Guests

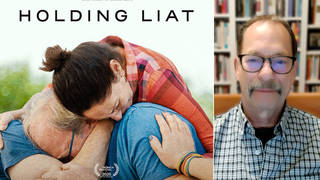

- Seva Gunitskyassociate professor of political science at the University of Toronto. He is the author of Aftershocks: Great Powers and Domestic Reforms in the Twentieth Century.

President Trump on Wednesday said he never would have nominated Jeff Sessions to be attorney general had he known Sessions was going to recuse himself from a Justice Department investigation into alleged ties between Russia and Trump associates. One Russia expert says the smoking gun indicating a quid pro quo between Russian money and Trump may lie with a little-known case that was abruptly settled involving a holding company linked to the Russian elite. Prevezon’s lawyer is Natalia Veselnitskaya—the same Russian woman who initiated the now-infamous meeting with Donald Trump Jr. last June. We speak with author and Russia expert Seva Gunitsky, associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: President Trump said Wednesday he never would have nominated Jeff Sessions to be attorney general if he had known Sessions was going to recuse himself from a Justice Department investigation into alleged ties between Russia and Trump’s associates. The president made the remarks during a wide-ranging interview with The New York Times.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: [Jeff Sessions] takes the job, gets into the job, recuses himself. I then have—which—which, frankly, I think, is very unfair to the president. How do you take a job and then recuse yourself? If he would have recused himself before the job, I would have said, “Thanks, Jeff, but I can’t—you know, I’m not going to take you.” It’s extremely unfair—and that’s a mild word—to the president.

AMY GOODMAN: President Trump also left open the possibility that he could order the Justice Department to fire special counsel Robert Mueller, who’s been assigned to investigate Russia’s role in the 2016 election. This is Trump, again, speaking in the Oval Office with New York Times reporters.

MICHAEL SCHMIDT: If Mueller goes looking at your finances or your family’s finances unrelated to Russia, is that a red line?

MAGGIE HABERMAN: Would that be a breach of what his actual charge is?

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: I would say yeah. Yeah, I would say yes. By the way, I would say, I don’t—I don’t—I mean, it’s possible that there’s a condo or something. So, you know, I sell a lot of condo units. And if somebody—if somebody from Russia buys a condo, who knows? I don’t make money from Russia. In fact, I put out a letter saying that I don’t make—from one of the most highly respected law firms and accounting firms. I don’t have buildings in Russia. They’ve said I own buildings in Russia. I don’t. They said I made money from Russia. I don’t. It’s not my thing. I don’t—I don’t do that. Over the years, I’ve looked at maybe doing a deal in Russia, but I never did one, you know, other than that I held a Miss Universe pageant there, eight, nine years ago.

AMY GOODMAN: To talk more about Trump’s ties to Russia, we’re joined now by Seva Gunitsky. He is an associate professor of political science at University of Toronto, author of Aftershocks: Great Powers and Domestic Reforms in the Twentieth Century. He recently wrote a piece headlined “Trump and the Russian Money Trail.”

OK, Seva, please lay out what you found.

SEVA GUNITSKY: Well, sure. I think, in the Russia story, Putin has loomed very large. And he’s sort of a perfect antagonist for this. But if you want to get at the roots of the collusion, you have to look at where Trump’s links with Russia actually begin. And they don’t begin with Putin. They certainly don’t begin with the 2016 campaign. They begin with long-standing financial linkages that Trump has, going back to the ’90s, even earlier, to Russian oligarchs who have been pouring money into his real estate and into his casino business for quite some time.

AMY GOODMAN: Lay out exactly. And if you can talk about how perhaps this relates to who was in the room with Donald Trump Jr., Donald Trump’s oldest son, and Kushner, his son-in-law, as well as Paul Manafort, his campaign manager at the time, when they had this meeting that they’ll all have to be speaking before a Senate committee about next week?

SEVA GUNITSKY: Sure. And I want to say, this is not just small change from Russia, despite what Donald Trump says. This has been hundreds of millions of dollars. Donald Trump’s son, Don Jr., said—almost a decade ago, he said that “Russians make up a disproportionate number of our investors. We have money pouring in from Russia.” That’s a direct quote. So, he has been a sort of perfect vehicle for Russian investments.

And if you look at the people who were in the room in that now-infamous meeting last June, then it’s clear that there are many linkages to Russian money. We have people like the business partner of Aras Agalarov, a Russian oligarch that Trump has been doing business with for years. We have people like Natalia Veselnitskaya, who is a lawyer for a company called Prevezon, which was accused of laundering hundreds of millions of dollars through New York City real estate. So, it’s not a surprise that these names keep coming up, because this is definitely something that has linked Trump to Russia for a long, long time.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And could you talk about, Seva, the 2012 Magnitsky Act and what role it plays here?

SEVA GUNITSKY: Sure. So, the 2012 Magnitsky Act was a result of a Russian lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, who was investigating a company in Russia that was linked to some illegal activities by Russian oligarchs. And when he found out what happened, he was put in jail, and he was murdered in jail. So, in 2012, the Obama administration, as a response, put in an act, the Magnitsky Act, that essentially prevented wealthy Russians from doing business in the U.S. And the Russian oligarchs despise this act. They really would like to see it canceled.

And the lawyer who met with Don Jr., Natalia Veselnitskaya, she had been lobbying against the Magnitsky Act for years. I’ve looked through her Russian-language social media postings, and she just rails against it for a long time. So, with things like the Prevezon case, she was very happy to see the case settled just a few months ago. And here, the timing becomes very odd, because she was a lawyer for Prevezon. She meets with Donald Trump in June. We don’t know exactly what she was asking for, but months after Donald Trump takes office, the Prevezon case is settled. It was settled in May, very suddenly and in a very strange way. The government was all set to prosecute. They had been ready to prosecute; for years, they’d been charging the case. And all of a sudden, they settled it, for a fraction of the money that they were looking for, no disclosure, no trial. So Veselnitskaya was ecstatic about this. On her—on her social media, she said this is—”This case was settled on Russian terms.” That’s a direct quote. And she promised more to come.

So, if you’re looking for any sort of quid pro quo between Russian money and Trump, this might be a smoking gun, because here we have a case where questions now arise whether the Department of Justice, under Jeff Sessions, put pressure on a district attorney’s office—Preet Bharara, namely, who was in charge of the case—to settle the case quickly. Now, Bharara was fired in March. And several weeks after he was fired, the case was quickly settled. So, it’s a nice set of coincidences. And maybe at this point it’s hard to say that it’s just coincidences. It’s more of a pattern of deep, deep ties between financial interests in Russia and the Trump campaign.

AMY GOODMAN: Seva Gunitsky, what about Ike Kaveladze? He is the eighth person identified as being a part of that meeting, who is the Soviet-born U.S. citizen.

SEVA GUNITSKY: I don’t know if you can hear me, but the show just cut out.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m asking you about Ike Kaveladze.

SEVA GUNITSKY: I hope it’s not Russian hacking, but I can’t hear anything.

AMY GOODMAN: Oh, can you hear me now? Can you hear me now? OK. Sorry. So, we’re talking to professor Seva Gunitsky, who is associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto. We may be able to go back to him. But right now, we’re going to turn—

SEVA GUNITSKY: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you hear me now, Seva?

SEVA GUNITSKY: Yes, I can hear. That was very strange.

AMY GOODMAN: OK, very quickly, if you could talk about the eighth person in the room, who has been identified, the person who represented—Ike Kaveladze, the Soviet-born U.S. citizen, who attended as a representative of the father-and-son Russian developers?

SEVA GUNITSKY: That’s right. So, Kaveladze, initially, was assumed to be a translator. But I’ve seen his English-language writing. He is not that good at English. He definitely was not there in his capacity as a translator. I think what’s more likely is that Kaveladze, keep in mind, was business partner—is business partners with Agalarov, who is Trump’s friend and a Russian oligarch. He, Kaveladze, was a middleman, since the early ’90s, between Russian oligarchs and the American financial system. In 2000, he was implicated in the Bank of New York scandal, which also had massive ties to Russian money laundering. So I think all of those factors suggest that, again, financial ties—whatever was discussed at the meeting, financial ties were very much at the core of it.

Media Options