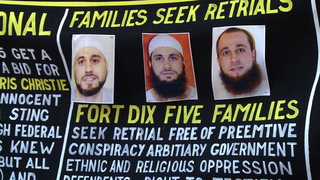

In 2008, five Muslim men from suburban New Jersey were convicted of conspiring to kill U.S. soldiers at the Fort Dix Army base. The men say they were entrapped by the FBI. Three of the men were brothers—Shain, Dritan and Eljvir Duka. They are now serving life sentences. On Wednesday, they appeared in court for a rare hearing. In this web exclusive, we air a portion of a short documentary produced by The Intercept and speak to Bob Boyle, attorney for Shain Duka.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. On Wednesday, three brothers convicted in the case of the Fort Dix Five appeared in a courthouse in Camden, New Jersey, for a rare court-ordered hearing to determine whether they received a fair trial and effective representation from their lawyers. In 2008, the brothers—Shain, Dritan and Eljvir Duka—were among five men from suburban New Jersey who were convicted of conspiring to kill U.S. soldiers at the Fort Dix Army base. The three are serving life sentences, but their supporters say the men were entrapped by the FBI. Last year, The Intercept released a short video on the Fort Dix Five case. The video begins with then-U.S. Attorney Chris Christie speaking in 2007 from the steps of the federal courthouse in Camden, New Jersey.

CHRIS CHRISTIE: The philosophy that supports and encourages jihad around the world against Americans came to live here in New Jersey and threaten the lives of our citizens through these defendants. Fortunately, law enforcement in New Jersey was here to stop them.

BURIM DUKA: My oldest brother is Dritan Duka. The second oldest is Shain Duka. The third oldest is Eljvir. My three brothers and two other defendants got arrested for conspiracy to attack a military base here in New Jersey, the Fort Dix military base. We used to go out in the wintertime, when—because we owned a roofing company, we couldn’t work wintertime, when it was snowing, so we would go on a vacation with just us guys.

UNIDENTIFIED: There he is! He’s coming!

UNIDENTIFIED: Here comes Shain, right there! Look at him! Yo, this is nice! Oh, it’s a nice view.

BURIM DUKA: We were recording, of course, so that everybody could have a little clip of what we did when we were in the Poconos.

UNIDENTIFIED: I’ll record. Want me to record? Allahu Akbar.

BURIM DUKA: And then, me and my brother, Suleiman, we went to Circuit City to transfer the cassette that we had into a DVD for each person that went to the Poconos with us, so they could have one.

UNIDENTIFIED: We’re at the range for the second time, going to try to shoot some more. This is what we did yesterday.

UNIDENTIFIED: Hey, throw something up for me. Throw a snowball up for me.

UNIDENTIFIED: Allahu Akbar.

UNIDENTIFIED: Man, this thing is fantastic!

BURIM DUKA: The Circuit City person turned in the video to the police and said, “These people are shouting out, 'Allahu Akbar!'”—which means “God is great”—”while shooting weapons.” Then the FBI started investigating us from that day on. They got two informants involved—Mahmoud Omar, an Egyptian guy, and Besnik Bakalli, who was an Albanian informant. He was mainly here for us Duka brothers. Bakalli, because we stood with him more, he would always try to bring up topics about like politics, about what was going on in the news, was always trying to bring up jihad, why are we not doing nothing, how come we’re not overseas. Older people and women are doing stuff, and we’re not. He would always try to get on our bad side, but we always played it cool.

BESNIK BAKALLI: You learn the Qur’an. You’re going by Qur’an. And you’re going to—you’re not fighting for Muslims. You’re still questioning yourself. Why you’re not fighting for Muslims?

ELJVIR DUKA: Oh, Besnik.

TONY DUKA: Because we have nothing to do with that.

UNIDENTIFIED: We don’t—well, we don’t have the balls to go and die.

BESNIK BAKALLI: Don’t question yourself.

SHAIN DUKA: Oh, Besnik!

BESNIK BAKALLI: That’s what I’m saying.

SHAIN DUKA: I will tell you straight up: We don’t have the balls to do that.

BESNIK BAKALLI: No, don’t say that, because when our elders have gone to fight, how can we just sit at watch?

SHAIN DUKA: We don’t have the balls. We’re not gonna do nothing.

UNIDENTIFIED: We’re talking—we’re talking about certain death. You put bombs on your body, and you hit ’em up.

SHAIN DUKA: No, that I wouldn’t do. That I wouldn’t do. I’d rather go out—

UNIDENTIFIED: It’s up—it’s up to you.

SHAIN DUKA: I cannot do that.

BESNIK BAKALLI: Yo, if you guarantee me I go to heaven, I do it. Would you guarantee me that?

SHAIN DUKA: No.

BURIM DUKA: The informant, Omar, hung out with our friend, Shnewer. Shnewer wasn’t like my brothers. He said all types of crazy things. And together, the informant and Shnewer came up with a plot to attack Fort Dix. The informant needed Shnewer to say that my brothers were in on the plot. But once the government seen that my brothers weren’t in and knew nothing about it, they created an illegal gun deal. Mahmoud Omar knew that my brothers were into guns. He spent a lot of time with us. He set up the deal for my brothers to buy some weapons, and the weapons were provided by the FBI.

TONY DUKA: This is an M-15.

MAHMOUD OMAR: What is the difference between 16 and 15?

TONY DUKA: Sixteen is more powerful.

MAHMOUD OMAR: Sixteen is more power?

TONY DUKA: Sixteen is what the military uses. What’s that?

SHAIN DUKA: It’s an ambulance.

POLICE OFFICER: Police! Get down! Get down! Get down! Get down!

BURIM DUKA: And then, when we pulled up, we seen a whole bunch of feds up by my brother’s apartment complex.

AMY GOODMAN: Fort Dix Five, produced by The Intercept. On Wednesday, the three brothers made a rare court appearance in Camden, New Jersey. For more, we’re joined by one of their attorneys, Bob Boyle. He’s the attorney for Shain Duka, one of the three defendants in the Fort Dix Five case.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!

ROBERT BOYLE: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: As we continue our discussion, explain where the Duka brothers are. They’re all separate right now, held in three separate prisons, all sentenced to life without parole.

ROBERT BOYLE: Yes, they’re all in three maximum-security prisons. Eljvir is under the most harsh conditions. He’s in the supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, which is basically a 24/7 solitary confinement prison. Dritan Duka is in a maximum-security prison in West Virginia. And Shain Duka, my client, is in a maximum-security prison in Kentucky.

AMY GOODMAN: So the judge in this case, who was the judge in the original case, agreed to hold this hearing. Why?

ROBERT BOYLE: Because part of our claim is that they, all three brothers, wanted to testify at their trial to tell their side of the story, but that their lawyers coerced them into giving up their right to testify by telling them, “We’re not prepared to put you on the stand.” And they each submitted affidavits setting forth these claims. The lawyers submitted affidavits for the government, cooperated with the government, saying, “We did not tell them this.” And so, the judge, by law, had to hold an evidentiary hearing. It’s a rare thing on a motion to vacate a conviction, particularly in a terrorism case, to get this kind of an opening. And so, what happened in Camden yesterday was that the three Duka brothers testified, and their lawyers testified, and now the—

AMY GOODMAN: In a sense, their lawyers are testifying against them.

ROBERT BOYLE: Absolutely. They’re testifying for the government. Their defense lawyers, who were their advocates, are testifying for the government. And the same judge who gave them life without parole will be issuing the decision.

AMY GOODMAN: So you’re the appeals attorney for one of the Duka brothers. And what are you hoping will come out of this hearing, that will—the judge will make his decision in mid-March.

ROBERT BOYLE: Well, what we’re hoping is that the judge will find in our favor on the factual issue that they were in fact denied their right to testify. Then there will be a further proceeding where we will have to prove that had they testified at trial, the result would have been different. And that will be a significant victory if we get that far.

AMY GOODMAN: What would Shain Duka say, your client?

ROBERT BOYLE: Well, that they would—he said a lot of it yesterday, even though he wasn’t supposed to, that they were not part of any plot. They knew of no plot. Did they have theoretical and religious discussions about Islam, the role of the U.S.? Yes, they did. Did they do target practice in the woods? Yes, they did—just like the militia in Oregon. But they were never part of any plot to do anything, and, in fact, had plans to expand their business, to legalize their immigration status and to raise—

AMY GOODMAN: They’re Albanian Muslims?

ROBERT BOYLE: They’re Albanian Muslims who came here as children, who were never documented. And we were able to show that they had actually, shortly before their arrest, retained a lawyer in order to legalize their immigration status—something totally inconsistent with the theory that they were going to do anything illegal.

AMY GOODMAN: But they were convicted. Talk about the Fort Dix piece, then contention that they were planning to attack the soldiers at Fort Dix.

ROBERT BOYLE: Well, this is the nature of conspiracy laws and the evidentiary rules. In federal court, a co-conspirator’s statement—an alleged co-conspirator’s statement is admissible and can provide the basis for conviction. So you had the government informant speaking to a man by the name of Mohamad Shnewer. Mohamad Shnewer told the government informant, in a secretly recorded conversation, “Oh, yeah, the Duka brothers know all about this.” But there was no proof—in fact, the government conceded at trial that there was no proof that the Dukas themselves ever said they knew about anything. On that basis, they were convicted.

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, the informant, right, Mahmoud Omar, said he didn’t believe the Duka brothers were guilty, that they knew.

ROBERT BOYLE: At some point in the trial, it came out in a recorded conversation. He’s talking to Mohamad Shnewer, and he says to him, “Mohamad, do they really know about what’s going on?” And Mohamed says, “Oh, yeah, of course.” But the whole tone of the conversation was that even the government informant had questions about whether the Duka brothers were doing anything.

AMY GOODMAN: And this all came from the Duka brothers themselves bringing in their film of their target practice out in the woods to Circuit City, and Circuit City employees looking and seeing the film and being afraid and giving it to the government?

ROBERT BOYLE: Yes, that’s the way it happened. They did a weekend in the Poconos. That—they did do target practice, but they also did skiing, horseback riding and a lot of things that young men in their twenties would do, and on occasion said “Allahu Akbar” or similar phrases, “Inshallah.” And some people at Circuit City, frightened by this, turned it over to the FBI.

AMY GOODMAN: Chris Christie made his name on this as U.S. attorney, as the prosecutor in this case. Can you talk about the significance of this? Now, of course, the presidential candidate.

ROBERT BOYLE: Well, I mean, I think it creates some opportunities, and it creates some difficulties. I think it creates some difficulties that the judge, who is going to rule, knows that this is the case that Chris Christie made his name on. And while—

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, he is the sitting governor of New Jersey, Chris Christie.

ROBERT BOYLE: Yes, and while that’s not supposed to make a difference, we know that these kind of things make a difference. But it also, because of the notoriety of the case and him talking about it all the time, it creates an opportunity for the public—and, hopefully, unbiased media—to take another look at it. What really happened here? Really, what happened here was nothing. Nothing happened.

AMY GOODMAN: How isolated is this case? How unusual is this case?

ROBERT BOYLE: Well, it’s usual, unfortunately, in many ways, because we had the case here in New York of the Newburgh Four, another case where—which was entirely concocted by law enforcement, an alleged plot—and with similar results. These men are serving long terms in prison. So, sadly, it’s very usual. It’s unusual to the extent that we were able to get an evidentiary hearing and have our—now, our foot in the door to be able to show that this was a unjust conviction. And so, we’re hoping that this hearing that happened yesterday will lead to further proceedings in this case.

AMY GOODMAN: From The Intercept last year, they said, of 508 defendants prosecuted in federal terrorism-related cases in the decade after 9/11, 243—about half—were involved with an FBI informant, while 158 were the targets of sting operations. Of those cases, an informant or FBI undercover operative led 49 defendants in their terrorism plots.

ROBERT BOYLE: You know, that’s the—that’s been the MO since, unfortunately, from 9/11—not that this hasn’t happened before then—but the seizing upon people, who are perceived by the government to maybe be a threat, to make certain statements, be they political or religious, and then, essentially, create crimes or create alleged crimes.

AMY GOODMAN: Eljvir seemed very confused at the hearing, one of the three Duka brothers. He’s the one being held in supermax in Florence, in Colorado, is that right?

ROBERT BOYLE: Thats’ right.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking about isolation—for how long he’s in solitary confinement?

ROBERT BOYLE: Well, he’s been now in—been in solitary for over seven years. And, well, he reacted—he appeared confused, but he reacted in court like many people do who have been in solitary confinement. You’re alone 24/7. You have no stimulation. You walk into court. There’s a hundred people there. There’s a judge. There’s lawyers. There’s court reporters. You’re not—

AMY GOODMAN: There’s his family, who he hasn’t seen in all of these—

ROBERT BOYLE: His family.

AMY GOODMAN: His brothers.

ROBERT BOYLE: And his brothers. And you’re bombarded by this stimulation. And we know, from a lot of the studies, that fortunately have come out in the last few years, the effect of even what a few weeks of solitary can do on your psyche. This man has been essentially in solitary for seven years. And so, yes, he reacted as one would expect.

AMY GOODMAN: So, what you’re hoping to come out of this case in March?

ROBERT BOYLE: Well, we’re hoping that the court rules in our favor on the narrow factual issue as to whether they were unconstitutionally deprived of their right to testify. If the court rules favorably on that, we’ll have another hearing where they will, in more detail, describe what they would have said had they testified at trial. If we prevail on that part of it, we’ll get a new trial.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Bob Boyle, we’ll continue to follow this case. Bob Boyle, attorney for Shain Duka, one of the defendants in the Fort Dix Five case. This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options