Topics

Guests

- Oprah Winfreylegendary broadcaster and media executive, entrepreneur and philanthropist.

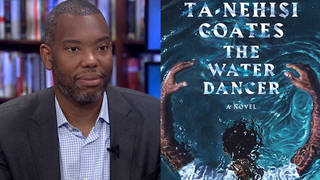

Last Thursday, literary luminaries and social leaders from around the country gathered at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan to honor Toni Morrison, one of the nation’s most influential writers. She died in August at the age of 88 from complications of pneumonia. In 1993, Morrison became the first African-American woman to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. She also won a Pulitzer Prize in 1988 for her classic work “Beloved.” Much of Morrison’s writing focused on the black female experience in America, and her writing style honored the rhythms of black oral tradition. In 2012, President Obama awarded Morrison the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Ta-Nehisi Coates, Edwidge Danticat and Oprah Winfrey were among those who spoke about Toni Morrison’s life and legacy. We air Oprah’s eulogy.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We want to turn to the incredible legacy of Toni Morrison. Last week, literary luminaries and social leaders from around the country gathered at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan to honor Morrison, one of the nation’s most influential writers. She died in August at the age of 88 from complications of pneumonia. In 1993, Morrison became the first African-American woman to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. She’s also won a Pulitzer Prize in 1988 for her classic work Beloved. Much of Morrison’s writing focused on the black female experience in America, and her writing style honored the rhythms of black oral tradition.

AMY GOODMAN: In 2012, President Obama awarded Toni Morrison the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Well, at St. John the Divine, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Edwidge Danticat and Oprah Winfrey were among those who spoke about Toni Morrison’s life and legacy. Oprah Winfrey was the last speaker of the evening.

OPRAH WINFREY: The first time I came face to face with Toni Morrison was in Maya Angelou’s backyard for a gathering of some of the most illustrious black people you’ve ever heard of, to celebrate Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize victory. My head and my heart were swirling. Every time I looked at her, I mean, I couldn’t even speak. I had to catch my breath.

And I was seated across from her at dinner, and there was a moment when I saw Ms. Morrison just gesture to the waiter for some water, and I almost tripped over myself trying to get up from the table to get it for her. And Maya said, “Sit down. We have people here to do that. You’re a guest.” So I sat down. I obeyed, of course.

But it was not easy, I tell you, to sit still or to keep myself inside my body. I felt like I was all of 7 years old, because, after all, she was there — and so many others that day: Mari Evans, Sister Angela Davis was there, Nikki Giovanni was there, Rita Dove was there, Toni Cade Bambara was there. It was a writers’ mecca. And I was there sitting at the table taking it all in. And as I look back, that day remains one of the great thrills of my life.

You know, I didn’t really get to speak to Toni Morrison that day. I was just too bedazzled. But I had already previously called her up to ask about acquiring the film rights to Beloved. After I finished reading it, I found her number, called her, and when I asked her, “Is it true that sometimes people have to read over your work in order to understand it, to get the full meaning?” and she bluntly replied, “That, my dear, is called reading.” I was embarrassed. But that statement actually gave me the confidence, years later, when I formed the book club on the Oprah show, to choose her work. I chose more of her books than any other author over the years — _Song of Solomon_ first, Sula, The Bluest Eye and Paradise. And if any one of our viewers ever complained that it was hard going or challenging reading Toni Morrison, I simply said, “That, my dear, is called reading.”

There was no distance between Toni Morrison and her words. I loved her novels. But lately I’ve been rereading her essays, which underscore that she was also one of our most influential public intellectuals. In one essay, she said, “If writing is thinking and discovery and selection and order and meaning, it is also awe and reverence and mystery and magic.” And this: “Facts can exist without human intelligence, but truth cannot.” She thought deeply about the role of the artist and concluded that writers are among the most sensitive, most intellectually anarchic, most representative, most probing of all the artists. She believed it was a writer’s job to rip the veil off, to bore down to the truth. She took the canon, and she broke it open. Among her legacies, the writers she paved the way for, many of them here in this beautiful space tonight celebrating her.

Toni Morrison was her words. She is her words, for her words often were confrontational. She spoke the unspoken. She probed the unexplored. She wrote of eliminating the white gaze, of not wanting to speak for black people but wanting to speak to them, to be among them, to be among all people. Her words don’t permit the reader to down them quickly and forget them. We know that. They refuse to be skimmed. They will not be ignored. They can gut you, turn you upside down, make you think you just don’t get it. But when you finally do, when you finally do — and you always will when you open yourself to what she is offering — you experience, as I have many times reading Toni Morrison, a kind of emancipation, a liberation, an ascension to another level of understanding, because by taking us down there amid the pain, the shadows, she urges us to keep going, to keep feeling, to keep trying to figure it all out, with her words and her stories as guide and companion. And she asks us to follow our own pain, to reckon with it and, at last, to transcend it.

And while she’s no longer on this Earth, her magnificent soul, her boundless imagination, her fierce passion, her gallantry — she told me once, “I’ve always known I was gallant.” Who says that? Who even knows they are gallant? Well, her gallantry remains always to help us navigate our way through.

I’d like to close the evening with an excerpt from Song of Solomon. You know, I have many favorite passages when it comes to Toni’s body of work. One that you just shared, Kevin, “She is a friend of my mind” from Beloved, I love that. “Mamma, did you ever love us?” and the mother’s response in Sula. But this one from Song of Solomon never fails to inspire awe for me. And for that and so much else, I say thank you to this singular, monumental, gallant writer.

“He had come out of nowhere, as ignorant as a hammer and broke as a convict, with nothing — nothing — but free papers, a Bible, and a pretty black-haired wife, and in one year he’d leased ten acres, the next ten more. Sixteen years later he had one of the best farms in Montour County. A farm that colored their lives like a paintbrush and spoke to them like a sermon. 'You see? You see?' the farm said to them. 'See? See what you can do? You see? Never mind you can't tell one letter from another, never mind you born a slave, never mind you lose your name, never mind your daddy dead, never mind nothing. Here, this here, is what a man can do if he puts his mind to it and his back in it. Stop sniveling,’ it said. 'Stop picking around the edges of the world. Take advantage, and if you can't take advantage, take disadvantage. We live here. We live here! On this planet, in this nation, in this county. Can’t you see that? Can’t you see? We got a home right here in this rock, don’t you see! We got a home in this rock, and if I got a home you got one too! So grab it. Grab this land! Take this land, hold this land, my brothers. Ain’t nobody crying in my home. I want you to take this land, make it, my brothers, shake it, squeeze it, turn it, twist it, beat it, kick it, kiss it, whip it, stomp it, dig it, plow it, seed it, reap it, rent it, buy it, sell it, own it, build it, multiply it, and pass it on — you hear me? Do you hear me? Pass it on!’”

Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Oprah Winfrey, remembering the great writer Toni Morrison at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan. The Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning writer died in August at the age of 88.

That does it for our show. Tune in to our Thursday and Friday specials. On Thanksgiving, we’ll speak to the indigenous scholar and activist Nick Estes, citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe and author of Our History Is the Future. Then we’ll hear from acclaimed writer Arundhati Roy on the crisis in Kashmir and growing authoritarianism in India and around the world.

On Friday, we’ll bring you a special hour with the legendary musician and artist David Byrne. He’ll talk about his time in the Talking Heads, his years of bike advocacy, reasons to be cheerful and his new hit Broadway show American Utopia.

Media Options