Topics

The legendary media activist Everett Parker died Thursday at the age of 102. In the 1960s he led an effort to have the license of a Jackson, Miss., TV station revoked for attempting to squelch the voices of the civil rights movement. At the time, Parker was director of communications of the United Church of Christ. Parker filed a “petition to deny renewal” with the FCC, initiating a process that eventually got the station’s license revoked by a federal court and had far-reaching consequences in American broadcasting.

“Much of the successful activism today related to Internet openness and media consolidation traces back to Dr. Parker’s work in the 1950s and 1960s,” noted Earl Williams of the United Church of Christ.

When Parker retired in 1983, Broadcasting Magazine described him as “the founder of the citizen movement in broadcasting.”

According to the Museum of Broadcast Communications,

The work of Parker and the Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ took an important turn in the 1960s, as the civil rights movement was gaining momentum. After reviewing the civil rights performance of television stations in the South, the Office identified WLBT-TV in Jackson, Mississippi as a frequent target of public complaints and Federal Communication Commission (FCC) reprimands regarding its public service. In 1963, the Office filed a “petition to deny renewal” with the FCC, initiating a process that had far-reaching consequences in U.S. broadcasting. The FCC’s initial response to the petition was to rule that neither the United Church of Christ nor local citizens had legal “standing” to participate in its renewal proceedings. The UCC appealed, and in 1966, Warren Burger, then a Federal appeals court judge, granted such standing to the UCC and to citizens in general. After a hearing, the FCC renewed WLBT’s license, resulting in another appeal by the UCC. Burger declared the FCC’s record “beyond repair” and revoked WLBT’s license in 1969.

Based on this new right to participate in license proceedings, Parker’s office began to work with other reform and citizens’ groups to monitor broadcast performance on a number of issues, including employment discrimination and fairness. In 1967, the Office’s petition to the FCC dealing with employment issues lead to the Commission’s adoption of Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) rules for broadcasting. In 1968, it participated as a “friend of the court” in the landmark Red Lion case, which confirmed and expanded the Fairness Doctrine.

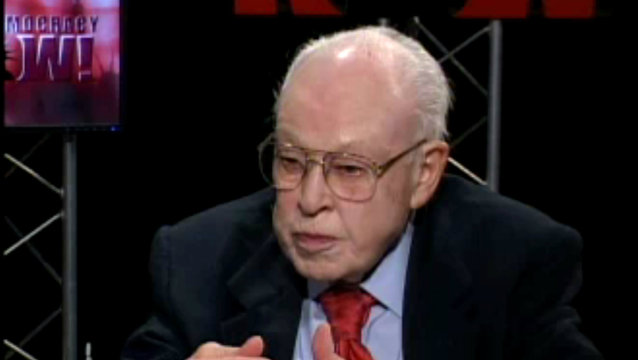

In 2008, Everett Parker appeared on Democracy Now!

TRANSCRIPT

JUAN GONZALEZ: We take a look now at the only time a television station had its license revoked for failing to serve the public interest. It was in the 1960s in Jackson, Mississippi. TV station WLBT had its license revoked for attempting to squelch the voices of the civil rights movement of the time.

The station first came under scrutiny by the Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ. The Office was founded and headed up by media activist Everett Parker. He identified WLBT as a frequent target of public complaints and FCC reprimands regarding its public service. Parker filed a “petition to deny renewal” with the FCC, initiating a process that eventually got the station’s license revoked by a federal court and had far-reaching consequences in American broadcasting.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Everett Parker joins us now in our firehouse studio. He has been a media activist for more than six decades, currently an adjunct professor of communications at Fordham University. He’s ninety-five years old. Welcome to Democracy Now!

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Your age is important because you bring us back to a key time. Dr. King, in his early years, came to New York, and he had a meeting with a group of people, including Andrew Young and those close to you, to talk about his concern about how the civil rights movement was being portrayed in the Southern media.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: That’s correct. He did. He had a luncheon with Truman Douglass, who was then the head of the Board of Home Missions of the Congregational Christian Churches. The Congregational Churches united later with the Evangelical and Reformed Church fifty years ago to form the United Church of Christ, which is what we have now. But at that time, the Congregationalists were very much interested in the civil rights movement, and Dr. King did complain to Truman Douglass about how they were treated on television, although he got a break down there when they turned the dogs loose, but that was not a planned thing.

So, as a consequence of his talking to Andy Young, who then was a young minister whom we had down there training people — he trained Louise Hamer —-

AMY GOODMAN: Fannie Lou Hamer.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Yes. And I went down, and I really looked at stations throughout the -— from New Orleans to the East Coast and found that it was a very bad situation. And I had earlier — teaching at Yale Divinity School, I had developed a new way of monitoring television stations. The FCC has a system of saying, “Send us your record for Monday of a certain date, Tuesday of a certain date, and so forth.” I developed a way of monitoring a station from the time it signed on to the time it signed off. And the FCC accepted that as coequal with its method.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Dr. Parker, one of the things in relation to the previous segment we just had on the situation with former Governor Siegelman was that this Alabama station suddenly stopped carrying a national program. You found the same situation —-

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Oh, yes.

JUAN GONZALEZ: —- occurring in Jackson, Mississippi, where the local NBC affiliate there suddenly, when Thurgood Marshall would get on the air or somebody from the NAACP on a network broadcast, they’d suddenly interrupt the program and not run it in their local area.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Well, when Marshall won Brown v. Board of Education and was on NBC, yes, they put up a sign — “Sorry, cable trouble” — and blamed it on the telephone company. But anyway, I hit on WLBT, simply because of the terrible things that it was doing. The mayor of Jackson at that time had a tank. He had had a tank built to protect him from —- he said “from the n———s” and —-

AMY GOODMAN: A tank?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: A tank.

AMY GOODMAN: Like a military tank?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Well, not really a military tank, but a tank. It was a white thing that he got into, and he’d broadcast from that. And every day he would come on the air, and he would urge people especially to attack our American Missionary Association college, which was just across the street from the city line of Jackson. And that was one thing that they did. There had never been a program on WLBT that had blacks, unless they were arrested. They didn’t use courtesy titles with blacks.

AMY GOODMAN: Like “Mr.” or “Mrs.”

DR. EVERETT PARKER: “Mr.” and “Mrs.,” and -—

JUAN GONZALEZ: And they also didn’t employ any African Americans, although I think the listening area was about 50 percent African American?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: It was 42 percent, yes. And the other thing that they did, they had only two churches in town that had ever been on the station, and they were churches that Fred Beard, the manager, belonged to and one other church. So this was a station that did everything the wrong way.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Dr. Parker, you did something very interesting. You used students —- only white students, is that right?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: No.

AMY GOODMAN: —- who monitored the station every hour.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: No.

AMY GOODMAN: No?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: The people that did this were not students. They were citizens of the community. One family loaned its house, because they had a huge porch area, a glassed-in porch. I trained the monitors. But I very carefully was not introduced to any one of them. And so, when the time came that I had to testify, I said I didn’t know any of them, and I didn’t, so I never named one, which was very important down there, because years, years later, the good old boys identified the family, because they remembered all the television sets that had been taken into the house, and they drove that family out of Jackson.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Of course, and these were the days of the Sovereignty Commission in Mississippi, where basically the government was surveilling and going after anybody who was involved in the civil rights movement, wasn’t it?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: That’s correct. But here in Jackson, of course, Medgar Evers had just been murdered, and it was a very tense situation. A minister, a Methodist minister, black, Robert L.T. Smith, had wanted to run for Congress, and they would not sell him time. He wasn’t asking for free time. Mrs. Roosevelt got after the White House, and they didn’t order, but they sent a word down that the White House would like to see him have the time sold to him. He put the program on, and Fred Beard, the manager of the station, took Dr. Smith outside and walked him along the river, because the station’s right on the river. He said, “I’m going to be so sorry when I see your body floating down the river tomorrow.”

AMY GOODMAN: So you appealed — applied to the FCC. You wanted their license revoked, that they weren’t serving the community. But the FCC did not side with your appeal.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: No. What we asked the FCC to do was to hold a hearing on the renewal of the license and to hold a hearing in Jackson, Mississippi. And they refused. And so, there wasn’t much you could do about it, because the public had no standing at that time. But we appealed the FCC decision.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And when you say — by “standing,” just for our listeners and viewers, you’re saying that, according to regulatory law, the FCC did not recognize that the public in general had an interest, a direct interest —-

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Yes.

JUAN GONZALEZ: —- in a station, only somebody else who was trying to — who had an economic interest in getting the license or competing with them could have the standing to challenge that license, right?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Yeah. If you and I had a contract and I had — I said you didn’t fulfill the contract and I went to court, I would have to prove to the court that I had a right to sue you, and the court would give me standing — that’s the legal term — to sue. And the public had no right, if — and we were told off very quickly by the FCC. But we tried some other things beforehand, but I won’t go into all the things we did.

AMY GOODMAN: So, ultimately, you had to go to court. You couldn’t get the FCC to deny renewal of the license.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: No. So we — I talked to Orrin Judd, who was the lawyer for the Church and a very distinguished attorney in New York. And he said, “Well, you know, everybody likes to make new law.” And so, we filed a suit. But they hired Paul Porter, former chairman of the FCC, to defend them. And Mr. Judd, being the gentleman that he was, we went down to Washington to talk to Porter before we did anything more. And he kind of threatened us. He said, “If you do this” — he and I knew each other. He said, “If you do this ever, I will carry this out year after year, and I will bankrupt the United Church —- the Congregational Churches.” And I said, “Paul, if this goes on year in and year out, and you die and I die, the Church will still be in there.” And the terrible thing was that he did die. He choked to death in a restaurant. And -—

AMY GOODMAN: And it was Judge Burger, who then was a federal appeals court judge, who ultimately ruled on your behalf?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Burger was the chairman of the panel, yeah. And to make a long story short, we asked for a hearing, and the court ordered the FCC to have a hearing on the renewal of the license in Jackson. Now, that hearing was done before a — at the time, they were not called “judges,” but now they’re called “judges.” The FCC has a law division that handles things like this.

AMY GOODMAN: How did they ultimately get their — we only have about a minute, so I wanted to ask: how did they ultimately get their license revoked by the court and not the FCC?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: No, the FCC —- after the hearing in Jackson, which lasted for weeks, the FCC voted five-to-two to renew the license for a year, knowing that they’d come back at the end of the year and say, “We’ve done all the things you want us to do.” And the two that voted against this, Nick Johnson and another member of the FCC, they said in their vote that if you wanted to get a license of a station revoked, you’d have to go in and steal it at night. And -—

AMY GOODMAN: But the license was revoked?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Yeah.

JUAN GONZALEZ: The court eventually — it was a thirteen-year battle, but the court eventually, again, ordered the license —-

DR. EVERETT PARKER: No, they had the hearing. The FCC then voted again, five-to-two, to renew the license for a year. And at that point, Judge Burger, on the morning of the day that he was sworn in as Chief Justice of the United States, he filed the opinion, the decision. And the decision was that the license was revoked.

AMY GOODMAN: And ultimately, Medgar Evers, soon after, great civil rights leader who was soon assassinated, went on the air on this station that had not heard black—- or broadcast black voices.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Well, the station, during this long period of years — it was thirteen years before a license was issued. During this period, a group of public people, Aaron Henry being the leader of that — Henry was the one that was willing to sign the petition with me so we could go to court. And he was, at that time, chairman of the NAACP. This group ran the station.

AMY GOODMAN: They took over the station.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Yeah, and they did such things as they put —-

AMY GOODMAN: Medgar Evers?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: No, not Medgar Evers. The CBS -—

AMY GOODMAN: Randall Pinkston?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: Randall Pinkston. [inaudible]

AMY GOODMAN: He became an anchor, right?

DR. EVERETT PARKER: My memory for names is terrible. Pinkston was just a young man, and it was a terrible chance that he was taking to come on the air and do the news. And in a few weeks, he was the most popular news program on the air.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Dr. Parker, we want to thank you very much for being with us. On Dr. Parker’s retirement in 1983, Broadcasting Magazine hailed him as “the founder of the citizen movement in broadcasting” who spent “some two decades irritating and worrying the broadcast establishment.”

DR. EVERETT PARKER: That’s true.

AMY GOODMAN: Thanks so much for being with us.

DR. EVERETT PARKER: I’m still doing it.

AMY GOODMAN: Thank you for taking that history into the present.