Guests

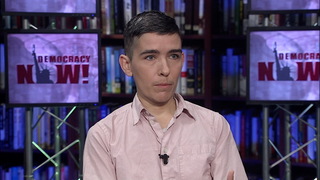

- Lewis Wallacefired from the national radio outlet Marketplace after posting a blog post on the website Medium about journalistic neutrality and the challenges of being a transgender journalist in the era of “alternative facts.”

Watch Part 2 of our interview with Lewis Wallace, who was fired from the public radio show “Marketplace” after he published a blog post about journalistic neutrality. Wallace talks about his career in journalism, and reads his post, Objectivity is dead, and I’m okay with it, in which he questions whether people who hold “morally reprehensible” positions, such as supporting white supremacy, can be covered objectively, and argues journalists shouldn’t care if they are called “politically correct” or “liberal.”

Watch Part 1–Meet Lewis Wallace: Trans Reporter Fired for Writing About Journalistic Integrity in Trump Era

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we turn to Part 2 of a conversation with a reporter who wrote a blog post about journalistic neutrality under President Donald Trump and found himself out of a job. Until last week, Lewis Wallace was the only out transgender reporter at the public radio show Marketplace. Then he published a blog post on the website Medium about journalistic neutrality and the challenges of being a transgender journalist who covers the current administration. Under the headline “Objectivity is dead, and I’m okay with it,” he questioned whether people who hold, quote, “morally reprehensible” positions, such as supporting white supremacy, can be covered objectively. And he argued journalists shouldn’t care if they’re called “politically correct” or “liberal.” He also wrote, quote, “After years of silence/denial about our existence, the media has finally picked up trans stories, but the nature of the debate is over whether or not we should be allowed to live and participate in society, use public facilities and expect not to be harassed, fired or even killed,” unquote. Well, Marketplace said Wallace’s blog post violated its code of ethics. It suspended him for writing it and asked him to take it down. When Lewis later republished it, he was fired.

Well, for more, Lewis Wallace joins us here in our New York studio for a continuation of the conversation we began on Democracy Now!

So, why don’t you tell us about the piece that you originally wrote. It was headlined?

LEWIS WALLACE: “Objectivity is dead, and I’m okay with it,” which I will cop to click bait on the headline, you know, trying to grab people’s interest with that. But I also believe that, and I think a lot of journalists believe that we’re past the point, and have been for quite a while, where our audiences, readers, listeners, expect that we are truly objective and neutral people, and want us to sort of pretend that we’re not bringing a perspective to the work that we do. So the argument wasn’t so much, you know, we should all do advocacy journalism or everyone needs to become an opinion writer, so much as a broader discussion about the kind of urgent need to know what we stand for as journalists in this time period, where our moral center is, which sorts of behaviors and activities we are going to target as inherently unfair, even if legal. And I think, you know, there are real concerns there under an administration that’s perfectly willing to propagate—propagate lies and talk about concepts like alternative facts. So the reason I wrote the piece was because of a real sense of urgency around how we approach our work as journalists, and I really wanted to carry on that conversation. And I think being a trans person just kind of has brought me to a particular perspective on these issues, because there are certain things that I’ve never been able to be neutral on, because I wouldn’t have been able to live and survive. And I don’t think I should have to pretend that that’s not the case, in order to do my job.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let me read what Marketplace wrote to us when we reached out to them to be on the show. This is the director of communications, Angie Anderson, who responded with the following statement: “The broader issue around journalistic ethics is an ongoing one for the industry, with each media entity needing to define what it means for how they report. For Marketplace, it’s very clear. We are committed to raising the economic intelligence of all Americans. We accomplish that with independent and objective reporting that is based on facts, pursues the truth, and covers what’s happening in a fair and neutral way. Our journalists’ mission is to be honest, impartial, nonpartisan and independent in their work. Our team is a diverse group of professionals who have committed to that code of ethics. We don’t discuss personnel matters about current or former employees.” That’s the statement they sent us. So, talk about the chronology of events—the piece that you wrote, and then what happened?

LEWIS WALLACE: I put it up on my Medium page, which at the time did not have a lot of followers and, you know, was just kind of a personal reflection that I was hoping like people who know me and follow me would read. That was on Wednesday of last week. A couple hours later, I got a call from the managing editor and executive producer of the show, who went over some points in the ethics code that they felt that I had violated.

AMY GOODMAN: And what exactly did they say you violated? What part of your piece?

LEWIS WALLACE: The concern was, I think, primarily about perception. There is a part of the Marketplace ethics code that talks about not doing anything that could be perceived as compromising Marketplace's impartiality. And so, that was, I think, at the core of their concerns. They told me that Marketplace does believe in objectivity and neutrality. Not to spilt hairs there, but the ethics code uses the term “impartiality,” neither of those other two terms. And I actually am quite a bit more comfortable with the concept of impartiality. And, of course, I signed on and agreed to this ethics code when I agreed to take the job, so I knew exactly what I was signing on for, and I genuinely didn't think that I was in violation of it.

AMY GOODMAN: Because? Explain why.

LEWIS WALLACE: Because I think that objectivity and neutrality really are up for debate in our industry right now, and that for me to bring kind of my unique voice as a trans person, also just as a person with all my other life experiences and ways that I look at things, questions that I ask, is inherently not neutral. That doesn’t mean that I’m doing stories where I take a side or where I’m partial to one source over another. But neutrality, to me, is a different concept.

And so, I was eager to carry on that conversation, you know, both with my colleagues, other journalists at Marketplace, who are really smart people and are also interested in these conversations. However, before kind of having the opportunity to do that, I was suspended from my job on air. I was working for the Marketplace Morning Report as a daily news reporter, going on air every morning once or twice, doing daily stories on tight deadlines. I love that work. I was really good at it. And being punished in that way didn’t sit well with me.

So, initially, I took the post down. I thought about it, slept on it for another night. And the next day, I sent—I made a very personal decision, sent a fairly emotional letter to the people who had suspended me, and said, “I’ve decided to put this piece back up tonight. Here’s why.” Some of the issues I addressed were my disagreement with them on the ethic codes itself and that I had violated it, perceived inconsistency in the enforcement of that code, and then, I think, more importantly, the urgency that I had around we need to be having this conversation, and we should be having it out in the open.

I invited Marketplace to respond to my post publicly, or maybe even to put another one of my colleagues up to writing a rebuttal or a response. I thought that would be an amazing way to build the public trust and kind of get people interested in what we’re doing, you know? We’re real people. We’re having these conversations in our newsroom. We’re a diverse newsroom. We’re concerned about these things, and that we could show people that by carrying on the conversation openly.

So, that was the invitation that I extended, and I thought that would have been a great way to kind of transparently address how complicated these issues are. None of us have answers, including, of course, me. But instead, I didn’t hear back from that letter. I reposted the piece. And on Monday, I was fired.

AMY GOODMAN: On Medium?

LEWIS WALLACE: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: So I want to read a comment from Felix Salmon of Fusion about what happened to you and Marketplace's response: quote, “Let's be clear about the message that such a policy sends to any genuinely diverse workforce. It says that who you are matters less than what you say; it says that diversity of voices must always be constrained by a blanket refusal to countenance charged political expression.” That’s Felix Salmon in Fusion, responding to your firing. Lewis Wallace, your response?

LEWIS WALLACE: I think he’s really hitting on something that a lot of—you know, I should just speak for myself as a transgender person, that I feel like I understand very personally as a transgender person and just from my life experience this idea that one can separate one’s identity from sort of being politicized has never been real for me. So, and it wasn’t my choice that my identity—and continues not to be my choice that my identity is politicized. That’s something that other people are doing around trans people. And there’s a debate about whether we should have access to extremely basic things, like restrooms and physical safety and healthcare. And, you know, of course, I need to use the bathroom. I want to be alive. I need healthcare. I’m not going to sort of fuss over whether that’s a real debate. It’s not, for me. That’s how I’ve had to survive. And I think most people who have kind of been through that understand that if somebody else politicizes your identity, it’s not your fault, and you have to stand up for yourself and keep moving. And, of course, I’m doing that every day sort of implicitly as I go out in the field and do my job as a journalist.

I think to talk about it openly was kind of all I did in my blog post. And it is unfortunate that news organizations right now are sending a message to—that some news organizations are sending a message to their employees who are part of marginalized or oppressed communities or identities: You should be afraid of talking about this, and we are afraid of the implications of that. You know? I’m not afraid of being called politically correct, because I have been called that many times just because of who I am and advocating for myself. I don’t care. And I don’t think any of us should care. I think we should focus on telling the truth and exposing lies and corruption and, you know, looking at how power works in this country. And I think that’s what I was doing in my stories on Marketplace. That’s what all the journalists there are doing. You know, it’s a great show, and I really actually didn’t think that any of these issues were going to be so controversial.

AMY GOODMAN: Lewis, can you talk about your background, how you got started in journalism?

LEWIS WALLACE: Yeah. So, I had been a community organizer, and I was brought into radio, public radio journalism, through a fellowship at WBEZ in Chicago. That was for people who did community work to kind of come in and bring more diversity of voices into that local station. And that’s a big and pretty innovative public radio newsroom that works really hard to be in the communities that it’s reporting in.

And then I went from there to a pretty similar organization, but really, really small, called WYSO in Yellow Springs, Ohio. And that’s like, for such a tiny place, this kind of amazing, innovative community project, teaching hundreds of people in that community to make their own radio stories, bringing together voices that are usually kind of separated by the geography of that region, because it’s a very, you know, sort of segregated and highway-based area of Southwest Ohio, a sort of rural-suburban-urban combination around Dayton.

We did a series and reported from within a prison. We did an hour-long documentary, award-winning, about the Black Lives Matter movement in this rural part of Ohio. There was a murder of a young black man inside of a Wal-Mart by white police officers there four days before Michael Brown was killed. And the protest movement grew sort of exponentially, again, in this very, very small community. And we covered that really closely, kind of play by play over a couple of years, and did a lot of work that I was really proud of around that.

And that station was known for being super community-based and sort of going above and beyond to represent the communities that we worked in. So I guess I had this pretty like rosy idea of the possibilities and the opportunities of being in public radio and kind of the funding model. You know, we’re not funded by advertisements. We’re funded by listeners, and that means we can always be working harder to represent diverse communities. And like I was excited about that stuff, still am.

AMY GOODMAN: So you joined Marketplace earlier last year?

LEWIS WALLACE: Mm-hmm. I went from—

AMY GOODMAN: Have you been criticized for your work there?

LEWIS WALLACE: No, I—no, I’ve done a lot of work that I’m really proud of there. And I’ve never had the feedback that it was sort of biased or partial or in any way not up to ethical standards. And I—you know, editorially, I felt like I was really aligned with the people that I worked with there around—like we do get to have a voice, and we do bring sort of our own unique perspective and questions to this work.

AMY GOODMAN: And how your post fits into that?

LEWIS WALLACE: So, to me, the post that I wrote was just spelling out the way that I already work, you know, being transparent about sort of who I am within that. But the way that I work, my journalism itself, had never caused any problems around sort of neutrality. It was being honest about the way that I’m working. And I think one of the parts that I’ve heard is more controversial for people is that I talk about white racial superiority, white supremacy, and that, you know, I find those ideas to be reprehensible and false. That doesn’t mean that I don’t go and talk to people who hold white supremacist views or support white supremacist policies, and listen extremely carefully to what they have to say. And I’ve done multiple stories for Marketplace that have really kind of remarkable, remarkably honest commentary from people who have supported white supremacist policies of Donald Trump and his followers. And so, I never advocated, “Oh, we shouldn’t listen to those folks.” But I have advocated, and will continue to, that we need a frame in order to understand what questions to ask and how we’re going to decide what stories to tell. And for me, that frame is one that is skeptical of any policy that upholds white supremacy.

AMY GOODMAN: How have your colleagues responded?

LEWIS WALLACE: My colleagues sort of across public radio, you know, around the country have been really amazing. The thing that just makes me sad is how many people I’ve heard from who have said, “We want to be having these conversations in our newsrooms, and we need to be, but people are afraid to bring it up.” And I’ve heard from multiple people that they’re going to take my blog post, or they already have, to their managers or their editors and use it to force a conversation around issues that everyone is really concerned about.

You know, I mean, I think even there was this sort of moment with the Women’s March a couple weeks ago where a lot of journalists secretly went to the Women’s March and didn’t tell their bosses, right? And so, like that’s happening, because people are feeling like we’re in a watershed moment where the sort of basic institutions that protect the work that we do as journalists, that protect our lives as, you know, transgender people or women or immigrants or people of color, all of that is being threatened. And, I mean, who isn’t thinking about what’s the right thing to do in this moment, including journalists? And the idea that journalists are going to secretly go to demonstrations, instead of feeling comfortable that they can openly have those conversations in their newsrooms without getting fired, really makes me angry. You know?

I think we need sort of the courage and transparency to have those conversations openly. And the idea that I’ve heard from all over the country that people want to be having those conversations and they’re afraid for their jobs, I just—that’s been eye-opening for me and eye-opening as to why it was so important to kind of push this conversation now.

AMY GOODMAN: Lewis Wallace, would you read your piece for us on air?

LEWIS WALLACE: Sure. “Objectivity is dead, and I’m okay with it.”

Like a lot of people, I’ve been losing sleep over the news of the last week. As a working journalist, I’ve been deeply questioning not just what our role is in this moment, but how we must change what we are doing to adapt to a government that believes in, quote, “alternative facts” and thrives on lies, including the lie of white racial superiority.

I also have the great privilege of working for a public media organization, one whose mission is to serve our listeners as opposed to corporations or the cult of clicks and shares.

One of the diciest issues as we reconsider our role as journalists in this moment is that of “objectivity.” Some argue that if we abandon our stance of journalistic neutrality, we let the “post-fact” camp win. I argue that our minds — and our listeners’ and readers minds — are stronger than that, strong enough to hold that we can both come from a particular perspective, and still tell the truth. And I have the sense that this distinction is important in this moment, because we are going to have to fight for and defend what it means to serve the public as journalists.

So, a few thoughts on objectivity in this political moment:

1. Neutrality isn’t real: Neutrality is impossible for me, and you should admit that it is for you, too. As a member of a marginalized community (I am transgender), I’ve never had the opportunity to pretend I can be, quote, “neutral.” After years of silence and denial about our existence, the media has finally picked up trans stories, but the nature of the debate is over whether or not we should be allowed to live and participate in society, to use public facilities and expect not to be harassed, fired or even killed. Obviously, I can’t be neutral or centrist in a debate over my own humanity. The idea that I don’t have a right to exist is not an opinion, it is a falsehood. On that note, can people of color be expected to give credence to, quote, “both sides” of a dispute with a white supremacist, a person who holds unscientific and morally reprehensible views on the very nature of being human? Should any of us do that? Final note here, the, quote, “center” that is viewed as neutral can and does shift; studying the history of journalism is a great help in understanding how centrism is more a marketing tactic to reach broad audiences than actual neutrality. Many of the journalists who’ve told the truth in key historical moments have been outliers and members of an opposition, here and in other countries. And right now, as norms of government shift toward a “post-fact” framework, I’d argue that any journalist invested in factual reporting can no longer remain neutral.

2. It matters who is making editorial decisions: I think marginalized people, more than ever now, need to be at the table shaping the stories the fact-based news media puts out. I think people crave the honesty, the uniqueness, the depth that comes out of bringing an actual perspective to our work. And my experience is that audiences want us to be truthful and fair, but they don’t want us to be robots. And they don’t want us to all be white and male, a situation which creates its own sort of bias toward the status quo, male power and white racism.

3. We can (and should) still tell the truth and check our facts: The job of storytelling, of truth-telling, is not going away. But it is getting harder and more complex, in the face of unknowable datasets, lying federal leaders, Facebook algorithm dominance and a changing but also opaque market for online news that tends to bring the foamiest of fluff to the top and confuses even the most savvy consumers. All of that said, the people consuming news are savvy. They know that news is curated and complex; that the editorial choice of what to report and how to report it is always a subjective one; that facts are real, but so are priorities and perspective. I think we are past the point where they expect us to speak to a fictitious and ever-shifting center in order to appear “neutral.” In other words, we can check our facts, tell the truth, and hold the line without pretending that there is no ethical basis to the work that we do.

4. Journalists should fight back: As the status quo in this country shifts, we must decide whether we are going to shift with it. It seems clear that these shifts will not benefit those of us in the industry who care about truth-telling and about holding power accountable. Will we shift toward climate denial? Will we make space for demonization of Muslims and Mexicans and, quote, “Chicago”? Will we give voice to “alternative facts”? Instead of waiting and seeing, reacting as journalists are arrested, freedoms of speech curtailed, government numbers lied about, I propose that we need to become more shameless, more raw, more honest with ourselves and our audiences about who we are, and what we are in this for. To call a politician on a lie is our job; to bring stories of the oppressed to life is our job; to represent a cross-section of our communities is our job; to tell the truth in the face of, quote, “alternative facts” and routine obscuring is our job; and we can do all that without promoting the male-centric and whitewashed falsehood of objectivity. I also believe that by claiming these stances, we strengthen our position against those who would try to overwhelm and distract us with made-up stories. But we need to admit that those who oppose free speech, diversity and kindergarten-level fairness are our enemies.

5. Get our sense of purpose, for real: We need to know why we tell these stories in order to continue to tell them well. And to fully represent our communities in their diverse truths in this day and age is a political statement, whether we like it or not. Rather than back off of those goals, we should double down. We will be called politically correct, liberal or leftist. We shouldn’t care about that nor work to avoid it. We don’t have time for that. Instead, we should own the fact that to tell the stories and promote the voices of marginalized and targeted people is not a neutral stance from the sidelines, but an important front in a lively battle against the narrow-mindedness, tyranny, and institutional oppression that puts all of our freedoms at risk.

I’m genuinely curious what people think about these ideas and would love to hear your thoughts. Like all of us, I’m just trying to figure it out, day in and day out. But I’m also not willing to accept obsolescence.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Lewis Wallace reading his piece, “Objectivity is dead, and I’m okay with it.” After posting it publicly, he was fired by Marketplace. Finally, Lewis, what are your plans now?

LEWIS WALLACE: I want to tell you my fantasies instead of my plans. I want to write a book about the history of objectivity in journalism. I want to start an amazing new news organization focused on telling the truth, reporting the facts on daily news centered in the Deep South and the Rust Belt. And I want to keep being a field reporter, because that’s actually what I love and I’m good at.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, thanks so much for sharing your piece and your thoughts with us today on Democracy Now! This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options