Topics

Guests

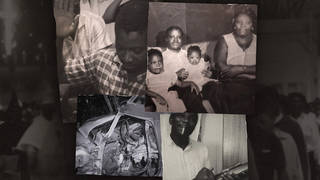

- Robert Kingformer member of the Black Panther Party who spent 32 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola Prison—29 of them in solitary confinement. He was released in 2001 after his conviction was overturned.

- Albert Woodfoxlongest-standing solitary confinement prisoner in the United States. As a member of the Angola Three, he was held in isolation in a six-by-nine-foot cell almost continuously for 43 years.

- Sekou Odingaformer Black Panther who was a political prisoner for 33 years and was released in November 2014.

- Marshall "Eddie" Conwayformer Baltimore Black Panther leader who was released from prison in 2014 after serving 44 years for a murder he denies committing.

Watch the complete roundtable discussion on the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party with four former Panthers who spent decades behind bars as political prisoners.

In New York, in his first global broadcast interview, we’re joined by Sekou Odinga, who helped build a Black Panther chapter in the Bronx. He was later involved in the Black Liberation Army. He was convicted in 1984 of charges related to his alleged involvement in the escape of Assata Shakur from prison and a Brink’s armored car robbery. After serving 33 years in state and federal prison, he was released in November of 2014. In Baltimore, Eddie Conway joins us, a former Black Panther leader who was released from prison in March 2014 after serving 44 years for a murder of a police officer. He always maintained he was set up under the FBI’s COINTELPRO. And in Austin we are joined by two former members of the Angola Three who formed one of the first Black Panther chapters in a prison. Robert King spent 32 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, 29 of them in solitary confinement. He was released in 2001 after his conviction was overturned. With him is Albert Woodfox, who until February of this year was the longest-standing solitary confinement prisoner in the United States. He was held in isolation in a six-by-nine-foot cell almost continuously for 43 years and released on his 69th birthday.

Click here to watch a timeline of Amy Goodman and Juan González interviewing freed Panthers over the past two decades, and learn about the 15 Panthers still in prison.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I’m Juan González. Welcome to all of our listeners and viewers around the country and around the world.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the organization as a way to combat police brutality and oppression. They began in Oakland, where they famously monitored the behavior of the city’s police department, which was notoriously brutal towards African Americans. In 1968, they began a free breakfast program for children. As their efforts drew media attention, the movement grew nationally, and chapters formed in dozens of other cities. Members of the party eventually founded more than 60 different “Serve the People” programs that focused on providing other services, such as free medical clinics. The Black Panthers outlined their goal in a 10-point program that included demands for freedom, land, housing, employment and education.

Around the same time the party was founded, the FBI began a secret program called COINTELPRO to disrupt and, quote, “neutralize” what it characterized as “Black Nationalist Hate Groups.” By 1969, the Black Panthers had become the primary focus of the program, which ultimately led to the deaths and imprisonment of many members and contributed to the party’s collapse.

Well, over the weekend, many former members reunited in Oakland for one of many events marking the group’s 50th anniversary. This came after Beyoncé’s Black Panther-themed performance in February during the Super Bowl halftime show and after PBS aired a major new documentary called Black Panthers: Vanguard of a Revolution. This is the trailer.

JAMAL JOSEPH: The thing that led to the Panthers was what we were seeing on television every day: attack dogs, fire hoses, bombings.

H. RAP BROWN: We stand on the eve of a black revolution, brothers.

ELAINE BROWN: I was a cocktail waitress in a white strip club two years before I joined the Black Panther Party. How did that happen? The rage was in the streets. It was everywhere.

ELDRIDGE CLEAVER: I say that Ronald Reagan is a punk, a sissy and a coward, and I challenge him to a duel.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Eldridge had this incredible ability to encapsulate a thought that stabbed right into the heart of the enemy. Now, was he insane? [bleep] yeah. That boy was crazy!

PAT McKINLEY: They were trying to change government as we know it to terrorist activity.

REPORTER: The State Assembly was in the midst of a heated debate when the young Negroes, armed with loaded rifles, shotguns and pistols, marched into the Capitol.

BEN SILVER: Do you feel the nation is in trouble?

J. EDGAR HOOVER: I think very definitely it is.

BEN SILVER: What is the answer?

J. EDGAR HOOVER: The answer is vigorous law enforcement.

BEN SILVER: How about justice?

J. EDGAR HOOVER: Justice is merely incidental to law and order.

BEVERLY GAGE: The FBI saw the Panthers as a very, very threatening and violent revolutionary movement. They absolutely wanted this organization to be destroyed.

WAYNE PHARR: I felt absolutely free. I was a free Negro. In that little space that I had, I was the king. And that’s what I felt.

WILLIAM CALHOUN: The great strength of the Black Panther Party was its ideals and its youthful vigor and enthusiasm. The great weakness of the party was its ideals and its youthful vigor and its enthusiasm. That sometimes can be very dangerous, especially when you’re up against the United States government.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That’s the trailer for The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, directed by Stanley Nelson. Shortly after the film’s release, Democracy Now! spoke with one of its subjects, Kathleen Cleaver, who served as communications secretary of the Black Panther Party and is now a law professor at Emory University.

KATHLEEN CLEAVER: When I got involved with the Black Panthers, it was a brand new group. And, in fact, there were like five when I got there, because most of them were in Santa Rita prison after the visit to Sacramento. So, it was a new organization. It very, very exciting. And all their principles in the black—it was one of the first organizations based on the concept of black power that had been articulated in Mississippi and by SNCC. And so, I got involved with them. In December, Eldridge and I got married, and I stayed out there and continued to work with the Panthers.

AMY GOODMAN: How did King, Dr. Martin Luther King, fit into this picture?

KATHLEEN CLEAVER: In what way? My picture or the country?

AMY GOODMAN: In your picture, and did he inspire you? How did the Black Panthers relate to him?

KATHLEEN CLEAVER: Oh, everyone was inspired on some level by Martin Luther King. He was a tremendously decent and caring person. He was extremely intelligent, and he inspired a lot of Christians. Now, Eldridge made a comment in one of his speeches in Nashville. He said, “How about integrating some of this bloodshed?” That was one of the issues we had, that it was too much the black people should absorb all the punishment, and we should be forgiving, and we should want to be peaceful in the face of murderous brutality in the middle of the Vietnam War. Well, that wasn’t really a message that a lot of young people cared for. And so, when the Black Panthers came out and started talking about self-defense, droves and droves of young people wanted to do that.

And I thought that was the best—that’s the best—we followed Robert Williams. And he said, if you are confronted by a racist who believes himself superior, then he has—and you’re armed—he has to consider: Does he want to risk his superior life to take your inferior life? And if you have a gun, you can put him in that position. And nine times out of 10, he doesn’t, and that’s the end of the violence. So we believed self-defense was a way to put a reduction into violence, and I accept that.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Kathleen Cleaver, former communications secretary of the Black Panther Party.

Today, we focus on an overlooked part of the Black Panther Party’s legacy: political prisoners. The Black Panthers were one of the most criminalized movements in U.S. history, with many of its members arrested and sentenced to decades in prison. In some cases, court documents show they were punished essentially for being in the black liberation struggle. In others, it was later revealed that torture was used to extract their confessions.

Over the years, Democracy Now! has interviewed many Black Panthers who eventually won their release from prison, such as a group of men arrested for allegedly killing a San Francisco police officer. Known as the San Francisco 8, their charges were thrown out by a state court because they were based on statements made under torture. This is former Black Panther Harold Taylor describing his arrest in the case on Democracy Now! in 2007.

HAROLD TAYLOR: Well, in 1973 in New Orleans, myself and John Bowman and Ruben Scott was arrested in New Orleans by the police department. We were taken from the place where they are arrested us and took us to the jail. And immediately, when we got in the jail, they started beating us. They never asked us any questions in the beginning. They just started beating us.

They had already had Ruben—they had arrested Ruben earlier that day, before they arrested me and John Bowman. And they put me a room with Ruben Scott when they first got me there, and he had been there a couple hours. Well, he was laying on the floor in a fetus position, where—and he had urine on him, feces, and his face was scratched up, and he was swollen, and he was trembling.

And I asked him, I said, “Ruben, what’s going on?” He says nothing. He doesn’t say anything. He’s just shaking. And then, immediately, the door opens up, and the police pulled me out, and they tell me, said, “If you don’t cooperate, this is what you’re going to get.” They made me take off my clothes, chained me to a chair by my ankles to the bottom of the chair and my wrists to the sides of it, and I just had on my shorts. And at that point, they started beating me.

AMY GOODMAN: That was former Black Panther Harold Taylor speaking about his ’73 arrest and interrogation for a murder charge that was later thrown out.

Now, 50 years after the founding of the Black Panther Party, many former members are still held in prison based on similar tortured confessions. Others were convicted based on questionable evidence or the testimony of government informants. Widely recognized as political prisoners, they account for one of the Black Panther Party’s most enduring legacies.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: This month marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party, and we’re spending the hour focusing on an overlooked part of its legacy: political prisoners in the United States who are former Black Panther members. Perhaps the most famous of them is Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has regularly been interviewed on Democracy Now! as an award-winning journalist. But there are many others. In fact, two former Black Panthers have already died in prison this year: Abdul Majid in New York and Mondo we Langa in Nebraska.

In a web exclusive feature on democracynow.org, we describe other Panthers who remain locked up. They include Romaine “Chip” Fitzgerald, who was convicted in 1969 of attempted murder of a police officer during a traffic stop shootout in which he himself was shot in the head but survived, as well as the murder of a security guard in a separate case based on flimsy evidence. It was the same year the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover declared, quote, “the Black Panther Party … represents the greatest threat to internal security of the country.” Fitzgerald has since suffered a stroke while in prison. Despite his medical condition, he’s been repeatedly denied parole, despite California’s push to release people over age 65 who have served more than 25 years of their sentence.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined now by four former Black Panther Party members who became political prisoners, lived through similar ordeals. All but three of them were released from prison in the last three years.

Here in New York, in his first global broadcast interview, we’re joined by Sekou Odinga, who helped build the Black Panther Party in New York City. He was later involved in the Black Liberation Army. He was convicted in 1984 of charges related to his alleged involvement in the escape of Assata Shakur from prison and a Brink’s armored car robbery. After serving 33 years in state and federal prison, he was released in November of 2014.

In Baltimore, Eddie Conway joins us, former Black Panther leader in Baltimore who was released from prison in March 2014 after serving 44 years for a murder of a police officer. He always maintained his innocence, saying he was set up. We first spoke to Eddie Conway less than 24 hours after his release from prison.

And we are joined from Austin by two former members of the Angola Three who formed one of the first Black Panther chapters in a prison. Robert King spent 32 years in Angola, 29 of them in solitary confinement, released in 2001 after his conviction was overturned. With him is Albert Woodfox. Until February of this year, Woodfox was the longest-standing solitary confinement prisoner in the United States. He was held in isolation in a six-by-nine-foot cell almost continuously for 43 years at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola. He was released on his 69th birthday. We spoke with him two days later, and I asked him at the time how it felt to be free.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Being released into society, I am having to learn different techniques, you know, of how to—I’m just trying to learn how to be free. I’ve been locked up so long in a prison within a prison. So, for me, it’s just about learning how to live as a free person and just take my time. Right now, the world is just speeding so fast for me, and I have to find a way to just slow it down.

AMY GOODMAN: Albert Woodfox, speaking on Democracy Now! last February, just days after his release.

We welcome him and all of you to Democracy Now! I want to begin in Austin with Robert King and Albert Woodfox. You just came from Oakland, California, where you were at the 50th anniversary discussions, celebration of the founding of the Black Panther Party. How did it feel, Robert King?

ROBERT KING: It was—I thank you, Amy. It was great, the commemoration of the 50th anniversary. It marks, I think, a turning point in our approach to, and you stated, dealing with political prisoners, prisoners who have been left behind. We focused on a lot of things, but the main focus was—in my opinion, was focusing on the political prisoners. While everything else was important, and most likely we will get to that, but the political prisoners aspect was the point that caught our attention, that catches our attention at this point in time, because we’re at crunch time with regards to our political prisoners, and I think we need to focus on our political prisoners. I mean, and we have to go across the board. We have to devise the language to validate, you know, our contention and our—the approach that we have in trying to rid these gulags of our political prisoners and political victims, as well, which is another story.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Albert Woodfox, the whole idea of starting chapters of the Panthers in prison, which happened across the country, and many people are not aware of, what initially inspired you to do that? And your sense of comradeship, when you went to this conference, with people who had been on the outside, as well?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, for me, the horrible conditions, the brutality and the constant murdering and raping of young inmates necessitated that something be done. Since I had joined the Black Panther Party while in prison, I felt as though the best way to address these horrible conditions was by forming a chapter, along with Herman Wallace and Robert King, to combat these horrible conditions. You know, newly joining the Panthers while in prison, I knew no other way other than to uphold the principles and the values of the Black Panther Party to do this.

AMY GOODMAN: You know—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what was the—what was the reaction of the prison officials to your attempt to organize inside?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, at the time, I think we were—lasted as long as we did, we were as successful as we were, because they had an internal struggle going on in Angola between what’s called the old families, families that go back generations, and—I think the secretary, Elayn Hunt, DOC Secretary Elayn Hunt, who I think was the first female secretary they had ever had, had brought in personnel from outside—the warden, Murray Henderson—and he, in turn, brought in people from outside. And so, given this internal struggle between the old families and the personnel brought from outside of Louisiana, their concentration was on that rather than on the organizing that myself and Herman Wallace and Robert Wilkerson was participating in, you know, in the prison population.

AMY GOODMAN: Albert Woodfox, we played the clip of you right after you got out of prison, and then we came down to New Orleans and saw you, met you. It’s almost a year since you’ve been out. How are you doing now? This was—I mean, you are the person held in solitary confinement longer than anyone in U.S. history, for over 43 years.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, I’m doing well. You know, I’m constantly adjusting to being a free man after such a lengthy time being in prison. I’m enjoying the comradeship of former Black Panther Party’s members and as well as being embraced by my community, my family. And the one thing I have learned is that living free is a constant adjustment. So I don’t know if I will ever stop adjusting to how society constantly changes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, we’re also joined here in studio by Sekou Odinga. Talk to us about how you originally got involved in the Panther Party, what drew you to it and how it shaped your own life.

SEKOU ODINGA: I got involved in the Black Panther Party early 1968, when the party first come to New York. What kind of motivated me to join the Black Panther Party was that I, along with some of the comrades that I was working with in New York, had heard about the Black Panther Party, and they were doing things that we wanted to do in New York, and we thought that would be a better vehicle than the vehicle that we had going on in New York. They were better organized, and they already had their Ten-Point Platform and Program, and people already heard about them. So we decided that we would join the party, when given a chance. In fact, a few of us had actually went out to California in late ’67 to check it out, to see if was it all we thought it was, and we had found out from them that it was. And so, when we heard they were coming to New York, we got there and joined the party as soon as we could.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But even before that, you were also a member of Malcolm X’s Organization of African-American Unity.

SEKOU ODINGA: Yes, I was, right before he passed. But he passed right—you know, the Organization of Afro-American Unity was only a year old, maybe less. I can’t even remember exactly how long. So, we didn’t really get a chance to do much work in that organization. I had been attracted by Malcolm X when he was still a member of the Nation of Islam. And I was in a—supposed to have been a youth prison, but it was really just a prison that they had turned over and said now it’s for youth. I was 16 years old when I went in there. And when I come out, I was looking for him to see if—you know, to hear him, to see him, to see if I wanted to be a part of what he was dealing with. So, it took me about two years before I actually joined, maybe a little less, but I didn’t spend much time with it. We tried to organize our own organization called the Grassroot Advisory Council. That was the group that I was saying that we were part of, that we were—thought that the Black Panther Party would have been a better vehicle for us to participate in, which is what we dropped and went into.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about how being in the Black Panther Party shaped your case, how you ended up in prison.

SEKOU ODINGA: Well, as one of the leadership of the Black Panther Party in New York, I was the first Bronx section leader when it first come to New York, and I was also a member of the—founding member of the international section of the Black Panther Party in Africa, Algeria. So I was kind of one of those identified by COINTELPRO as someone to maintain, to follow, to listen to, to control any way they could. So—

AMY GOODMAN: That’s J. Edgar Hoover’s Counterintelligence Program.

SEKOU ODINGA: Yes. And so, I think once they realized who I was, after my capture—when they first captured me, they didn’t know who I was. And there had—although there had been what they call a shootout, there was no real shootout. We were running, my comrade and I, Mtayari Shabaka Sundiata. We were running from the police. He had been involved in a action up in Rockland County, and they were looking for him, and I was trying to help him get out of New York. And so, we were running from the police, and we both shot over our shoulders while we were running, hoping to slow them down, so we could try and get away. But so when we was first captured—well, he was murdered on the street. When they caught him, they knew who he was right away, and they murdered him laying on the street.

But they didn’t know who I was. They hadn’t seen me in about 13 years, so they didn’t. When they brought me in, they at first charged me with something like—if I remember right, it was resisting arrest and having an illegal gun, or something to that nature, under Sullivan law. But after my prints come back and they found out who I was, later on that night or the next day they—actually, it was the next week, if I remember correctly. It’s been a while now. This is back—we’re talking about 34, 35 years ago. But later on, they upped those charges—

AMY GOODMAN: You were captured in ’81.

SEKOU ODINGA: Yeah. They upped those charges from the resisting arrest, etc., to attempted murder of police, which upped the time that they could give me from a few years to life, because for attempted murder of police, you can get 25 years to life. And that’s what they gave me, six charges—six counts of 25 years to life, or six sentences of 25 years to life running together. So, that’s how I think it changed. Once they realized who I was and that I was one of the targets of COINTELPRO, the charges went from low charges to extra high charges.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And this whole issue you mention of being part of the international section of the party, most, especially young people, a lot of them watching this show, don’t really understand the—necessarily, the impact that the Panthers had, not only in the United States, but internationally. And for a while after, there was a split in the party between Huey Newton and Eldridge. There was a whole group that was working in Algeria, weren’t they? Could you talk about what happened there and your impact in terms of the movements in Africa that were in existence at the time?

SEKOU ODINGA: Well, let me back up a little bit. I don’t think that it was just a split between Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton. There was a split between two factions.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Right.

SEKOU ODINGA: And people have, for whatever reason, identified it as Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Right.

SEKOU ODINGA: But it was like—from my perspective, it was the left and the right, you know, that some people who were on the right, as we can—called it, were moving to the right and moving into mainstream politics rather than revolutionary politics. And those of us on the left was maintaining that we had to be different from that.

Now, to go to the effect that it was—the party was having a big effect all through the world—through Europe, Latin America, Africa. And in many places, support committees came up, in Europe and in Africa. We were able to work with many of the different liberation movements. We were welcomed by all of them that was in there, and almost everyone was in—excuse me—in Algeria at the time. So, I think we had a profound effect on many of the different movements. You were seeing people emulating our Ten-Point Program and Platform, seeing people start to emulate our dress code, the black tam cut to the side and leather jackets and stuff like that.

AMY GOODMAN: And the Ten-Point Program, what was most important to you there? What was it that attracted you to the Black Panthers?

SEKOU ODINGA: Well, the program—the whole program attracted me. But what attracted me more than anything else was the stand against police brutality, because like all the other ghettos in this country or black areas of this country, police brutality was running rampant. From my first memory of it was—in New York was little Clifford Glover, who was murdered out in my neighborhood in Jamaica, Queens, out over on New York Boulevard—Guy Brewer Boulevard, they call it now. So, I think what we were really concerned about was trying to put some kind of control on the police, or at least be in a position that we could counter some of what they were doing. So, that was the attraction, the big attraction, for me, personally, and many of the comrades that I came in with, because they really—we were not part of the civil rights movement to turn—turn your other cheek. We was mostly followers of the Malcolm X position that if someone smack you, you smack him back; if someone punch you, you punch him back; that your life was the biggest and best thing you had, and you had a right to not only protect it, but to defend it by any means necessary. And so, those were the things that really attracted me to the party.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you get out of jail after 33 years?

SEKOU ODINGA: I think—I know that the biggest thing was that I filed a Article 78, which is a legal position in the courts, claiming that New York state had—did not have the right to hold me any longer. Their law basically says that the jurisdiction—I was under two jurisdictions, the New York state jurisdiction and the federal jurisdiction. And the law basically says that the first jurisdiction, the controlling jurisdiction, has to exhaust their remedies with you before giving you to any—to another jurisdiction. And I maintained that they didn’t do that, that once they gave me up, then they lost control of me, because that’s what their law says. And basically, the judge agreed with me, and he ruled that—only thing he ruled was that they didn’t give me up deliberately, as he put it. He says that “I think they made a mistake,” which the law don’t have no position in there for making a mistake. If you give him up, you lose him. But to save the face for them, he said, “I think that they made a mistake. So, to fix that mistake, what I’m going to do is run the time that you did in the federal system with the time that you were supposed to do in the state system. And I’m going to order them to give you everything that they should have given you if you’d had been in the state,” which he’s basically saying that “You have to give him parole.” So—

AMY GOODMAN: And were you convicted of helping Assata Shakur to escape?

SEKOU ODINGA: That was one of the charges in the federal system.

AMY GOODMAN: And what was your contention?

SEKOU ODINGA: I have no contentions on that at this point. I was found guilty of it. I don’t—if anything, I’m proud to be associated with the liberation of Assata Shakur. So, since they found me—I did plead not guilty to it, if that’s what you’re asking me. I pled not guilty to it in the court case. But at this point that I’ve done the time, I don’t have no contention on it any longer. I’m proud to be associated with the liberation of Assata Shakur. She should have never been locked up for all that time anyhow and treated like she was treated, because it was clear that she didn’t murder any officer, or her comrade, Zayd Shakur. So, I am—that’s my position now.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Sekou Odinga here in New York, Albert Woodfox and Robert King in Austin, Texas. They’re about to go on a European tour talking about their experiences in jail, the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party and more. When we come back, Eddie Conway will join the conversation, served over four decades in prison. He’s joining us from Baltimore. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “The Meeting” by Elaine Brown, here on Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. Elaine Brown, a former leader of the Black Panther Party, as well. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: This month marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party, and we’re spending the hour focusing on an overlooked part of its legacy: political prisoners in the United States who are former Black Panthers. I want to bring into the conversation, from Baltimore, Eddie Conway, former Baltimore Black Panther leader, who was released from prison in 2014 after serving 44 years for a murder he denies committing. He was convicted in the killing of Baltimore police officer Donald Sager, but has maintained his innocence, saying that he was set up. For years, Conway’s supporters campaigned for him to be pardoned.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

MARSHALL ”EDDIE” CONWAY: Thank you.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Talk to us about how you got involved in the Panther Party and what—the incidents that led up to your original arrest.

MARSHALL ”EDDIE” CONWAY: Well, primarily, I got involved in the Panther Party as a result of me deciding not to go to Vietnam and come home from the Army, because there was a tremendous amount of riots taking place in the United States in ’65, ’66, ’67. I wanted to see if I could come and help solve whatever problems it was in terms of the black community rebelling like it was, joined the NAACP, worked with CORE, tried to integrate the workplaces. During the process of that, I found out that there were serious problems in the community. Young children were going to school without food. There was no medical care. There was a number of things. The community was under attack by the police departments, etc. So I looked around and identified what I thought was the best organization to address that. It was the Black Panther Party, so I joined the Black Panther Party. We established a—helped institute a medical clinic, a breakfast program, a educational program, community control the police, etc.

And during that period, the FBI, with its COINTELPRO program, decided to destroy the Black Panther Party. And within a year and a half, it destroyed about 25 of our 37 state chapters, ran the leadership out of the country, the primary leadership, or locked them up or assassinated them, and locked up the secondary leadership or either forced them to leave the country. And I was part of that secondary leadership. I end up getting locked up illegally. As a result of a shooting incident between Panthers and police, a police got killed, one got wounded. The other ones engaged in a shootout. A couple days later, I was put in with two other Panthers that had been locked up in the area, and taken from my job and tried, convicted, found guilty and spent 12 years in prison before they made a determination that we had all been tried illegally in the state of Maryland according to the law, but it took another 32 years to actually win our release, or win my personal release.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Eddie Conway, one of the—you mentioned that wave of repression, first of the top leadership, then of the secondary leadership. One of the things I remember was, years after that repression occurred, The New York Times reported about a secret poll that the federal government had done and where the federal government concluded that at least 25 percent of all African Americans in the country were supporting the Black Panther Party. So they were deeply worried that the black community was being increasingly radicalized as a result of your efforts.

MARSHALL ”EDDIE” CONWAY: Well, not only that, but their problem was that we worked—we formed alliances with groups in other communities, the Native American community, the AIM. We formed alliances with the Latino community, the Brown Berets; with the Puerto Rican community, the Young Lords; the white community, the Patriot Party, White Panther Party, etc. We formed alliances throughout the country, but alliances were also being formed and our programs were being duplicated in India, in Israel, in Africa, in Europe, in the Caribbean and so on. So it was those ideas that were spreading and that unity in terms of creating alliance that scared the government the most. And so, they weren’t just concerned about what was happening in the black community, but they was concerned about the ideas of international socialism spreading throughout the radical communities around the world taking an example from our—the way we were building and organizing.

And they had to disrupt that building and organizing. And the only way they could was they labeled us as black militants with only a self-defense component, and they goaded us into—by killing us, assassinating us, blowing up our building and whatnot, they goaded us into resisting, protecting the stuff that we had built, and it actually led to a split, for the want of a better term, between those of us that thought that building a broader base among the masses was the correct way to go and those of us that was tired of being persecuted and attacked and tired of seeing our members assassinated.

AMY GOODMAN: Sekou Odinga, while you’re out of jail, you’re very much focused on those who are still in prison. Can you talk about some of those cases?

SEKOU ODINGA: Yeah. We have a number of brothers left in the prisons, about 15 of them. And for the most part, they’re in bad condition. Most of us are getting older, you know. I believe all of them is 60 years or older. They’ve been in prison for long periods of time. Many of them should have never been in prison at all. They were framed and illegally convicted. So, I’ve been trying to, as well as many of the other brothers—I know all three of the other brothers that’s on this program with us have been advocating for the release of these other political prisoners, prisoners like Mumia Abu-Jamal, Sundiata Acoli, Mutulu Shakur, Robert Seth Hayes, Kamau Sadiki, Veronza Bowers. It’s another—like I say, it’s 15 from the party itself, and there’s many other political prisoners in this country.

You know, this country maintains that there is no political prisoners, that everybody is criminals, but it’s just not true. You know, the same—the same things that we hurray and support in other places, like people like Nelson Mandela, our prisoners were doing the same thing, and they were captured and convicted of the same things. And we should remember them and treat them like the heroes they are. They earned that respect. Most of them, like I said, are getting older. A lot of them are sick.

You know, a lot of them are being held even after the courts have ordered them released, people like Veronza Bowers, who was—did all of his time and then was—after he was on his way out, they locked him back up, with no charges, and he’s been locked up now for over 11 years, 11 or 12 years now, after he did all of his time. Sundiata Acoli was—won in—won a court case where the judge ordered him released, and they refuse to release him. And they keep going back with appeals so they can keep him in jail. Now he’s almost 80 years old. You know, it’s—

AMY GOODMAN: In Sundiata Acoli’s case, the judge ordered the parole board to “expeditiously set conditions” for his release. He said then of his June 2016 New Jersey Parole Board hearing, they asked me “almost nothing about my positive accomplishments. They … asked: ’Aren’t you angry … they broke Assata out of prison instead of you?’ My response was: 'No, I don't or wouldn’t wish prison on anyone.’”

SEKOU ODINGA: Yeah. So, these brothers need to be released. And we need to—first of all, we need to know who they are. People don’t even know that we have political prisoners. Most of the names that I mentioned, most people wouldn’t even—wouldn’t recognize it, if they’re not already politically involved. We want to raise their names up to a point where people will start knowing who they are and start demanding their release.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Is there any hope that President Obama might do something before he leaves office?

SEKOU ODINGA: Yes, there’s hope. There’s definitely hope. And I’m sure that those—well, I know for a fact that the prisoners, the political prisoners in the federal system, is asking him for clemency or for some kind of release. I don’t know if he’s going to recognize them and help them. But—

AMY GOODMAN: Albert Woodfox, earlier this month you had the opportunity to meet the U.S. District Judge James Brady of the Middle District of Louisiana, who issued the order saying you should be immediately released and barred from being retried for the killing of the Angola prison guard, Brent Miller, whose former wife even said she did not believe that you had done this. Judge Brady later said, quote, “I did what a judge is supposed to do.” We only have a minute, but what was it like to meet him? And the power of judges in some of these cases, as prisoners, Black—former Black Panthers, are still seeking release?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, you know, at the time, I was speaking at Southern University Law School in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. And it was a total surprise to know that Judge Brady was in the audience. And so, after speaking with the law students and attorneys and other people involved in the judicial system, I learned that Judge Brady was there, and I wanted to thank him for having the courage to apply the law and not allow my being a former Black Panther Party or my activism in prison to cloud the issues, and to apply the law. And that’s exactly what he’d done. You know, of course, we know that the state of Louisiana, mostly through the Attorney General Office, continuously appeal his rulings, and in most cases his rulings were reversed or stayed. And this process was drug out over a 44-year period.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there, but it’s been a fascinating discussion. I want to thank Albert Woodfox and Robert King, now in Austin; Sekou Odinga, joining us here in New York; and Eddie Conway in Baltimore. Go to democracynow.org for our special report on the Black Panthers who are still behind bars to find out more about their cases,

Media Options