Guests

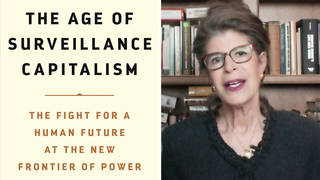

- Siva Vaidhyanathanauthor of Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy. He is a professor of media studies and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship at the University of Virginia. His previous books include The Googlization of Everything.

“Black Elevation.” “Mindful Being.” “Resisters.” “Aztlan Warriors.” Those are the names of some of the accounts removed from Facebook and Instagram Tuesday after Facebook uncovered a plot to covertly influence the midterm elections. The tech giant said 32 fake accounts and Facebook pages were involved in “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” This announcement comes just days after the company suffered the biggest loss in stock market history: about $119 billion in a single day. This is just the latest in a string of controversies surrounding Facebook’s unprecedented influence on democracy in the United States and around the world, from its pivotal role in an explosion of hate speech inciting violence against Rohingya Muslims in Burma to its use by leaders such as Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte in suppressing dissent. Facebook has 2.2 billion users worldwide, and that number is growing. We speak with Siva Vaidhyanathan, author of “Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy.” He is a professor of media studies and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship at the University of Virginia.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: “Black Elevation.” “Mindful Being.” “Resisters.” “Aztlan Warriors.” Those are the names of some of the accounts removed from Facebook and Instagram Tuesday, after Facebook uncovered a plot to covertly influence the midterm elections. The tech giant said it uncovered 32 fake accounts and Facebook pages that were involved in what it described as “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” The accounts had a total of 290,000 followers, that had—that created 30 events since April of 2017. One of the accounts had created a Facebook event to promote the protest against the upcoming Unite the Right rally in Washington, D.C. Protest organizers say the fake account is not behind the event. Facebook says it does not have enough technical evidence to state who was behind the fake pages, but said the accounts engaged in some similar activity to pages tied to Russia before the 2016 election. Facebook’s announcement comes just days after the company suffered the biggest loss in stock market history, losing about $119 billion—that’s right, billion dollars—in a single day.

AMY GOODMAN: Facebook has been at the center of a number of controversies in the United States and abroad. Earlier this year, Facebook removed more than 270 accounts it determined to be created by the Russia-controlled Internet Research Agency. Facebook made that move in early April, just days before founder and CEO Mark Zuckeberg was question on Capitol Hill about how the voter-profiling company Cambridge Analytica harvested data from more than 87 million Facebook users without their permission in efforts to sway voters to support President Donald Trump. Zuckerberg repeatedly apologized for his company’s actions then.

MARK ZUCKERBERG: We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake. And it was my mistake, and I’m sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I’m responsible for what happens here.

AMY GOODMAN: Today we spend the hour with a leading critic of Facebook, Siva Vaidhyanathan, author of Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy. He’s professor of media studies and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship at the University of Virginia. We’re speaking to him in Charlottesville.

Professor, welcome to Democracy Now!

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Oh, thanks. It’s good to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let’s begin with this latest news. There are hearings today that the Senate Intelligence Committee is holding, and yesterday Facebook removed these—well, a bunch of pages, saying they don’t know if it’s Russian trolls, but they think they are inauthentic. Talk about these pages, what they mean, what research is being done and your concerns.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah. Look, Facebook was unconcerned, for nearly a decade, that various groups, either state-sponsored or sponsored by some, you know, troublemaking group, were popping up around Facebook, not just in the United States, not just in reference to one election or another, but around the world, in a concerted effort, or in some ways a distributed effort, to undermine democracy and civil society. This has been going on almost as long as Facebook has allowed pages to pop up—right?—interest group pages to pop up. And Facebook got caught off guard, bizarrely, after the 2016 election, even though there were people within Facebook who were raising the alarm—right?—that there were these pages, these accounts, that were distributing nonsense, that were posing as Black Lives Matter pages. There were others that were posing as Texas independence pages. There were some supporting radical-right positions and others supporting radical-left positions. And, you know, they were planning events. So, all of this came out after the 2016 election. It should have come out before. And Facebook has been scrambling ever since.

So, what we’ve seen since the 2016 election in the United States is, every time there is a major election around the world, Facebook will put all hands on that election and try to make sure that it can claim that it is cleaning up its act in preparation for that election. So we saw that in 2017 with the elections in Germany and in the Netherlands and in France. We saw that with the referendum on abortion that was held in Ireland earlier this year. In all of these cases, you know, Facebook has made sure to crow about all that it has done to clean up the pollution that might distract people or disrupt the political process, the democratic process.

But, you know, it hasn’t done much in other places in the country. It did almost nothing in Mexico before its election. It has so far come up with no strategy for dealing with the much larger mess in India, the world’s largest democracy. Facebook was instrumental in the election of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines in 2016. It was instrumental in the Brexit referendum in 2016. In all of these cases, forces, often from other countries, interfered in the democratic process, distributed propaganda, distributed misinformation, created chaos, often funneled campaign support outside of normal channels, and it’s largely because Facebook is so easy to hijack.

What we see just this week, as Facebook makes these announcements, is that they’ve managed to identify a handful of sites that, you know, a few hundred thousand people have interacted with. We don’t know if this is 5 percent, 10 percent, 50 percent or 100 percent of the disruptive element going on before our off-year elections coming up in November.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Professor, one of the points that you make in your book is that so much attention has been focused on the work of Cambridge Analytica, but that you believe that there’s a much deeper structural problem with Facebook than just one company being able to access personal data and then use it for nefarious political ends. Could you talk about the structural issues that you see? And also, you mentioned the Philippines. Most people have not heard much about how Duterte was helped to win his election by Facebook. If you could give an example of how structurally it might have worked in the Philippines?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah. Look, Cambridge Analytica was a great story, right? It finally brought to public attention the fact that for more than five years Facebook had encouraged application developers to get maximal access to Facebook data, to personal data and activity, not just from the people who volunteered to be watched by these app developers, but all of their friends—right?—which nobody really understood except Facebook itself and the application developers. So, thousands of application developers got almost full access to millions of Facebook users for five years. This was basic Facebook policy. This line was lost in the storm over Cambridge Analytica.

So, Cambridge Analytica was run by Bond villains, right? They look evil. They work for evil people, like Kenyatta in Kenya. You know, Steve Bannon helped run the company for a while. It’s paid for by Robert Mercer, you know, one of the more evil hedge fund managers in the United States. You know, it had worked for Cruz, for Ted Cruz’s campaign, and then for the Brexit campaign and also for Donald Trump’s campaign in 2016. So it’s really easy to look at Cambridge Analytica and think of it as this dramatic story, this one-off. But the fact is, Cambridge Analytica is kind of a joke. It didn’t actually accomplish anything. It pushed this weird psychometric model for voter behavior prediction, which no one believes works.

And the fact is, the Trump campaign, the Ted Cruz campaign, and, before that, the Duterte campaign in the Philippines, the Modi campaign in India, they all used Facebook itself to target voters, either to persuade them to vote or dissuade them from voting. Right? This was the basic campaign, because the Facebook advertising platform allows you to target people quite precisely, in groups as small as 20. You can base it on ethnicity and on gender, on interest, on education level, on ZIP code or other location markers. You can base it on people who are interested in certain hobbies, who read certain kinds of books, who have certain professional backgrounds. You can slice and dice an audience so precisely. It’s the reason that Facebook makes as much money as it does, because if you’re selling shoes, you would be a fool not to buy an ad on Facebook, right? And that’s drawing all of this money away from commercially based media and journalism. At the same time, it’s enriching Facebook. But political actors have figured out how to use this quite deftly.

So, when Modi ran in 2014, when Duterte ran in 2016, in both cases, Facebook had staff helping them work their system more effectively. Facebook also boasted about the fact that both Modi and Duterte were Facebook savvy—right?—the most connected candidates ever. In fact, Narendra Modi has more Facebook friends and followers than any other political figure in the world. He is the master of Facebook. It’s not a coincidence that Narendra Modi and Rodrigo Duterte are dangerous nationalist leaders who have either advocated directly for violence against people, their own people, or have sat back and folded their arms as pogroms happened against Muslims in their country.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: You mentioned Narendra Modi. I want to turn to a meeting between Mark Zuckerberg and the Indian prime minister at the Facebook headquarters in California in 2015.

MARK ZUCKERBERG: You were one of the early adopters of the internet and social media and Facebook. And did you, at that point, think that social media and the internet would become an important tool for governing and citizen engagement in foreign policy?

PRIME MINISTER NARENDRA MODI: [translated] When I took to social media, even I actually didn’t know that I would become a chief minister at some point, I would become a prime minister at some point, so I never, ever did think that social media would actually be useful for governance. When I took up and I got onto social media, it was basically because I was curious about technology. And I saw that I had been trying to understand the world through books, but I think it’s a part of human nature that, instead of going onto textbooks, if you have a guide, it’s far easier. And, in fact, if, instead of a guide, somebody can give you pretty sure suggestions of what to do, it’s even better.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That was Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi talking with Mark Zuckerberg at Facebook headquarters in California in 2015. Professor, could you talk about this whole—the impact that Modi has had on the internet? He has what? I mean, 43 million Facebook followers?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Right, and that doesn’t include WhatsApp, right? WhatsApp is the most popular messaging service in India. It’s also owned by Facebook, right? And it’s tremendously important not just in personal communication, but in harnessing mobs for mob violence, mostly against Muslims, but often against Christians and often against Hindus who happen to marry or date Muslims. You know, this sort of vigilante mob violence is breaking out all over India. It’s breaking out in Sri Lanka. We’ve seen the Rohingya massacres and expulsion in Myanmar, in Burma, often fueled—in fact, directly fueled by propaganda spread on Facebook and WhatsApp.

And Modi has taken full advantage of this. Right? He and his people mastered this technique early on. It’s a three-part strategy, which I call the authoritarian playbook. What they do is they use Facebook and WhatsApp to distribute propaganda about themselves, flooding out all other discussion about what’s going on in politics and government. Secondly, they use the same sort of propaganda machines, very accurately targeted, to undermine their opponents and critics publicly. And then, thirdly, they use WhatsApp and Facebook to generate harassment, the sort of harassment that can put any nongovernment organization, human rights organization, journalist, scholar or political party off its game, because you’re constantly being accused of pedophilia, you’re being accused of rape, or you’re being threatened with rape, threatened with kidnapping, threatened with murder, which makes it impossible to actually perform publicly in a democratic space. This is exactly what Modi mastered in his campaign in 2014, and, in fact, a bit before. And that same playbook was picked up by Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and it’s being used all over the world by authoritarian and nationalist leaders, to greater or lesser degrees.

So, in the United States, when Trump’s campaign used Facebook, almost as effectively, to precisely target certain voters in certain states, like Michigan, like Wisconsin, like Pennsylvania, like Florida, and either turn them off from voting or turn them on to voting for Donald Trump, when they might not have been otherwise motivated, by choosing very targeted, specific issues, again, to either turn people on or off from voting, that was a sort of soft, light version of Narendra’s authoritarian playbook. We did not see, and we’ve not seen yet, and hopefully we will not see, the same level of coordinated harassment from the Republican Party. At least we haven’t seen it yet. So, you know, what we are seeing, of course, in a distributed way, anybody who, especially women, who are involved in the public sphere are constantly being assaulted with these messages of all sorts of threats, both publicly and privately. So, you know, the culture of our democracy and the cultures of democracies around the world are directly threatened by these practices, that are not only enabled by Facebook, they’re actually accelerated by Facebook.

AMY GOODMAN: We are going to break, then come back to this discussion and talk about a number of issues, including whether you’re concerned about this massive monopoly determining the content we read and see. Siva Vaidhyanathan is the author of Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy, professor of media studies and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship at the University of Virginia. His previous books include The Googlization of Everything. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Every Breath You Take” by The Police. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. We’re spending the hour with professor Siva Vaidhyanathan, who is author of Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy. He’s speaking to us from Charlottesville, from the University of Virginia, professor of media studies and head of the Center for Media and Citizenship at UVA. Your book, Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy.

I want to go back to the beginning of this interview, where we talked about Facebook taking down more than 30 pages, saying that they are not authentic. We immediately got responses from all over saying the protest against the Unite the Right rally in Washington, D.C., in August, around the anniversary of the attacks at your university, University of Virginia, are real. These protests against Unite the Right are real. So, this goes to a very important issue, Professor, that you now have Facebook, this corporation, deciding what we see and what we don’t see. It’s almost as if they run the telephone company and they’re listening to what we say and deciding what to edit, even if some of the stuff is absolutely heinous that people are talking to each other about—the idea of this multinational corporation becoming the publisher and seen as that and determining what gets out. So, yes, there’s a protest against Unite the Right. That is very real. They’ve taken down one page, that might not have been real, organizing the protest against Unite the Right. And the Unite the Right rally is supposed to be happening. What, for example, would happen if there was a protest against Facebook, Siva?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah, you can’t use Facebook to protest against Facebook, by the way. You can’t even use Facebook to advertise a book about Facebook, for actually one—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Well, they will not allow a group or a page or an advertisement to contain the word “Facebook.” And it’s not just to insulate themselves from criticism. That is a nice bonus for them. But it’s really because they don’t want any sort of implication that the company itself is endorsing any group or page or product. So, the use of the word—look, the only way Facebook operates is algorithmically, right? It has machines make very blunt decisions. So the very presence of the word “Facebook” will knock a group down or knock a page down. And so you can’t use Facebook to criticize Facebook, not very effectively.

AMY GOODMAN: So what about your book, which has the word “Facebook” in it?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Right. I can’t—I can’t buy ads on Facebook about it. But that’s OK. I think I’ll do OK.

However, OK, so, thinking about this notion of the extent to which Facebook governs our structures, our sense of awareness, our public sphere—right?—so Facebook is a place where, a source from which, more than half of Americans regularly get news. That should be of some concern, because, as you said, Facebook’s algorithms decide what we see and what we don’t see. And it reflects—the algorithms reflect what we have already told Facebook we care about. So, if we have engaged with the Democracy Now! page for many years in lots of ways and put comments under items on that page, there is a very good chance that a lot of Democracy Now! content will show up in a news feed. If you deal with Breitbart just as effectively or just as often, you’re going to get a lot of Breitbart content and a lot less Democracy Now! content. And that’s—from Facebook’s point of view, it makes sense, right? They want to give you more of what you want. They want to keep you hooked on Facebook. They want to amplify their effect on your life. And, you know, like a casino—right?—they want—they’re constantly trying to convince you that you’ll feel a little bit better if you engage with Facebook. And being reinforced in your beliefs is a lovely feeling, right? So, what happens there is your field of vision narrows over time. And the same thing happens with Google, the more you interact with that. This has a number of effects, but it definitely makes us less able to interact with those who differ from us, in a humane way, in a respectful way. It’s not the only contributor to this phenomenon, but it certainly doesn’t help. And the more that we perform our politics and the more we try to learn about the world through Facebook, the more that we are denying ourselves a broad lens, a broad vision. And that’s a shame.

But in addition, Facebook has the ability to get hijacked, because what it promotes mostly are items that generate strong emotions. What generates strong emotions? Well, content that is cute or lovely, like puppies and baby goats, but also content that is extreme, content that is angry, content that is hateful, content that feeds conspiracy theories. And this hateful, angry conspiracy theory collection doesn’t just spread because people like it. In fact, it, more often than not, spreads because people have problems with it. If I were to post some wacky conspiracy theory on my Facebook page today, nine out of 10 of the comments that would follow it would be friends of mine arguing against me, telling me how stupid I was for posting this. The very act of commenting on that post amplifies its reach, puts it on more people’s news feeds, makes it last longer, sit higher. Right? So the very act of arguing against the crazy amplifies the crazy. It’s one of the reasons that Facebook is a terrible place to deliberate about the world. It’s a really effective place if you want to motivate people toward all sorts of ends, like getting out to a rally. But it’s terrible if you actually want to think and discuss and deliberate about the problems in the world. And what the world needs now more than anything are more opportunities to deliberate calmly and effectively and with real information. And Facebook is working completely against that goal.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I wanted to ask you about the political economy underlying not social media per se, because, I mean, I think your book is—it has to be, in my mind, one of the most—the most important book, nonfiction book, of this year, if not of the last decade—

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Oh, thank you.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —because so many people use Facebook—2.2 billion people around the world now use it. And so it’s extremely important, for the users especially, to look at the mechanics of this monster that’s been created over the last decade or so. But one of the things that it seemed to me, to some degree, you didn’t address is the issue of the political economy underlying all of this social media. I think, for instance, of Julian Assange’s book, Cypherpunks, where he talks about the dangers of the internet, and he also goes into this issue of the difference between the platonic view of how the internet and social media work and the actual physical underpinnings—the cable systems, the satellites—the physical structures that make the social media possible, and how governments and corporations have, in effect, hijacked this privatization of the internet, of this communications medium. I’m wondering if you could address how government policy made the development of a Google or a Facebook possible.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Look, back in the late 1990s, we were sold a vision, a dream of an internet that was a separate phenomenon from our real world. We called it cyberspace. We used spatial metaphors for it. We had people like John Perry Barlow rhapsodizing about the fact that rules don’t apply and this space will be exempt from both the prejudices of regular human beings and the limitations of the state, that the state puts on us. That never really existed. It was always a dream. The internet was commercialized and structured almost immediately, not extremely at the beginning. And if you remember, in the early part of the 21st century, we did have this proliferation of voices, largely through blogs, that was the dominant form of expression for amateurs, for voices yet to be heard, for emerging voices, for minority voices, to generate audience and put their message out. And it also meant that in those rather innocent days, you could discover new voices from other voices—right?—through links and recommendations. But nothing was structured by algorithms, and nothing was fueled by advertising, at least not effectively, right? In those days, web advertising didn’t make anybody any money.

Well, Google changed that, and, quickly after that, Facebook changed that. Right? So, by around 2002, Google figured out how to target ads quite effectively based on the search terms that you had used. By about 2007, Facebook was starting to build ads into its platform, as well. And because it had so much more rich information on our interests and our connections and our habits, and even, once we put Facebook on our mobile phones, our location—it could trace us to whatever store we went into, whatever church or synagogue or mosque we went into; it could know everything about us—at that point, targeting ads became incredibly efficient and effective. That’s what drove the massive revenues for both Facebook and Google. That’s why Facebook and Google have all the advertising money these days, right? It’s why the traditional public sphere is so impoverished, why it’s so hard to pay reporters a living wage these days, because Facebook and Google is taking all that money—are taking all that money, because they developed something better than the display ad of a newspaper or magazine, frankly. But there was just no holding back on that. As a result, once Facebook goes big, once Twitter emerges around 2009, you start seeing—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But if I can interrupt you for a second on this point—

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —their ability to monetize our use.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Also, doesn’t it depend on government’s refusal to defend privacy rights, policy decisions that our leaders make—

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah, absolutely.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —that people’s privacy rights no longer matter?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Absolutely. Now, that varies across the globe, of course. In Europe, there are much stronger data protection laws. There always have been, but, as of May 2018, they’re much better codified and clearer. And so Facebook and Google have a harder time targeting people effectively in Europe than they do in the rest of the world, especially in North America. We have no real protections of our data. We have no rights to our own data in the United States, effectively. We are merely rats in a cage or cows in a pasture to Facebook and Google in the United States and in Canada, in Australia, in South Africa, in Brazil and India and most of the world. It really—Europe is the exception in this case. And fairly soon, the U.K. won’t even be part of that exception. So, it’s a really sad state of affairs.

Many of us, for more than a decade, have been calling for strong data protection, so that we would be informed as to what our data is being used for, who gets our data. And we would be informed and asked for explicit permission every time a company shares our data or gives our data or sells our data to another party. It’s been impossible to get those legislative proposals through legislatures, largely because the lobbies against data protection go beyond Facebook and Google. They include Verizon and AT&T and T-Mobile. They include Comcast. Right? Some of the most powerful companies in the world are wedded to this massive surveillance capitalism model that has enriched Facebook and Google. They see—right? Comcast sees its only hope, to be in the advertising business, to compete against Facebook and Google, to do exactly what Facebook and Google have been doing. So Comcast very much wants to know as much about you as Facebook does. It’s not there yet, but it hopes to get there. So that’s one of the reasons we’re up against formidable political foes when we try to argue for basic human dignity and the ability for people to have some say over how they’re being used and abused.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break, and when we come back, there is a Senate intelligence hearing today on Facebook, and the question that we want to put to you is what do you think should be asked, and what should the government be doing to rein in these corporations. Siva Vaidhyanathan is the author of Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy, professor of media studies and director of the Center for Media and Citizenship at the University of Virginia, speaking to us from Charlottesville. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Watching Me” by Jill Scott, here on Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González, as we continue this hour with Siva Vaidhyanathan, who is the author of the book Antisocial Media. I want to turn to your recent Guardian piece—you wrote it after the single largest Wall Street drop in history, and that was Facebook—the piece you wrote titled “The panic over Facebook’s stock is absurd. It’s simply too big to fail.” At the end of the piece, you concluded, “we can’t depend on market forces to rein in Facebook’s destructive power. Investors won’t save us. Facebook itself won’t save us. Only a global political movement aimed at breaking up that company and limiting what it can do with our behavioral data can curb Facebook. Don’t let a one-day drop as part of a remarkable six-year surge in stock value distract you from that difficult truth.” Siva, why don’t you take it from there? On this day of the Senate intelligence hearing, talk about what you see as Facebook’s threat to democracy. What should be done about it? And what does it mean to say break it up?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah, so, almost all of the maladies that Facebook either causes or amplifies are the result of scale. Facebook got so big so fast, it became impossible to govern internally and really difficult to regulate externally. Right? So, consider that 2.2 billion people use Facebook. That was as of February 2018. By January 2019, that could be 2.4 billion people. The growth is actually extremely strong and fast, mostly in places in the world where one would expect and actually want to see growth—Brazil, Mexico, Nigeria, Kenya, India, the Philippines, Indonesia, etc.—right?—those—Pakistan. Countries where there are a lot of young people, there are a lot of people getting Facebook accounts every month. Right now, there are 220 million Americans who regularly use Facebook. That’s pretty flat. But there are 250 million people in India who regularly use Facebook, so more than in the United States. And that’s only a quarter of the population of India. So, not only is the future of Facebook in India, the present of Facebook is in India. So let’s keep that in mind. This is a global phenomenon. The United States matters less and less every day.

Yet the United States Congress has inordinate power over Facebook. The fact that its headquarters is here, for one thing. The fact that the major stock markets of the world pay strong attention to what goes on in our country, right? So we have the ability, if we cared to, to break up Facebook. We would have to revive an older vision of antitrust, one that takes the overall health of the body politic seriously, not just the price to consumers seriously. But we could and should break up Facebook. We never should have—excuse me—allowed Facebook to purchase WhatsApp. We should never have allowed Facebook to purchase Instagram. Those are two of the potential competitors to Facebook. If those two companies existed separately from Facebook and the data were not shared among the user files with Facebook, there might be a chance that market forces could curb the excesses of Facebook. That didn’t happen. We really should sever those parts. We should also sever the virtual reality project of Facebook, which is called Oculus Rift. Virtual reality has the potential to work its way into all sorts of areas of life, from pilot training to surgeon training to pornography. In all of these ways—to shopping—right?—to tourism. In all of these ways, we should be very concerned that Facebook itself is likely to control all of the data about one of the more successful and leading virtual reality companies in the world. That’s a problem. Again, we should spin that off. But we should also limit what Facebook can do with its data. We should have strong data protection laws in this country, in Canada, in Australia, in Brazil, in India, to allow users to know when their data is being used and misused and sold.

Those are necessary but, I’m afraid, insufficient legislative and regulatory interventions. Ultimately, we are going to have to put Facebook in its place and in a box. We are going to have to recognize, first of all, that Facebook brings real value to people around the world. Right? There are not 2.2 billion fools using Facebook. There are 2.2 billion people using Facebook because it brings something of value to their lives, often those puppy pictures or news of a cousin’s kid graduating from high school, right? Those are important things. They are not to be dismissed. There are also places in the world where Facebook is the entire media system, or at least the entire internet, places like sub-Saharan Africa, places like Myanmar, places like Sri Lanka, and increasingly in India, Facebook is everything. And we can’t dismiss that, as well. And so, we are—

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I mean, the government works with Facebook. For example, you talk about—

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: —Myanmar, Burma. It’s more expensive to get internet on your phone if you’re trying to access a site outside of Facebook.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s free to use Facebook services on your phone.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Right, Facebook—use of Facebook does not count against your data cap in Myanmar and in about 40 other countries around the world, the poorest countries in the world. So, the poorest places in the world are becoming Facebook-dependent at a rapid rate. This was—Facebook put this plan forward as a philanthropic arm. And one could look at it cynically and say, “Well, you were just trying to build Facebook customers.” But the people who run Facebook are true believers that the more people use Facebook for more hours a day, the better humanity will be. I think we’ve shown otherwise. I know my book shows otherwise. And I think we’ve built—we’ve allowed Facebook to build this terrible monster that is taking great advantage of the people who are most vulnerable. And it’s one reason I think we should pay less attention to what’s going on.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, but, Professor Vaidhyanathan, I think also, though, the importance of your book is that while you concentrate on Facebook, you make the point over and over again that it’s not just Facebook. I think in the conclusion to your book—I want to read a section where you talk about technopoly. And you say, “Between Google and Facebook we have witnessed a global concentration of wealth and power not seen since the British and Dutch East India Companies ruled vast territories, millions of people, and the most valuable trade routes.” And then you go on to say, “Like the East India Companies, they excuse their zeal and umbrage around the world by appealing to the missionary spirit: they are, after all, making the world better, right? They did all this by inviting us in, tricking us into allowing them to make us their means to wealth and power, distilling our activities and identities into data, and launching a major ideological movement”—what Neil Postman, the famous NYU critic, called technopoly. And then you go on to say, “'Technopoly is a state of culture. … It is also a state of mind. It consists of the deification of technology, which means that the culture seeks its authorization in technology, finds its satisfactions in technology, and takes its orders from technology.'” You could say this about Uber, about Airbnb, about all these folks that are saying that data and technology will save the world.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: That’s right. It’s a false religion. And what we really need is to rehumanize ourselves. That is the long, hard work. So, I can propose a few regulatory interventions, and they would make a difference, but not enough of a difference. Fundamentally, we have to break ourselves out of this habit of techno-fundamentalism—trying to come up with a technological solution to make up for the damage done by the previous technology. It’s a very bad habit. It doesn’t get us anywhere. If we really want to limit the damage that Facebook has done, we have to invest our time and our money in institutions that help us think, that help us think clearly, that can certify truth, that can host debate—right?—institutions like journalism, institutions like universities, public libraries, schools, other forms of public forums, town halls. We need to put our time and our energy into face-to-face politics, so we can look our opponents in the eye and recognize them as humans, and perhaps achieve some sort of rapprochement or mutual understanding and respect. Without that, we have no hope. If we’re engaging with people only through the smallest of screens, we have no ability to recognize the humanity in each other and no ability to think clearly. We cannot think collectively. We cannot think truthfully. We can’t think. We need to build—rebuild, if we ever had it, our ability to think. That’s ultimately the takeaway of my book. I hope we can figure out better, richer ways to think. We’re not getting rid of Facebook. We’re going to be with it—we’re going to have it for a long time. We might even learn to use it better, and we might rein it in a little better. But, ultimately, the big job is to train ourselves to think better.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Siva, let me ask you about WeChat in China. I mean, WeChat is everything there. It’s Yelp, PayPal, Google, Instagram, Facebook, all rolled into one. You write, “With almost a billion users, WeChat has infused itself into their lives in ways Facebook wishes it could.”

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re talking about a billion people using WeChat. How does it differ from Facebook? What does it mean? What does it tell us about the future?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Right. So, WeChat, as you said, is Facebook and everything else. Your phone might have 30 applications on it, might have 50 applications on it. You probably use six or seven regularly. If you lived and worked in China and had WeChat, you wouldn’t need all those applications. Your banking application, your library application, your retail application, all of these apps would be folded into WeChat. You can use WeChat at vending machines. You can use WeChat to make medical appointments. You can use WeChat to navigate daily life. Right?

Now, how is that different from Facebook? Well, it’s clearly what Facebook aspires to be. You may have noticed, if you’ve opened up the Facebook Messenger app on your phone, it has a number of micro-applications at the bottom—a Bank of America app, a Starbucks app, etc. That’s Facebook’s first foray into developing an application that works a lot like WeChat. It’s one of the reasons that Facebook is constantly nudging us to use Facebook Messenger more and more. Ultimately, I’m sure, they want WeChat—I mean, they want WhatsApp to become folded into Facebook Messenger, as well, and resemble it very strongly. So that’s their long-term strategy.

The other part of their long-term strategy is, Mark Zuckerberg wants to get into the Chinese market. That is the one place in the world where he can’t do business effectively. He would love to take on WeChat directly. But here’s the big difference. WeChat, like every other application or software platform in the People’s Republic of China answers to the People’s Republic of China. There is constant, full surveillance by the government. WeChat cannot operate without that. Facebook seems to be willing to negotiate on that point. If Facebook became more like WeChat, it’s very likely that around the world it would have to cut very strong agreements with governments around the world that would allow for maybe not Chinese level of surveillance, but certainly a dangerous level of surveillance and licensing. And so, again, we might not sweat that in the United States or in Western Europe, where we still have some basic civil liberties—at least most of us do—but people in Turkey, people in Egypt, people in India should be very worried about that trend.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: What about the issue, that’s been much publicized, of the role of Facebook and Twitter and other social media in protest movements, in dissident movements around the world, whether it’s in Egypt during the Tahrir Square protests or other parts of the world?

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: I think one of the great tragedies of this story is that we were misled into thinking that social media played a direct and motivating role in the uprisings in 2011. In fact, almost nobody in Egypt used Twitter at the time. The handful of people who did were cosmopolitans who lived in Cairo. And what they did, they used Twitter to inform the rest of the world, especially journalists, what was going on in Egypt. That was an important function, but it wasn’t used to organize protests. Neither was Facebook, really, for the simple reason that the government watches Facebook, right? The government watches Twitter. If you want to organize a protest out of the eyes of the government, the worst thing you can do is use Facebook or Twitter in that effort, right? In addition, when we think about the Arab Spring, the alleged Arab Spring, we often focus on—

AMY GOODMAN: Or the teachers’ protests here in the United States.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yes. So, this is what’s changed. A lot’s changed between 2011 and 2018. One is the fact that Facebook is now fairly universal. So now it has many millions of users in Egypt that it didn’t have in 2011. Facebook was new to Arabic in 2010, right? It just introduced its Arabic service in 2010. But by 2018, and certainly for the last few years—I mean, you can go back to the Occupy movements, which were not Facebook-driven but were Facebook-enhanced—you see that activists use Facebook very well. So, it’s true Facebook can be really valuable for motivation. You do not want to use Facebook in an authoritarian environment, though. That’s the important distinction. If you want to organize a teachers’ strike in the United States, you want to organize the Women’s March on Washington, D.C., you want to organize the tea party uprisings in the United States, Facebook is really great. Almost everybody in the U.S. is on Facebook. It’s wonderful for identifying like-minded people and motivating them. It’s, as I said, great for motivation, terrible for deliberation. A democratic republic needs both.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, but before we—

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Right now all we have is motivation.

AMY GOODMAN: Before we end the show, the issue of the state using it. I want to ask you about these recent reports that Memphis police used fake accounts to monitor black activists.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: The Guardian reports today, quote, “A trove of documents released by the city of Memphis late last week appear to show that its police department has been systematically using fake social media profiles to surveil local Black Lives Matter activists, and that it kept dossiers and detailed power point presentations on dozens of Memphis-area activists along with lists of their known associates.” The report reveals a fake Memphis Police Department Facebook profile named “Bob Smith” was used to join private groups and pose as an activist. We have just 30 seconds, Siva.

SIVA VAIDHYANATHAN: Yeah. Look, any police department, any state security service anywhere in the world that doesn’t infiltrate protest groups or, you know, activist groups that way is foolish, right? It’s so easy. Facebook makes surveillance so easy. My friends who do activism, especially human rights activism, in parts of the world that are authoritarian, the first thing they tell people is get off of Facebook. Use other services to coordinate your activities. Right? Use analog services and technologies. Right? Facebook is the worst possible way to stay out of the gaze of the state. It’s great for motivating people to get into the street, but don’t be surprised if there are a couple guys with crew cuts in the crowd with you.

AMY GOODMAN: Siva Vaidhyanathan, we want to thank you for being with us. His new book, Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy. Professor of media studies at the University of Virginia. That does is for our show. Also author of The Googlization of Everything.

Media Options