Topics

Guests

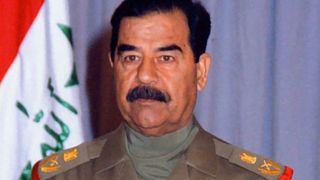

- John Nixonformer CIA analyst and author of the new book, Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein.

Ten years ago this week, on December 30, 2006, former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was executed. Hussein was toppled soon after the U.S. invasion began in 2003. We continue our conversation with former CIA analyst John Nixon, author of the new book, “Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, 10 years ago this week, on December 30th, 2006, former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was executed. Hussein was toppled soon after the U.S. invasion began in 2003. U.S. President George W. Bush launched the invasion on the false premise that Hussein had stockpiled weapons of mass destruction and had ties to al-Qaeda.

AMY GOODMAN: Now we bring you Part 2 of our conversation with CIA senior analyst John Nixon. He was the first person to interrogate Saddam Hussein after Saddam was captured. Nixon is the author of the new book, Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein.

Were you for the invasion of Iraq?

JOHN NIXON: Yes, I was. Back in 2002, 2003, I believed that if we removed him from power and then made Iraq a better place, that the Iraqis would—you know, that would be better for Iraq and that we could help turn the country into a functioning, hopefully democratic, country that, you know, would be as good as what the Iraqi people deserved.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you change your view?

JOHN NIXON: A hundred percent. When people ask me, you know, “Was it worth taking him out of power?” I say, “You know, look around you. Show me something that is positive that happened.” Iraq, right now, is a country that has 2 million displaced people. Parts of its territory are held by ISIS. You have a dysfunctional government that is probably more corrupt than Saddam’s government was. And if ask the average Iraqi—Sunni, Shia or Kurd—you know, “Were things better back then? Were services better? Did the government do more for you?” I think they would say yes. I can’t find one thing. And if you said, “Well, maybe, what about the Kurds? They’re almost independent now,” that was happening already. I can’t find one thing positive that came out of his removal from power.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I want to turn to President George W. Bush giving the State of the Union in 2003.

PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH: Year after year, Saddam Hussein has gone to elaborate lengths, spent enormous sums, taken great risks to build and keep weapons of mass destruction. But why? The only possible explanation, the only possible use he could have for those weapons, is to dominate, intimidate or attack. With nuclear arms or a full arsenal of chemical and biological weapons, Saddam Hussein could resume his ambitions of conquest in the Middle East and create deadly havoc in that region.

And this Congress and the American people must recognize another threat. Evidence from intelligence sources, secret communications and statements by people now in custody reveal that Saddam Hussein aids and protects terrorists, including members of al-Qaeda.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That was President George W. Bush—

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —in 2003, two months before the U.S. invasion, attempting to justify the events that were coming. You eventually got to brief President Bush directly. But by then, a lot had changed in terms of what the United States understood had actually happened before the invasion.

JOHN NIXON: Sure. We finally were asked to brief the president in 2008, which was five years after Saddam’s removal from power.

AMY GOODMAN: And four years after you debriefed President Saddam Hussein.

JOHN NIXON: Yes, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s shocking that the president didn’t want to meet you immediately afterwards, President Bush, to find out exactly what you learned.

JOHN NIXON: Well, you know, the FBI came out and said in early 2008 that Saddam said he was going to reconstitute his weapons program, which was not true. And then, all of a sudden, the White House came to the CIA and said, “You never told us this. What else did he say?” And we had to kind of walk this all back and say, “Listen, he never said that.” The FBI’s assertion was based on a statement that Saddam said—he was asked by the special agent about weapons of mass destruction: “Were you going to reconstitute your program?” And Saddam gave the answer, “I will do what I have to do to protect my country.” And that was the basis upon which the FBI established that he was going to reconstitute the weapons program. The problem is, Saddam gave that answer to just about everything. And, you know, something—Saddam was deliberately ambiguous in his statements. And it’s one thing to say that, but we found no evidence whatsoever of any plans on the part of Saddam or his government to reconstitute his weapons program.

AMY GOODMAN: So—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, you’re critical of what the—the enormous gap between what the intelligence community understood Saddam was doing and intended to do and what you later confirmed to be true. How difficult was it to put this into print? Because you had to obviously go through the CIA to get approval for this book to be—to be approved.

JOHN NIXON: Yeah, it was a—it was a chore. And it was—it took far too long. I originally submitted the manuscript in 2011. And—

AMY GOODMAN: Five years ago.

JOHN NIXON: Yes. And to be honest, you know, some of that was—you know, I got it back from them, and then I took a year or two, because I was working abroad, and I didn’t necessarily want to identify myself as a former CIA person. But when I came back in 2014, I immediately gave it back to them, and I didn’t receive it back until October of this year. And it was—and the things they took out were kind of ridiculous. And it was—

AMY GOODMAN: Can you share with us some of the things that have been omitted?

JOHN NIXON: Well, there were some really great anecdotes. And, you know—but, for example, they took out—we had a certain phrase that we used to describe the building that we worked in. I can’t say that, you know, because they say it’s classified.

AMY GOODMAN: In Iraq?

JOHN NIXON: Yeah, in Iraq, where the CIA station was, the kind of vehicles we drove around, which, you know, I can tell you right now they weren’t Toyotas, you know, Camrys. And they took that out. Then there were some—there were a few—as I said, some anecdotes that I thought really gave color to the story. And for reasons that are beyond my understanding, they took them out.

AMY GOODMAN: But Juan asked you about that meeting in 2008, when—

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —after years after debriefing Saddam Hussein, which you described in Part 1 of this conversation, you meet with President Bush in the Oval Office.

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Describe that meeting.

JOHN NIXON: OK. Well, that was in January of—or, sorry, February of 2008. And I had actually gone there to brief about something else, about Muqtada al-Sadr. And then, the DNI had said, “Mr. President, this is also the man who was the first to debrief Saddam Hussein.” And he just kind of looked at me, and he said, “How many of you fellas debriefed him? Huh, I mean, there’s been a whole lot.” And I said, “Well, I don’t know who you’ve spoken to, Mr. President, but I was the first one, first one from the CIA.” And then he said, “Well, what kind of man was he?” And then I explained it to him. And then I—

AMY GOODMAN: What did you say?

JOHN NIXON: Oh, I said, you know, he was—he could be very charming. He could be very nice. But he could also be very mean-spirited and vicious and a little scary at times. There were kind of—he was sort of a jumble of contradictions, in that sense. And then I said—he said to me, he said, “Did he know he was going to be executed?” I said, “Yes, Saddam—Saddam knew that somehow this whole process was going to end in his death.” And he said—and I said that he was—he was at ease with that. He was—he felt that, you know, he was at peace with himself and God. And so, that’s when President Bush went—he sort of smirked and went, “Huh! He’s going to have a lot to answer for in the next life.” I said, “Well, OK. I’m sure he’s not the only one.” And then he said—oh, when we were leaving—and this really kind of set me back. And I had heard that President Bush sometimes liked to use humor at inappropriate moments. But we were done, and we were walking out of the Oval Office, and then he turned back to me. He said, “Hey, he didn’t tell you any—where any of those vials of anthrax were, did he?” And, of course, everybody broke up. And I said, “No, sir. You’d be the first to know if that was the case,” and left.

AMY GOODMAN: But he wasn’t the first to know a lot of things, or he was, and we didn’t know this. For example, you talked about Saddam Hussein saying there was a letter that he sent to President Bush—

JOHN NIXON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —that he was surprised after September 11th the U.S. didn’t reach out to Iraq to fight extremism and al-Qaeda.

JOHN NIXON: Yes, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: What was in that letter?

JOHN NIXON: He basically expressed sorrow over 9/11. And largely, it was a letter that just said, you know, “I grieve with you, and I grieve for the American people, and that terrorism is a bad thing. Iraq has also been the victim of terrorism”—words along those lines. But it was not the first time that Saddam had reached out to the U.S. government. Even during the Clinton years, Saddam had made entreaties to the U.S. government and said, “Listen, we can help in this battle against Sunni extremism.” He had offered to help—help with our finding the people who were responsible for the first World Trade Center attack in 1993. However, you know, I think our government interpreted this as a sort of a ploy for a quid pro quo, that somehow if we got this, then we would give—we’d let him out from underneath sanctions. And largely, his pleas were ignored, I mean, not even answered. And I think that, in hindsight, you know, these were missed opportunities. And it speaks to this issue about sometimes—sometimes countries have got to—we all do terrible things, but sometimes countries have got to let bygones be bygones and work constructively, because we can achieve things through dialogue rather than just by—through enmity and trying to destroy one another.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And when you look back at all of the hundreds of thousands of people who have been killed and the economies destroyed, not just in—not just in Iraq, but in Syria—

JOHN NIXON: Certainly.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —and in Libya, by the determination of the United States government to remove what are essentially secular authoritarian leaders—

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —and then not being able to deal with the consequences—

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The quote that you have in your book about Saddam Hussein saying, “You’re going to fail, because you don’t understand the language, you don’t understand the history of this area, and you don’t understand the Arab mind.”

JOHN NIXON: It sent chills down my spine. Yeah, I have to be honest with you. When I was talking to him, there were times when he would say things, and I would—I would just be—you know, this is terrible, because he’s making so much sense. And even 10 years later, when I was going through my notes, I was really struck by some of the things he said. And you know it’s a bad day when Saddam Hussein is making more sense than your own president of the United States. And, you know, he—I believe that when it came to understanding Iraq and Iraqis, he knew his country like the back of his hand, and he knew it far better than we.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to Saddam Hussein in his own words. In February 2003, he told CBS’s 60 Minutes Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction.

PRESIDENT SADDAM HUSSEIN: [translated] I think America and the world also knows that Iraq no longer has the weapons. And I believe the mobilization that’s been done was in fact done partly to cover the huge lie that was being waged against Iraq about chemical, biological and nuclear weapons. That is why, when you talk about such missiles, these missiles have been destroyed. There are no missiles that are contrary to the prescription of the United Nations in Iraq. They are no longer there.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Saddam Hussein being interviewed by Dan Rather on 60 Minutes. This is, what, a week or so after we saw the—President Bush making his push for war.

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And it was a month before the U.S. invaded Iraq.

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: When you spoke to him afterwards—first, I just find it astounding that you weren’t brought right to the president to describe what you learned, except, as you say, they actually covered that up at the time, on the issue of weapons of mass destruction, what he’s telling 60 Minutes in February.

JOHN NIXON: They just didn’t really want to know anything but, basically, where it was. And to be honest with you, when we came back, to be fair—I have to be fair. When we came back to the United States in 2004, all hell was breaking loose in Iraq. And I think that they just decided that, OK, we didn’t find the WMD. It’s—nobody wanted to revisit this. You know, when you say something about President Bush, one of the things that really struck me—there was another session I had with Bush, where, you know, he made this statement that I thought was just unbelievable, especially in light of what’s happening. And this was at a 2008 meeting in May. And I told him that maybe we should—you know, he said, “Well, what do we do about Muqtada al-Sadr?” And I said, “Well, maybe we should let Sadr be Sadr, and he’ll do things against himself. He’ll make mistakes.” And then, Bush said—he cut in, and he just said, “Well, you know something? They said I should let Saddam be Saddam, and I proved them wrong.” And so, even by 2008, he still thought that this was a success, that this—

AMY GOODMAN: Did you torture Saddam Hussein to get information?

JOHN NIXON: Absolutely not. You know, if talking to me is torture, that’s one thing. But, you know—but, no. And to be honest, a member of—the head of my team originally wanted to use enhanced interrogation techniques on him, and that was quickly shut down. And thank God. It would have served no purpose. There was no immediate threat information that we were looking for from him. And, you know, so we didn’t use that.

AMY GOODMAN: A message—

JOHN NIXON: He did claim later, though, that we did.

AMY GOODMAN: A message you have for Donald Trump, who says that he would engage in more torture, authorize it?

JOHN NIXON: President-elect Trump, I would just say, I believe, having worked on debriefing prisoners, that it simply doesn’t work. There are better methods to use to get information. And if Donald Trump really is hell-bent on torturing people, he might have to do it himself, because I don’t—after what has happened over the last 10 years and what people went through at the CIA, how are you going to actually find somebody who’s going to be wanting to like cut their own throat by torturing for you and then find themselves the subject of some investigation and legal action?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: One of the things you raise in your book is that you believe that the CIA, over the past couple of decades, has been increasingly corrupted into an agency that provides the intelligence that the current president wants, rather than what they need to hear. Could you talk about that?

JOHN NIXON: Well, sure. It’s what I call the cult of current intelligence. And current intelligence are these sort of short, pithy memos that get produced every day and tell a story about a certain important topic. And it becomes like—the policymakers become very addicted to this, because they want to know the latest and the greatest as they go into every meeting. But the thing is, in the analytic cadre at CIA, it creates a mentality of being so focused on the here and now that you can’t see the larger picture. And you don’t have time to study the larger picture, because you’re constantly churning out these sort of—and over time, you go back and you look at these current intelligence pieces, and, A, they’re overtaken by events, so they’re not really useful; B, some areas, they’re just wrong; and, C, it’s sort of like having—being thirsty and—being thirsty for a Coke, and then, all of a sudden, three months later, you go back for the Coke, and you drink it, and it’s flat, and you don’t want it.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But I’m curious how you can get, especially in terms of Iraq, something so completely wrong, as we saw some of the statements that President Bush made to Congress. To what degree did the United States have extensive human assets on the ground in Iraq before the invasion? Or was it basic—in other words, what was the source of the intelligence? I know you can’t—you can’t reveal your—

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: There are certain conditions. But, in other words, the quality of the information you were getting, how was it developed?

JOHN NIXON: One of the other great lessons that we should have learned from Iraq is that it is very important for us to have a presence in the country, and a presence through an embassy. And you know something? Our sources of information came from émigrés and all sorts of people outside the country. And it was—you know, some of it was good, and some of it was terrible. And the thing is, nothing can replace your ability to be—have your feet on the ground there and see what’s going on for yourself.

AMY GOODMAN: Did Saddam Hussein predict the rise of ISIS?

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: How?

JOHN NIXON: Yes. He had—there’s a passage in my book where he talks about, you know, saying that Sunni jihadism is going to—Iraq is a playing field for this, and it’s—now that he’s out of power, it’s going to be made worse, and that we’re going to have to deal with this issue. He was very concerned. Saddam was not afraid of almost anything, but he was very concerned about the threat that Sunni jihadists had for his regime, largely because they came from within his own community, and it was harder to sort of get—through tribal networks, it was harder to kind of root them out than it would be if they were from the Shia or the Kurds. And also, he understood that this current of Wahhabism that emanated from Saudi Arabia had been infiltrating Iraq for some time, and he was less and less powerful to do something about it. And he also knew that—Saddam was not a jihadist himself, and he didn’t have any alliances with al-Qaeda or—you know, or Sunni fundamentalists. But—

AMY GOODMAN: What did you feel when you continually heard the U.S. media repeat this, making no distinctions and saying he was a haven for terrorists?

JOHN NIXON: It’s ridiculous. You know, it is—and I even asked him about this, and he just—he just kind of laughed. And he said, “You know, these people are my enemies. And, you know, why would you think that I’m allied with”—and then he would use this counterfactual. He’d say, “Well, who was on the plane that flew into the World Trade Center? How many Iraqis were on that plane? But who were they? There were Saudis. There were Egyptians. There was an Emirati. Those are all your friends. Why do you think that they’re doing that?” And then he would also say—one of the things that was most compelling was he would say, “You know something? When I was a young man, everybody admired America. Everybody wanted to go to America.” You know, he used to say he would see at the American Embassy in Baghdad people lining up to get visas. And he said, “And now, look at you. Look at—you know, no one likes you. No one trusts you.” And that was based on the policies of our government.

AMY GOODMAN: What did you think about the execution of Saddam Hussein?

JOHN NIXON: It was chilling. It was—and it was—I knew that it was going—that he was going to be executed. And I thought that this would at least give—he would be tried, he would be—the verdict would be rendered, and then he would be executed, and that maybe this would give the Iraqi people closure, and they could move on, and they would know that the rule of law had been established. But instead what we had was a mob lynching in the middle of the night, where he was taken into the basement of a ministry building and taunted by his executioners. And Saddam looked like the most dignified person in the room.

AMY GOODMAN: And then you see, from a cellphone video—

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —his throat slit and a gaping wound, head twisting sharply to one side.

JOHN NIXON: Yeah, yeah. It was—it was really awful. And I remember thinking it’s like—”Is this what we fought this war for?” You know? And then, subsequently, every time I went back to Iraq, it just kept getting worse and worse. And I remember thinking, “This is—this is ridiculous. This is not what we—this is not what we expended 4,000 lives for.” Not to mention the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who died.

AMY GOODMAN: Mike Pompeo, Donald Trump’s pick—

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —to be head of the CIA, objected to the 2014 Senate torture report, saying, “These men and women are not torturers, they are patriots. The programs being used were within the law, within the constitution.” John Nixon, you are the former senior CIA analyst who first interrogated Saddam Hussein. Do you believe that?

JOHN NIXON: You know, again, I—I don’t believe that these methods work, and I think they’re barbaric, and I would not want to—and I would not participate in anything like that. If Mike Pompeo wants to say that for political reasons, fine. I hope that he—when he’s confirmed as—if he’s confirmed as CIA director, that he does not try to institute anything like that, because, again, he’s not going to find any takers, because I don’t think anybody wants to do this.

AMY GOODMAN: Were you involved in interrogations of any members of ISIS later on?

JOHN NIXON: Well, no. I was involved in interrogations of al-Qaeda in Iraq people, who are the precursor of ISIS. I worked on the Zarqawi hunt in 2006.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you talk about that and what happened to him?

JOHN NIXON: Certainly, certainly. I worked on the—actually, on the portion of the hunt that led to his eventual finding and death by bombing. And it was—I remember thinking to myself, after having interviewed a lot of Baathists, the al-Qaeda in Iraq people made me think like the Baathists were like the royal family in Great Britain, you know, because these people were absolute killers and thugs. And it was something that I said to myself, I remember, “This is what happens when we remove Saddam from power. It’s like ripping the manhole cover off the sewer and seeing what crawls out.” And that was what al-Qaeda in Iraq was like.

AMY GOODMAN: John Nixon, you wrote Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein. Why? What made you decide to do this?

JOHN NIXON: From the very moment I saw him, I knew I was going to write something someday. But having said that, I would say that I—two things. I began to see the memoirs coming out and the sort of gibberish that were in the memoirs of the principals that were—

AMY GOODMAN: When you say “the principals,” you mean?

JOHN NIXON: President Bush, Prime Minister Tony Blair, Donald Rumsfeld, George Tenet—and talking about Saddam—

AMY GOODMAN: George Tenet was your boss.

JOHN NIXON: Yes, exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: Head of the CIA.

JOHN NIXON: And talking about Saddam and also talking about the debriefings and then some of the things that happened in Iraq. And I remember thinking, you know, this—there has to be sort of a more accurate record. And I’m a trained—

AMY GOODMAN: Did they lie about what you found?

JOHN NIXON: They—yeah, absolutely. For example, one of the first things I worked on was the—this reporting that said that Saddam was going to send—was sending hit squads to the United States to kill George W. Bush’s daughters, Barbara and Jenna—I think that’s their names. Now, we now know Saddam couldn’t even get good reception on his radio, let alone be sending hit squads from his intelligence service to America to kill anyone. And yet, in the memoirs of Bush and Tenet and Rumsfeld, they all talk about this as if it was real, as though this is a justification that they’re holding onto. And you know something? It’s not real, and it’s not truthful.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you see is the future of Iraq?

JOHN NIXON: Oh—

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think it will remain a country?

JOHN NIXON: I see—I see, for the foreseeable future, it being kind of similar to what it is now: a dysfunctional mess, in which you have—it does not achieve its potential, it is dominated by Iran, and it is just sort of a failed state.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think it can recover from the U.S. invasion?

JOHN NIXON: I think—I think that it would take a great deal to sort of put the genie of sectarianism and sectarian feelings that have been loosed by Saddam’s removal back in the bottle. And I’m not sure if it can.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think the U.S. invasion of Iraq was a catastrophe for Iraq?

JOHN NIXON: Yes, absolutely. There is not—there is not a shred of doubt in my mind about that.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think it was a catastrophe for the United States?

JOHN NIXON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And for the Middle East?

JOHN NIXON: Yes. We should—we should never have gone in there. And you know something? If the Iraqi people wanted to remove Saddam, that was for the Iraqi people to do, or for God to do. You know? And there should have been an Iraqi solution to what came next, not an American solution.

AMY GOODMAN: What is your biggest regret?

JOHN NIXON: My biggest regret, in terms of Iraq, was the damage that was done to that country by my country and my own participation in this. And I wish there was some way we could—we could help the Iraqi people and help them rebuild what they—what they may have had. And, you know, it’s a great country with great people, and they have a lot going for them, and there is no reason why it should be failing like it is.

AMY GOODMAN: John Nixon, former senior CIA analyst, the first person to interrogate Saddam Hussein. He’s the author of the new book, Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein. That’s Part 2 of the conversation. To go to Part 1, go to democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options