Guests

- Ramzi Kassemprofessor of law at the City University of New York School of Law, where he directs the Immigrant & Non-CItizen Rights Clinic.

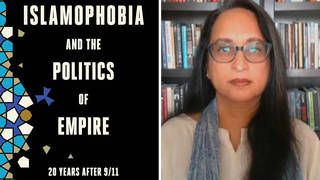

- Nazia Kaziprofessor of anthropology at Stockton University. Her latest article for The Chronicle of Higher Education is “Teaching Against Islamophobia in the Age of Terror.”

- Debbie Almontaserpresident of the Muslim Community Network. She was forced out of her position in August 2007 as the founding principal of the Khalil Gibran International Academy. In 2010, the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ruled that the New York City Department of Education discriminated against her “on account of her race, religion and national origin.”

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump responded to the weekend attacks by lashing out at Muslim immigrants and refugees, calling them a “cancer from within,” while Democrat Hillary Clinton said Trump is helping ISIS to recruit more fighters. South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham called for the New York bombing suspect, Ahmad Khan Rahami, to be treated as an “enemy combatant” rather than be treated as a civilian suspect. “The idea that they should all be collectively punished … is, frankly, racist. And that’s what we should call it,” says lawyer Ramzi Kassem with clients held in Guantánamo. “The notion that we should generalize … military detention, extrajudicial imprisonment is not only absurd and runs against U.S. and international law, but it is the practice of totalitarian regimes.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re broadcasting from Chelsea, from New York City, that actually has just opened up in the last 12 hours on 23rd Street between Sixth and Seventh, where the bomb went off. The police, while there, have now opened the street, and TV crews and vans are all there continuing to film. We are having a roundtable discussion about the bombings in New York and the stabbing attack in Minnesota, the bombings in New Jersey, as well. And I want to return—to turn to the response of the major-party candidates, of Donald Trump, the Republican presidential nominee, who responded to the weekend attacks by lashing out at the Muslim immigrants and refugees, calling them “a cancer from within,” suggested American security forces should follow Israel’s example in racial profiling. He said this during an interview on Fox News.

DONALD TRUMP: We’re going to have to hit them much harder over there, and we’re going to have to find out—you know, our police are amazing. Our local police, they know who a lot of these people are. They’re afraid to do anything about it, because they don’t want to be accused of profiling, and they don’t want to be accused of all sorts of things. You know, in Israel, they profile. They’ve done an unbelievable job, as good as you can do. We’re trying to be so politically correct in our country, and this is only going to get worse. This isn’t going to get better. And what I said is, you have to stop them from coming into the country.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let me play Donald Trump, a little more of what he had to say, and Hillary Clinton’s reaction.

DONALD TRUMP: These attacks and many others were made possible because of our extremely open immigration system. From 9/11 to San Bernardino, we have seen how failures to screen who is entering the United States puts all of our citizens—everyone in this room—at danger.

HILLARY CLINTON: We know that a lot of the rhetoric we’ve heard from Donald Trump has been seized on by terrorists—in particular, ISIS—because they are looking to make this into a war against Islam.

AMY GOODMAN: Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump. South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham called for Ahmad Rahami to be treated as an “enemy combatant” and placed in indefinite military custody rather than be treated as a civilian suspect. It’s interesting. I heard a counterterrorism expert today on television saying that’s exactly what ISIS wants, to be treated as a military force—they have enemy combatants—and not to treat him simply as a criminal. Can you talk about this, Ramzi Kassem? What does this mean?

RAMZI KASSEM: Yeah, I mean, I think it’s really important to move past both sides of this conversation, as exemplified by Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Most of the conversation goes through the security lens, and so Donald Trump is arguing that Muslims are a threat to security, and Hillary Clinton is arguing that we shouldn’t discriminate against Muslims because that would endanger our security, as well. So, in other words, there’s this instrumental approach to Muslims, where we’re just a pawn in a larger security game, in a global security game. And so, I think we really have to move past that discourse. What we’re talking about are American Muslims, some who have been here for generations. Islam is not new to America. These people belong here. This is their home. The idea that they should all be collectively punished and Muslims in the future should be prevented from coming here because one Muslim happened to do something criminal is, frankly, racist. And that’s what we should call it, and it shouldn’t be debated as some kind of policy proposal. So I think that’s our starting point.

Then, when you move on to labels like enemy combatant and even the label of terrorism itself, these are labels that really impede understanding. They blind us to other possible understandings of these acts of violence, ranging from the personal to the political to the psychological. As long as we’re obsessing over who to call an enemy combatant, who to label a terrorist, we’re preventing ourselves from gaining a deeper understanding of whatever the phenomenon is. And actually, I should say “phenomena,” plural, because whatever drove that young man, if he did do it, in Minnesota to whatever he did is going to be different from what drove the individual here in Chelsea to plant these bombs. And so—and so, I think, really, our understanding, going to, you know, what Nazia was saying, we have very real blinders on in this country that are preventing us from gaining a real and meaningful understanding of what is happening domestically and what is happening internationally. As someone who’s represented Guantánamo prisoners for over a decade, I can tell you that the notion that we should generalize that practice, generalize these legal practices—military detention, extrajudicial imprisonment—is not only absurd and runs against U.S. and international law, but it is the practice of totalitarian regimes.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Nazia Kazi in Philadelphia at Stockton University, your response to what Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton had to say, and also on the point you’re making in your article “Teaching Against Islamophobia in the Age of Terror”?

NAZIA KAZI: Sure. So my response to both of these candidates responding to the events of this weekend, I mean, I think when we talk about immigration to the U.S., we need, in public discourse, a much wider conversation. I mean, if we’re talking about Somalis in Minnesota, we can’t fall back on these clichéd notions of immigrants coming here for a better life. We have to really ask about the conditions that lead to migration. And when we’re talking about Somalia, that means talking about U.S. military intervention, real political and economic policies that lead to this type of migration. So that’s absolutely critical.

And the other thing we need to be aware of in this moment is, any time things like this happen, we see this space opened up for Muslim Americans to represent themselves, to speak up. This roundtable might be an example of that. And usually what happens is one of two really tragic outcomes. One is that Muslims will repeatedly condemn ISIS. And two is that Muslim Americans will sort of wrap themselves in the American flag and position themselves as these quintessential patriots. And what happens when we engage in these type of conversations is a real diversion from the issues at hand, when we ought to be talking about the increasing role of militarization of daily life in the U.S. or the ramping up of our military apparatus abroad. And it is really the classroom that could become a space for this type of engagement.

AMY GOODMAN: Debbie Almontaser, you have been dealing in your own family with attacks on your family. You yourself aren’t now taking public transportation.

DEBBIE ALMONTASER: That’s been for the last couple of days, Amy, and it’s just, you know, being cautious, given that this attack took place right here in the city. And so, I made the decision, the conscious decision, not to travel in public transportation. But again, you know, yesterday, I was in the middle of the city in City—near City Hall. It was fine. Sometimes, you know, I have this sense to overreact, as well as others, and it’s justifiable and understandable. But we can’t live in fear. And this is something—this is something that I’m constantly telling members of my community, is that we can’t live in fear, that we’re part of this society, that we need to live our lives, and we need to be unapologetically Muslim and continue contributing to society, whether it’s in our professional field or in our communities, volunteering and doing things that we’ve been doing. And so, that’s one thing that’s really critical.

And I really appreciate what Nazia is talking about, because just today there was an op-ed that was published in the Gotham Gazette that I had actually written about using the classroom as a place for teachable moments and to make sure that we address racism and bigotry, and, given the number of hate crimes that have taken place locally and nationally, how important it is for teachers to establish a caring and nurturing environment where children could feel free to speak their minds and know that their fellow students are there to support them and that they’re allies and upstanders, versus being bystanders, when something happens in the school cafeteria or the schoolyard.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, it’s interesting, one of the things that have come out in the last 24 hours about Ahmad Khan Rahami is that years ago his sister filed a complaint with the police around domestic violence. And we’re finding this so much—now, she recanted that, but in a number of these cases—that the first signs are violence within the family, whether it’s Omar Mateen attacking his wife, who shot up the Pulse nightclub and led to so much pain and misery, that actually it is taking domestic violence seriously at the beginning that might be preventative.

DEBBIE ALMONTASER: It certainly is. And the thing that’s disturbing, Amy, is that what we see constantly is when we see that there are mental health issues that are brought up, immediately that narrative is changed. And so, for example, right here in New York City, I was very perturbed by the notion of some of our elected officials saying we’re not calling this a terrorist attack. Why aren’t we calling it a terrorist attack? It is a terrorist attack. When someone seeks to terrorize people by putting bombs anywhere, that is terrorism. And so, waiting and holding back on it, as if to say we’re waiting to see if it was a Muslim, therefore calling it a terrorist act, is really unfortunate, and it really puts American Muslims in a position that makes people wonder, “Is Islam inherent to violence and terrorism?” And that’s not the case. And it’s really important for us to work very hard in changing that narrative and changing the language. When something does happen, we have to call it what it is. Whether it’s a Christian, a Muslim, a Jew, anyone who does anything in the name of violence against people, we need to call it out.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask our guest in Philadelphia, Nazia Kazi, how you use the classroom to teach against Islamophobia.

NAZIA KAZI: Yes. This is kind of an evolving strategy as I develop ways to relate current events that are happening in real time to a classroom. And I think one of the things is to really regard these tragic events as teachable moments, as moments to really get our students to pause and deliberately reflect upon the nature of our—the world around us. A perfect example of this was last year when the Paris attacks happened. A really fruitful classroom conversation took place about why there was a Facebook solidarity filter with the French flag, but not one with the Lebanese flag. And that led to a really remarkable conversation about race and the value of white victims, really.

I also think that, as I said earlier, we need to inject critical thinking into the dialogue. We need to get away from sort of knee-jerk vengefulness—right?—and think very broadly about the U.S.’s role as an imperialist superpower. I mean, my students are surprised when they learn about, you know, everything from Iran-Contra to what you said at the top of the show about white phosphorus being supplied to Saudi Arabia. And these types of moments in the classroom really lead to a way more fruitful dialogue than just clichéd notions about Islam being a religion of peace or Muslims worshiping the same God as Christians and Jews. It leads to a far more fruitful conversation when we begin to think geopolitically.

AMY GOODMAN: Ramzi Kassem, final word?

RAMZI KASSEM: You know, my hope, again, in the coming week—and I’m sure my hope’s going to be dashed—is that this time lawmakers and policymakers won’t come out with harebrained proposals to reform our way our immigration laws are implemented and that this time law enforcement agencies like the FBI and the NYPD won’t descend on entire communities rather than conduct their work in a more targeted fashion. But again, I’m sure that my hope is going to be dashed. Time and again, every time something like this happens, be it in New York or overseas or elsewhere in the United States, there’s no shortage of people, dozens of people, who will come into our offices at CLEAR saying, for example, that they’re being approached for questioning by the FBI, even though they have no connection to what happened.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there. We’ll continue the conversation. I want to thank Ramzi Kassem, CUNY law professor; Nazia Kazi, who is at Stockton University; Debbie Almontaser, thanks so much for joining us. And I want to thank our guest in Philadelphia, Haji Yusuf. Thanks so much.

Media Options