Guests

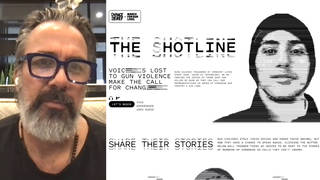

- Manuel Oliverfather of Joaquin Oliver.

- Patricia Olivermother of Joaquin Oliver.

Students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, return to class today, amid heavy security, after summer break. It was six months ago Tuesday when a former student, armed with a semiautomatic AR-15, gunned down 17 students, staff and teachers in just three minutes. It was one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history. After the horrific attack, many of the students who survived the shooting became leading activists for gun control. Among the students killed at Stoneman Douglas High School was Joaquin Oliver. On Tuesday, Democracy Now! spoke to Joaquin’s parents, Manuel and Patricia Oliver, who have started a new nonprofit called Change the Ref to promote the use of urban art and nonviolent creative confrontation to expose the disastrous effects of gun violence.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, returned to class today, amidst heavy security, after summer break. It was six months ago Tuesday when a former student, armed with a semiautomatic AR-15, gunned down 17 students, staff and teachers in just three minutes. It was one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history.

After the horrific attack, many of the students who survived the shooting became leading activists for gun control. In March, they led the historic March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C., where almost 800,000 people gathered. In May, a hundred days after the massacre, they held a die-in at a Publix grocery store to protest its donations to gubernatorial candidate Adam Putnam, a self-proclaimed “proud #NRASellout!” And in June, they launched a national Road to Change bus tour, where they registered young people to vote and to support gun control legislation. Their tour ended on Sunday in Newtown, Connecticut, the site of the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting massacre. They met with some of the Sandy Hook parents.

Among the students killed at Stoneman Douglas High School was Joaquin Oliver. He was born in Venezuela. On August 4th, on what would have been Joaquin’s 18th birthday, his parents helped organize a protest in Fairfax, Virginia, in front of the NRA headquarters. This is Joaquin’s father, Manny.

MANUEL OLIVER: We are in Fairfax, Virginia, and just in front of the NRA headquarters. Today is August 4th, and Joaquin would be turning 18, by—meaning that they will be having a lot of fun and probably celebrating that he was ready to go ahead and vote.

PROTESTERS: [singing] Happy birthday, dear Joaquin.

AMY GOODMAN: That powerful protest took place outside NRA headquarters on August 4th, Joaquin’s birthday. On Tuesday, I spoke to Joaquin’s parents, Manuel and Patricia Oliver, who have started a new nonprofit called ChangeTheRef.org to promote the use of urban art and nonviolent creative confrontation to expose the disastrous effects of gun violence. I began by asking Manny about the protest in front of the NRA.

MANUEL OLIVER: That day was pretty special. I got a call from our now good friend David Hogg. We fight together in this battle. And then he—

AMY GOODMAN: One of the outspoken students now fighting for gun control.

MANUEL OLIVER: Yes, yes. He’s one of the leaders of March for Our Lives. So, David told me that they were planning a rally in front of the NRA in Fairfax, Virginia, and he was wondering if I was OK to go there with Patricia and Andrea and kind of celebrate Joaquin’s birthday right in front of their faces. And I was totally OK with that idea. I think it was a brilliant way to have Joaquin making a statement in front of this group headquarter. So we did that. We went to Washington, then we went to Virginia. We did our wall, or wall number nine. And a lot of people was singing “Happy Birthday” to Joaquin. So, it was—

AMY GOODMAN: In front of NRA headquarters.

MANUEL OLIVER: Right in front of the NRA headquarters. And it’s interesting that being this like the headquarters, like the center of this whole gun lobby, if you want to say that way, there was only like 30 people from their side protesting what we were doing. At the same time, there was like 1,500 on our side. So that gives you the balance that we see every single day, every time we go to different places, of how the numbers are divided in this nation right now. There’s way more people on our side. That’s for sure.

AMY GOODMAN: And it’s not the first time you were in front of NRA headquarters. You went to confront the NRA in Dallas at their national convention, when President Trump and Vice President Pence went to speak.

MANUEL OLIVER: That was interesting, because we had—the NRA convention was in Dallas. So, we were there a week before the convention to plan where we were doing our wall, which is an action of demanding rights, basically, against gun laws. So, when we were there a week before, Trump still didn’t know if he was going to show to the convention. And for me, it was totally—I mean, why is he going to come here? Why is he supporting these people? And then, when I heard the news that he will be there with Pence and they will be together empowering this group, that’s when I added him to the wall. So the wall changed its graphic just because of his decision of being there. And I thought that, “OK, now that you’re going to be here, I’m going to use your image also in my rally, which is two blocks away from where you’re going to be.”

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain your tradition now of making murals. You’re an artist, Manny.

MANUEL OLIVER: I am, yes. I love art. That’s what I do. OK, I don’t know how to fight in any other way. I speak and draw. And there is a creative process behind these walls. It wasn’t planned to be happening, of course, this; our future should be way different than what we’re living right now. But so, we come to these places. We congregate people that follows our movement, and then we start drawing, on not permanent walls, images of Joaquin. This is a way to give Joaquin a voice still these days. And I do graffiti art style, so a lot of stencils. I research deep where we’re going and what’s happening in that location. And according to that, I will play around with some elements and make sure that Joaquin’s words are pretty loud and clear. We decided, me and Patricia, that Joaquin, besides being a victim, that he is, sadly but true, he will be an activist. And this is a way to do that. This is a way to bring the legend of Joaquin, right here, right now, very loud and clear, as one of the kids that is leading this amazing movement.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the first mural and what it said.

MANUEL OLIVER: First mural that we did said, “We demand a change.” And I thought about that, because I was—

AMY GOODMAN: And this was in Florida?

MANUEL OLIVER: This was in Wynwood, Florida, the design district. And I thought about that. It was very recent to the tragedy, and I was very sad. And there is a balance between being sad and being proactive and mad and being very activist, and sometimes sadness limits your emotions. So, that wall, it was a very hard experience, because I had no idea where I was going. I do remember that I had a hammer in my hand, and I was between being sad and mad. I just hit the wall. It was a drywall wall, a fake wall. And that sound of me hitting the wall made some of the people that were there run away from the room, because we were all expecting that a shooting could happen anywhere. It was a whole—

AMY GOODMAN: It just sounded like bullets.

MANUEL OLIVER: It sounded like a bullet, which is amazing. I discovered, that same moment, a way to impact people, which is, in other words, convincing fast. And I liked that, the option of impacting people instead of convincing people. So then I hit the wall 17 times. And then I had sunflowers, and I placed those sunflowers in those holes, like somehow honoring the victims from Parkland. So that became like the process of each wall. And the walls have been evolving. Now there are more—now it’s a combination. Now I’m not that sad. I’m more mad than sad. I became a little more—a better researcher of what’s going on. I’ve been educating myself: How do I fight this?

AMY GOODMAN: Manny Oliver, the father of Joaquin Oliver, one of 17 people—14 high school students—killed six months ago in the Valentine’s Day massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. When we come back, Manny and his wife Patricia will talk about Valentine’s Day and the day they became U.S. citizens along with Joaquin. It was Inauguration Day 2017. For our music break, we turn to a video put together by a family friend. It features Joaquin lip-synching to some of his favorite songs.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: That video, put together by a family friend, it features Joaquin Oliver lip-synching to some of his favorite songs. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. As students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, return to class today after summer break, we’re looking back at the Valentine’s Day shooting massacre six months ago, when a former student gunned down 17 students, staff and teachers in just three minutes. We are speaking to Manny and Patricia Oliver, the parents of 17-year-old Joaquin Oliver who died in the shooting. I spoke to them Tuesday. Manny talked about Joaquin’s final hours alive.

MANUEL OLIVER: The night before the tragedy—and this is a very nostalgic story. It’s really—it hurts, but I’ll share it again. Joaquin asked me to stop by and buy some flowers for his girlfriend, because it was going to be Valentine’s Day. So we bought them. And then, the day after, we—when I dropped Joaquin in school at 8:30 a.m., he said, “I love you, Dad.” “I love you, son.” And he was holding the sunflowers. And he was supposed to call me back to let me know how it go. I mean, we had that kind of relationship. So I told him, “Dude, you make sure you call me back, to see—so you can share Tori’s reaction with the flowers that we bought last night.” And he never called back. That was the last time that I had a chance to speak to my son. But I do know that Tori got the sunflowers. So, he had time to give them to Tori.

AMY GOODMAN: Patricia, you’re actually wearing those sunflowers. Is that right? You wear the sunflowers around your neck?

PATRICIA OLIVER: Yes, that’s true. Tori made us a little necklace. Together, you can see a heart. So she made it half and half for each of us, with one of the little flowers that she received that day. That was very nice of her. Very nice.

AMY GOODMAN: And you have one of them right there.

MANUEL OLIVER: It’s this right here, this right here.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, she sort of encased it in glass or plastic.

MANUEL OLIVER: Yes, in an epoxy.

AMY GOODMAN: One of those flowers.

MANUEL OLIVER: So these are the flowers that I bought with Joaquin the night before. So, the question here is—or one of the questions, one of the multiple questions that I’ve been asking to myself is—we did the right thing. We were raising our kid in a house full of love, that will buy flowers for Valentine’s Day. Him and his dad were buying flowers the night before. What was going on in that other house? What was the whole point of putting all those weapons together and those bullets together? What’s wrong in this society that that is an option, that while me and my son are buying flowers, some other people, that could be your neighbor, could be your family member, is just planning this terrible thing just to finish people’s life?

AMY GOODMAN: You won’t even say the shooter’s name?

MANUEL OLIVER: No. No, I don’t need to.

PATRICIA OLIVER: No, no, no.

MANUEL OLIVER: And you know why?

PATRICIA OLIVER: We don’t need to.

MANUEL OLIVER: Because there’s many of them. So, we cannot—this is not only an issue that happened in Parkland to Patricia and Manuel and Joaquin. Right now, while we’re talking, there’s another shooter planning to do this. Actually, maybe right now, someone just died because of this. So giving a name to a shooter is not necessary. It’s not fair to give numbers to victims and give names to shooters. So, that’s the reason why we don’t—it’s not that it’s hurting me at all. I mean, it’s just not the way to handle the situation.

AMY GOODMAN: So what is the answer?

MANUEL OLIVER: To solve the problem? Well, thank God we have a democracy, that I trust, and there’s a system, and we can vote for the people that will be able to fix this, hopefully. Besides educating ourselves in how we do what we do, we also have been educating ourselves in who we should trust and who is capable of fixing this. And I can tell you something. I’ve been searching for this dream team that can solve the problem. And answer number one or rule number one is that if any of these guys that is planning to be representing us is receiving money from the NRA, you’re out. You’re not cool. You can’t represent me, because you don’t have an impartial way of thinking. You are working like for a cartel. And as hard as it sounds, when you have a cartel, you put money into politicians’ pockets so they leave the law alone, so you can keep on with your business, make more money and kill more people.

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, right after the massacre, what made Parkland so different is how active you all became so quickly. When others, and particularly those involved with the NRA, like Donald Trump, are talking about thoughts and prayers—even the governor, Rick Scott—you all were mobilizing, the kids—led by the kids, and saying, “Nothing doing.” I remember at the March for Our Lives, one of the posters was “tots and pears,” and it was pictures of tater tots and pears. It said like, “No, that’s not where we’re headed.”

MANUEL OLIVER: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: They went to Tallahassee. You all went—you were involved with the legislation, writing the legislation. Is that right?

MANUEL OLIVER: We were involved. As much as we were—we agreed with being part of it, we have something in common. Seventeen families were going through pain. We lost our kids. Some people lost their parents. These are not only kids. This is 14 students, two teachers and one coach. So, we agree in some of the solutions. We don’t agree in others, but we respect each other a lot. So, I haven’t been to Tallahassee. Patricia hasn’t been to Tallahassee. We’re not those type of—that is not the way we’re handling our fact. We respect what they do. I haven’t been to Washington. The only day that we went to Washington was to draw a wall, to be an active, graphic message sender.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, you all—both of you became citizens years ago, from Venezuela, right? You moved to Florida. Talk about Joaquin becoming officially a citizen, your son. When was that?

PATRICIA OLIVER: That was last year, January 20th, 2017. He was very, very excited to become an official citizen, because he came—we came here the day after he turned 3 years old. So, in his heart, he was more American than Venezuelan, because he just learned how to grow up in the American culture, even though we have at home our own culture. So, he had the mixed combination of both cultures in general, which was very good for him. He was very proud of that. That day, he was so excited. He was so emotional. So he made like a review from when we went through, we went all these years, the process that we were growing as a—you know, as professionals, as—

AMY GOODMAN: And let’s make a point of what this day was, what you’re talking about. January 20th, 2017, the day that Joaquin became an American citizen, was also Inauguration Day for President Trump.

PATRICIA OLIVER: Oh, yes. Yeah, that was an especial—a unique day, because we became citizens very early in the morning. That happened at 8:00 in the morning, 8:30, and at 11:00—

AMY GOODMAN: Where were you?

PATRICIA OLIVER: We were at the place that there is a immigration center, that they have there a huge room there, where they’re celebrating the citizenship. We were quite—maybe 200 people receiving the citizenship. And they play a video with the current president. At that moment or at that time exactly, it was Obama.

AMY GOODMAN: Because that was the morning—

PATRICIA OLIVER: Yeah, it was.

AMY GOODMAN: —of Inauguration Day.

PATRICIA OLIVER: Yeah, 8:30 in the morning, at 8:30. So, it was still Obama in power. And he gave us the “welcome to America.” So that was very exciting.

AMY GOODMAN: And three hours later—

PATRICIA OLIVER: And three hours later, we had a new president.

AMY GOODMAN: And the three of you became citizens that day?

PATRICIA OLIVER: Yeah, we became citizens, because Joaquin’s a minor. Joaquin was 16 at that time, so we were automatically, the three of us, we were citizens.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about Graduation Day, Patricia.

PATRICIA OLIVER: Well, Graduation Day was a very hard day, because, you know, every kid, especially Joaquin, in my case, was just dreaming about that day. So, he was—like, you know, any other family, we were planning about future, about schools, about where to go, how we were going, what do you like most. And, you know, that just—it didn’t happen. So, he was very committed to be going to that day. And he loved to write a lot, so he made this note once where he’s saying, “Once I get my diploma, I will see straight to my mom’s eyes and saying, 'I made it.'”

So, we were at home. We were debating, you know, about Graduation Day. So we decided that—our daughter, Manuel and me, we decided that the person that it was the best one to be receiving the diploma was me. So, I was—I got to prepare myself emotionally. It took a while. It took something to be there. And I said, “Well, I have to do what I have to do. I have to make Joaquin happy, because I know that he will be very proud of me being up there on stage receiving the diploma.” But we also decided to not only receiving the diploma, we have to make a statement. We have to take advantage of the moment to make people understand that this can’t be happening again and again and again. So that’s why I—

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what you wore.

PATRICIA OLIVER: I was—we decided to make this jersey, because Joaquin was very into sports. And we decided to make a jersey to make the—you know, to make the statement very clear. And that was a goalie shirt, a goalie jersey shirt, but it was saying, “This should be my son.”

AMY GOODMAN: So, there’s the T-shirt of you. You’re holding up his diploma.

PATRICIA OLIVER: Yes. They frame it.

AMY GOODMAN: And your yellow T-shirt says, “This should be”—

PATRICIA OLIVER: “My son.”

AMY GOODMAN: —”my son.” Two weeks after the massacre at Parkland, President Trump urged Republican and Democratic lawmakers to pass comprehensive gun control measures and accused Pennsylvania Republican Senator Pat Toomey of being afraid of the NRA.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Think of it. You can buy a handgun. You can buy one, but you have to wait 'til you're 21. But you can buy the kind of weapon used in the school shooting at 18. I think it’s something you have to think about.

SEN. DIANNE FEINSTEIN: Would you sign that?

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: So, I’ll tell you what: I’m going to give it a lot of consideration. And I’m the one bringing it up, and a lot of people don’t even want to bring it up, because they’re afraid to bring it up. But you can’t buy a handgun at 18, 19 or 20. You have to wait 'til you're 21. But you can buy the gun, the weapon used in this horrible shooting, at 18. You are going to decide. The people in this room, pretty much, you’re going to decide. But I would give very serious thought to it. I can say that the NRA is opposed to it. And I’m a fan of the NRA. I mean, there’s no bigger fan. I’m a big fan of the NRA. They want to do it. These are great people. These are great patriots. They love our country. But that doesn’t mean we have to agree on everything. It doesn’t make sense that I have to wait 'til I'm 21 to get a handgun, but I can get this weapon at 18. I don’t know. So I was just curious as to what you did in your bill.

SEN. PAT TOOMEY: We—

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: You don’t address it.

SEN. PAT TOOMEY: We didn’t address it, Mr. President. Look, I think the—

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: You know why? Because you’re afraid of the NRA, right?

SEN. PAT TOOMEY: No, it’s not an issue. But…

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: It’s a big issue right now, and a lot of people are talking about it. But a lot of people—a lot of people are afraid of that issue, raising the age for that weapon to 21.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that is President Trump saying, “Don’t be afraid of the NRA.”

MANUEL OLIVER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Did he do any of this that he’s talking about?

MANUEL OLIVER: I love it how he points at people, like blaming everybody. And I love also the way he says, “I’m going to have to think about this.” Like, dude, there is nothing to think about this.

PATRICIA OLIVER: To think about.

MANUEL OLIVER: This is happening already. After that, he was at the NRA convention empowering this group. And he has never been in Parkland. By the way, I don’t need him to go to Parkland. I don’t think he’s going to—

AMY GOODMAN: You mean he never came to Parkland, Florida.

MANUEL OLIVER: That is another culture—never came to Parkland. I invited him publicly to Parkland. I said, “Now that you haven’t invited me to the White House, let’s do this in another way. How about you, in one of those trips to Mar-a-Lago, driving 30 minutes or 25 minutes to Parkland? And I want you to spend five minutes in Joaquin’s room, in Joaquin’s empty room, so maybe you have an idea of what’s going on in many houses, in many families around the nation.” Of course that was ignored. That’s fine. But—

AMY GOODMAN: You put that invitation out, because Mar-a-Lago—

MANUEL OLIVER: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: —is pretty much just down the road.

MANUEL OLIVER: Absolutely.

PATRICIA OLIVER: Oh, yes, definitely.

MANUEL OLIVER: By the way, that invitation was in all media. He got that. He ignored it. But he knows I’m not a pro-, and Joaquin wasn’t a pro-Trump person at all. And I have writings from Joaquin that show—

AMY GOODMAN: Can you share any of Joaquin’s writings?

MANUEL OLIVER: Sure. I have—actually, I have something right here that I can read you. It is pretty impactful. So, “Ok guys I’ve had it, I wanna ask every one of my 'true' friends who support Donald Trump if they could live without me. If I vanished today would you be happy? Would you be okay with that? Not even just me but anyone being discriminated by your president. Would you guys be 100% okay with your immigrant friends never existing in your life? And those who choose to stay out of it are just as bad. If you stay quiet you’re supporting him. So fight for us and we’ll fight for you. Love us and we’ll love you. Take us in with open arms and we’ll make sure we make the best out of our stay here.”

AMY GOODMAN: And that’s the words of your son, Joaquin Oliver.

MANUEL OLIVER: This is my son, Joaquin Oliver. So, whoever thinks that me and Patricia are leading our own fight, they should know that we’re leading Joaquin’s fight.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that was a tweet of Joaquin’s—

MANUEL OLIVER: This is Joaquin writing, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —in the midst of the whole debate on immigration and Trump’s attacks on immigrants.

MANUEL OLIVER: While that—yes, yes. The other one that I have shows—which is before that, also written by Joaquin. This is dated 12 December 2013. “Dear U.S. gun owner, I am writing this letter to talk to you about how we’re going to solve this gun law movement. Most of you have a problem with the idea of a universal background check. Why are you mad that there is a background check? It’s for your own good. Maybe you’re fond of having crazy people with death machines. Shouldn’t have anything against background checks if you’re innocent. Thank you, Joaquin, Coral Springs.” He was 13 years.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, Patricia, your thoughts, as you head back to Florida, what this period, with this six months, if you feel that you are beginning to heal, if that’s possible?

PATRICIA OLIVER: Well, it feels that it happened just yesterday. So, I think that’s—I’ve been meeting some other people in these same circumstances, and I think every day is a different day, and I see from them that, you know, they’re just reviving in the moment like it was a minute ago. So, I think we have to go. We have to keep going, when we are doing, that it brings you or bring us some relief, that we feel that we’re doing something for other kids and for other people, because we are all suffering of this terrible situation that is the lack of gun control. So, that’s what I think about, talking about me, that it makes me feel better, in a way, that I can do something for somebody else.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Manny, the six months for you? Also your daughter, because Joaquin has an older sister, Andrea.

MANUEL OLIVER: Yeah, the six months for me is just the amount of time that I’ve been fighting, and it’s not enough. There’s two ways of looking at time in these situations: Oh, my god, it’s already six months; it’s a short time to get used to the situation, but it’s also been very short for our fight. Since a week after what happened, I’ve been—and we go back to what we carry, and I carry this little stone that I found in Joaquin’s memorial across the school. And it goes, “We will change the world for you.” And that’s what I try to do every single day.

AMY GOODMAN: Manny and Patricia Oliver, remembering their son, Joaquin Oliver, one of 17 people killed six months ago in the Valentine’s Day massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. Students at MSD return to the school today, after summer break. Joaquin would have been 18 on August 4th.

This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. When we return, 559 children remain separated from their parents, separated by the U.S. government. What will happen to them? Where are their parents? Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School performing in June during the Tony Awards, singing “Seasons of Love” from the hit Broadway musical Rent.

Media Options