Guests

- Maya Wileysenior vice president for social justice and professor of public and urban policy at The New School.

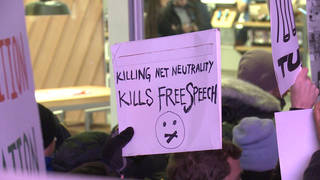

Last week, the Federal Communications Commission, known as the FCC, voted to dismantle landmark “net neutrality” rules established in 2015 after widespread organizing and protests by free internet advocates. These rules required internet service providers to treat web content equally and not block or prioritize some content over others in return for payment. The repeal of these rules was widely opposed by the American public, with more than 20 million people submitting comments to the FCC. Thursday’s vote also means the government will no longer regulate high-speed internet as if it were a public utility, like phone service. We speak with Maya Wiley, senior vice president for social justice and professor of public and urban policy at The New School.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We end today’s show looking at the next steps in the fight to keep the internet free and open. The Federal Communications Commission, known as the FCC, voted last week to dismantle landmark net neutrality rules established in 2015 after widespread organizing and protests by free internet advocates. These rules required internet service providers to treat web content equally, not block or prioritize some content over others in return for payment. The repeal of these rules was widely opposed by the American public, with more than 20 million people submitting comments to the FCC. But Trump’s chairman of the FCC, Ajit Pai, had lobbied heavily to repeal the rules. On Thursday, Ajit Pai, a former Verizon attorney, was joined by two fellow Republican commissioners, and the FCC voted 3 to 2 for a repeal. The FCC’s vote to repeal net neutrality is the latest and most controversial of a series of changes led by Chairman Ajit Pai. Over the last year, he has also loosened rules aimed at limiting media consolidation, and scaled back a program aimed at expanding broadband access among low-income Americans.

For more, we’re joined by Maya Wiley. She’s senior vice president for social justice and professor of public and urban policy at The New School.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Professor Wiley.

MAYA WILEY: Thank you, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about your concerns. This vote that happened on Thursday, is it set in stone? There are still movements all over the country that are pushing back very hard?

MAYA WILEY: Absolutely. Well, let’s just start with the fact that this is a devastating blow to all the ways that we’ve come to understand the internet. Even those who are part of the founding of the internet have expressed deep, deep concern for the failure to protect net neutrality. And even though we just got the rules in 2015, the truth is, we’ve been fighting for net neutrality since the mid-2000s. So, this isn’t really new. And the fact that there was a fight meant that we were essentially seeing some controls on—in the gentle sense, on internet service providers to do the right thing.

So, what’s happened now is, first of all, you have members of Congress considering whether to use the same act that Donald Trump used to roll back privacy protections regulations that the Obama administration had approved, which allows 60 days for Congress to essentially say, “Repeal those rules.” Now, given the current makeup of the House, obviously, unless more Republicans start to realize that their own constituents will be harmed by these new rules, then we may not see that pass.

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain how you see—what you think is most going to be lost in this rollback.

MAYA WILEY: You know, I think what people have to understand is the internet service providers, of which we have far too few in this country, right? Competition, we should have much more than we have. We don’t, because we’ve essentially granted them monopolies in exchange for providing what’s called universal service. What the FCC has done is actually said, “You know, we’re not even going to put you in the category anymore of being required to provide universal service. We’re really going to treat you as an information provider,” which, of course, really isn’t an accurate way of thinking about internet service provision anymore.

But what that really means is, we’ve got 62 million Americans in urban areas and 16 million Americans in rural areas that still don’t have broadband at home, and essentially saying, “OK, and we’re not actually going to say universal service to you anymore,” is one of the big aspects of this new rule that we have to understand. So, and in addition, when you add the content blocking or throttling content, when we have very little competition in the space, it’s not like consumers are going to have a choice of, say, going to another provider, in very many places, to say, “Well, I want to be sure that you’re not going to block my content.”

AMY GOODMAN: Do you see whole cities getting short shrift here?

MAYA WILEY: Well, I think all over the country we’re going to see—

AMY GOODMAN: Especially poor areas.

MAYA WILEY: Especially poor—poor areas are already in trouble, right? I mean, we should understand that there’s still fundamentally a digital divide in this country, both in urban and rural areas. And as I said, in urban areas, it’s 62 million people. A big part of that, for urban areas, is cost. So, for communities of color, what we’re talking about is seeing costs go up, right? I mean, because you’re essentially saying to providers, you can actually charge—you’re going to charge companies, but folks are going to speed up their content potentially. But that means that they’re going to pass those costs off to consumers, which is going to make it even more costly. And we, in the United States, pay more for less. You know, we pay a lot more for our internet and get a lot poorer service.

AMY GOODMAN: Then you have, right here, Eric Schneiderman, the New York attorney general, threatening to sue to block the repeal, and a dozen states’ attorneys generals investigating, quote, “fake comments”?

MAYA WILEY: Yes. So—

AMY GOODMAN: Explain.

MAYA WILEY: We have at least—what have been uncovered is about 2 million comments by bots, which are not people, ergo the name “bot,” that, essentially, though, the allegation is that they pose—these bots pose as actual people and submit a comment. That’s identity theft. And so, what Eric Schneiderman was doing was saying, “I’m investigating the New York state crime of identity theft, because we’ve had residents whose identities were falsely used to make comments that they weren’t making.” He had asked the FCC to hold back on passing the rule until he had finished his investigation. They refused. They also refused to have public hearings and allow a public discussion of the new rules. So, what you’re—that’s why you’re seeing so many attorneys general working to protect their residents, whose identities have been stolen, and trying to understand—

AMY GOODMAN: Minority businesses?

MAYA WILEY: Minority businesses, it’s a big issue, because, as we know, one out of three women-owned businesses is owned by black women. And immigrant businesses are amongst the fastest-growing, along with black women businesses. If you have to pay to get your content, your services, your products to customers faster, and therefore compete, and you’re a small business, that means you’re in trouble. And that’s going to kill some of the innovation we’re seeing in communities of color.

AMY GOODMAN: But you say it’s not a done deal?

MAYA WILEY: It’s not a done deal. This fight is far from over. We’re also going to see lawsuits from the Free Press. We’re going to see lawsuits from the ACLU. So, in addition to Congress—of course, we should be fighting Congress to pass legislation to re-establish it, but there’s a lot of fighting to come.

AMY GOODMAN: Maya Wiley, senior vice president for social justice, professor of public and urban policy at The New School.

Media Options