Guests

- Dave Zirinsports editor for The Nation magazine. His recent article is called “ ‘I Just Wanted to Be Free’: The Radical Reverberations of Muhammad Ali.” He’s the author of the Ali-themed book, What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States. He is also the host of Edge of Sports podcast.

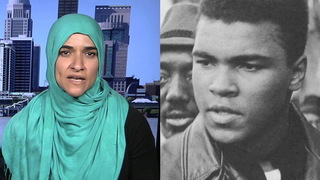

Dave Zirin, sports editor for The Nation magazine, joins us from Muhammad Ali’s hometown, Louisville, Kentucky, where he will attend Ali’s funeral. Zirin recounts Ali’s activism against racism in the city and says, “[T]his funeral is, in so many respects, Muhammad Ali’s last act of resistance, because what he is doing is pushing the country to come together to honor the most famous Muslim in the world at a time when a presidential candidate is running on a program of abject bigotry against the Muslim people, and the other presidential candidate is somebody who has proudly stood with the wars in the Middle East.” Zirin’s recent article in The Nation is called “'I Just Wanted to Be Free': The Radical Reverberations of Muhammad Ali.” He’s the author of the Ali-themed book, “What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: “Morning Has Broken” by Yusuf Islam, the artist formerly known as Cat Stevens. Yusuf Islam was one of the pallbearers at Muhammad Ali’s Jenazah, the traditional Islamic prayer service, the funeral that was held yesterday. Today, the interfaith service. Dave Zirin is in Louisville, along with Dalia Mogahed. Dave Zirin is a sports editor for The Nation. His recent article, “'I Just Wanted to Be Free': The Radical Reverberations of Muhammad Ali.” Among his books, What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States.

Dave, you are in—you’re in Louisville right now. You’re going to the funeral. Talk about what you feel is most important for people to understand about Muhammad Ali.

DAVE ZIRIN: Well, it’s stunning to be in Louisville. And Louisville is, in so many respects, a microcosm of the Muhammad Ali story globally, because Louisville is a place that Muhammad Ali protested in life. He went to fair housing protests. He said, “My people in Louisville are being treated like dogs.” The City Council of Louisville voted to renounce him as a citizen of Louisville. And yet, as recently as—actually, just a couple of years after they renounced his name, they named one of the main boulevards in Louisville Muhammad Ali Boulevard. And when I landed in the airport yesterday, there’s a huge sign welcoming folks to Muhammad Ali’s funeral. The buses say “Goodbye to the greatest,” “Goodbye to the champ.” There are commemorations all over the place.

And I really do believe, to echo Dalia’s comments, that this funeral is, in so many respects, Muhammad Ali’s last act of resistance, because what he is doing is pushing the country to come together to honor the most famous Muslim in the world at a time when a presidential candidate is running on a program of abject bigotry against the Muslim people, and the other presidential candidate is somebody who has proudly stood with the wars in the Middle East and the suppression of Palestinian rights. And amidst all of that, presidents, heads of states, leaders—everybody, including Donald Trump, has to tip their hat and respect Muhammad Ali. And there is something beautiful about that. And what it shows is that Muhammad Ali could not be broken. They tried, but they couldn’t break him.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to an article by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the six-time NBA champ and fellow convert to Islam. His article for Time.com is called “Muhammad Ali Became a Big Brother to Me—and to All African-Americans.” In it, he writes, quote, “As the draft extended to include more white, middle-class boys, opposition to the war grew in popularity. But despite our passion, we few athletes were unable to do anything significant to fight the draft. We left feeling powerless, especially knowing that had Muhammad allowed himself to be drafted, he would have never faced combat and would have still earned his millions. Instead, he would face the punishment for his convictions alone. That’s when I realized he wasn’t just my big brother, but a big brother to all African Americans. He willingly stood up for us whenever and wherever bigotry or injustice arose, without regard for the personal cost. He was like an American version of the comic-book hero Black Panther.” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, those are his words. Dave Zirin?

DAVE ZIRIN: Yeah, Muhammad Ali is the famous most—Muhammad Ali is the most famous draft resister in the history of war. And that’s something they’ll never be able to take away. One of the whitewashings that’s taken place since his death is that commentators just say, “Muhammad Ali was for peace,” “Muhammad Ali was against war.” But it was actually far more radical than that. Muhammad Ali was against empire. Muhammad Ali believed in solidarity with the black, brown and poor people of the United States, with the poor people of Vietnam and the people who were being killed in Vietnam. As Dalia was saying to me before we came on the air, Muhammad Ali saw a commonality between the death of Emmett Till and the young people in Vietnam. And that seared itself into his brain, this idea that he could not support a society that he viewed as uniquely brutal. And Kareem is absolutely correct: If Muhammad Ali had decided to agree to go in the draft, he would not have been in Southeast Asia with a gun in his hand; he just would have been asked to be a symbol in favor of the war. And even that was too much for him.

And it also has to be mentioned that Muhammad Ali, what he did was he gave a very young, very white middle-class antiwar movement confidence, and he gave young black civil rights activists the confidence to come out against the war. I spoke to Dorie Ladner from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee just the other night, and she said to me, “Those of us in SNCC, we were all against the war. But what Muhammad Ali did was he cleared the space for us to stand up and connect the war at home with the war abroad.”

AMY GOODMAN: Dave Zirin, this might be total apostasy, but might Muhammad Ali be the best argument against boxing ever?

DAVE ZIRIN: Well, it’s such an interesting argument, because it’s also true that if it wasn’t for boxing, we may never have known who Muhammad Ali was. And that’s one of the great contradictions of our society and also the opportunities that are often available to working-class black families. But yes, in so many respects, Muhammad Ali represents not just the brutality of boxing and the tragedy of boxing and what it does to people, but he also represents the way boxing always, whether we’re talking about Joe Louis, whether we’re talking about Sugar Ray Robinson, whether we’re talking about the great Jack Johnson—it’s always represented a symbolic morality play about the thwarted ambitions of black America and the ways in which boxing has often been a symbol, as Maya Angelou said of Joe Louis, a symbol of the way that we can have some form of justice and equality in our society.

AMY GOODMAN: Dave Zirin, the thoughts on who’s giving the eulogy, which I think is what Muhammad Ali wanted, but President Clinton, Billy Crystal, Bryant Gumbel?

DAVE ZIRIN: Well, first of all, Bryant Gumbel is one of the most lucid analysts of Muhammad Ali’s history. It’s Bryant Gumbel who said that Muhammad Ali allowed the black freedom struggle to move forward because he made people less afraid. Billy Crystal, a longtime friend of Muhammad Ali. I’ll be honest, the Bill Clinton, the presence there, it honestly—it does hurt, given Muhammad Ali’s historic place as a great figure against war and against bigotry, to have the person who signed the welfare bill, the person who signed the crime bill, the person who was in charge of the sanctions in Iraq—it will be painful to see him up there. But in many ways, in some respects, that is Muhammad Ali’s last victory. The same presidents that used to bug his phone and harass him and subject him to COINTELPRO now have to stand over his body.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there. Dave Zirin and Dalia Mogahed, I want to thank you so much for being with us. This does it for our show. They were speaking to us from Louisville.

I’ll be in Chicago Saturday, June 11, Jones College Prep at 3:00 for the 2016 Printers Row Literary Festival. That does it for the broadcast. We have two job openings at Democracy Now! Check them out.

Media Options