Guests

- Allan Nairnaward-winning investigative journalist.

- Sarah KinosianHonduras-based reporter.

- Jan SchakowskyDemocratic congressmember representing the 9th District of Illinois.

National police in the Honduran capital Tegucigalpa—including elite U.S.-trained units—refused to impose a nighttime curfew Monday night that was ordered by incumbent President Juan Orlando Hernández after days of protests over allegations of fraud in the country’s disputed election. The move comes after at least three people were killed as Honduran security forces opened fire on the protests Friday night in Tegucigalpa. Protests erupted last week after the government-controlled electoral commission stopped tallying votes from the November 26 election, after the count showed opposition candidate Salvador Nasralla ahead by more than 5 percentage points. The commission now says Hernández has pulled ahead of Nasralla, by 42.98 percent to 41.39 percent, after a recount of suspicious votes. This comes as Nasralla and international observers are calling on the Honduras electoral commission—which is controlled by President Hernández—to carry out a recount. We speak with Allan Nairn, award-winning investigative journalist; Sarah Kinosian, a Honduras-based reporter; and Congressmember Jan Schakowsky, who represents the 9th District of Illinois. Her op-ed published in The New York Times is headlined “The Honduran Candidate.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We turn now to the political crisis in Honduras. On Monday night, national police in the capital Tegucigalpa, including elite U.S.-trained units, refused to impose a nighttime curfew ordered by the government after days of protests over allegations of fraud in the country’s disputed election for president. This is one of the COBRAS anti-riot squad speaking in a video posted on Facebook.

COBRAS ANTI-RIOT SQUAD MEMBER: [translated] This is a message for the violence to end. There is no need for people to be in the streets killing each other for something the politicians can resolve among themselves. It is not our job. We are not acting according to any political ideology. This is our feeling. Most of my colleagues are tired of being in the streets. Our families have been locked at home for more than 15 days. And the problem continues every day. The crisis continues. Our call is that all this ends, because we are not willing to come to the streets and confront the people or engage or repress the people, crack down on the people.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The move by police comes after at least three people were killed as Honduran security forces opened fire on demonstrators Friday night in Tegucigalpa. Protests erupted last week, when the government-controlled electoral commission stopped tallying votes from the November 26th election and after the count showed opposition candidate Salvador Nasralla ahead by more than 5 percentage points. The commission now says President Hernández has pulled ahead of Nasralla by 42.98 percent to 41.39 percent, with 99.96 percent of the votes tallied. Electoral officials say they will not declare a winner in the election yet, in order to allow the filing of challenges and appeals. This comes as international observers are calling on the Honduras electoral commission, which is controlled by President Hernández, to carry out a recount. The Organization of American States and the European Union have supported Nasralla’s demand for a recount. This is Marisa Matias, head of the European Union mission.

MARISA MATIAS: [translated] The count has not yet finished. The process is far from over. That is to say, there’s still some time for the presidential candidates and for the parties to put forward their appeals, their challenges. This should be done by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal.

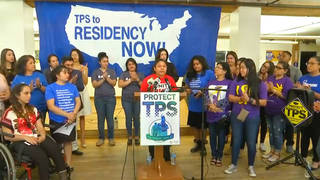

AMY GOODMAN: This comes as the U.S. Embassy said in a statement it’s, quote, “pleased Honduran election authorities completed the special scrutiny process in a way that maximizes citizen participation and transparency,” unquote. Meanwhile, here in New York, people rallied in Union Square Monday in solidarity with those supporting Nasralla.

CARLA GARCIA: [translated] My name is Carla Garcia. I live in New York. And I’m standing here today together with my Honduran community. It doesn’t matter if you are indigenous, Garifuna or a person who lives in the city. We are all facing a fraudulent election where one person is trying to continue ruling with his party, trying to continue governing indefinitely. And the people are saying, “No more. We want liberty.” That’s why I’m here accompanying the Honduran people.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined by three guess. In Honduras, we’re joined by two award-winning journalists, Allan Nairn as well as Sarah Kinosian. Her latest piece for The Guardian is headlined “Honduras: police refuse to obey government as post-election chaos deepens.” And on Capitol Hill, we’re joined by Congressmember Jan Schakowsky, who is—represents the 9th District of Illinois. Her op-ed in The New York Times is headlined “The Honduran Candidate.”

We welcome you all to Democracy Now! Let’s go first to Allan Nairn, who is in the streets of Tegucigalpa, as Sarah was last night. Explain what you’ve watched.

ALLAN NAIRN: Well, Honduras has been in the midst of an uprising of the poor, joined by many in the middle class. It’s essentially a democratic electoral uprising against the government and the oligarchy, who are trying to impose Hernández, who is a protégé of White House Chief of Staff General Kelly, for another term.

And then something extraordinary happened last night, where the poor were joined in this revolt by a big chunk of the security forces, the police at the COBRA headquarters. COBRA is an elite unit that is charged with working on things like counterterrorism, narcotics. For hours upon end, police from all over, from many different units, came streaming into the headquarters to support their rebellion, their uprising—a refusal to carry out any more repression. At one point, according to the police there who I spoke to, it appeared that about one-fifth of the entire national police force had gathered inside the COBRA headquarters. And reports from all over the country show that this is happening everywhere, everywhere else.

This was triggered, in important part, by a decision by the U.S. State Department taken on Tuesday, the 28th, to certify that Honduras was honoring human rights and fighting corruption. With that certification, that greenlighted new U.S. aid to Honduras, essentially, in effect, gave a green light to complete the fraud, and also gave a green light for state escalation of what has really become a class war. And on Thursday, the 30th, an election technician working inside the Supreme Electoral Tribunal sent a private chat message to a friend of his. And that message, which I saw, read, ”El fraude ya se hizo.” “The fraud has now been done.”

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, I’d like to bring in Representative Jan Schakowsky. You’ve been very vocal, especially in the op-ed piece you had in The New York Times, about the whole issue of whether President Juan Orlando Hernández is even—should even be legally running for re-election, and the questions you’ve raised, as well, about this vote. Could you talk about that?

REP. JAN SCHAKOWSKY: Well, this is really an illegal election, according to the laws in Honduras. In fact, it was the cause of the coup, supposedly, in 2009, when President Zelaya just wanted a referendum to see if people wanted to have—make a change and allow for the re-election of the president. What Hernández did was to stack the Supreme Court and change the rules so that he could run again. And now what we’re seeing is that in order to win the popular election, then it looks like extensive fraud has occurred.

And it’s just remarkable to me that the United States of America has continued—two days after this election, which was under a cloud to begin with, would recertify that taxpayer dollars should go to the military, to the training of the armed forces and the police in Honduras, that they’re a great ally of the United States, that they have not violated human rights and democracy in Honduras. So, this is a situation where many of us in the Congress are saying we want to see a full recount, and we want to see the passage of our Berta Cáceres Human Rights in Honduras Act, that says, “No, no money is going to go, unless we make sure that human rights are acknowledged and not abused in Honduras.”

AMY GOODMAN: Sarah Kinosian, you, too, have been on the streets of Tegucigalpa. What are the people demanding on the streets right now? And the significance of what Allan just described? You, too, writing about the police going back to the barracks, saying they will not repress the people. Are they calling for a new election?

SARAH KINOSIAN: Yeah. So, I’ve gotten various answers to that. Some people are calling for a new election. But a lot of other people I talk to said, you know, “What’s the point of having a new election? They’ll just commit fraud again, because the electoral body, the TSE, is controlled by the ruling party, by Hernández’s party.”

I’ve got a larger amount of people that are calling for the recount of the 5,000 votes that apparently were counted after a computer glitch and which essentially changed the trend of Nasralla winning. That’s probably the biggest account of fraud that people are upset about. You know, the army—excuse me, the police last night called for a recount of the votes from all polling stations, so 18,000. So, you know, we’ll have to see what happens. But right now it seems that a recount of the 5,000 votes is the main issue on the table.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And the votes that you’re talking—

SARAH KINOSIAN: And then—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The votes that you’re talking about, how did people cast their ballots? Were they paper ballots? Were they on scan machines? How exactly were the votes cast?

SARAH KINOSIAN: Yeah, so, the way that it—the way that the voting system works is, so people—I think that people cast their ballots on paper. But essentially what happens is, is there’s a table at each polling station, and there’s a sheet that tallies all of the votes from that station. And there’s different representatives from the parties at each of the tables. And the way that it works is, each table sends in the voting sheet to the electoral body, but then each of the representatives at the table also send their sheet to their party home base in Tegucigalpa. So what you’re getting now is—so you essentially have an electoral body count, and you also have each party that has its own count of these voting sheets that have tabulated all votes at a station. So that is why you’re getting discrepancies from what was sent to the electoral body versus what each party says, because they can each run their own counts from the sheets that they received from their representatives at each of the polling stations.

AMY GOODMAN: Allan Nairn, as we have Congressmember Jan Schakowsky on, how important, in the streets, is the U.S. Congress to the people of Honduras right now, as this election rolls out and the protests against electoral corruption and a rigged election play out? How much money has gone to Honduras, and what are people calling for around that?

ALLAN NAIRN: Well, historically, Honduras has been essentially an extension of the U.S. Pentagon and State Department. The current regime really dates back to the ’80s, when the U.S. was mounting the Contra attack against Nicaragua, established massive military bases in Honduras as the point of attack to go after what U.S. General Galvin described as “soft targets” in Nicaragua—namely, civilians. John Negroponte, who was the U.S. ambassador to Honduras at the time, presided over the standup of Battalion 3-16, which was essentially an army death squad, which did mass assassinations of Honduran dissidents and clergy, of activists, etc. After the 2009 coup, which at the time got de facto support from Hillary Clinton and President Obama, the death squads made a reappearance. And again, in the years since the ’09 coup, activists in the countryside have been in danger of assassination. The case of Berta Cáceres, the environmental activist, is the most famous, but there have been dozens and dozens of these.

I’ve talked, by now, to, oh, I’d say more than 70 soldiers and police in the past five days. And the majority of them had been trained in the U.S. And also, interestingly, significantly, I only found one, of all those I talked to, who is a real supporter of Hernández. The army is not allowed to vote. But if you ask them, “Well, how did your family back home vote?” the overwhelming majority say their families voted for Nasralla. And these are from troops and members of the police. And if that’s any indication, it gives a great credibility to the claim by the Nasralla opposition that they indeed would win in an accurate count.

The electoral commission, the other day, which is controlled by the government, came out and made a statement that essentially echoed the logic of the U.S. Supreme Court in the 19—in the 2000 Bush v. Gore decision, where they said—essentially said it would take too long to count the votes accurately. The people aren’t—people aren’t standing for that. And now the police are refusing, as well.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Allan, if we can, I’d like to—

ALLAN NAIRN: Last night, I was riding through the streets—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Allan, if we can, I’d like to bring in—

ALLAN NAIRN: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —Congresswoman Schakowsky once more. Could you—you mentioned the previous coup against Mel Zelaya, the continuing problems in Honduras, which seems to stand out among other Latin American countries in not being able to have free and fair elections. Could you talk about what kind of appetite there is among the Republicans in Congress to join with some of the Democrats to take a closer look at what’s happening in Honduras?

REP. JAN SCHAKOWSKY: Well, the Progressive Caucus has really taken the lead on this and has been very outspoken. And we are concerned about the fact that this administration has been such a friend of Honduras and has been so welcoming to Honduras and the Hernández government. We do need some Republican support and Republican interest. You know, there’s kind of short bandwidth right here in the Congress right now, not so much focusing on these critical issues of democracy in our Central American neighbors. So we’re going to be working on that.

But in the meantime, we’re really trying to raise this issue up so people understand that people are being—were being murdered in Honduras, not just over the election, but be a journalist, be a human rights defender, be a labor union activist, and your life is in danger in Honduras under this administration. And it is true that even in 2009, for about five minutes, the United States said that a coup had taken place, an illegal coup. And it didn’t take long then for that to be turned around and Honduras once again to be an ally of the United States, narcotrafficking, etc. And yet we have this very, very corrupt, anti-democratic president right now, and a chance perhaps, now with the police taking a different stance, to help restore true democracy in Honduras.

AMY GOODMAN: Congressmember Schakowsky, Reuters is reporting the State Department has certified the Honduran government has been fighting corruption and supporting human rights, clearing the way for Honduras to receive millions of dollars in U.S. aid. They saw a document dated November 28th that showed Secretary of State Tillerson certified Honduras for the assistance two days after the controversial presidential election, that’s been claimed by an ally of—of course, Juan Orlando Hernández—of Washington. The significance of this? Will you be allowing this to move forward? And this issue of the continued military support for Honduras?

REP. JAN SCHAKOWSKY: Well, we are clearly against. When I say “we,” those of us who are co-sponsoring the legislation for human rights in Honduras. Our demands are that we do not continue funding until there is some evidence that there’s actually an end to the human rights violations. We have put money into the military in Honduras, into the police, as well, into their training. The elite forces have been trained in the United States of America. How dare the secretary endorse Honduras and continued funding two days after an election that he knew at the time—he had to have known—was very controversial?

So we’re in great protest of what is happening. And so, you know, we’ve been involved in this for a long time, in the murder of the highest-profile human rights and indigenous people—person, activist Berta Cáceres. And we’re going to continue this fight and say, “No, this is not some kind of great guy,” as John Kelly calls him. This is someone, as president of Honduras, who is trying to actually collapse democracy there and take over that country in a very autocratic way.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I’m wondering, Sarah Kinosian, can you talk about the opposition? Because this was an alliance of political parties to the current president that were backing Nasralla. Could you talk about that coalition?

SARAH KINOSIAN: Yeah. In its simplest form, Salvador Nasralla had a party, the Anti-Corruption Party. He has paired with Mel Zelaya of the Liberal Party—or, LIBRE party, excuse me. And they formed together, and Salvador really needed the votes of Mel Zelaya. What I am hearing is that alliance, while it did give Salvador Nasralla the support that he needed to get this far with his support, it’s also presented problems because a lot of people are not distinguishing between Nasralla and Mel Zelaya. So what you’ll hear from a lot of Hernández supporters is two things: One, we’re going to have this—you know, either way, if it’s Zelaya or Juan Orlando, they’re going to try to keep staying in power because of 2009, or you hear this repeated line that the Hernández government is really trying to push out, which is Mel Zelaya is allied with Venezuela. And so you hear that concern a lot. If Nasralla wins, then Mel Zelaya will really be the one in power, and we’re going to end up like Venezuela.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Allan Nairn, what do you expect to see on the streets today as you’re out there speaking to people?

ALLAN NAIRN: Well, it’s possible that the revolt of the security forces will spread. On Sunday night—Sunday afternoon and Sunday night, I spoke to many soldiers, and a number of them were suggesting that they might defy orders. And I found it hard to believe at the time. In his street rally on Sunday, Nasralla made a direct call to the security forces to refuse to continue repression, to lay down their arms. It was reminiscent of—

AMY GOODMAN: We have 15 seconds.

ALLAN NAIRN: —what Archbishop Romero did in Salvador before he was assassinated. We’ll see how the army reacts now. And I think more people will take to the streets. This is really in the hands of the U.S. If the U.S. tells the Salvadoran army to cut it out, if they tell Hernández to allow an honest count, they will comply, because they are clients of Washington. And this goes back, directly back, to the White House, to General Kelly, as Representative Schakowsky said. It’s in Kelly’s hands. He can bring this to a peaceful, democratic conclusion, if he chooses.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there.

ALLAN NAIRN: If not, there will be more bloodshed.

AMY GOODMAN: Journalist Allan Nairn and Sarah Kinosian in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, and Congressmember Jan Schakowsky.

Media Options