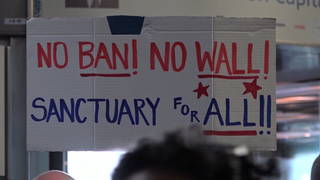

An appeals court is expected to rule as early as today on President Trump’s ban on refugees and people from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States. On Wednesday morning, Trump accused the judges on the court of being “so political” and described the legal process as “disgraceful.” For more updates on the legal fight over the executive order, we speak with Hina Shamsi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project. Although she is a legal permanent resident of the United States, Shamsi was stopped and questioned about her Pakistani citizenship and her work with the ACLU, when she flew back into the country last week.

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals is expected to rule as early as today on President Trump’s temporary travel ban on refugees and people from seven Muslim-majority countries. On Tuesday, a three-judge panel heard arguments from lawyers representing the Justice Department and the state of Washington, which sued Trump over the order. On Wednesday morning, Trump accused the judges of being, quote, “so political” and described the legal process as “disgraceful.”

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: And I want to tell you, I listened to a bunch of stuff last night on television that was disgraceful. It was disgraceful. … So, I think it’s sad. I think it’s a sad day. I think our security is at risk today. And it will be at risk until such time as we are entitled and get what we are entitled to as citizens of this country, as chiefs, as sheriffs of this country.

AMY GOODMAN: To talk more about the executive order, we’re joined by Hina Shamsi. In addition to being the director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project, she’s also been personally impacted by Trump’s executive order. Although she is a legal permanent resident, Hina was stopped and questioned about her Pakistani citizenship and her work with ACLU, when she flew back into the country last week.

So, Hina, let’s start there. What happened to you? Where did you fly in? What were you asked?

HINA SHAMSI: Well, Amy, I was in the island nation of Dominica for client meetings and depositions in our lawsuit on behalf of torture victims seeking accountability from the two CIA contractors who are behind the torture program there. And I was—

AMY GOODMAN: Mitchell and Jessen?

HINA SHAMSI: Mitchell and Jessen, yes, Doctors Mitchell and Jessen. And I was coming back from that set of meetings and the deposition, and transiting through San Juan, Puerto Rico. When I was going through immigration, it seemed like an immediate flag went up, and I was pulled into what’s called secondary screening by a Customs and Border Protection, or CBP, agent.

Now, I want to emphasize something, which is that, you know, what happened to me is nothing compared to the suffering and hardship that people impacted by the executive order, Muslim ban, are going through and have gone through. To me, this was, though—and I usually don’t write about things that are so personal, but it said something to me about the climate in these times. And the kinds of questions that were raised were ones that I have never experienced in over 25 years of travel into and out of this country, over 10 years of work for the ACLU and other rights groups, and travel in that context.

AMY GOODMAN: You went to college here?

HINA SHAMSI: I came here to go to college.

AMY GOODMAN: Where did you go?

HINA SHAMSI: Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. You know, worked here, law school, all of that. And never have I experienced anything like this, because—it started out with something absolutely legitimate, which is, you know, “Where were you, and what were you doing?” Then, as soon as I said that I work for the American Civil Liberties Union and I was traveling for work, there was an entire series of questions that began with “Why would someone working for an organization, or this organization with 'American' in its name, have this passport?” And the agent had my Pakistani passport in his hand. Or, “Why would someone working for an organization with 'American' in its name be representing people who are not citizens?” And when I was explaining that my work is, and long has been, as a U.S.-trained lawyer, sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution, which is what I work to do at the ACLU, one response was: “Well, if you’re working for organization with 'American' in its name, and your focus is the U.S. Constitution, why are you traveling abroad so much?” And so, over and over again, I tried to explain my work, my focus on U.S. Constitution and treaties, and the fact that I was traveling for this work. And amongst the responses were: “When you’re at meetings and talks abroad, do you talk about U.S. law, or do you talk about the laws of other countries?” Now, none of this is remotely relevant to what might be the legitimate question that CBP can ask, which is, you know, “What were you doing?” and “What’s your status?” and “Can you legitimately come into the United States?” And it really was a tenor of suspicion, of emphasis on American and what constitutes American, in a way that—that I hadn’t seen before.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And you were taken to secondary screening, as you said. Now, there were a very large number of people who were subjected to secondary screening from Pakistan and from other countries right after 9/11. But you say this has never happened to you. But in your view, how does what’s happening now compare to what happened immediately following 9/11, and which went on for some time, for people who were, like you, legal permanent residents of the U.S., but had passports from Muslim-majority countries?

HINA SHAMSI: Right. And indeed, immediately after 9/11, there was a whole series of questioning for people with—you know, legal permanent residents with Pakistani nationality and nationality of other majority-Muslim countries, as well. And I’ve certainly represented people who have been unjustifiably questioned based on their work or their, you know, citizenship or their studies. And perhaps it’s remarkable that I’ve not been questioned before. You know, I sometimes—I sometimes think that. But it is also true that in all my years of my travel, when I was challenging Bush administration policies of torture and Guantánamo and other human rights abuses, or travel during the Obama administration, when I’ve been challenging unlawful targeted killing, anti-Muslim discrimination, illegal spying, it hadn’t—people hadn’t questioned me about—in this manner, which seemed to sort of convey a questioning of identity and even a sense of loyalty here. That just hadn’t happened before. And so, you know, it’s hard to generalize, and I’m reluctant to do that based on my single experience, but we’ve certainly heard of other people, citizens and LPRs of Pakistan and other majority-Muslim countries, being questioned even recently. And so, I worry deeply about the message that has been sent from the top, this anti-Muslim animus, and the ways that it is being heard by government officials and government agents who are able to exercise this power at the border and other places.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you if they asked you to give up your social media passwords or anything like that.

HINA SHAMSI: They did not. They did not ask me that, although they’ve been asking—there was concern that they’ve been asking other people that recently.

AMY GOODMAN: Right, because CNET is reporting visitors to the U.S. might be asked to relinquish their social media passwords to border agents as part of an attempt to tighten security checks. Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly was being questioned by the Homeland Security Committee on Tuesday, and he said, “We want to get on their social media, with passwords: What do you do? What do you say?” They asked him—he responded, “If they don’t want to cooperate, then you don’t come in.” What are your rights, both as American citizens, as permanent residents like you, and as people with visas who are coming into this country?

HINA SHAMSI: So this is a hotly contested area right now. And it is—first of all, as a citizen, there’s a right to re-enter the country. As a legal permanent resident, you can get questioned, and we generally advise people to answer questions and to know that if they’re not responding to questions or refusing to provide information, that they might face delays. But this is a situation in which people can be very vulnerable and feel very vulnerable at the border. And when there were proposals during the Obama administration to ask people for their social media handles and their passwords and so on, we and other organizations wrote in comment to criticize and question these proposals: How specifically are you going to implement this? For what purpose? Are you going to retain this information? What are you actually going to do about it? And we’ve not—we’ve not really received any satisfactory responses yet. And so this is something that we are watching very, very closely, indeed.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And do you know if there are human rights lawyers or organizations who have already issued this inquiry to the Trump administration, since there are reports it’s already happening?

HINA SHAMSI: Yes, and I think people are questioning and asking what’s going on and what are you planning on doing—questions that we’ve had previously and that are even more acute now.

Media Options