greek exit. So, right now, this hashtag that’s trending, #ThisIsACoup, explain what’s going on. And will this lead to the fall of Syriza?

MICHALIS SPOURDALAKIS: Well, I hope not. This is the first left-wing government in this country. This is the first democratic response to the austerity measures in Europe. So, this government should not—should not fall. It’s very superficial and very—at least unfair conclusion to claim that the prime minister or the government has betrayed the people. They were forced to do that. There are all sorts of other fields that the government can verify or reinstate its left-wing radical orientation, and this is the way the government should proceed. Pretty soon, the people are going to face—or the Greek government, rather, is going to be faced with more measures, and by then, probably, the balance of power are going to be different.

As of the coup, OK, there many interpretations about this coup. I read someplace today that some 48 years ago the dictatorship was imposed in this country by the guns of the colonels, at the time, of the army. Today, the coup is imposed by the European bankers, who managed to close the Greek banks and have the entire Greek society hostage. So, to me, there was no—there was no alternative, not been prepared.

But there is another coup, which has to do with the future of the European Union and the future—the perspective of developing European Union in a democratic way. There is a major, a major coup, because it seems to me that the European leaders undermined the fact or didn’t pay any attention to the fact that in Greece, that was the only country that there was a democratic response to austerity, while in every other—almost in every other European countries, probably with the exception of Spain and Ireland, the political rearrangement had—gave signs and gave room to the right-wing populist euroskepticism, and even neo-Nazism. And it seems to me that the European leadership, it’s more tolerant to these developments than the radical-left—however, democratic—response to austerity in Europe. And this is very disappointing. And this is another dimension of the coup.

AMY GOODMAN: Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem defended the troika of European and International Monetary Fund lenders against accusations that they interfered in Greece’s domestic politics.

JEROEN DIJSSELBLOEM: Perhaps I can also say something on this issue, because I’ve always felt that the troika has been heavily criticized on the fact that they sort of interfere with domestic politics and are very intrusive. But, of course, in the given situation, the crisis situation that we have, in case of a program, per definition, we always try and find the balance between supporting a country, but also talking about reasonable and effective conditionalities. There’s not much point in borrowing money to a country—or lending to a country, if at the same time the underlying problems are not dealt with. And I think that’s a fair balance, and we have to find that. So it’s not about taking over a country. It has to be a partnership and commitment on both sides to stand ready to further support the country—in this case, Greece—and for Greece to say, “We will do what it takes on our part to make sure that we don’t depend on European loans forever.”

AMY GOODMAN: I would like to get your response, Michalis Spourdalakis, to the Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem’s response.

MICHALIS SPOURDALAKIS: Yeah, OK. I think this agreement guarantees that the country is going to stay, at least for the time being, tied to further dependency to European loans. It’s impossible—listen, the country had about $340 billion debt. No one in his right mind, his or her right mind, thinks that this is a manageable debt. Now, there is another 83, if I’m not mistaken, billion euros added to this loan. So I don’t know how we’re going to pay that.

You mentioned the 50 billion euros guarantees, or collateral. OK, listen, the breakdown of this is about 29 to 30 billion are going to go into repaying the old debt. About 17 billion, or 17 to 18 billion, are just the interest rates. There is another 20-some million who is going to—for support of the banking system. And the rest is going to be for development. In addition, these 50 billion euros are going to come from selling Greek property—Greek airports, peripheral airports, the three major ports in Greece and other valuable parts of the Greek infrastructure. This money, it’s impossible to raise. Even if you sell the entire country—well, of course, I’m exaggerating—you’re not going to get more than eight, maybe 10, billion euros.

So, this is a deal which is not going to be efficient. It doesn’t deal with the actual fiscal problems of the country or the economic problems of the country. It’s a very vindictive, however, deal, which really wants to force the government to change its political orientation, or wants to bring—clearly, to bring the first radical left-wing government down. That’s why it should—this deal should be—no matter what the criticism is, this deal should be supported, because pretty soon there’s going to be a new round, and then probably we’ll be ready to respond to the pressures of the European Union and the Eurogroup in a more efficient and a more democratic and socially sensitive way than what this deal promises.

AMY GOODMAN: Michalis Spourdalakis, I wanted to get your take on a letter that Robert Reich, the former labor secretary under President Clinton, has sent around. He says, “People seem to forget that the Greek debt crisis—which is becoming a European and even possibly a world economic crisis—grew out of a deal with Goldman Sachs, engineered by Goldman’s Lloyd Blankfein.” He said, “Several years ago, Blankfein and his Goldman team helped Greece hide the true extent of its debt—and in the process almost doubled it.” He said, “Undoubtedly, Greece suffers from years of corruption and tax avoidance by its wealthy. But Goldman Sachs isn’t exactly innocent. It padded its profits by catastrophically leveraging up the global economy with secret, off-balance-sheet debt deals.”

And then he makes recommendations. He says that the U.S., you know, is a key player in the IMF, and President Obama should use that weight, that people should “[j]oin with allies across Europe to show solidarity with the Greek people and stand up to global austerity.”

Can you respond to the issue of Goldman Sachs and hedge funds and their role in this? We actually only have a minute.

MICHALIS SPOURDALAKIS: This is a—yeah, this is an old story. We all know the tricks and the corruption involved in the way that Greece met the requirements to enter the eurozone. And since you mention corruption, it’s quite interesting to respond about the issue like that. Corruption is the basis upon which the Greek economy, the Greek capitalism, flourishes and reproduces itself. And tackle corruption, tax evasion and the rest was the first reform that the Syriza government proposed to our—to Greece—to the country’s debtors back in the early February. And they didn’t really pay much attention to it. So, it seems to me that the bottom line of all this debate is that the country’s debtors wanted to humiliate Syriza, Tsipras, and, as I said already—twice, I think—the first democratic, left-wing response against austerity in the 21st century. That’s the bottom line. There is a lot of corruption in this country. This government has been committed to tackle the corruption. But the way that the proposals that are imposed and the deals are imposed by our debtors, they are not—I don’t predict that they are very efficient moving towards that way. So, we’ll be—

AMY GOODMAN: Michalis—

MICHALIS SPOURDALAKIS: We’ll come back on the issue again.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to—I want to thank you for being with us, and I hope we come back to this conversation. Michalis Spourdalakis, professor of political science at Athens University, also a founding member of Syriza.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, we got to Madison, Wisconsin. Governor Walker makes 15. That’s 15 Republican presidential candidates. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

Media Options