Topics

Guests

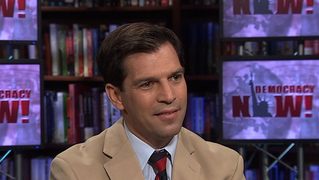

- Jeff Smithauthor of the new book, Mr. Smith Goes to Prison: What My Year Behind Bars Taught Me About America’s Prison Crisis. He is a former Missouri state senator and now teaches at The New School in New York. Smith is on the board of the nonprofit organization Prison Entrepreneurship Program, or PEP. He’s also the author of the e-book, Ferguson in Black and White.

Extended discussion with former Missouri state Senator Jeff Smith, author of the new book, “Mr. Smith Goes to Prison: What My Year Behind Bars Taught Me About America’s Prison Crisis.” Smith was elected state senator in 2006 and served until 2009, when he pleaded guilty to conspiracy for an election law violation tied to the 2004 campaign. Smith was sentenced to one year and a day in a Kentucky federal prison. He describes his new book as “a scathing indictment of a system that teaches prisoners to be better criminals instead of better citizens.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. This is part two of our interview with Jeff Smith. He’s author of the new book, Mr. Smith Goes to Prison: What My Year Behind Bars Taught Me About America’s Prison Crisis. He’s also a former Missouri state senator, now teaching at The New School here in New York. Jeff Smith is on the board of the nonprofit organization Prison Entrepreneurship Program, or PEP. He’s also the author of the e-book, Ferguson in Black and White.

There’s a lot to get to, but before we talk about Ferguson, before we talk about prison reform and the organization you’re a part of, Jeff, what was the first thing that happened when you went to prison? You were sent to prison for campaign election violations, and you were sentenced to a year and a day.

JEFF SMITH: So, I’ll tell you the first two things that happened. First you walk up the compound, and it’s exactly like it is in the movies on the prison yard—just people screaming at you, all kinds of noise, and all the sort of what they call the fresh fish walk up the yard, and everyone sort of inspects them and hollers at them. And that’s a little intimidating.

Very quickly after that, they show you a video. They show all the new inmates a video. And the video features a middle-aged man who tells his story about coming to prison and eating a Snickers bar that was placed on his pillow in his first week. He was, soon after that, raped. And he explains that accepting sweets from anyone in prison is tantamount to an expression of willingness to have sex, and advises anyone, “Do not eat sweets offered to you.” So that was a pretty important early lesson that I learned.

AMY GOODMAN: So the issue of prison reform and where it’s going in this country today, what were your thoughts on President Obama being the first sitting president to actually go into a federal prison?

JEFF SMITH: I was thrilled. I thought, symbolically, it’s a really important thing for a president to do, and I suspect that prisoners throughout the country probably agreed. At the same time, the president has been a little bit slow to act on some of the reforms that he’s hoped to implement. I understand that he probably felt that there were electoral considerations to not embark on some of this during his first term, but the irony is that some of the leaders on prison reform in this country have actually been conservative Southern Republican governors, not exactly the person you’d think. Rick Perry has a great record, a pretty solid record, on prison reform in Texas. Nathan Deal, the governor of Georgia, he and Perry have both done sentencing reform. They’ve closed prisons. And they’ve reduced recidivism rates by paying much closer attention to re-entry.

AMY GOODMAN: And what is driving this movement? What is bringing together progressives and everyone from Newt Gingrich to the Koch brothers?

JEFF SMITH: Right, so, the conservative movement, I think, in modern politics, it really has three strains: It has libertarians, it’s got Christian conservatives, and it’s got Wall Street kind of economic conservatives. And each one of those strains of the conservative movement has a reason to be for prison reform. Libertarians, like Rand Paul, don’t like overcriminalization and overpolicing, and have fought for sentencing reform and drug decriminalization. Christian conservatives, led by people like Charles Colson, have really paid attention to the moral side of this equation and have talked about the redemption that all humans should get a chance for after prison. And economic conservatives, like a lot of these Southern Republican governors, have said, “You know what? We can’t afford to spend $80 billion as a country on our prison system, when we’re getting such terrible results.” Two out of three people are re-offending. Any businessman would look at a business like that and say, “Hey, if we’re only getting the result we want a third or less of the time, we’re doing something wrong.” So, that’s, I think, the politics that’s brought the conservative movement along, and some liberals, though not all, have joined them.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, isn’t prison big business?

JEFF SMITH: Prison is big business. They’re—

AMY GOODMAN: And you’ve got the for-profit prisons like GEO, like the Corrections Corporation of America—

JEFF SMITH: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —that are making a fortune, with human beings virtually as the private property of these for-profit companies.

JEFF SMITH: Yeah, it’s crazy, and I talked a little bit about the—one component of prison that’s so detrimental to successful re-entry is the way that we make it increasingly difficult for people to stay in touch with their loved ones, by making phone calls extremely expensive or even getting rid of in-person visits and substituting video visits, which are also a profit center for private companies.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, it’s interesting you raise that. I was just in South Carolina, in Columbia, South Carolina. Bree Newsome is this young African-American activist who scaled the Confederate flagpole on the state grounds of the Columbia state House, and she pulled down the Confederate flag. This is before they voted it down. And she said, “This flag comes down today.” So, she was sent to jail. And I went to the jail to see her hearing. And in the waiting room were this line of video screens, and people were lined up at them, talking to their loved ones behind bars. They weren’t talking to them in a room; they were talking through these video screens.

JEFF SMITH: And the prisons sell that by saying, “Oh, this is a security measure. This ensures that no contraband could ever be smuggled into the prison, and it also helps ensure that people who otherwise wouldn’t be able to make a trip to see their loved ones behind bars can now see them through video screens. What they don’t tell you is how much money people are making off that, and the fact that, you know, there’s something about basic human contact and being able to see and touch someone that can really sustain someone.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to stick with the issue of policy. At a speech at the NAACP earlier this year, former President Bill Clinton said he regrets signing the three-strikes law and other legislation that dramatically increased prison sentences.

BILL CLINTON: I signed a bill that made the problem worse, and I want to admit it. … In that bill, there were longer sentences. And most of these people are in prison under state law, but the federal law set a trend. And that was overdone. We were wrong about that.

AMY GOODMAN: So that was President Bill Clinton, a little late, but an apology. Your thoughts on this, Jeff Smith?

JEFF SMITH: Well, first of all, given the present context, we should remember that it wasn’t just Bill Clinton. Hillary Clinton was one of his chief advocates pressing for the three-strikes law to be included as part of the 1994 crime bill.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain.

JEFF SMITH: She’s on the record as being someone who was pressing legislators to vote for this bill and, publicly, as an advocate, saying it’s important to keep three strikes in the bill. So, she’s not totally—it’s not just about Bill. But I do think it’s very notable that something that he called a signature achievement for a long time and something that Bill Clinton and other so-called New Democrats used, credited the decrease in crime, in part, to this crime bill, are now apologizing for it being too draconian.

AMY GOODMAN: He said he was wrong, just to be clear, in this clip. He didn’t exactly apologize.

JEFF SMITH: OK. I stand corrected. I apologize. But it’s notable, and it’s great to see Hillary Clinton come around on the issue. We saw one of her boldest policy moves of the campaign so far was her speech about criminal justice reform. So—and Martin O’Malley has put out a fantastic platform. I had a part in advising him on that, and so—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean?

JEFF SMITH: I’ve worked a little bit with their campaign on criminal justice issues, talking about some of the things that we’ve talked about here, how important it is that inside of prisons we do more to provide vocational and educational training in order to give people the skills they need to succeed when they come out. And O’Malley made that a big part of his criminal justice reform platform.

AMY GOODMAN: How did they end up reaching out to you? Or did you reach out to them?

JEFF SMITH: My ex-girlfriend of many years is his deputy campaign manager, and we’ve—even though we’re no longer together, we have a lot of similar political and policy views. And so, she’s helped keep me engaged. And I’ve actually known the governor since he was—since he was first elected governor.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to President Obama speaking after meeting in July with six nonviolent drug offenders during his unprecedented presidential visit to the El Reno Federal Correctional Institution in Oklahoma.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: Visiting with these six individuals, and I’ve said this before, when they describe their youth and their childhood, these are—these are young people who made mistakes that aren’t that different than the mistakes I made and the mistakes that a lot of you guys made. The difference is, they did not have the kinds of support structures, the second chances, the resources that would allow them to survive those mistakes.

AMY GOODMAN: So that’s President Obama speaking after being at the El Reno Federal Correctional Institution in Oklahoma. The significance of what he’s saying, and also making a clear distinction between violent and nonviolent criminals, what you think about that, Jeff Smith?

JEFF SMITH: Well, what he’s saying is significant. And he’s taken some good steps, along with Attorney General Holder, to direct that U.S. attorneys around the country not necessarily go after drug offenders in this harsh a way. But his delineation between nonviolent and violent prisoners is a little bit disingenuous, frankly, because if we don’t deal with violent offenders and we just think, oh, we can solve the problem and decarcerate in the country by looking at nonviolent offenders, we’re kidding ourselves, right? Most—the federal system has a couple hundred thousand people, but there’s 2.3 million people that are behind bars in this country. So most people in this country are in state prisons. And about half of all people in state prisons are violent offenders. And so, if we don’t do something to ease sentences on violent offenders—and keep in mind, a violent offender could be someone who when they were 19 committed an armed robbery, and now they’re 49 years old. Right? It could be 30 years later. They could have had 30 years of exemplary behavior in prison, but they’re still considered, you know, a violent offender and someone who may be a subject of “three strikes and you’re out,” and so they have a life sentence for things that they did 20 years ago.

AMY GOODMAN: Jeff, talk about what would most help someone coming out of prison not to return.

JEFF SMITH: The number one thing that would help people coming out of prison is employment. And having a system where 90 percent of employers are using background checks, which in this day and age are done, you know, cheaply and very quickly, is a problem, because the majority of employers in this country tell—in surveys, tell people that they would not hire someone with a record. So the first thing we need to do is have Ban the Box legislation around the country, so that no employer can discriminate against people with a criminal record.

Second thing we need to do is the family support side and the community support side. A lot of people who have been locked up, that I was locked up with, have been locked up for 15 years or longer. All the people that they knew and loved have fallen by the wayside. That’s a long time to ride with someone who’s incarcerated. Right? And so, they don’t have anyone to come home to. They don’t—they need help. They need people to tutor them. They need connections. They need job referrals. They need people to vouch for them, and people who have good reputations in the community to say, “Hey, this guy will do a good job for you.” And that means all of us. It’s incumbent upon all of us to get to know people who have been incarcerated, and try to help ease that very difficult transition, when they face discrimination in housing, employment, education, public assistance—in so many different realms—and make their life a little bit easier.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you find it a problem, getting out of prison, getting a job? You end up being a professor here at The New School, and you have a record. Did it come into play at all?

JEFF SMITH: Of course it came into play. I remember seeing the vice provost at a cocktail reception my second day at The New School. And I took her aside, and I said, “I just want to thank you. I’m not sure if this rose to your level, but I have kind of a unique background.” And she looked at me, and she said, “You’re not sure it rose. Well, of course it rose to my level. It had to go to the very top to hire someone who did something as stupid as what you did.” She’s like, “You’re pretty lucky.” I said, “I know I’m lucky.” Because most people with a record wouldn’t have the opportunities that I’m blessed with, frankly, coming out. And most of the people that I was locked up with don’t have any of the advantages I had.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve got this picture on the back of your book—I’ve got it here—and it’s below the recommendations of people like Bryan Stevenson, who’s the great criminal justice advocate in Alabama. It’s a picture of the people who you worked with in the prison warehouse. There are six other people besides you, in the middle. How many of them are out now?

JEFF SMITH: One of them is definitely out now. There’s a second that’s close. But they all had much longer sentences than I did. As my celly said when I first got there—

AMY GOODMAN: “Celly” being your cellmate.

JEFF SMITH: My cellmate. He asked me—yeah, they call them your bunky or your celly. He said, “How much time you got?” I said, “A year and a day.” He said, “Man, I’ve done more time in this place on the toilet than you’ve got time.” He’d been locked up, in and out of prison, for about 25 years at that point, on a variety of charges. And that’s the reality for most of these guys.

AMY GOODMAN: So, many people who are in your position after you got out, you would not like to make a big deal, you’d like to forget it, you would like to sweep it under the carpet, not let people know about your past. Instead, you are on the board of a nonprofit called the Prison Entrepreneurship Program, or PEP. Explain what this is.

JEFF SMITH: PEP is this amazing organization that works inside of prisons in Texas to train inmates in how to craft full-length business plans, and also gives them broader life coaching about how to turn around their life when they get out. They’ve got visiting executives from all over the world coming in to mentor guys in prison, and MBA students from all over the country.

AMY GOODMAN: Are they mentoring guys in prison or—

JEFF SMITH: In prison.

AMY GOODMAN: —people who are out of prison?

JEFF SMITH: Guys who are in prison. OK? And this is a—Rick Perry knows all about this and has blessed it in a state prison. So it’s, you know, pretty good news. And the recidivism rate for graduates of the PEP program over the last 11 years is just 6.5 percent, one-tenth of the national recidivism rate. So, not only are they not recidivating, but several graduates of the program have actually started multimillion-dollar businesses. So, goes back to our point about their entrepreneurial potential inside of prison.

AMY GOODMAN: So explain exactly what they’re doing. What is the plan for these people? They come up with a business plan?

JEFF SMITH: They don’t—I mean, they come up with an idea. And then experienced executives, professors and MBA students advise them on the different components of how to put together a full-length business plan.

AMY GOODMAN: And they have to present these plans?

JEFF SMITH: And then they go through—they actually present these plans about 120 different times. They hone their pitch that many different times, in small groups, before they give it to the large group at the end.

AMY GOODMAN: Like, kind of like a Shark Tank situation.

JEFF SMITH: Exactly like Shark Tank, yeah. And I’m actually—I’m on the board of another organization—it’s actually a company—called American Prison Data Systems, which is working to put a tablet computer, fully equipped with vocational training software and education software, in the hands of every prisoner in the country. So, I promised the guys that I did time with that I wasn’t going to forget about them or the things that were important to people incarcerated all over the country, and that’s why I’ve chosen to pursue some of this stuff since coming out.

AMY GOODMAN: You said that some people are now starting multimillion-dollar businesses. Like what?

JEFF SMITH: Like automotive repair, like landscaping, like—one of the most successful is a Houston janitorial business, which has contracts with some of the largest skyscrapers in Houston. So, there’s a lot of different examples. There’s a guy doing a personal fitness business. There’s a health food vending machine business. There’s a bunch of different types.

AMY GOODMAN: So how do you get people to volunteer to help these prisoners inside prison and once they get out, given the stigma and the legislation around the country, the laws that are in place that have so—have kept prisoners down for so long, everything like the whole having to say that you were in prison when you’re asked that by a judge—when you’re asked that by a potential employer, though that is being challenged around the country?

JEFF SMITH: Well, I’ll give you a broad way and then a specific way. Broadly speaking, we try to first work with people who have a relative in prison. Right? Because those people tend to be much more sympathetic to the cause. You know, right now there’s millions and millions of Americans that have a relative who’s locked up. So, you don’t always know it. Most people don’t talk about that member of the family; that’s like a black sheep, and so they hide it from people. But we’re trying to get people to be more open about it, in the same way that the LGBT rights movement benefited over the course of the last several decades by getting people to be open and come out of the closet.

More specifically, there’s a clever little thing that PEP does, which is, they’ve got little cards that the staff and volunteers have. Instead of get-out-of-jail-free cards, they’re called get-into-jail-free cards. And once you come in the jail with this program and see the transformation going on and how positive these prisoners are looking at life on the outside and their own potential to thrive, it’s hard to not be involved.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to end where I ended the first part of the interview, and that’s in Ferguson. You’re a Missouri politician. You were a state senator, before you went to jail and before you moved to New York to be a professor. Talk about what’s happening now, a year after Michael Brown was killed by police, and the protests highlighting not only police brutality, but the—how police take advantage of the poor in this community.

JEFF SMITH: So, I’d say it’s been one step forward, sometimes one or two steps back, in Ferguson and in St. Louis over the last year. We’re still seeing a lot of protests. There have been several more police-involved shootings in the past year. The municipal courts, that The Huffington Post and Radley Balko and I described, in Ferguson in Black and White, that have caught so many young people up in the system, are still mostly operating as they had before. There are some small reforms around the edges. As you noted, Ferguson has taken off warrants on people and given sort of a blanket amnesty, and the city of St. Louis itself has done that, as well. But—

AMY GOODMAN: And like 10,000 warrants cleared. I want to go to Lesley McSpadden, Mike Brown’s mother.

JEFF SMITH: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: I bumped into her in Selma, Alabama, on the 50th anniversary of the march from Selma to Montgomery that John Lewis led, had his head bashed in, for voting rights. And I asked her about what should happen back in Ferguson.

AMY GOODMAN: And what do you think will happen now? Do you want there to be monitoring, federal monitoring, of Ferguson police?

LESLEY McSPADDEN: Being honest, I don’t think there should be a Ferguson Police Department anymore.

AMY GOODMAN: What should there be?

LESLEY McSPADDEN: The police department should be disbarred and maybe took over by a more—you know, a better set of people, maybe even just fire them all and just hire in some new cops. And with this new training that you’re giving to an old cop, just start fresh with a new batch, and they’ll get the proper training that you’re saying you failed to give the cops that are already working.

AMY GOODMAN: So that’s Lesley McSpadden, Michael Brown’s mother, and she said the police department should be—

JEFF SMITH: Disbanded.

AMY GOODMAN: —disbanded.

JEFF SMITH: It should be disbanded. And I—

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain. How would it be disbanded?

JEFF SMITH: It would be disbanded by essentially forcing Ferguson—and not just Ferguson, but there’s 90 municipalities in St. Louis County. Eighty-one of them, you know, have their own traffic courts and police systems. And it’s ridiculous to have 90 municipalities in a county of a million people. There’s so much duplication. There’s—you know, it’s really expensive to have police and fire trucks, that whole public safety apparatus. So, we should probably disband a lot of the police and fire departments up in that part of St. Louis County.

AMY GOODMAN: Why do these little ones lead to so much corruption?

JEFF SMITH: Because the towns have lost most of their tax base. Shopping—as whites have fleed or flown out of North St. Louis County—

AMY GOODMAN: Fled.

JEFF SMITH: Fled—thank you, Amy. Shopping malls have left. All types of businesses have left. Declining tax bases, struggling school systems. Properties that you could have bought for $100,000 40 years ago, you might be able to buy for $40,000 or $50,000 today in some of these towns, whereas in the more affluent parts of St. Louis, properties that you could have bought for $100,000 30 years ago are now $800,000 or $900,000. So you’ve got declining revenue bases, and these small towns are forced to go somewhere to try to sustain themselves. And the place they’ve gone are traffic tickets, occupancy permit violations, violations for not having your grass, you know, cut, for having peeling paint off your shutters. They’re really—you know, it’s like debtors’ prison, because they’re taking people who are too poor to maybe maintain a house or keep their driver’s license current, and then they’re locking them in prison and making it so that those people have a criminal record that stains them for the rest of their life.

AMY GOODMAN: And then the town apparatus is sustained. Explain the documentary evidence you have of this.

JEFF SMITH: Well, there’s a letter coming from the Ferguson, I guess, interim city manager last December—this is four months after the Mike Brown situation—saying that because of increased security costs, Ferguson was looking at, this fiscal year, running a $1.5 million shortfall. How will they make up that shortfall? The advice from the city manager was: “We need to give more traffic tickets.” So, clearly there’s places that have not learned the lessons that we should all be taking away from the last year.

AMY GOODMAN: Jeff Smith, I want to thank you for being with us. Jeff Smith, author of the new book, Mr. Smith Goes to Prison: What My Year Behind Bars Taught Me About America’s Prison Crisis. He’s a former Missouri state senator, now a professor at The New School here in New York. He’s also on the board of the nonprofit group, Prison Entrepreneurship Program, or PEP. And he’s the author of the e-book, Ferguson in Black and White. This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options