Related

Guests

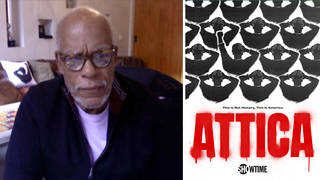

- Heather Ann Thompsonan American historian, author and activist. Her new book is Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. She is a professor of history at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

- David Rothenbergmember of the Attica observers’ committee. He was one of the 35 people brought into Attica to negotiate on behalf of prisoners. He is founder of The Fortune society.

Today prisoners in at least 24 states are set to participate in a nationally coordinated strike that comes on the 45th anniversary of the prison uprising at Attica. Much like the prisoners who took over New York’s infamous correctional facility in 1971, they are protesting long-term isolation, inadequate healthcare, overcrowding, violent attacks and slave labor. We speak with the author of an explosive new book about the four-day standoff, when unarmed prisoners held 39 prison guards hostage, that ended when armed state troopers raided the prison and shot indiscriminately more than 2,000 rounds of ammunition. In the end, 39 men would die, including 29 prisoners and 10 guards. We are also joined by David Rothenberg, who was a member of the Attica observers’ committee that was brought into Attica to negotiate on behalf of prisoners. He is founder of The Fortune Society.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, prisoners striking today say conditions are not much different from those that prompted the largest prison rebellion—one of the largest prison rebellions, 45 years ago at Attica. It was September 9, 1971, when state police raided the upstate New York prison, ending a protest against racism, officer beatings, rancid food, no rehabilitation programs and forced labor. For four days, the unarmed prisoners held 39 prison guards as hostages. On September 13th, then-New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered armed state troopers to raid the prison. Troopers then shot indiscriminately more than 2,000 rounds. In the end, 39 men would die, including 29 prisoners and 10 guards.

AMY GOODMAN: Before we’re joined by two guests, I want to turn to Attica prisoner Frank “Big Black” Smith. He died in 2004 at the age of 70. “Big Black,” as he was known, became a chief spokesperson of the prisoners during the uprising. In 2000, he and other prisoners won a $12 million agreement from the state of New York. During the uprising, he was forced to lie on a table while officers beat and burned him. He was also threatened with castration and death. This is an excerpt from the film Ghosts of Attica, a Lumiere production, made by Court TV, that features Frank “Big Black” Smith and the late Liz Fink, who served as the lead attorney for the former Attica prisoners. The first voice you hear is Big Black.

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: People laying all over, and they’re all bleeding and bloody and stuff. You know, so everybody know now that it’s real, that this is it. You know, they’re here now. They’re in the yard now. They got control.

ELIZABETH FINK: State troopers just took their clubs and beat them down the stairs, broke people’s legs, hit them on the tibia and broke tibias. On their back, on their head, in their genitals, on their front, you know, wherever they could hit them, that’s where they beat them.

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: I’m telling you, my name is being called: “Where is Big Black? Where is Big Black? Get up, Black! Get up!” And he’s busting me with a [N-word] stick, pickaxe, and got a .38 in his hand. And I gets up. And he—bam! In my side, in my back. And made me run with my hand on my head over to the side. And before I got over there, two, three more correction officers with him now, and everybody’s hitting me.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Attica prisoner Frank “Big Black” Smith. He became a chief spokesperson for the prisoners during the uprising.

For more on Attica and its legacy, we’re joined by two guests. David Rothenberg is with us, member of the Attica observers’ committee, one of the 35 people who was brought into Attica to negotiate on behalf of the prisoners. He went on to found The Fortune Society. And Heather Ann Thompson joins us, an American historian, author, activist, who has written an explosive new book. It’s called Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. She’s professor of history at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Her book opens with an epigraph from Attica correction officer Edward Cunningham. He says, quote, “You have read in the paper all these years of the My Lai Massacre. That was only 170-odd men. We are going to end up with 1500 men here, if things don’t go right, at least 1500.”

Heather Ann Thompson, explain why you begin with that.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, it’s really important for folks to realize that this rebellion of nearly 1,300 men for basic human rights ends brutally when the state of New York retakes the prison. And even the hostages were, at the end of this rebellion, begging the governor not to come in with force and to do the right thing—improve conditions in the prison. And that quote and several others in the very beginning of the book really reflect the desire of all participants to come to a peaceful resolution and finally do something about the terrible conditions in Attica.

AMY GOODMAN: For so many years, that 39 number, 39 men dead, the state authorities said that the prisoners slit the throats of their hostages. That turned out not to be true in even one case. Were they all killed by the state troopers?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Yes. On the day of the retaking, every death was at the hands of trooper or correction officer bullets. And the state stood out and told the entire world that the prisoners had in fact killed the hostages. And that story had a devastating effect on the long-term—on the future of criminal justice policy in this country. It really fuels the engine of punitive policy. And to this day, citizens will tell you that the prisoners killed the hostages at Attica.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, one of the interesting things, this was at a period in American history when racial conflict was perhaps at its strongest, but yet Attica represented an interracial rebellion.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: That’s right.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: There were white inmates and Latino inmates and African-American inmates who banded together. You tell the story of Sam Melville, the Weather Underground member who was in Attica at the time and participated in the rebellion. There were many Latinos. And, in fact, when we were in the Young Lords, we actually had a Young Lords group in Attica prison.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: That’s right.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And we had two of our members, Jose “Fi” Ortiz, who was a leader of the Young Lords, and then Jose Paris, “G.I.,” who had come out of Attica, who went up there as part of the negotiating committee. So this was really an example of racial solidarity among an oppressed group.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Indeed. And that’s why it was so threatening to the state. Somehow, you have 1,300 men, who are otherwise divided by language or political persuasion or ethnicity or race, and they come together over the basic fundamental desire to be treated as human.

AMY GOODMAN: David Rothenberg, you were called in by the prisoners, one of the 35 people, along with William Kunstler and others, the late great lawyer. Talk about what your involvement was, why the prisoners wanted you there and what you found there.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Well, I had been—Fortune Society had just started, and we were a volunteer organization at the time. But we were in—I was in correspondence with Roger Champen and Herbert Blyden, two of the men who emerged as leaders. And we had a little, simple newsletter, which was banned. And we went to court and won. The federal courts ruled, Fortune v. McGinnis, who was the commissioner, that they had no right to censor the inmate reading material. So I think they thought that we were this powerful organization that could make changes. And when they took over and they asked—they didn’t trust the state in the negotiation; in the demand, they asked for a list of people to come in and act as observers, and my name was on the list. So I got a call from Arthur Eve, who was an assemblyman from Buffalo, saying, “Will you come up to Attica?” And I said, “Not alone.” And two other guys from Fortune, Kenny Jackson and Mel Rivers, we flew up into the yard.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, David, the importance of having that group there? Because in most prison uprisings, there are no outside witnesses, but here you had this group of people, and not just Kunstler and you, but there were elected officials, Tom Wicker—

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Herman Badillo.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Tom Wicker of The New York Times. There was a large group of people that went up there and actually then had a different version of events than the official version.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: This was a politically sophisticated group of inmates, which is why the state thought that outside revolutionaries were sponsoring—were igniting the trouble. What in fact caused the trouble is you can’t put 2,000 people in cages, treat them brutally and not think there’s going to be repercussions. That’s what happened at Attica.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you describe some of these pictures you brought in? And especially, as you know, because you’re on WBAI in New York, speak for a radio audience, describe in detail.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Well, these—this is the—that’s Commissioner Russell Oswald meeting with some of the leaders. I recognize L.D. Barkley and Roger Champen and Herbert Blyden. That’s people that I know. I think that’s Flip Crowley there. And—

AMY GOODMAN: And another picture is prisoners naked in the yard.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Oh, this was horrible. They stripped everybody. And then they put them—when they brought them inside, they smacked them with—in their ankles and their knees and their testicles, so that it was brutal. It was—you know, they could have taken over the institution by gassing it, which they did. They didn’t have to fire a bullet.

AMY GOODMAN: Frank “Big Black” Smith, when he was laid out—

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —describe. They made him hold a football with his chin—

DAVID ROTHENBERG: For hours.

AMY GOODMAN: —laid out naked on a table, as they beat him. Why the football?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: It was there.

AMY GOODMAN: Heather Ann?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, it was there. And he was—he was one of the players on a football team. And he had been targeted because the state accused him of having castrated a guard. So they tortured him to say that if he dropped that football, they were going to shoot him. And he had every reason to believe it, since he had just witnessed, over the course of 15 minutes, another massacre.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Heather Ann Thompson, the—not only was the scandal of the actual massacre that occurred there that—at the rebellion itself, but then the cover-up afterward. If you would talk about your quest to find out what actually happened?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, so, for 45 years, the majority of the records for Attica remain sealed by the State Attorney General’s Office, or at least very difficult to get. And the reason is that for all of the death at Attica, no member of law enforcement was ever held responsible. So, the book was the journey to figure out who had created so much trauma; what had happened in the Governor’s Office to lead to this retaking; who were the members of law enforcement that not only shot their weapons, but indeed the highest levels of the state police, who worked very had to tamper with evidence, to conceal evidence and to protect their own. And that was a key journey for finding out that information.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And you traced the chain all the way up to Washington, D.C., and the White House, right? In terms of—

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Indeed. The story of Attica resonates nationally and internationally, both because it was televised and people cared very much what happened there, but also because at every level, for the next 45 years, from the lowest-level workman’s comp bureaucrat to the presidency of the United States, the Supreme Court, the Justice Department, everyone turned a blind eye to the torture that continued to go on behind the walls of Attica in the wake of the rebellion. And so that story is very important.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: There are heroes in her book, and one of them is Malcolm Bell—

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Indeed.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: —who was a conservative Republican who was hired by the state to be an investigator. And he couldn’t remain quiet, because he saw the cover-up.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: That’s right.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: And he emerges from your book as a really heroic figure.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Yes.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: It changed his life, because he discovered the truth.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: There are a few heroes, and they really stand out—the coroner, who went public, at great expense to himself, to tell the world that, no, in fact, the prisoners hadn’t killed the hostages, that it was trooper bullets. Malcolm Bell is a hero because he blew the whistle on the inside of the Attica investigation, that in fact they were not going to go after the police, no matter that all the deaths were at the police’ hands.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what about that call you received from a clerk in Buffalo about this trove of documents?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, indeed. I had been looking and looking for Attica documents, combing upstate New York, and happened upon a whole series of documents that happened to just be in a random room in a courthouse. And, frankly, I don’t think that they knew what was there. It was a wall full of Attica documents. And the most important in those were evidence from the state’s own investigation, its own records about who had done what at Attica.

AMY GOODMAN: And we’re going to talk about who did what after this break. We’re speaking with Heather Ann Thompson, who wrote the book Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. David Rothenberg with us, who is a fixture in New York, is a writer and a WBAI producer, the Pacifica Radio station here in New York. At the time, though, in 1971, he was a member of the Attica observers’ committee, one of 35 people brought into Attica to negotiate on behalf of the prisoners. He’s founder of The Fortune Society. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Attica Blues” by Archie Shepp, here on Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. It’s the 45th anniversary of the Attica uprising, one of the largest prison uprisings in U.S. history, began September 9th, 1971, over prison conditions. On September 13th, five days later—four days later, the New York governor, Nelson Rockefeller, called out the state troopers. They opened fire, killing 39 men, prisoners and guards, critically wounding scores of others and injuring hundreds more.

Our guest is the woman who’s written the definitive book on this. It’s just out, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Heather Ann Thompson, a professor, American historian at University of Michigan. And David Rothenberg, who, back in '71, was a member of the Attica observers' committee, one of 35 people brought into Attica to negotiate on behalf of the prisoners. He would go on to found—no, he went—he was—founded already, right?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: The Fortune Society, for people coming out of prison, to help them transition. The Muslim prisoners, David?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: They—well, and in your book, you validate what we witnessed. It was the Muslim brothers that protected the guards that were the hostages. They surrounded them to make—they knew that they had to be protected and saved.

AMY GOODMAN: Heather Ann?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Indeed. I mean, the yard was peaceful, the yard was organized, in no small measure to the Muslim brothers in the yard, the Attica brothers, who were insistent that the hostages were important and that the men sitting there in that circle would have mattresses to sleep on and food to eat. And that was crucial, because, at the end, that’s why the guards are asking Rockefeller to try to help these guys and do the right thing, rather than gun them down, which, of course, is what happens.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yet, you also write in your book that Minister Farrakhan, who the prisoners had requested to be one of the negotiators, declined to do so, because, supposedly, the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, had told him not to.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, that was certainly evidence that I found. But it was interesting, because a lot of people were asked to come, and, for a variety of reasons, they couldn’t be there. And yet, there are so many observers, such as David, and those folks played a remarkable role. I mean, they kept insisting again and again that they stick to the negotiations, that the state negotiated in good faith, and, indeed, at the very end, were calling Rockefeller, insisting that he at least come to Attica, at least assure these guys that if they surrendered, that they would not be harmed. And he refused to do it. And in—

AMY GOODMAN: Why?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, for multiple reasons, but not the least of which was his own political ambitions. His party had moved very much rightward. He wanted to impress the Republican Party that he was tough on crime. But also it was a black rebellion, and—

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Describe what you write in the book about the breakfast. I’m reading the book, and I just threw it down when she was describing the planning strategy by the state.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Yeah, well, they were very clearly intent on going in with force from the very beginning. The only reason, incidentally, they didn’t go in earlier was because of the observer team there. And when they finally do go in, I discovered that they deliberately don’t tell the prisoners that it’s going to be a bloodbath if they don’t give up. They don’t give them an ultimatum. And while it’s happening, Rockefeller is eating a scrambled egg breakfast with bacon in his mansion and is being congratulated by Richard Nixon for having handled this so beautifully.

AMY GOODMAN: What was Richard—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what about Oswald, the warden, his role?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Yeah, the commissioner.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, Oswald was a very tragic figure.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Yes.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: He was a liberal, a prison reformer. It was, really, at his insistence that negotiations continued as long as they did with his own people in the Department of Corrections. But at the end of the day, he proves very ineffective in halting what has been decided above his pay grade, which is there’s going to be a retaking.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: I always said he was a good man who failed history.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Yeah, I think that’s right.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: He didn’t rise, because he had been parole—he became commissioner of correction because of his progressive position—

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Right.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: —as parole head. And he was considered a leader. And the fact that he went up there was unprecedented. He went—one of the pictures is him sitting with the—he went in the yard. But he was—he didn’t understand them.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Exactly, exactly.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: He was—he was a—I don’t know how you describe a progressive academic—no, I don’t want to blame the academics.

AMY GOODMAN: Why—I want to ask about the negotiating team, you and the negotiating team. If you had stayed in the yard, would the state troopers have opened fire? What word did you get? Were you told to leave?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Well, we were in and out. And eventually it was reduced down to five people—Clarence Jones, Kunstler, John Dunne, Herman Badillo—because we felt we were too cumbersome of a group. But there were points in the—we would meet after the takeover for months and months at Kunstler’s house. And the feeling was, we would have been killed had we stayed there.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: One of the most important things in the book that I discovered was there was a myth for years after Attica that the hostages that were killed was—was a mistake, accidental, shouldn’t have happened. And it’s very clear that the state knew the hostages were going to die. They discussed it before they went in. And their own state employees were dispensable. I think it’s pretty clear that had the observers been in there, that there was no controlling this once it was unleashed. These prisoners were at the mercy of people who had been, for four days, passing out weapons indiscriminately. And when they went in, these troopers took off their identifying badges so that they would not be held accountable for what then happened.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: They used some—some of them used their personal guns, as well?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Absolutely.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And you also seem to—talk about this question of when some of the prisoners were killed. Was it all in the initial shooting, or were some deliberately killed by the guards afterwards?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, I think the evidence is pretty clear that, as David has said elsewhere, law enforcement had control of this prison from the moment they dropped the gas. The gas is a powder. It clung to people’s nasal passages, made them sick, incapacitated everyone in the yard. Then the shooting begins. For 15 minutes, it continues. And what is significant is that all of the observers reported later that they could still hear gunfire many hours later that day. And many of the prisoners reported that not only had people been killed after the retaking, but the very specific men had been targeted by law enforcement.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Barkley and Melville, people have told me that they had seen them alive after the takeover. L.D. Barkley, who was so eloquent and whose voice was heard on national television during the protest, was targeted, as was Sam Melville, who was perceived as a traitor to his race because he was white.

AMY GOODMAN: The second epigraph in the book is a quote from the national guardsman James O’Day, who describes an incident at Attica. This is the national guardsman: quote, “The officer pulled out a Phillips screwdriver and told the naked inmate to get on his feet or he’d stab the screwdriver into his rectum. … Then he just started stabbing him.”

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: That’s right. In the aftermath is when the real brutality begins. The doctors are trying to help prisoners, while guards are dumping them off of stretchers, kicking them, urinating into wounds, making the most horrific scene unfold. And, indeed, this national guardsman, among many, was trying to tell people outside what was happening. This particular man tried to get the Justice Department to look into this. He called the FBI. He called the Justice Department. And again, at every level, people abandoned these guys to this fate.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Why the book is so powerful is, a lot of these stories I heard over the years, one by one, from individuals, as they came out. To see it collected at one time gives you that overwhelming sense of what the state did—and didn’t have to do.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And you also say that there were some of the records you found, investigators concluded that particular guards killed particular prisoners, but never pursued any attempts to charge them with those.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: That’s right. And, of course, there are many more records we have yet to see. But the records I did see indicated that despite the attempts of the state police to tamper with evidence and conceal evidence, there was evidence. And that evidence not only indicated specific troopers that had killed specific inmates, but also specific troopers who had killed specific hostages. And those people could have been indicted, and instead the state chose to indict 62 prisoners for all that had gone wrong at Attica, again sending the message to the world that Attica was about prisoner barbarism and that those sorts of people don’t deserve basic human rights.

AMY GOODMAN: And the names you name have never been named publicly before.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: That’s right. And indeed—

AMY GOODMAN: What surprised you most? Who did you talk about?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: What surprised me most was actually not the lower-level troopers who I name, but actually the highest-level troopers, the head of the New York State Police, who—people who would literally step in to make a low-level trooper resign rather than face prosecution, top police officers who are tampering with photographs. But again, the responsibility still lies with the state of New York. They are the ones that sent these guys in and then, afterwards, allowed these guys to investigate the retaking that they had just carried out.

AMY GOODMAN: And the settlement?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: The settlement against the state?

AMY GOODMAN: With the prisoners.

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, the settlement was very important. It took 30 years. It took determination on the part of these men, such as Frank “Big Black” Smith, to stick with it. But I think the nation was also feeling like they finally got justice. No brother feels like they got justice. It was a pittance for some people. It was $6,500 for a death, at the end of the day. And the cost was still there, because the state still has not admitted responsibility, still denies that anything happened at Attica.

AMY GOODMAN: A comment on the prison strike today?

HEATHER ANN THOMPSON: Well, I think we are back here. And we are back here in no small part because the nation failed to learn the lessons of Attica, and we created one of the most brutal prison societies in the world. And as was the case in Attica, when you treat people as animals, and they are human beings, they will resist. And we are seeing that across the country again today.

AMY GOODMAN: Heather Ann Thompson, we want to thank you for being with us, author of Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. And, David Rothenberg, member of the Attica observers’ committee, thanks for joining us, and founder of The Fortune Society.

That does it for the show. Tonight, Nermeen Shaikh and I will be speaking at 6:30 at the Toronto International Film Festival at the premiere of All Governments Lie, documentary world premiere. On Saturday, we’ll be at 1:30. Check democracynow.org for details.

Media Options