Guests

- Jane Mayerstaff writer at The New Yorker. Her latest piece is headlined “The Reclusive Hedge-Fund Tycoon Behind the Trump Presidency: How Robert Mercer exploited America’s populist insurgency.” Her book, Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, has just come out in paperback with a new preface on Trump.

Full interview with The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer about her new article, “The Reclusive Hedge-Fund Tycoon Behind the Trump Presidency: How Robert Mercer Exploited America’s Populist Insurgency.” The piece looks at Robert Mercer, the man who is said to have out-Koched the Koch brothers in the 2016 election.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: From Pacifica, this is Democracy Now!

JANE MAYER: The history of the country has been, you know, of certainly big money players. What you’ve got here is almost like a third party that is the money party. It’s a conservative outside pressure group that is acting as a force field, pulling the Republican Party, particularly, to the right.

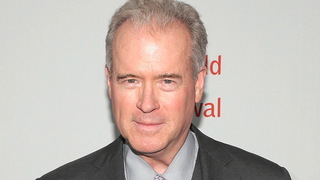

AMY GOODMAN: Today, Jane Mayer on Robert Mercer, the reclusive hedge fund billionaire who helped Trump win the White House. Some say he and his daughter Rebekah out-Koched the Koch brothers. For years, the Mercers bankrolled Steve Bannon’s Breitbart News and other right-wing organizations. Now, allies of the Mercers control the White House. We’ll speak with investigative reporter Jane Mayer about her new piece in The New Yorker and hear excerpts of one of Robert Mercer’s only public appearances.

ROBERT MERCER: I wondered, “What in the world am I going to say?” I left IBM Research 20 years ago, and I really have not paid any attention to the world of linguistics or to IBM since then. And I can’t really talk about what I do now, so…

AMY GOODMAN: We’ll also look at dark money’s role in the confirmation process of Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch.

All that and more, coming up.

This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And I’m Nermeen Shaikh. Welcome to our listeners and viewers around the country and around the world.

We turn now to look at the man who is said to have out-Koched the Koch brothers in the 2016 election. His name is Robert Mercer, a secretive billionaire hedge-fund tycoon who, along with his daughter Rebekah, is credited by many with playing an instrumental role in Donald Trump’s election.

Trump’s chief strategist, Steve Bannon, said, quote, “The Mercers laid the groundwork for the Trump revolution. Irrefutably, when you look at donors during the past four years, they have had the single biggest impact of anybody, including the Kochs.” Before Bannon and Kellyanne Conway joined the Trump campaign, both worked closely with the Mercers. The Mercers bankrolled Bannon’s Breitbart News, as well as some of Bannon’s film projects. Conway ran a super PAC created by the Mercers to initially back the candidacy of Ted Cruz.

The Mercers also invested in a data mining firm called Cambridge Analytica, which claims it has psychological profiles of over 200 million American voters. The firm was hired by the Trump campaign to help target its message to potential voters.

While the Mercers have helped reshape the American political landscape, their work has all been done from the shadows. They don’t speak to the media and rarely even speak in public.

AMY GOODMAN: During the entire presidential campaign, they released just two statements. One was a defense of Donald Trump shortly after the leak of the 2005 Access Hollywood tape that showed Trump boasting about sexually assaulting women. The Mercers wrote, quote, “We are completely indifferent to Mr. Trump’s locker room braggadocio.” They went on to write, “America is finally fed up and disgusted with its political elite. Trump is channeling this disgust and those among the political elite who quake before the boombox of media blather do not appreciate the apocalyptic choice America faces on November 8th. We have a country to save and there is only one person who can save it. We, and Americans across the country and around the world, stand steadfastly behind Donald J Trump.” Those were the words of Robert and Rebekah Mercer one month before Trump won the election.

Since the election, Rebekah Mercer joined the Trump transition team, and Robert Mercer threw a victory party of sorts at his Long Island estate. It was a hero and villain’s costume party. Kellyanne Conway showed up as Superwoman. Donald Trump showed up as himself.

To talk more about the Mercers, we’re joined now by Jane Mayer, staff writer at The New Yorker, her latest piece headlined “The Reclusive Hedge-Fund Tycoon Behind the Trump Presidency: How Robert Mercer exploited America’s populist insurgency.” Jane is also author of Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right, which just came out in paperback.

Jane Mayer, welcome back to Democracy Now! The beginning of the piece talks about a former colleague of Mercer’s saying, “In my view, Trump wouldn’t be president if not for Bob.” Explain who Robert Mercer is.

JANE MAYER: Well, he’s a, as you’ve mentioned, a New York hedge-fund tycoon. He’s a computer scientist, a kind of a math genius and uber-nerd, who figured out how to game the stocks and bonds and commodities markets by using math. He runs something that’s kind of like a quant fund in Long Island, and it’s called Renaissance Technologies. He’s the co-CEO. And it just mints money. So he’s enormously wealthy. He earns at least $135 million a year, according to Institutional Investor, probably more.

And what he’s done is he has tried to take this fortune and reshape, first, the Republican Party and, then, America, along his own lines. His ideology is extreme. He’s way far on the right. He hates government. Kind of—according to another colleague, David Magerman, at Renaissance Technologies, Bob Mercer wants to shrink the government down to the size of a pinhead. He has contempt for social services and for the people who need social services.

And so, he has been a power behind the scenes in Trump’s campaign. He kind of rescued Trump’s campaign in the end, he and his daughter. And, you know, most people think Trump was the candidate who did it on his own, had his own fortune, and he often boasted that he needed no help and had no strings attached, and he was going to sort of throw out corruption. And, in fact, there was somebody behind the scenes who helped enormously with him.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about that moment, when you talk about them saving Donald Trump, which has become particularly relevant today. This was the time that Manafort was forced out as the campaign manager for Donald Trump. The campaign was in disarray. He was being forced out because of his ties to Ukraine and Russia and the money that was being revealed that he might or might not have taken. So, take it from there.

JANE MAYER: Well, right. And this was—really, Trump’s campaign was—it was floundering. It was in August, and there was headline after headline that was suggesting that Paul Manafort, who had been the campaign manager, had really nefarious ties to the Ukrainian oligarchs and pro-Putin forces. And it was embarrassing. And eventually, after a couple days of these headlines, he was forced to step down.

And the campaign was, you know, spinning in a kind of a downward spiral, when, at a fundraiser out in Long Island, at Woody Johnson’s house—he’s the man who owns the Jets—Rebekah Mercer, the daughter of this hedge-fund tycoon, Bob Mercer, sort of cornered Trump and said, “You know, we’d like to give money to your campaign. We’ll back you, but you’ve got to try to, you know, stabilize it.” And basically, she said, “And I’ve got just the people for you to do the job.”

And they were political operatives who the Mercer family had been funding for a couple of years, the main one being Steve Bannon, who is now playing the role to Trump—he’s the political strategist for Trump—that’s the role he played for the Mercer family prior to doing it for Trump. So, these are operatives who are very close to this one mega-donor. The other was Kellyanne Conway, who had been running this superfund, as you mentioned in your introduction, for the Cruz campaign, that was filled with the money from the Mercers. And so she became the campaign manager. Bannon became the campaign chairman. And a third person, David Bossie, whose organization Citizens United was also very heavily backed by the Mercer family, he became the deputy campaign manager. So, basically, as Trump’s campaign is rescued by this gang, they encircle Trump. And since then, they’ve also encircled Trump’s White House and become very key to him. And they are the Mercers’ people.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Jane Mayer, Rebekah Mercer, whom you mentioned, is known—described as “the first lady of the 'alt-right.'” Now, you tried to get Rebekah and Robert Mercer to speak to you for this piece. What response did you get?

JANE MAYER: Oh, I mean, it was hopeless, clearly, from the start. They have nothing but disdain for, you know, the mainstream media. Robert Mercer barely speaks even to people who he works with and who know him. I mean, he’s so silent that he has said often that he—or to a colleague, he said once—I should correct that—that he much prefers the company of cats to humans. He goes through whole meetings, whole dinners, without uttering a word. He never speaks to the media. He’s given, I think, one interview I know of, to a book author, and who described him as having the demeanor of an icy cold poker player.

His daughter, Rebekah Mercer, who’s 43 and has also worked at the family’s hedge fund a little bit and is a graduate of Stanford, she’s a little more outspoken. She has been in fundraising meetings on the right. She has spoken up—and very loudly and irately, actually. But she doesn’t speak to the press. And so, I had very little hope that they would.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about when they first met, the Mercers, Robert and Rebekah Mercer, first met Andrew Breitbart, and what that progression was and how they came to be linked up with Bannon?

JANE MAYER: Well, sure. The Mercer family, Robert and his daughter Rebekah, met Andrew Breitbart back—I think it was late 2011 or early 2012, speaking at a conference of the Club for Growth, another right-wing group. And they were completely taken with Andrew Breitbart. He was pretty much the opposite kind of character from Bob Mercer. Breitbart was outspoken and gleefully provocative and loved to offend people and use vulgar language just to catch their attention. And you’ve got this kind of tight-lipped hedge-fund man from the far right who just fell for Breitbart big time.

And he—mostly what he was captivated by, I think, was Breitbart’s vision, which was, “We’re going to”—he said, “Conservatives can never win until we basically take on the mainstream media and build up our own source of information.” He was talking about declaring information warfare in this country on fact-based reporting and substituting it with their own vision. And what he needed, Breitbart, at that point, was money. He needed money to set up Breitbart News, which was only just sort of a couple of bloggers at that point.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about Breitbart News, about what the “alt-right” represented, whether we’re talking about anti-Semitism or white supremacy, and why they were attracted to this.

JANE MAYER: Well, I mean, you know, it changed. What happened was—I mean, it started as a—Andrew Breitbart had helped The Huffington Post get set up. And his idea was that he was going to launch The Huffington Post of the right. And so, he was setting it up, and his very close friend was Steve Bannon. And Bannon had been in investment banking. So Bannon got the Mercers to put $10 million into turning this venture into something that was really going to pack a punch. And they were just about to launch it in a big day—big way. They were a few days away from it, when Andrew Breitbart died. That was in March of 2012. He was only 43, and he had a sudden massive heart attack. And so, this operation was just about to go big. It was leaderless. And that’s when Steve Bannon stepped in and became the head of Breitbart News.

And in Bannon’s hands, it became a force of economic nationalism and, in some people’s view, white supremacism. It ran, you know, a regular feature on black crime. It hosted and pretty much launched the career of Milo Yiannopoulos, who’s sort of infamous for his kind of juvenile attacks on women and immigrants and God knows what. You know, just it became, as Bannon had said, a platform for the “alt-right,” meaning the alternative to the old right, a new right that was far more angry and aggressive about others, people who were not just kind of the white sort of conservatives like themselves.

AMY GOODMAN: So they made a $10 million investment in Breitbart. They owned it—

JANE MAYER: A 10 million.

AMY GOODMAN: —co-owned it.

JANE MAYER: They became the sponsors, really, behind it. And it’s interesting to me that—one of the things I learned was that Rebekah Mercer, this heiress, who’s had no experience in politics, is so immersed in running Breitbart News at this point. I mean, she—her family is the money, big money, behind it. That she reads every story, I’m told, and flyspecks, you know, typos and grammar and all that kind of thing. I mean, there is a force behind Breitbart News that people don’t realize, and it’s the Mercer family. So, anyway, it became very important, increasingly, on the fringe of conservative politics, because it pushed the conservatives in this country towards this economic nationalism, nativism, anti-immigration, pro-harsh borders, anti-free trade, protectionist. And it spoke the language of populism, but right-wing populism.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Jane Mayer, I mean, as you’ve said, one of the things that has made the Mercers so successful in their political interventions is precisely this, the way in which they’ve invested in an alternative media and information network, of which Breitbart is, of course, a very significant part. But can you also talk about the Government Accountability Institute, which you discuss in your piece?

JANE MAYER: Sure. I mean, and this was, you know, very much a design. You’ve got this family with all the money in the world, wanting to change American politics. And they hadn’t been very effective in their earlier efforts at this, until they joined forces with Steve Bannon, who’s a very sort of farsighted strategist who kind of sees the big picture and understands politics. And so, he very much focused their efforts on this information warfare, first with Breitbart, $10 million into that. And then, after 2012, when the Mercers were very disappointed that Obama got re-elected, at Bannon’s direction, they started to fund a brand-new organization called the Government Accountability Institute. It’s based in Tallahassee. It’s small. It’s really a platform for one major figure, Peter Schweizer, who is a conservative kind of investigative reporter.

And what they did with this organization, which the Mercers poured millions of dollars into, was they aimed to kind of create the—drive the political narrative in the 2016 campaign. They created a book called Clinton Cash, which was a compendium of all the kinds of corruption allegations against the Clintons. And they aimed to get it into the mainstream media, where it would pretty much frame the picture of Hillary Clinton as a corrupt person who couldn’t be trusted. And their hope was that they would mainstream this information that they dug up. It was like an opposition research organization, sort of masked as a charity and nonprofit. And they took this book, Clinton Cash, gave it to The New York Times exclusively, early, and the Times then ran with a story out of it, that they said they corroborated. But they ran with it, nonetheless, on their front page, which just launched this whole narrative of Hillary Clinton as corrupt. And it just kept echoing and echoing through the media after that. So, it was a real home run for them. A year later, they made a movie version of it also, which they launched in Cannes.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re talking about Peter Schweizer and, as well, the Mercers. What about Cambridge Analytica, in addition to the Government Accountability Institute? And also, the Mercers’ obsession with the Clintons, the whole issue that you write about.

JANE MAYER: Well, this is something that—

AMY GOODMAN: They’re talking about they’re murderers.

JANE MAYER: I mean, really—I mean, one of the—one of the challenges of writing about the Mercers, for me, was to figure out—OK, so they’re big players. There are players in the Democratic Party who put in tons of money, too. They’re not the only people who put money into politics. But they’re maybe the most mysterious people who put money into politics. Like nobody really knew what do they believe, what’s driving them. And so, I was trying to figure that out.

And what I finally was able to do what was talk to partners and people they work with in business and people who’ve known them a long time, who paint this picture of them as having these really peculiar beliefs, and based on kind of strange far-right media. Among their beliefs are that—Bob Mercer has spoken to at least three people who I interviewed, about how he is convinced that the Clintons are murderers, literally, have murdered people. Now, you hear that on the fringes sometimes when you interview people who are ignorant, but these are people who are powerful, well educated and huge influences in the country. And Bob Mercer was convinced that the Clintons are murderers. OK, so he’s driven by this just hatred of the Clintons and, coming into 2016, is determined to try to stop Hillary Clinton, and looking for a vehicle who would do that, who eventually becomes Trump.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We continue our conversation with Jane Mayer, staff writer at The New Yorker. Her latest piece is headlined “The Reclusive Hedge-Fund Tycoon Behind the Trump Presidency: How Robert Mercer exploited America’s populist insurgency.” The piece looks at how the secretive billionaire reshaped the political landscape. But Robert Mercer is hardly a household name. He never talks to the press and rarely speaks at a public event.

AMY GOODMAN: But Robert Mercer did speak in 2014, when he accepted a lifetime achievement award from the Association of Computational Language. He told a story of working at New Mexico’s Kirtland Air Force Weapons Lab.

ROBERT MERCER: … its possession a program for computing these fields, but for whatever reason, they were not in possession of the programmer who had created it. It took hundreds of hours of CPU time to make a single run of this program, and my boss at the lab gave me the job of figuring out how it worked and making it run faster. The style of the original program was very unpleasant, so the first thing I did was rewrite the whole thing. And after a while, I had a new program that produced the same answers as the old one, but about a hundred times faster. And then a strange thing happened. Instead of running the old computations in 1/100th of the time, the powers that be at the lab ran computations that were a hundred times bigger. I took this as an indication that one of the most important goals of government-financed research is not so much to get answers as it is to consume the computer budget, which has left me ever since with a jaundiced view of government-financed research.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that is one of the few times Robert Mercer has spoken publicly. In fact, Jane Mayer, you talk about, at the heroes-and-villains ball after Donald Trump was elected, he said he had his longest conversation with Robert—with Robert Mercer, and he had uttered two words, he said. But—so he has this view of the government. He moves over to Renaissance Technologies in Setauket, Long Island, out near Stony Brook University. Talk about how you did learn more about his views—you mentioned the man earlier, David Magerman, one of the people he worked with at Renaissance, who broke with him; so often that’s how you can learn about people’s views within an organization, when you have a break, a major rift like this—and Magerman’s view of what the Mercers represent.

JANE MAYER: Well, I mean, it’s very unusual, what happened with this man, David Magerman. He is a senior employee at Renaissance Technologies, this wildly lucrative hedge fund. And he spoke out about Mercer’s views. I mean, the thing is, this hedge fund is very secretive. It has its own sort of secret sauce about how to make money. Nobody there talks. They’re all also getting so rich. There’s a lot to lose by alienating the people who run the firm. And so, it was very unusual that Magerman came forward.

But what happened was, he is involved in Jewish politics, Jewish causes in Philadelphia. And he became very concerned about the Mercers’ role in the campaign and the sort of the promotion of the “alt-right,” which has these anti-Semitic strains to it, and got into a conversation with Bob Mercer that devolved into an argument about politics. And at some point, Magerman said to his boss, Bob Mercer, you know, “You are using money that I helped earn for this firm to do these things. And if you’re harming America, you have to stop.” And he spoke to colleagues about it, and Mercer called him and said, “I understand you’re saying I am a white supremacist.” And Mercer said, “That’s ridiculous.” And Magerman said, “Well, I didn’t use those words exactly, but, you know, you’ve got to stop doing this.” Eventually, this fight got written up in The Wall Street Journal. Magerman spoke to The Wall Street Journal. And when that happened, when it went public, the firm suspended Magerman for 30 days from his job without pay, and—which God knows how much that would be.

And at that point, Magerman didn’t back down. He wrote an essay himself about how he saw things. And what he wrote is really very eloquent, I thought, which is that he says about his boss, Mercer, “He’s making an investment. He’s buying shares in this candidate, Trump. And now that Trump’s been elected, he owns a piece of him. He owns a share of the presidency.” And he said, you know, “Everybody’s got a right to express their own political views, but it’s a real worry when the government of the United States is being set up to reflect—is being peopled by Mercer’s people, who are running our government, and it feels more like an oligarchy than a democracy.” So, anyway, Magerman was one of the people who actually opened the—allowed one to get a glimpse of what it is that Mercer believes.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, I want to ask about someone who’s strongly influenced the views of Robert Mercer, Arthur Robinson, who is also the person that Mercer intervened on behalf of when he was running for Oregon’s governor. Now, in your piece, you talk about the influence that he’s had on Robert Mercer, especially on climate change and nuclear radiation. Robinson runs the Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine, which stores some 14,000 samples of human urine. Robinson has said he’s trying to find new ways of extending the human lifespan. In 2010, Mercers bankrolled Robinson’s run for a congressional seat in Oregon against Pete DeFazio. During the race, Arthur Robinson was interviewed by MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow.

RACHEL MADDOW: You’re well known for your belief that global warming is made up, that that is not true. That’s sort of the source of your national reputation, to the extent that you have one. Your opponent, Mr. DeFazio, is also—

ARTHUR ROBINSON: That’s not a belief. That’s a conclusion I reached as a physical scientist. I have a degree from Caltech.

RACHEL MADDOW: Right.

ARTHUR ROBINSON: Many other men who have degrees from Caltech have agreed with me on this.

RACHEL MADDOW: OK.

ARTHUR ROBINSON: We have—there are thousands of physical scientists in this country who, on the basis of scientific information alone, reject the idea of human-caused global warming.

RACHEL MADDOW: You have advocated that radioactive—

ARTHUR ROBINSON: You can go right ahead. You’ve already—you’ve already put a big pejorative statement before the statement. But go ahead. Ask anything you like.

RACHEL MADDOW: You have advocated that radioactive waste should be dissolved in water and, quote, “widely dispersed in the oceans.” Quote, “All we need to do with nuclear waste is dilute it to a low radiation level and sprinkle it over the ocean—or even over America after hormesis is better understood and verified with respect to more diseases.” Now, hormesis is your belief that low-level radiation is good for us to a certain extent? Is that right?

ARTHUR ROBINSON: The statements that you have just made are untrue.

RACHEL MADDOW: Wait. That was a—I was quoting you.

ARTHUR ROBINSON: What you have done is take tiny excerpts from a vast amount of writing I’ve done on this scientific subject. I have not advocated any of this. As a scientist, I’ve written—

RACHEL MADDOW: I—”All we need to”—did you not say this?

ARTHUR ROBINSON: —about these and many other possibilities.

RACHEL MADDOW: Wait, wait. Are you saying that I—

ARTHUR ROBINSON: You are—

RACHEL MADDOW: Are you saying that your own news—

ARTHUR ROBINSON: You are not telling the truth.

RACHEL MADDOW: Sir, are you saying that your—

ARTHUR ROBINSON: If you want to tell the truth, that’s fine. I’m not going to answer to your lie. That’s just more mud.

RACHEL MADDOW: I’m quoting from your own newsletter.

ARTHUR ROBINSON: This is a complicated scientific subject, which you are misrepresenting to your viewers.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So that’s Arthur Robinson speaking to Rachel Maddow, Arthur Robinson who has been an influence on Robert Mercer. And he bankrolled—sorry. He bankrolled this institute and has been pushed to be a science adviser to Trump, this man who believes that nuclear radiation is good for you. So could you say more about him, Robinson?

JANE MAYER: Well, he is an eccentric. He lives on a sheep farm in Oregon. And as he says, he’s a graduate of Caltech. But, you know, if you listen carefully to what he was saying to Rachel Maddow, he’s talking about how “I am a physical scientist, and thus can come to this conclusion about climate change.” He is not a climate scientist. And he put together a petition that was meant to undermine belief in global warming, that had the signatures, he claimed, of zillions of physical scientists. It actually had a lot of, apparently, false signatures. And these scientists, again, were not climate scientists.

The consensus, as I think most people who are fact-based and interested in reality—the consensus we know is that science, overwhelmingly, and particularly climate scientists, overwhelmingly, accept that man-made global warming is causing all kinds of problems and that they are an immediate danger to life on Earth, and it’s something that we need to address.

But you have a few of these sort of holdouts, and Arthur Robinson is one of them. And Mercer is another. And Mercer has helped fund this research by Arthur Robinson and then—and promote it. And the Mercers have talked about, as you mentioned, trying to make Arthur Robinson get chosen as the national science adviser. Trump, too, has taken this position, calling global warming a hoax. It’s a tiny minority view, even in this country. If you look at—The New York Times did a piece this week about belief in global warming. The population understands this isn’t—this isn’t true, this position that these people are taking. But because you’ve got huge money behind it, including Mercer’s, it’s being pushed as the policy of the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to talk to you about Steve Bannon, continue talking about, since he’s so important, White House chief strategist, who some call “President Bannon,” who—you write about his deep ties to the Mercers, who bankroll Breitbart News and Bannon’s film projects. Let’s turn to comments Bannon made in an interview last month at the CPAC, Conservative Political Action Conference.

STEPHEN BANNON: I think if you look at the lines of work, I kind of break it out into three verticals or three buckets. The first is kind of national security and sovereignty, and that’s your intelligence, the Defense Department, homeland security. The second line of work is what I refer to as economic nationalism. The third, broadly, line of work is what is deconstruction of the administrative state. … If you look at these Cabinet appointees, they were selected for a reason. And that is the deconstruction. The way the progressive left runs is that if they can’t get it passed, they’re just going to put it in some sort of regulation in an agency. That’s all going to be deconstructed. And I think that that’s why this regulatory thing is so important.

AMY GOODMAN: So that’s chief White House strategist Steve Bannon speaking last month. You mention in your piece, Jane, that Robert Mercer’s daughter Rebekah was part of Bannon’s entourage at CPAC. You also suggest Mercers aren’t ideologically aligned with Bannon on some issues. Can you talk about—more about the relationship between Bannon and the Mercers? You—even the possibility that Bannon doesn’t see himself that long in the White House?

JANE MAYER: I’m sorry, I didn’t hear. The possibility that Bannon doesn’t seem what?

AMY GOODMAN: See himself that long in the White House.

JANE MAYER: Ah. Well, from what I’ve been able to figure out, Bannon and Rebekah Mercer are quite close. They’re partners politically, in many ways. She’s the money in the team, and he is the kind of political vision. There are people who know the Mercers, who have worried that their kind of evolution into this tremendous political influence role is the work of Bannon and, to some—that he may have become kind of a Svengali to the whole family. But at any rate, they seem to be working closely together. In the past, they’ve talked a lot, quite frequently. Bannon is a social guest of the Mercer family. They have a tremendous yacht, 203 feet long, that costs $75 million. And he’s, you know, been described by The Wall Street Journal as kind of hanging out on it like a member of the family. And so, they are close. And they’re aligned on many things.

As you mentioned, there are areas of disagreement, particularly between Bob Mercer and Bannon, politically. Bob Mercer is stridently and extremely antigovernment, wants to just, you know, reduce it to a pinhead, according to David Magerman. And Bannon has been talking about an expensive, really expensive, infrastructure program in this country. And so, that would be a point of tension. That would be a government program that Bannon supports and that this family does not. But they are aligned on this idea of deconstructing the administrative state, which sounds like gobbledygook. But what is it really? They’re talking about completely gutting all kinds of government programs and regulations that have to do with things like the environment, that they’ve—just completely undoing the EPA from the inside by putting someone like Scott Pruitt in charge of it, who, basically, doesn’t believe in its mission.

AMY GOODMAN: Who has sued it 14 times—

JANE MAYER: Bannon—right.

AMY GOODMAN: —as Oklahoma attorney general.

JANE MAYER: Right. And so, you know, Bannon—the language is the language of populism. But the enemy, in his view, is government. And so, if you substitute the word “government” for “elites,” when he’s talking about taking on the elites, you end up pretty much in the same place where the Kochs have been all this time, the Koch brothers, who actually worked closely with the Mercers for a few years. They’re undoing the—sort of the government as we know it, which has, you know, the protections for people, for workers, for the environment, for the poor, for the disabled. That’s where—that’s where they’re heading with this.

AMY GOODMAN: One of the companies heavily funded by Robert Mercer is Cambridge Analytica, which claims it has psychological profiles of over 200 million American voters. The firm was hired by the Trump campaign to help it target its message to potential voters. Steve Bannon even served on the company’s board. This is Cambridge Analytica’s CEO, Alexander Nix, speaking earlier this year.

ALEXANDER NIX: We started to look at issue models, predicting which issues, social and political, appeal to which members of the target audience, which voters. We actually assigned different issues to every adult in the entire United States. We could then take these models and put them into a matrix, a little bit like the dental health example, where we can categorize people or segment them according to how they’re likely to behave. Core Trump supporters, top right, may be more susceptible to a donation solicitation. Get out the vote: people who are going to vote Republican, but they need persuading to do so. Persuasion audiences: people who need shifting a little bit from the center towards the right. Once we’ve identified a segment, we can then subsegment them by the issues that are most relevant to them, and then start to target them with specific messages.

AMY GOODMAN: Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix. So, Cambridge Analytica has—claims to have psychological profiles of over 200 million American voters. Jane Mayer, tell us its significance. Steve Bannon was on its board, funded by the Mercers.

JANE MAYER: Well, again, this is part of—if you look at the history, what happened was, after 2012, when Obama was re-elected, despite the fact that the Mercers had put millions of dollars into trying to defeat him, they were upset, and they wanted to try to get better political tools with more traction. So they put money into Breitbart. They put money into the Government Accountability Institute. And the third prong was Cambridge Analytica.

It was—at that point, they concluded, and so did many others, that the Republican Party’s data analytics for running campaigns were lagging behind those that the Democrats had. The Democrats—Obama had a famously good sort of computer operation and data team. And so, they tried to—they decided, “We’ll run our own.” They bought a company. They basically invested heavily in building an—it’s an offshoot of an existing English company called Strategic Communication Laboratories. And the British company had been involved in psychological warfare operations for militaries and international elections and kind of some pretty interesting and sneaky-seeming things, which raised a lot of eyebrows when its offshoot was purchased, basically, created by this one hedge-fund family.

You know, when I looked into this, it seemed that there was less than meets the eye, in many ways, so far. Alexander Nix, who is running Cambridge Analytica, is a great salesman, and he’s got this pitch that makes it sound like something from, you know, the movie The Matrix or something, that they’re going to be conducting psychological warfare with this propaganda machine in this country. The truth is, during the Trump campaign, they never used any of their so-called secret psychometric methods. They simply performed like any other kind of data analytics company. And the stuff they did was no different from what the Democrats do and other campaigns do. You know, maybe at some point they’ll have some superpowers that have yet to be revealed, but they aren’t there yet.

AMY GOODMAN: Jane, before we wrap up, we want to go to the Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Judge Neil Gorsuch, really interesting dialogue between Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse questioning Gorsuch on the $10 million dark money campaign supporting his nomination.

SEN. SHELDON WHITEHOUSE: If a question were to come up regarding recusal on the court, how would we know that the partiality question in a recusal matter had been adequately addressed if we did not know who was spending all of this money to get you confirmed? Hypothetically, it could be one individual. Hypothetically, it could be your friend, Mr. Anschutz. We don’t know, because it’s dark money. Is it any cause of concern to you that your nomination is the focus of a $10 million political spending effort and we don’t know who’s behind it?

JUDGE NEIL GORSUCH: Senator, there’s a lot about the confirmation process today that I regret.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Judge Neil Gorsuch being questioned by Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse. Jane Mayer, in this last 30 seconds that we have, can you comment on this?

JANE MAYER: Well, yeah. I mean, the thing about dark money is, often the person who it’s benefiting knows; it’s just the public that’s not allowed to know. And there’s tons of money behind the Gorsuch nomination, and he probably knows who he owes the favor to.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain a little further the term “dark money.”

JANE MAYER: Well, there are these organizations, 501(c)(4) groups, that are set up, where the donors’ hands are not seen. They can spend money on advertising, and the public doesn’t know who they are. They’re nonprofit groups such as the Judicial Crisis Network. And I’ve looked at that one. And, you know, you, as a reporter, and me, as standing in for the public, cannot trace the money. Yet it’s playing an active role in American politics.

Media Options