Topics

Guests

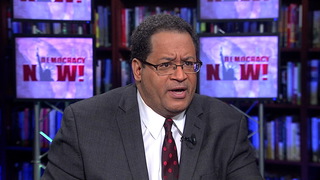

- Michael Eric DysonGeorgetown University professor, political analyst and author of 17 books. His most recent is The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America.

Web-only extended interview with Michael Eric Dyson about his new book, “The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue with Michael Eric Dyson. The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America is his latest book. In Part 1 of our conversation, we talked about some of the defining issues of his presidency. Michael Eric Dyson, talk about the interview itself with President Obama, when you conducted it, in the midst of the book. Where did you do it, by the way?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: It was in the Oval Office of the White House. And—

AMY GOODMAN: Had you ever been there before?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: I had never been to the Oval Office before. I’d been to the White House, but not to the Oval Office. That was quite a treat. And when Obama, after our interview—I’ll talk about what he said later—but, you know, he took me to the—that powerful bust of Martin Luther King Jr. And he was quite proud of that, that he had installed that in the White House, in the Oval Office. I think Winston Churchill left, and Dr. King came in. And that was quite a transition of powerful symbols in that space. And, of course, he was—

AMY GOODMAN: When did he put it in?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: He put it in right when he went into the Oval Office in 2009. So it was extraordinary for him to do so. And look, he’s a genial, affable, charismatic man. There’s no question about that. Even when you disagree with his policies and engage him, as a human being, I think he’s a very decent and honorable man. And then, when you contrast that to some of the righteous criticisms that have been made of him and the duties that he’s had to undertake as a result of being in that office—when you played earlier his comments in 2009, it was kind of shocking to see all that shock of black hair on his head, and how he has grown gracefully—and, of course, some would say, witheringly—into older age only seven years later, but his hair is full of grey, and I think that’s from struggling with the issues that he’s confronted in that office.

But the interview was during the earlier part of his presidency. He was optimistic about things. I was trying to push back on him. I have gone to the White House several times after that. And in one notable meeting, that Jonathan Alter catches in his book, you know, I confronted him about his beliefs on targeted versus universal policies for African-American people. He believed that a rising tide lifts all boats. He would disagree with that characterization, but that’s the idea. And I said, “Well, I think it has to be targeted.” William Julius Wilson, the great sociologist, at first was the resource for Obama’s belief that you have to be nonspecific strategic deflection of race, but now, Wilson has said, you’ve got to be specific and directed. And I’ve tried to push Obama on that issue, saying that when you go to the emergency ward, you don’t get medicine. If you’ve got cancer, you get chemotherapy. If you’ve got diabetes, you get insulin. If you’ve got a hangnail, you get an aspirin. So I said, “Medicine works best, like public policies, when they’re targeted.” So we had a back-and-forth on that issue, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go back to last year, March, the 50th anniversary of the marches in Selma to demand equal voting rights, President Obama speaking right next to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the event taking place just after the Justice Department issued its scathing Ferguson report, which found African Americans were adversely impacted by Ferguson’s policing and court practices.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: You know, just this week, I was asked whether I thought the Department of Justice’s Ferguson report shows that, with respect to race, little has changed in this country. And I understood the question. The report’s narrative was sadly familiar. It evoked the kind of abuse and disregard for citizens that spawned the civil rights movement. But I rejected the notion that nothing’s changed. What happened in Ferguson may not be unique, but it’s no longer endemic, it’s no longer sanctioned by law or by custom. And before the civil rights movement, it most surely was. […]

Of course, a more common mistake is to suggest that Ferguson is an isolated incident, that racism is banished, that the work that drew men and women to Selma is now complete, and that whatever racial tensions remain are a consequence of those seeking to play the race card for their own purposes. We don’t need a Ferguson report to know that’s not true. We just need to open our eyes and our ears and our hearts to know that this nation’s racial history still casts its long shadow upon us. We know the march is not yet over. We know the race is not yet won. We know that reaching that blessed destination, where we are judged, all of us, by the content of our character, requires admitting as much, facing up to the truth. “We are capable of bearing a great burden,” James Baldwin once wrote, “once we discover that the burden is reality and arrive where reality is.”

AMY GOODMAN: That was President Obama on the 50th anniversary of the Selma—first Selma to Montgomery March, where John Lewis, who was certainly there that day as President Obama delivered his address, got his head smashed in by the state troopers in Alabama, leading 600 people for voting rights.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Mm-hmm, it was extraordinary. I was there that day. A remarkable speech, and heartening to hear the president speak about those issues, and not simply in the past, because he has tended in the past to relegate black anger in a legitimate form to the ’60s, and the manifestation of black anger at injustice now has been, you know, really dismissed. And he has rather underscored the legitimacy of white anger at having to conform, through affirmative action and other policies, to the demands of racial justice. But to see him that day speak eloquently and powerfully about these issues was quite heartening.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it was an incredible moment—Democracy Now!, we were there, as well—100,000 people, far exceeding anyone’s expectations. But then just go three months later to June 26, President Obama delivering the eulogy for Reverend Clementa Pinckney, South Carolina state senator and pastor of the historic Mother Emanuel, the Emanuel AME Church, in Charleston, South Carolina. Reverend Pinckney, along with eight other African-American parishioners, was killed when white supremacist Dylann Roof opened fire during Bible study at the church.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: An act that he imagined would incite fear and recrimination, violence and suspicion. An act that he presumed would deepen divisions that trace back to our nation’s original sin.

Oh, but God works in mysterious ways. God has different ideas. He didn’t know he was being used by God. Blinded by hatred, the alleged killer could not see the grace surrounding Reverend Pinckney and that Bible study group, the light of love that shone as they opened the church doors and invited a stranger to join in their prayer circle. The alleged killer could have never anticipated the way the families of the fallen would respond when they saw him in court, in the midst of unspeakable grief, with words of forgiveness. He couldn’t imagine that. […] Blinded by hatred, he failed to comprehend what Reverend Pinckney so well understood—the power of God’s grace.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, President Obama electrified the thousands who packed in at the College of Charleston. We were there. And, I mean, I don’t know about Dylann Roof, but he clearly, Dylann, began to blow the roof off the Confederacy, right? I mean, the South Carolina flag came home, and then President Obama, delivering this eulogy, broke into song.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound,

That saved a wretch like me,

I once was lost but now am found,

Was blind, but now, I see.

Clementa Pinckney found that grace. Cynthia Hurd found that grace. Susie Jackson found that grace. Ethel Lance found that grace. DePayne Middleton-Doctor found that grace. Tywanza Sanders found that grace. Daniel L. Simmons Sr. found that grace. Sharonda Coleman-Singleton found that grace. Myra Thompson found that grace.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama giving the eulogy in Charleston after the mass killing at the Mother Emanuel Church. The significance of this moment, Michael Eric Dyson?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: It was an epic moment in American political history, where the president literally becomes the preacher to the nation, speaks to them out of the depth of his faith—the faith that 54 percent of the Republicans don’t believe he possesses. But it’s beyond a Christian understanding of the world. It’s for anybody who understands spirit, beyond religious bigotry and tribalism, to understand our connection to each other. And he evoked the best of American ideals. He spoke about black people with empathy and pride and love. He was at his best when he was at his blackest, which has often not been the case. And ultimately, he offered the nation the majestic beauty of grace that black people have evoked in their lives from the beginning of our sojourn here. It was—it was a remarkable moment.

AMY GOODMAN: So you have President Obama taking on police violence, police brutality, addressing the whole issue raised by the Black Lives Matter movement. And then you have his government seemingly undercutting him.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Just a few months ago, right, he holds this big session with police chiefs.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: And you have the head of the FBI, Comey, saying that these police officers have their hands tied because everyone is watching.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Actually, the figures don’t bear that out.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Of course not, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: What’s going on?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, this is—this is the rebellion, within the state, of the figures who are appointed to represent the interests of the people. But this is their rebellion against having to be sensitive to and aware of the rights of black citizens. This is a resentment, you know? “Our hands are being tied, and we are being handcuffed ourselves from doing it. And police people are not doing their jobs, because they fear”—what? That they might be called to attention? That they might be called to accountability for what they’re doing?

AMY GOODMAN: That their actions might be videoed.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: They may be videoed, and as a result of being videoed, that they might be held—found culpable for some heinous acts. So I think that Obama certainly was—Comey certainly did a disservice to Obama’s interests in defending black people. But it was good that he made them clear, so we don’t have to guess. There’s no guesswork involved in that. Comey was pretty clear about what he believed. And, of course, before that, at Georgetown University, he had made an interesting speech about how we have to confront these issues. So even the, quote, “good guys,” the people who are relatively sensitive to the calls and claims of people of color that the police forces are not acting and behaving correctly, ultimately have that snatched back from the very same voice that had expressed that empathy.

AMY GOODMAN: Michael Eric Dyson, let’s go back in time to the beginning of the presidency—

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —to President Obama running for president, to Reverend Jeremiah Wright.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Right, right.

AMY GOODMAN: You devote a good amount of time in the book to Reverend Wright. What happened to him?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Yeah, you know, Jeremiah Wright had been the spiritual linchpin for Obama’s conversion to Christianity. And—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean by conversion to Christianity?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, I mean that he found in Reverend Wright the ideal expression of what it meant to be a Christian. And when he went to join Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, where I was a member along with Obama, under the tutelage of Reverend Wright—little revelation on the Democracy Now! that I’ve never said anywhere else—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean? When was this?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, this was in the—in the '80s. Well, in the late ’80s and early ’90s. And when I met Obama, my wife had arranged a panel discussion on black history in like ’91, ’92, at McDonough University. And it was me; Obama, a guy who had just graduated from Harvard Law School; and Sheryl Lee Ralph, the actress. And Obama and I later had joked; I said, “Yeah, we weren't paying attention to much of each other. We were looking at Ms. Ralph.” Senator Vincent Hughes, that’s all love. I know that’s your wife. She’s a great woman. And you are, too. So, the reality is, I met him then, knew him. We were members of the same church. I’d see him in church. So for those who claim he didn’t go to church, that’s not true. I saw him there.

He heard those fiery sermons, those powerful, eloquent exclamations. And black people don’t take criticism from the pulpit as being un-American. You know, people who listen and “Oh, my god! How could Jeremiah Wright say that?” Well, because prophets are blues artists, singing their dirges and their ditties, as Margaret Walker would say, giving us a sense of what is possible, complaining about what exists, hoping that the transformation prophetically of our existence will occur as we tell the truth in church. Obama heard that. Black people heard that. They never thought that Jeremiah Wright was against the American state. He was trying to make it conform to the ideals it claimed to be moved by.

So, they were tremendously close. And then, when Jeremiah Wright was counseling President Obama, then-Senator Obama, then-state Senator Obama before then, along the path, it was mostly his spiritual insight. He wasn’t getting political, you know, strategy from Jeremiah Wright. But when it came to announce his run for the presidency, that’s when the hell began to break loose a little bit, because of the articles in Rolling Stone and other places about Jeremiah Wright being a bit radioactive. And so they told him downstairs that he would not be able to publicly pray with the president, he would pray privately. That began the rift that eventually was exacerbated with the discovery of the sermon of “God Damn America” and then, subsequently, with Jeremiah Wright’s eloquent defense of himself and then that, you know, tremendously fateful appearance at the National Press Club where, during the questions-and-answer period, you know, he said, “Politicians do what politicians do. And preachers do and prophets do what they do.” And that, you know, Barack Obama took that as an assault upon him. And then it got worse when Father Michael Pfleger, a well-known white priest in the South Side of Chicago at St. Sabina Church, made fun of Hillary Clinton in the pulpit of Trinity United Church of Christ. And after that, Obama cut ties with the church. And Jeremiah Wright, by that time, had been—had resigned—had retired, I’m sorry, from the church, and the Reverend Otis Moss III was there. So that’s the kind of brief thumbnail sketch of the history.

But the deep passion that these two men had for each other and the respect mutually that they had was always clear, even as they understood they had different roles. Jeremiah Wright knew he was a prophet. And he said, “The moment my member, Obama, is elected, I’m going to be critical of him, because I’m critical of the American empire, and I’m critical of those who represent it.” He was quite clear about that. And Barack Obama had no problem with that. At the same time, Barack Obama understood he had to translate the power and efficacy of the prophecy into political actions that might actually work. And so, they knew they had opposed viewpoints about how that would proceed, but no one expected initially that it would land in that kind of a detrimental and controversial departure from each other.

AMY GOODMAN: And how did the fallout affect Reverend Wright? And how did it affect President Obama?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, obviously, it reduced the complexity of his rhetorical genius for 35, 40 years into a sound bite that truncated this man’s reputation and—distorted his reputation, truncated his prophetic pedigree and suggested that he was merely important because—you know, insofar as his relationship to Obama was made public. Well, the man was important way before then. Ebony magazine named him one of the 15 greatest black preachers, which I take to be one of the greatest American preachers, in the country long before Obama came on the scene. And Obama heard some of the greatest preachers in his church. So, after that conflagration, it certainly had an impact emotionally on Reverend Wright and hampered him in the broader American public, but not among the black churches that loved and supported him.

Obama, of course, was seen as a heroic figure, especially by white Americans, because he had a tremendously difficult balancing act. He had to distance himself from what he felt were the inflammatory comments of his pastor, while not dissing his pastor or dissing black religion. It wasn’t perfect, what he did, but it was an amazing balancing act in that speech, the famous race speech that he gave to not only illuminate and enlighten the American society about race, but to save his campaign. It ha a utilitarian bent there. It was like saving—

AMY GOODMAN: And what about—what about that speech that he gave in 2008?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, until the speech at Selma, and then, of course, his eulogy for Reverend Pinckney, it was probably—and it may still remain—his most famous and enduring race speech. It will be to him what “I Have a Dream” was to Martin Luther King Jr., perhaps. It was an incredible speech, a powerful speech, a speech that tried to balance the need of white Americans to feel that he was not a raging racial lunatic, on the one hand, as they mischaracterized his pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Wright, and, on the other hand, he had to let black people know: “I respect the integrity of our prophets and our preachers.” And so, what he did ingeniously was he split the difference between Jeremiah Wright’s prophetic vocation, which made political statements, with which he could disagree, but preserve the integrity of his spiritual affiliation with Obama, and Obama with Jeremiah Wright. And that was tremendously complicated and risky, but I think he pulled that part off.

The part he didn’t pull off well, I think, in that speech was drawing false equivalencies between black anger of the ’60s and white anger now at what must be done to resolve the remaining racial dilemmas in this country, and distancing himself from some of the contemporary expressions of resistance to racial animus, and then, as he has been wont to do, finding fault in black communities in ways that he would never do in white communities. So, in that sense, the speech was more complicated and set the pattern and the template for what he would do later on in much more explicit fashion.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to jump forward to August 2013, President Obama giving a speech marking the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. After laying out a history of challenges and successes in the fight for civil rights, you say in the book that Obama, quote, “gave in to the lust for black reproof.”

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: If we’re honest with ourselves, we’ll admit that during the course of 50 years there were times when some of us claiming to push for change lost our way. The anguish of assassinations set off self-defeating riots. Legitimate grievances against police brutality tipped into excuse making for criminal behavior. Racial politics could cut both ways, as the transformative message of unity and brotherhood was drowned out by the language of recrimination. And what had once been a call for equality of opportunity, the chance for all Americans to work hard and get ahead, was too often framed as a mere desire for government support—as if we had no agency in our own liberation, as if poverty was an excuse for not raising your child, and the bigotry of others was reason to give up on yourself. All of that history is how progress stalled. That’s how hope was diverted. It’s how our country remained divided.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama in 2013. You were there at that speech.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: I was there.

AMY GOODMAN: Fiftieth anniversary of March on Washington.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: I was right there, right behind the Reverend Al Sharpton in the VIP section there. And I was stunned by that passage and, quite frankly, appalled, because the president was essentially blaming stalled progress on racial relations in America on the very victims of white supremacy and bigotry and racism and bias. It was remarkable. And then saying, as if, you know, racism and bigotry were reason to give up on yourself. Yeah, sir, because the—OscarsSoWhite. Yeah, because our images are not projected, because the television tells us that we are not worthy of support. I would imagine that a young child, who doesn’t have the emotional armor to defend him or herself against that, could be misled into believing that they are not worthy of support. Yes, sir, I understand why they would give up on themselves for that reason. I think it was one of the poorest, you know, examples—I mean, it was one of the most powerful examples of his poor interpretation of history and his failure to comprehend.

And he said something about assassinations led us into chaos. The point of assassinations was to disperse black communities, to make us scared, to make us afraid. In fact, some people weren’t even going to vote for Obama until his wife went on 60 Minutes and said, “Hey, he’s a black man. He could get killed walking across the street, stray bullet,” because we were afraid, many black people, that Obama himself might be assassinated. So, for him not to understand—and he does; he’s a real smart guy—not to understand the lethal political and deadening effect of assassinations on the collective will of black people, I think, was disingenuous, and it was a moment of poor interpretation of history for the masses. He’s usually a more reliable public intellectual when it comes to race, even if you disagree with him. But that was a pretty poor example.

AMY GOODMAN: Before we wrap up, I wanted to move even further, to 2015, to President Obama’s interview with Marc Maron on his podcast WTF last June. It was taped just two days after the Charleston murders.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: The legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, discrimination in almost every institution of our lives, you know, that casts a long shadow, and that’s still part of our DNA, that’s passed on. We’re not cured of it.

MARC MARON: Racism.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: Racism, we are not cured of, clearly. And it’s not just a matter of it not being polite to say [N-word] in public. That’s not the measure of whether racism still exists or not. It’s not just a matter of overt discrimination. We have—societies don’t overnight completely erase everything that happened 200 to 300 years prior.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s President Obama in this radio interview, WTF with Marc Maron, using the N-word. Michael Eric Dyson?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Yeah, it was provocative. That’s not the first time Obama used the N-word, but it’s the first time he used it publicly while he has been president. You know, if you read his book, Dreams from My Father, there’s plenty enough of citation of that word, used by Obama in citing it being used by others. But I think it was especially brave. I think it was provocative, deliberately so. And I think he understood that he was going to raise the hackles, but also awareness of people that just because you don’t go around, you know, slinging the N-word doesn’t mean that, hey, I’m A-OK and that what I’m doing is fine and acceptable, because racism has not only a kind of personal bias element, it has a structural element that has to be talked about and dealt with. And Obama’s insistence that we have not yet healed ourselves of racism, I think, was a worthy reminder to the nation.

AMY GOODMAN: So let me move away from President Obama for a minute to Hillary Clinton, your assessment of Bernie Sanders.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: But you wrote in The New Republic that Hillary Clinton could do more for black people than President Obama.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Yeah, I think in terms of—given the way America operates, that Hillary Clinton won’t be said to be hooking her people up, because she’s not black. She could put forth public—and she has to put forth public policies, if she’s going to satisfy black interests and black populations. Obama could really skirt the issue. He could do—you know, he could show up black, and that would be enough for a lot of people, the fact that he was there, that his symbolism was extraordinary. Hillary Clinton doesn’t have that symbolism that resonates for African-American people. Yes, as the first female president, potentially that would, but not in terms of race. So what does she have to do? And she doesn’t have her husband’s ability to go in and charm the black masses, even though, as I argue in my book, as charming a racial alchemist as Clinton was, he was wan and disposable when he made those very questionable racial comments in South Carolina the first time Hillary Clinton was running, when he said about Jesse, “Well, Jesse Jackson won South Carolina twice.” In other words, that’s the black vote, black people get supported here, but that doesn’t mean you’re going to become president.

So, Hillary Clinton has no other recourse, if she’s going to win over black people, than to offer credible public policies that will address their interests. White privilege permits her to more forthrightly and explicitly articulate race as the basis for a particular policy than does Barack Obama. I’m not suggesting that she has more racial interest or more racial knowledge than Barack Obama. I’m suggesting that the way America operates with white privilege, she has the ability to do so publicly without being called to account for it.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you about Michelle Alexander’s post on Facebook, who wrote The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the [Age] of Colorblindness.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: She writes, “If anyone doubts that the mainstream media fails to tell the truth about our political system (and its true winners and losers), the spectacle of large majorities of black folks supporting Hillary Clinton in the primary races ought to be proof enough.” She said, “I can’t believe Hillary would be coasting into the primaries with her current margin of black support if most people knew how much damage the Clintons have done—the millions of families that were destroyed the last time they were in the White House thanks to their boastful embrace of the mass incarceration machine and their total capitulation to the right-wing narrative on race, crime, welfare and taxes.” That’s Professor Michelle Alexander.

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, as always, she’s brilliant, insightful, prescient even, and absolutely right. But again, you know, some people have made that argument for Barack Obama. Not sure she posted on Obama that way, not sure if she pushed back on the president explicitly, because even Michelle Alexander, as great as she is and as prophetic as she is, also has to acknowledge limits, boundaries and borders. And if we’re going to be brave about Hillary Clinton, which—who should be called to account, for sure, although she was not the president—Bill Clinton was the president. She did support many of the policies that were problematic. In my piece, I talk about my skepticism and approaching her and engaging her on those issues.

So I think Michelle Alexander is right. The question is: Does Michelle Alexander have a comparable argument about the president who’s in office now? Does she believe that he’s done the kind of damage, symbolically speaking, by lecturing black people, by refusing to put forth public policies, when unprecedented levels of black unemployment were raging? I have a long section in my book where I examine Obama’s claim that, “Hey, under my presidency, like most other Americans, black people are doing better.” Well, that really ain’t so, sir. So let’s do the numbers on that. And it would be interesting to see Professor Alexander weigh in on that.

AMY GOODMAN: But what about what you found?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, I mean, in every measurable category, black people are not doing well under Obama, not as well as the White House would have us believe. And some of that stuff is structural beyond his bully pulpit, but his bully pulpit has not helped us in terms of not speaking about these issues of race more forthrightly.

And secondly, I talk in my book about some of his racial philosophy—strategic inadvertence: “I’m not going to specifically speak about race, but these policies will have the consequence of helping racial issues”—of the heroic explicit and the noble implicit. So he’ll be explicit about assaulting black people, or at least criticizing them, but very implicit when it comes to white brothers and sisters. So, when you look at that, his own Department of Justice did an extraordinary job, I think, under Eric Holder, in regard to racial issues in America. And the housing unit has now caught up, in a sense, because they put forth an argument, that the Supreme Court recently upheld, that says it doesn’t have to be the intent to discriminate that will determine if discrimination is present and has to be held—and people have to be held accountable. But beyond that, his strategic inadvertence has discouraged the explicit embrace of race. And as a result of that, certain public policies that could be put in place have not been put in place.

I would love to see the brilliant Michelle Alexander weigh in on that. She’s right in what she says about Clinton. The question is: What choices do we have? We could say Bernie Sanders, and for many people, Bernie Sanders represents that interest. But part of the left’s problem has been that it believes when we solve the issue of class, we’ll solve the issue of race. And Bernie Sanders is a 74-year-old white man. He is to be commended for grappling with this issue and having a steep learning curve and catching up to some of these issues, as does 69-year-old white woman Hillary Clinton. But the reality is, is that to say that it’s about class and not race, well, Jackie Robinson was rich, Joe Louis was rich, but they weren’t treated any differently than any other black person in terms of Jim Crow law.

So, you know, I’m reminded of a story Derrick Bell told, the late great Derrick Bell, when we were lecturing together. He said, you know, some communists went to Harlem and said, “You know, hey, you need to join the revolution, and we need to change and transform.” And he said, the black man asked him, after he gave his spiel, he said, “Let me ask you a question: After the revolution comes, are you still going to be white? Oh, OK.” So, it’s not to suggest that communists have less racists than the Republicans. I think that is the case. I think socialists are less inclined to be racially driven than those who are right-wingers. But it does suggest, as well, that you can’t merely dismiss the legitimacy of a focus on race by embracing class. It’s both-and, not either-or. And I think both of these political figures need to catch up to that.

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s recent remonstration against Bernie Sanders vis-à-vis the issue of reparations was instructive here, not necessarily whether one supports reparations or not, but the point Coates made was: Here you are, as a socialist, in America, which is outside the pale, saying that, “Oh, no, I can’t deal with reparations. That’s a little bit too controversial, and that’s a little bit too outside the pale.” And he’s like, “Dude, you’re a socialist, in America, running for president! That’s beyond the pale there.” So those kind of interesting conundrums need to be addressed, and I would love to have the brilliance of Michelle Alexander on that, because at the end of the day, what is the choice? Is she suggesting that we support Bernie Sanders? Then, that would be, I think, a legitimate and tenable outcome of her criticism, but I’d like to hear more from her on that.

AMY GOODMAN: As we wrap up, what most surprised you in writing The Black Presidency?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: Well, you know, in studying this figure, Obama, he’s an extraordinarily exquisite, remarkable human being who’s put in a—you know, I’m reminded of Martin Luther King Jr.'s argument quoting Reinhold Niebuhr: “The battering rams of historical necessity” have thrust me into this position. There are a lot of policies I make quite clear that I disagree with on Obama. I disagree with—and this book is focused on race, so that's what I pay attention to. But I’ll tell you this. Some of the most famous critics of Obama, including my dear friend and mentor, Professor Cornel West, that I find Obama, when, you know, all of those legitimate criticisms—and some who are—some are illegitimate and bitter—that he’s much more humble than many of his critics, you know. And Professor West has made a career of—as a self-designated prophet full of humility. But I have found, ironically enough, that Obama’s humility is much more thorough and grounded than many of the other critics who have assaulted him. That doesn’t mean, therefore, that the criticisms are not legitimate. It’s the fact that I discovered him to be remarkably unimpressed, in the right way, with the power of that office, even as he seeks to figure out a balance between his historic community and his tribe and the broader society he must serve. Despite my sometimes consistent and fierce criticism of him, as a human being, I think he’s an extraordinarily decent man.

AMY GOODMAN: What would you like to see him do in these last months in office?

MICHAEL ERIC DYSON: I mean, get free, tell the truth as best you know it. And, you know, in the last State of the Union, could he not have mentioned Black Lives Matter? You’ve praised them before international associations of police chiefs. My god! You’ve brought them to the White House. And you’ve talked to them and engaged them. You don’t have to agree with everything they do; I don’t, either. But support and love and nurture these young people and encourage them. Might you not have mentioned to the nation, in your last speech as the spokesperson for American democracy, what they say makes a difference and it matters? So those kinds of things—giving signals, using the bully pulpit, strengthen public policies. You know, you’re doing all these executive orders. Then continue to do so. The other day, he made an executive order and said that these young people will not be put in solitary confinement. Continue to do that, and be open and honest about the vitriol that persists and your ability, with the time remaining, to speak to that. And perhaps your most effective use of your bully pulpit will be to tell the truth to the American people in a way, now that you’ve earned the trust and you’ve been there for seven-and-a-half, nearly, you know, seven-and-what? one-quarter of a year—tell the truth with the time remaining, so that that might prepare the way for the next president.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Michael Eric Dyson, I want to thank you for being with us, Georgetown University professor, political analyst, author of 17 books. His most recent is just out; it’s called The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Media Options