Topics

Guests

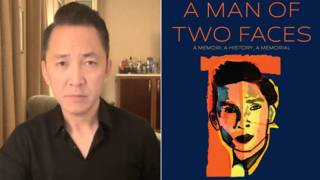

- Ai Weiweiworld-renowned Chinese artist and activist. In 2009, Ai Weiwei was arrested and beaten by Chinese police. In 2011, the Chinese government arrested and imprisoned him without charge for 81 days. Ai Weiwei has received numerous awards, including the 2015 Ambassador of Conscience Award from Amnesty International and the 2012 Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent from the Human Rights Foundation. He is now the Einstein visiting professor at the Berlin University of the Arts. He is the director and producer of the new documentary, Human Flow.

The United Nations says there are now more refugees worldwide than at any time since World War II. The journey and struggle of these 65 million refugees is the subject of Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei’s epic new documentary. It’s called “Human Flow.” For the documentary, Ai Weiwei traveled to 23 countries and dozens of refugee camps. We speak to world-renowned Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: In a Democracy Now! special today, we spend the hour with the world-renowned Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei. ArtReview magazine has called him the most powerful artist in the world. He’s also been called the most dangerous man in China.

Ai Weiwei was born in 1957 in Beijing. His mother was writer Gao Ying. His father was the revered poet Ai Qing. The year after Ai Weiwei was born, his father was named an enemy of the people. He and his family, including 1-year-old Ai Weiwei, were sent to hard labor camp in the Gobi Desert in remote northwest China. Ai Weiwei spent the next 16 years of his life growing up in hard labor camps, with harsh living conditions and little formal education. The family had only one book: a large French encyclopedia.

At 19, Ai Weiwei and his family returned to Beijing, and he enrolled in the Beijing Film Academy to study animation. There, he became part of a group of avant-garde artists organizing against government control of the arts—their slogan, “We demand political democracy and artistic freedom.” He was also a part of a small political movement of students who produced posters calling for reforms, and pasted them on them on a brick wall that came to be known as the Democracy Wall.

When the leader of that movement was sentenced to 15 years in prison, Ai Weiwei decided to move to New York City. It was 1981. Ai Weiwei spoke no English, had $30 in his pocket. He settled in the Lower East Side and befriended Allen Ginsberg and other influential artists. He briefly studied at the Parsons School of Design, but dropped out after his professor told him his drawings had no heart. Instead, he held a string of odd jobs, working in construction, cutting grass, cleaning houses, babysitting, even winning money in Atlantic City as a blackjack guru.

In 1993, Ai Weiwei returned to China because his father was ill. He founded a highly influential architecture firm, named FAKE Design, and dedicated himself to art and writing. In 2008, after a massive earthquake in Sichuan, China, Ai Weiwei launched a citizen investigation to collect the names of the more than 5,000 schoolchildren who died, partially as a result of the highly shoddy government construction of the schools. Ai Weiwei was highly critical of the government’s response to the earthquake, saying, quote, “They intimidate, they jail, they persecute parents who demand the truth, and they brazenly stomp on the constitution and the basic rights of man,” unquote.

While his citizen investigation catapulted him to international fame, it also enraged Chinese government officials. In 2009, his popular blog was shut down. A few months later, police broke into his hotel room and attacked him, punching him in the face and causing cerebral hemorrhaging. He had to have emergency brain surgery, which he documented in his film So Sorry.

Then he launched his most famous installation to date: a massive mosaic of 9,000 children’s backpacks mounted on the exterior wall of the German art museum Munich Haus der Kunst. The backpacks spelled out in Chinese characters the words of one mother whose child was killed in the earthquake: quote, “She lived happily on this earth for seven years,” unquote.

In 2010, Ai Weiwei was placed under house arrest, after the Chinese government demolished his studio. Then, in 2011, he was arrested at the Beijing airport and held for 81 days without any charges. Chinese authorities seized his passport, refused to return it until 2015. Once that passport was returned, he moved to Berlin, Germany. He’s also faced constant surveillance, a topic which he explored earlier this year in his exhibition Hansel & Gretel, set in New York’s Park Avenue Armory, in which visitors are relentlessly tracked by cameras.

Among his other famous installations was his 2010 show Sunflower Seeds at the Tate Museum in London, in which Ai Weiwei filled a hall of the museum with more than 100 million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds. He currently has a solo exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., called Trace. The exhibit features 176 portraits of activists and free speech advocates made of Lego bricks. He also has a major new exhibition opening next week here in New York City in which he’s erecting security fences and cages across the boroughs, including under Washington Square Arch and in Central Park near Trump Tower, to explore the rise of nationalism and the closure of borders worldwide. It’s called Good Fences Make Good Neighbors.

AI WEIWEI: The fence can be between neighbors to divide, to set up some kind of border. It’s about territory, about dividing to push the others away or to stop others from crossing. Generally, it reflects a misunderstanding of humanity.

AMY GOODMAN: Ai Weiwei is also the director of a major new documentary on the struggle, the journey of refugees worldwide, called Human Flow. For the documentary, he traveled to 23 countries, visiting dozens of refugee camps. This is the trailer, which takes us to Iraq, Jordan, Gaza, northern Greece and Kenya.

UNIDENTIFIED 1: Being a refugee is much more than a political status. It is the most pervasive kind of cruelty that can be exercised against a human being. You are forcibly robbing this human being of all aspects that would make human life not just tolerable but meaningful in many ways.

UNIDENTIFIED 2: The more immune you are to people’s suffering, that’s very, very dangerous. It’s critical for us to maintain this humanity.

CAPTION: Over 65 million people in the world today have been forcibly displaced from their homes.

REFUGEE 1: [translated] I’ve been roaming endlessly with my son for 60 days now. Nobody has shown us the way. Where am I supposed to start my new life?

UNIDENTIFIED 3: If children grow up without any hope, without any prospects for the future, without any sense of them being able to make something out of their lives, then they will become very vulnerable to all sorts of exploitation, including radicalization.

INTERVIEWER: [translated] Why are you here?

PALESTINIAN GIRL 1: [translated] We went for a stroll.

PALESTINIAN GIRL 2: [translated] For fun. It’s the only place to escape in the big prison of Gaza.

UNIDENTIFIED 4: The officials came here and told them, “Look, there’s no way you’re going to get papers to continue. Either you go voluntarily, or we arrest you.”

CAPTION: Witness the global journey of millions of men, women and children filmed across 23 countries.

AI WEIWEI: I respect you.

REFUGEE 2: We have to respect you.

AI WEIWEI: I respect your passport, and I respect you.

UNIDENTIFIED 5: It’s going to be a big challenge to recognize that the world is shrinking, and people from different religions, different cultures are going to have to learn to live with each other.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s the trailer for the new documentary Human Flow. It’s directed by Ai Weiwei, the internationally renowned Chinese artist. He’ll be back with us live after break.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Just Climb the Wall,” sung and written by Ai Weiwei. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. The United Nations says there are now more refugees worldwide than at any time since World War II. The journey and struggle of these 65 million refugees is the subject of Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei’s epic new documentary called Human Flow. For the documentary, Ai Weiwei traveled to 23 countries, dozens of refugee camps.

He joins us now in our New York studio, yes, the world-renowned Chinese artist, dissident, activist Ai Weiwei. He has received so many awards, including the 2015 Ambassador of Conscience Award from Amnesty International, the 2012 Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent from the Human Rights Foundation. He’s now the Einstein visiting professor at the Berlin University of the Arts, also director and producer of this new documentary that’s opening around the country, Human Flow.

Ai Weiwei, it’s an honor to have you here.

AI WEIWEI: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about why you decided to make this epic film that took you across the world. You, a man, who have, yourself, been internally displaced in China, had to leave China. Talk about your life and how it intertwines with this story in the film.

AI WEIWEI: Well, 2015, I had got my passport back, so I can start to travel. I went to Germany. And in Germany, you’re facing the reality about 1.2 million refugees come to the land. So it makes me wonder: Who are they? And I decided to go to Greece. And the last was to really look at those people and how they get on the land. So, in there, I met the first boat—

AMY GOODMAN: You went to Lesbos, in Greece?

AI WEIWEI: Yeah, Lesbos, in Greece. So, on the shore, I met the first boat approaching the shore. And, you know, I see those people—women, children and old people. Some are crying—you know, it’s just an unthinkable situation—climbing down this little boat. And then another boat, another boat. You know, sometimes you have 30, 40 boats a day. And so, it made me really wonder and have a curiosity about what is really going on in the world today.

So I decided to move my studio to Lesbos. And, you know, we have 20, 30 people there, start filming. And eventually, we have to go to the other side, Turkey, and to go to the Middle East, and then go to Asia and Africa, to make this film. It’s a very big film. It takes us about one year to finish. We visited about 23 nations, 40 camps, and interviewed about 600 people, and has 900 hours of footage.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you went to the Middle East, as well. Where did you go?

AI WEIWEI: We went to, first, Jordan, Lebanon and Israel, Gaza. Then our team also go to Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan. You know, all those places.

AMY GOODMAN: What did you find in Gaza?

AI WEIWEI: Gaza is a situation not people being pushed away from home, but being put in like a big jail. You know, millions of people stays in—basically in this—their border, and they cannot leave. So, the situation is extremely difficult. They only have very little resources, and many people survive only from the help from the United Nations. And the water, polluted. Electricity, only given a few hours a day. So, it’s an extremely difficult situation.

AMY GOODMAN: And where did you go in Israel?

AI WEIWEI: Israel, I’ve been Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and West Bank, you know, Palestine area.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to a clip from Human Flow, your new documentary. This is Dr. Cem Terzi from the Association of Bridging Peoples. He works with Syrian refugees in Turkey.

DR. CEM TERZI: There is nothing in this agreement in favor of refugees. Turkish law system only allowed them under the temporary protection. It means they have no international rights here. One day, the government decides, “I will send them back.” The government can do this, because they are not defined as a refugee. No international rights for them. They need a social integration program, job permits. They need jobs. They need a standard income and to buy food or to pay their rent. The children need to go to school. Majority of them, last five years, didn’t go to school even one day.

AMY GOODMAN: So that’s Dr. Cem Terzi from the Association of Bridging Peoples, who works with Syrian refugees.

AI WEIWEI: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us more about him and what you found there.

AI WEIWEI: The doctors were in tears. And they have been a major force to helping the refugees in Turkey. And recently, he has been fired, and with 12 other professors, because a year ago they signed some peace treaty. So, many, many—even those doctors whose—his own life is threatened in Turkey. And their team really did a lot of work for helping refugees and, you know, to take medical care for them.

Media Options