Guests

- Sarah Shourdjournalist, playwright and University of California at Berkeley visiting scholar. She spent 410 days in solitary confinement while held as a political hostage by the Iranian government from 2009 to 2010. Since her release from prison five years ago, Shourd’s work has focused on exposing and condemning the cruelty and overuse of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons.

Since her 2010 release from an Iranian prison, Sarah Shourd’s work has focused largely on exposing and condemning the cruelty and overuse of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons. She has just written a play about solitary confinement in the United States titled “Opening the Box.” It was performed Thursday at an event hosted by the Fortune Society in New York City, before an audience of many who had been in solitary.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: You have been focusing on solitary confinement since you left. I mean, many in your circumstance would get as far away as they could of the circumstances that you lived through when you were in Iran, but you’ve actually really drilled down into it and looked here in the United States. Talk about your project.

SARAH SHOURD: Sure. Well, when I was imprisoned in solitary confinement, any chance I would get to see my captors, I would say, “What you’re doing is torture. What you’re doing is illegal. I can feel that—I know that something is happening to my brain. I can no longer focus on a book for more than a few minutes without getting frustrated, because I have to read the same paragraph again and again.”

AMY GOODMAN: Which means? Why did you have to read the whole—

SARAH SHOURD: I mean, scientific studies are really still not—there haven’t been enough of them, but there have been studies that show, after just two or three days, your brain starts to shift towards delirium and stupor. Being in that kind of isolation is—you start to lose sense of who you are, of your values. Our identity as people is in relation to other people, through conversations, through work that we do in the world. In that kind of isolation, it’s very easy to just completely succumb to depression. And that’s why suicide in solitary confinement is twice as high as in the rest of the prison population in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: So talk about Opening the Box.

SARAH SHOURD: Well, it’s been several years now. I started researching—really, it was part of my own—when I got out and I saw that solitary confinement doesn’t just happen in places like Iran. Actually, in this country we have far more people in solitary confinement than any country in the world per capita and any country in history for far longer periods of time. So, I was in isolation for 410 days. The U.N. special rapporteur against torture says that 15 days can cause permanent, lasting damage. People in this country are held for years, for decades in some cases. And one of the most important things for me in my own—in moving forward in an empowering way was to talk to other survivors, was to find out that, you know, talking to yourself, naming your body parts, having—you know, feeling an emotional connection to an insect that happens to make its way into your cell is not strange at all, that we all experience these kinds of horrors. And so, talking to other people led to interviews, and I started to collect these stories. And I wove them into this play, Opening the Box.

AMY GOODMAN: So you traveled across the country, speaking to people in solitary confinement?

SARAH SHOURD: I did, yeah. The first six months, I had 12 very in-depth letter correspondences. I was writing multiple letters a day and found some of the most incredibly creative, amazing people that expressed themselves so eloquently, in many cases, through the written word, because that’s their only method of communicating with the outside world, so just pouring their souls into these letters. And I tried to visit as many as I could, as many as I could get permission to—New York; New Jersey; of course, Pelican Bay in California I went to many times—and developed these amazing relationships and wove them into a fictional account of resistance behind bars.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to the reading of your new play, Opening the Box. This is a clip from the event last week, Thursday night, hosted by Fortune Society in New York, which helps people re-enter society after they get out of prison. So that was the audience. Many in the audience had been in prison. Many had been in solitary. This is a scene with a character by the name of Rocky, a young prisoner, and this is his reaction when he just learns that he has been remanded to solitary confinement for 18 months.

ROCKY: I’d rather be somebody else. I’ve always felt that way, a different guy on a whole different planet. I sit here hating all the people that have what I’ve never had. It’s like I’m a virus no one can touch. I mean, like a tree in a forest thing. Who says I even exist? My brain is like oatmeal. My brain is a piece of [bleep]! What do I have left? My finger touching another finger, the color red when the lights hit the back of my eyes, words on repeat and repeat. I think of my Julia every minute, and every [bleep] time there’s a pain in my chest like being stabbed. I’d cut off a finger to see her. I’d cut my whole [bleep] hand. Why do I sit here in pain asking for more pain? This [bleep] toilet! This [bleep] bed! How can they be so lucky? They can’t feel nothing! I can hit them. I can kick them. They don’t feel nothing! I’d swear I’d rather be punched in the face every minute of the day than have to sit here just feeling! Get me out of here! Get me out of this [bleep] skin!

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Rocky from Opening the Box, Sarah Shourd’s play. Tell us about Rocky and who he’s based on.

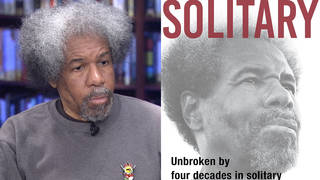

SARAH SHOURD: Well, he was—so I had got access to recordings of Herman Wallace from the Angola Three, part of what was recorded for the film Herman’s House. And one of the characters—one of the people that—

AMY GOODMAN: Herman Wallace, of course, a man who was held more than 40 years in solitary confinement, ultimately died a few days after—he was dying of cancer, which is why he was released from prison and ultimately died a free man.

SARAH SHOURD: Yeah. And it was incredible to be able to get these recordings and just immerse myself in his voice and create this character. So, Rocky is based on a young man that Herman Wallace helped inside. That was a large part of his identity. Whenever a new young person would come into the pod, he would reach out to them, give them advice on how to cope, tell them, you know, basically the rules, how this pod works. And that’s the relationship between Rocky and the character of Ray Duval in my play.

AMY GOODMAN: And who played Rocky here?

SARAH SHOURD: Oh, he is a friend of a friend. He came out of the woodwork. He’s a wonderful young actor. I actually really hope that I can get him to come to the premiere in San Francisco.

AMY GOODMAN: And what are you hoping to do with Opening the Box? That was just one performance. You’re performing it in different places around the country, excerpts of it?

SARAH SHOURD: Yeah, yeah. We are working towards production. It’s going to premiere—the world premiere will be in San Francisco next July, July 2016, at Z Space. And so, I mean, I think that there’s been a lot of attention, you know, comparatively speaking, on solitary confinement in the last five years. Momentum has been building. People know the facts. But I feel like there’s still a lack of actual stories of who the people are that end up in the deep end of our prison system, in the worst punishment that we mete out. And so, I feel like these—that’s a role that I can play. I mean, the high-profile nature of my case meant that I got a tremendous amount of attention. When we performed at the Fortune Society, it was for an audience of people, many of which has—no one has ever asked them what it was like for them. No one has ever asked them to talk about what happened to them in there.

Media Options