Guests

- Gideon Olivercivil rights attorney who represents Johanna Fernández.

- Johanna Fernándezprofessor of history at Baruch College in New York.

There has been a major break in the decade-long fight to unveil records related to the New York City Police Department’s surveillance of political organizations in the 1960s and 1970s. In recent years, the NYPD has come under fire for spying on Muslim communities and the Occupy Wall Street movement. But decades ago, the NYPD spied extensively on political organizations, including the Young Lords, a radical group founded by Puerto Ricans modeled on the Black Panther Party. The Young Lords staged their first action in July 1969 in an effort to force the City of New York to increase garbage pickups in East Harlem. They would go on to inspire activists around the country as they occupied churches and hospitals in an attempt to open the spaces to community projects. Among their leaders was Democracy Now! co-host Juan González. We speak with Baruch College professor Johanna Fernández, who has fought for a decade to obtain records related to the NYPD’s surveillance of the group. Last month, the city claimed it had lost the records. But this week its municipal archive said it had found more than 520 boxes, or about 1.1 million pages, apparently containing the complete remaining records. We’re also joined by Fernández’s attorney, Gideon Oliver.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: There’s been a major break in the decade-long fight to unveil records related to the New York City Police Department’s surveillance of political organizations in the 1960s and 1970s. In recent years, the NYPD has come under fire for spying on Muslim communities and the Occupy Wall Street movement. But decades ago, the NYPD also spied extensively on political organizations, including the Young Lords, a radical group founded by Puerto Ricans modeled on the Black Panther Party. The Young Lords staged our first action in July of 1969 in an effort to force the City of New York to increase garbage pickups in East Harlem. They would go on to inspire activists around the country as we occupied churches and hospitals in an attempt to open the spaces to community projects.

AMY GOODMAN: Among the leaders of the Young Lords, as you heard Juan going from “they” to “we,” was Juan González himself, a Democracy Now! co-host. Well, a professor here at Baruch College in New York City has fought for a decade to obtain records related to the New York Police Department’s surveillance of the Young Lords. Last month, a judge dismissed a lawsuit filed by professor Johanna Fernández after New York claimed it had lost the records. Questioned by a NY1 reporter, Lawrence Byrne, the NYPD’s deputy commissioner for legal matters, said the records seemed to have disappeared.

LAWRENCE BYRNE: It’s not at all unusual or nefarious that physical documents, old folders from the 1970s, have disappeared. But this goes back 45 years. It’s unfortunate. We’ll continue to search for it. But we haven’t been able to locate it.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But this week, Johanna Fernández received word from the city that the records had not been lost or destroyed. In fact, the city’s Municipal Archive had found more than 520 boxes—about 1.1 million pages—apparently containing the complete remaining records documenting the NYPD’s surveillance of political groups in New York City throughout the 1960s and the 1970s.

AMY GOODMAN: To talk more about this revelation, we’re joined by Johanna Fernández herself, history professor at Baruch College here in New York. She filed a lawsuit in 2014 to force the City of New York to locate and make public records on police surveillance of the Young Lords. Her forthcoming book is on the Young Lords, is called When the World was Their Stage. And we’re joined by her attorney, Gideon Oliver.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! So, Johanna, talk about how this all happened.

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: Well, I began this search a decade ago. And the Police Department in New York City gave me the runaround. And I personally believe that they were duplicitous about three years ago. I went in person to 1 Police Plaza thinking that perhaps I could rationally talk to somebody. And they suggested that they were going to help me find the records, and they called me “professor” and “doctor.” And then they sent me a letter like about six months later telling me that they were going to dismiss my request, my FOIL request. And it was then that I pulled resources together and hired Gideon Oliver, in part because I understood the historical significance of these records, not just for the Young Lords, but for the history of New York City and the history of activism, and the ways in which the police have systematically undermined and, essentially, destroyed radical organizations, such as the Young Lords.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Johanna, how does somebody lose and then suddenly find 500 boxes? I mean, where were these boxes? Where were they supposed to be, and how did they suddenly come up with them?

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: Well, in 1971, radical lawyers in New York filed a suit demanding that these files of police surveillance be preserved. And in 1986, a judge said that they could not be discarded, that they had to be preserved for the historical record. And the judge at that point said that the police had to work with the Municipal Archive of the City of New York to preserve these records. And from 1986 to the present, they’ve been lost, over a million records. But they were found. One day they were lost, and now they were found. Now they are found, thankfully, in the—in what is known as the Queens warehouse, which houses currently not just the Handschu boxes—again, an epic find—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And Handschu was the original case that you were referring to.

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: The Handschu was the original case I was referring to, which is an epic win for civil liberties and for historians seeking to understand the history of the city. But they—but this warehouse apparently houses over 10,000 boxes of records of the City of New York that have not been inventoried. So that’s exactly where they were found.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to some of the New York City police index cards documenting surveillance of the Young Lords, including a number of these index cards on you, Juan. One dated April 4th, 1969, describes Juan’s height and weight—5’11”, 150 pounds—and reads, quote—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I wish I was at that weight now.

AMY GOODMAN: “The above person”—this is what it says—”The above person was observed at a rally held at 110 St. and B’way. Sponsored by the West Side Community Council, against urban renewal, and Columbia expanision [sic]. He did not speak,” unquote. Another dated January 18, 1970, reads, quote, “The above named person was present at the first Spanish Methodist Church on 111 St. & Lex. Ave. Manhattan. He along with a group of Young Lords and other sympathizers were at the church to feed the community children and give them clothes,” unquote. There are detailed notes not only on Juan’s participation in the protests, but also on his published articles and media appearances. Your response to this, Juan?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, what I—

AMY GOODMAN: Is it true, first of all? Did you not speak at 110th and Broadway?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, yeah, I’m sure that there were many times when I did not speak—a surprise to many. But the—what I’m interested in is: Who was giving the reports? Because we’ve always had—we’ve always had debates among former Young Lords about who were the police undercovers. And, of course, while I’m sure that these files would have those names redacted, we could pretty much be able to piece together by when the events occurred and who we recall being there as who would be the likely informants. But it is a—it is an amazing fact, because, back then, the group—we knew it as BOSS, Bureau of Special Services, or the “Red Squad,” that was the one that was in charge of collecting all of this information. And it was a very extensive organization with lots of informants that were providing reports.

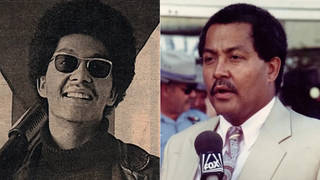

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Juan, I want to play a clip of you from the Third World Newsreel film El Pueblo se Levanta: The People Are Rising.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The main thing that we’re clear on is that it’s such a simple thing to give us space. And now that we’ve gotten into this church and eaten here and been here for hours, we know what a big place it is—incredible space in the church, all unused, you know, never open to the community. And it’s just incredible to us how such a simple thing like granting us space has resulted in so many heads being busted and so much trouble in East Harlem.

And our only understanding of that has to be that religion, you know, organized religion, has so enslaved our people, has so destroyed their minds to thinking about salvation in the hereafter, they refuse to deal with the conditions that they have now and with the oppression that they have now. The people who come to this church are mostly Puerto Ricans who have already raised themselves to certain standards. Many of them have left the community. They no longer relate to the community except to drive in on Sundays and go to services.

And it’s amazing to us how people can talk about, you know, Jesus, who walked among the poor, the poorest and most oppressed, the prostitutes, the drug addicts of his time, that these people can claim to be Christians—right?—and they’ve forgotten that it was Jesus who said that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. And they forget that it was Jesus who said the last shall be first, and the first shall be last. And they forget that it was Jesus who said feed the hungry and clothe the poor. And this is what we’re after. We’re after following the tenets and the spirit of Christianity, not the letter of Christianity, of those Bibles that have perverted Jesus’s real revolutionary and social consciousness.

AMY GOODMAN: And that was Juan González. Thanks to the Third World Newsreel for that clip. And for our listeners, if you want to see a young Juan González, go to our website at democracynow.org. The significance, Gideon Oliver, of these documents that have been found in Queens?

GIDEON OLIVER: Can’t be understated. I mean, this is the entire trove of records of the NYPD’s political surveillance operations between 1955 and 1972. So we’re talking about not just records of surveillance of the Young Lords and Juan, but also of surveillance of the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, the antiwar movement in New York City. And it was a part of the benefit of the bargain of the settlement in the Handschu litigation that these documents would be preserved, or if they were to be destroyed, they would only be destroyed after a process, a sign-off process that the Law Department and the Municipal Archive would have to participate in. So, the fact that these documents not only have now been discovered, but can be made available to the public, is just extraordinary.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, but now there’s going to have to be some kind of a cataloging process, right? I mean, because you’re talking about documents that have not even been properly organized. Are you marshaling a group of folks to do that? Or what—how is this going to work?

GIDEON OLIVER: That’s not my end.

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: So, I think it’s important to say that the Municipal Archive of the City of New York is committed to making this available to the public and to working with scholars. And they’ve invited me, early on, to look through the records and to help identify the most important records for my project, but also to help in the process of inventorying this really epic trove of documents, which will help historians understand the hard hat demonstrations, for example. There is a whole section—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Famous Whitehall demonstrations, yes.

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: Exactly. So there’s a whole section on that. There is an entire section of boxes on the Columbia strike of 1968, but also activities at Columbia in 1972. The Black Panther Party is identified by name and is one of the only organizations that is identified fully by name, along with the NOI. I imagine that there is information here about the murder of Malcolm X. And so, these records are really going to transform our understanding and critique of the parameters of allowable conduct on the part of the police. And we know that there has been a lot of debate and discussion about what the police can and cannot do in American society today in the aftermath of 9/11, but the historical record really allows us to step back and ask questions about civil, constitutional rights.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re talking about local surveillance. What about federal surveillance, like COINTELPRO, not that they didn’t also work with the local police, but the Counterintelligence Program of the FBI?

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: So, there was an enormous amount of surveillance on the part of the FBI, the COINTELPRO project of the FBI, which, as we know, was responsible in working with the Chicago police in the assassination of Fred Hampton in Chicago in 1969, right around the time that the Young Lords were in fact about to occupy the First Spanish Methodist Church. What I found in my research, because I requested the COINTELPRO documents pretty early on, at the same time that I requested the police documents, is that the police documents are a lot more methodical and a lot more specific. And it makes sense, because the police is close to local communities. And this is not just about New York, but it was police departments across the nation that were engaged in disrupting and surveilling—violently, in many instances—the work of activists. And those records are more revelatory, I believe, from my study of collections of both, than the COINTELPRO documents.

AMY GOODMAN: Did police, Juan, ever approach you and say afterwards—you know, maybe someone you became friendly with—that they were monitoring you and following you?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Oh, yeah, well, there were former—yeah, there were former policemen, who afterwards, you know, clearly said to me, “Yeah, we were involved in following you.” And also, for instance, in 1972, I was arrested by 13 FBI agents and the police on Selective Service violation. But they not only—they not only busted into our headquarters on 142nd and Willis Avenue in the Bronx, they broke down the doors, they ransacked the entire office and took all of our records. And then, when we went to court to say, “Hey, we want our records back,” they denied that they ever had them. And so, I’d be interested to see if there are reports in there—

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: If they’re there.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —about what they found when they ransacked our offices and then swore before a judge that they didn’t take anything. So, it would be interesting to see that.

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: And whether they kept them. Right?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Right. Well, I’m sure they did.

JOHANNA FERNÁNDEZ: Maybe they’re there.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: They definitely kept what they found, because we never got it back. But—

AMY GOODMAN: And, Juan, your thoughts today on all of these documents? I mean, a number of these documents involve you that are being released.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, you know, it’s—I think it’s great that they’ve been found. And as you said, it’s going to be a treasure trove for the historians to go back and recreate the history. The problem with these abuses is that it always takes decades to uncover them. And in the meanwhile, the damage has been done to the activists and the dissidents that were involved in these movements. And it’s almost as if the society never learns, that the abuses just keep on being repeated a generation or two generations later. And so that’s the big problem that I have with the continuing government abuse of the way that they look at dissidents.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, Gideon Oliver, we do have to wrap up, but this whole issue of Handschu, what this agreement was—you just have a minute—and whether we know whether this surveillance is continuing?

GIDEON OLIVER: Well, certainly, political surveillance by the NYPD is alive and well in New York City, and in the Handschu context, Judge Haight is still on the case. He’s been on the case for many years. And he is in the process of considering whether the proposed settlement in the Muslim spying cases should be adopted by the court. And I think that debates like that are really—have been really shortchanged for the lack of these documents. And in the future, hopefully, the availability of these documents will enrich those debates.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you both for being with us, Gideon Oliver, attorney, Johanna Fernández, for your persistence in getting these documents and, ultimately, a million of these documents being found. Johanna Fernández is professor of history at Baruch College. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. When we come back, stay with us.

Media Options