Guests

- Trevor Timmexecutive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation and a columnist for The Guardian.

- Bradley Mossnational security attorney who has represented whistleblowers.

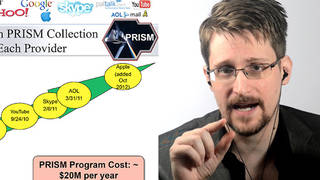

It has been three years since National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden released classified NSA files to media outlets that exposed global mass surveillance operations by the U.S. and British governments. If he returned to the United States from Russia, where he now lives in exile, he would face charges of theft of state secrets and violating the Espionage Act, and face at least 30 years in prison. This week his supporters launched a new call for President Obama to offer Snowden clemency, a plea agreement or a pardon before the end of his term. We host a debate about whether Snowden should be pardoned with Trevor Timm, executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, and Bradley Moss, a national security attorney who has represented whistleblowers.

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: It’s been three years since National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden released classified NSA files to media outlets that exposed global mass surveillance operations by the U.S. and British governments. He is now charged with theft of state secrets and violating the Espionage Act, for which he faces at least 30 years in prison. He currently lives in political exile in Russia.

This week, Snowden’s supporters launched a new call for President Obama to offer Snowden clemency, a plea agreement or a pardon before the end of his term. Today we look at how the new campaign has reignited a debate over what punishment, if any, Snowden should face. At an event in New York City on Wednesday, the ACLU, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International called for Snowden to be pardoned. This is the ACLU’s Ben Wizner, Snowden’s attorney.

BEN WIZNER: With respect to the question about whether we’re applying to the Department of Justice, respectfully, the Constitution assigns this authority to the president, not to a lawyer in the Department of Justice. And it does so for a reason: because the pardon power is quintessentially a political power. It’s about when a president decides that there are overriding national reasons not to enforce the law as written. In a run-of-the-mill case, it might make sense to set up a bureaucracy to handle those kinds of requests. I don’t think I need to say this is not a run-of-the-mill case. And this is one that has serious geopolitical consequences. And so this campaign is directed only at one person, and that person is the president.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: That’s the ACLU’s Ben Wizner speaking Wednesday. On the same day, The Guardian published about 20 statements on the case from prominent figures, including professors Noam Chomsky and Cornel West, Black Lives Matter activists, and politicians. Among them was former Democratic presidential challenger Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who argued Snowden educated the public about how the NSA’s mass surveillance program violated their constitutional rights. Sanders called for a resolution to the case that acknowledged Snowden’s troubling revelations should, quote, “spare him a long prison sentence or permanent exile.”

AMY GOODMAN: The Guardian also published comments from those who do not defend Snowden. Former NSA Director Michael Hayden said Snowden should face, quote, “the full force of the law” if he returns to the United States. Former NSA counsel Stewart Baker wrote that Snowden’s leak caused harm to U.S. national interests.

Meanwhile, Edward Snowden himself spoke out on Wednesday in a press conference, where he and others announced a Pardon Snowden petition. Snowden spoke by video stream from Moscow.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: While I am grateful for the support given to my case, this really isn’t about me. It’s about us. It’s about our right to dissent. It’s about the kind of country we want to have, the kind of world that we want to build. It’s about the kind of tomorrow that we want to see, a tomorrow where the public has a say.

History reminds us that governments always experience periods in which their powers are abused, for different reasons. This is why our founding fathers, in their wisdom, sought to construct a system of checks and balances. Whistleblowers, acting in the public interest, often at great risk to themselves, are another check on those abuses of power, especially through their collaboration with journalists.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: That was Edward Snowden speaking Wednesday via video stream from Russia. Well, in 2013, while Snowden’s whereabouts were still undisclosed, Donald Trump called for Snowden’s execution during an interview on Fox & Friends.

DONALD TRUMP: Spies, in the old days, used to be executed. This guy is becoming a hero in some circles. Now, I will say, with the passage of time, even people that were sort of liking him and maybe trying to go on his side are maybe dropping out. But, you know, when you look at where he goes—and now nobody knows where he is. But we have to get him back, and we have to get him back fast. They’re talking about it could take years, it could take months, but maybe years. That would be pathetic. … This guy is a bad guy. And, you know, there is still a thing called execution. You really have to—you have to take a strong hand. You have thousands of people with access to kind of material like this. We’re not going to have a country any longer.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, the new push to pardon Edward Snowden comes as the Hollywood version of his story opens in theaters this week. On Wednesday, we interviewed Snowden director Oliver Stone and actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt, who plays Snowden in the film.

Today we host a debate about whether Snowden should be pardoned. Joining us here in New York is Trevor Timm, executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation and a columnist at The Guardian. In Washington, D.C., we’re joined by Bradley Moss, national security attorney who’s represented whistleblowers as well as people from the intelligence community.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Trevor Timm, why do you think that Edward Snowden should be pardoned?

TREVOR TIMM: Well, quite simply, Edward Snowden is the most important whistleblower we have seen in at least a generation. You know, when you think about what has happened since he first came forward three-and-a-half years ago, a federal appeals court has ruled the NSA’s mass surveillance programs illegal. Congress has passed the most—or the first intelligence reform in 40 years. And there has been a sea change in public opinion on privacy online. And then we have seen, of course, the tech companies, on the private side, instead of collaborating with the NSA, which Edward Snowden also revealed, have now turned and are implementing all sorts of security and encryption features that protect people’s privacy and security, and prevent this mass—this type of mass surveillance from happening in the first place.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Bradley Moss, your response? Do you think Snowden should be pardoned?

BRADLEY MOSS: No, sadly and unfortunately for Mr. Snowden, I do not at all. You know, Trevor and a lot of Mr. Snowden’s advocates do a very good job of focusing on the small number of domestic issues that Edward Snowden revealed—Section 215, which was the telephone data program, Section 702, which was the internet data collection—but they largely omit or gloss over everything else that Mr. Snowden leaked. He leaked how the NSA spies on Chinese government and how it was spying on certain Chinese companies that had ties to the Chinese military. They overlook how he exposed what is called operation MYSTIC, which was spying operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. They overlook how he exposed the technical details of a specific spy ship, a spy vessel, that was working in various parts of the world to intercept data. The idea of pardoning someone whose leaks went far beyond anything of American civil liberties, and was exposing the basic elements of signals intelligence—which is what NSA is supposed to do, that’s their job—the idea of pardoning someone in that circumstance is, as far as I’m concerned, ludicrous.

AMY GOODMAN: Trevor Timm?

TREVOR TIMM: Well, so, a couple things here. One, I think we have to realize that the amount of documents that Snowden released himself is zero. He gave these documents to some of the most respected journalists in the country, at some of the most well-known papers, which, by the way, ended up winning Pulitzer Prizes for their stories. And it was these journalists who decided what was in the public interest and what may have affected national security, and actually consulted with government officials before publishing these stories. And the government was allowed to make objections.

But beyond that, I think we have to, you know, think about this as a global issue. It’s not just the United States and American citizens that deserve privacy rights. You know, these mass surveillance systems that are happening around the globe, I think, are a cause for alarm for literally billions of people. And, you know, what Snowden critics don’t bring up a lot of times is that actually the Obama administration changed the rules for its global spying network, too, because of these stories. There was executive rules that have now been tightened also because of the Snowden revelations. So, certainly, the domestic spying revelations had the biggest impact, but I don’t think we should discount the other stories that were published by journalists at The Washington Post and The Guardian.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Bradley Moss, do you agree with that? Do you think there have been some beneficial effects of Snowden’s revelations?

BRADLEY MOSS: Well, I’ll give him credit that there was some tightening of how things were run, particularly in terms of the domestic side, particularly in terms of things like data—sorry, the telephone data program and the USA Freedom Act that was passed. I’ll give him credit for that. In fact, as far as I’m concerned, if DOJ were to ever get this to a trial, I wouldn’t even bother bringing up those leaks, because they’re irrelevant—I mean, they would just muddy the water.

But what Trevor gets into here—and I’ve heard this argument a lot of times—is, OK, first they say Snowden didn’t actually publish anything. It’s irrelevant as far as the law is concerned. The law doesn’t care whether or not he published a document. He was authorized for access to classified information, he removed it from the secure location in which it was supposed to be, and he gave it to unauthorized individuals—namely, the journalists like Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras and Barton Gellman. None of those three individuals, for all of their credentials and qualifications, none of them had been vetted by the U.S. government for access to classified information. I hold a security clearance due to the nature of some of my clients’ classified affiliation with the U.S. government. I had to go through the vetting. There’s approximately 4 million people who also hold clearances. It is a sacred trust. And Snowden broke it by giving these documents to people who were not authorized to have it.

And in terms of the other point that Trevor has made, that certain restrictions or certain limitations were now placed on how spying was done on individuals overseas, if he—if Mr. Snowden believed that that should be reined in—and that’s not a legality issue, that’s a policy or a moral question—if he thought that Congress was not fully aware of the extent of it, those are things he could have brought to Congress. He could have gone to the intelligence committees. He could have gone to individual senators or members of Congress. I’m sure Senator Rand Paul would have been more than willing to have heard information about this. But that is Congress’s job from a purpose of oversight. We live in a republican—small R—a republican form of government, where we elect people to both serve us in the legislature to oversee the executive branch, and in which we elect a president and a vice president to implement the laws passed by Congress. By doing what he did, Mr. Snowden circumvented all of that and said, “I don’t care what any of you have already—excuse me—I don’t care what any of you have already decided; I’m going to shame you into changing it.”

AMY GOODMAN: Trevor Timm, what about that—Snowden could have gone up either the chain of command where he worked or gone to Congress?

TREVOR TIMM: You know, this is a common thing that Snowden critics often say, and it’s actually pretty ridiculous. You know, first of all, Snowden was a contractor, so a lot of the whistleblower protections that exist wouldn’t have applied to him. But there’s actually a much larger issue here. You know, this wasn’t some rogue NSA agent that he was trying to expose or some program that only a handful people knew about. This was authorized, the mass surveillance program which collected every single phone call of every single American—this was authorized at the highest levels of government, by the executive branch, by the secret FISA court. And Snowden would have essentially been going to his superiors to tell them that what they were doing was illegal and unconstitutional. And it’s ridiculous to think that they would have responded in any way beyond casting more suspicion on him. You know, in fact, there was high-level NSA officials that had tried to go to the heads of the NSA before about this very same program and were rebuffed. And so, the only aspect—the only option that he had was to go to the press.

AMY GOODMAN: We’ll talk more about that in a minute. We’re going to break, then come back to Trevor Timm, who is executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, columnist at The Guardian, and, joining us in Washington, Bradley Moss, national security attorney. We’ll be back with both in a minute.

Media Options