In a move that could reshape the world’s financial system, Facebook has unveiled plans to launch a new global digital currency called Libra. Facebook announced its plans on Tuesday after secretly working on the cryptocurrency for more than a year. It will launch Libra next year in partnership with other large companies including Visa, Mastercard, PayPal and Uber. Facebook said it wants to create “a simple global currency and infrastructure that empowers billions of people.” The plan has already come under fierce criticism from financial regulators and lawmakers. Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown tweeted, “Facebook is already too big and too powerful, and it has used that power to exploit users’ data without protecting their privacy. We cannot allow Facebook to run a risky new cryptocurrency out of a Swiss bank account without oversight.” We speak with David Dayen, the executive editor of The American Prospect. He recently wrote a piece for The New Republic headlined “The Final Battle in Big Tech’s War to Dominate Your World.”

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: In a move that could reshape the world’s financial system, Facebook has unveiled plans to launch a new global digital currency called Libra. Facebook announced its plans Tuesday after secretly working on the cryptocurrency for more than a year. It plans to launch Libra next year in partnership with other large companies—among them, Visa, Mastercard, PayPal and Uber. Facebook said it wants to create, quote, “a simple global currency and infrastructure that empowers billions of people.” David Marcus, Facebook’s cryptocurrency chief, appeared on CNBC on Tuesday.

DAVID MARCUS: If you want to compare Libra with traditional cryptocurrencies, the first thing and the first big difference is that typically cryptocurrencies are investment vehicles or, you know, investment assets rather than being great medium of exchange. And this is really designed, from the ground up, to be a great medium of exchange, a very high-quality form of digital money that you can use for everyday payments and cross-border payments, microtransactions and all kinds of different things.

AMY GOODMAN: Facebook’s plan has already come under fierce criticism from financial regulators and lawmakers. French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said Libra must not become a sovereign currency. In Washington, the chair of the House Financial Services Committee, Congressmember Maxine Waters, called on Facebook to pause its development of Libra until lawmakers and regulators have an opportunity to examine these issues and take action. Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown tweeted, quote, “Facebook is already too big and too powerful, and it has used that power to exploit users’ data without protecting their privacy. We cannot allow Facebook to run a risky new cryptocurrency out of a Swiss bank account without oversight,” Brown said.

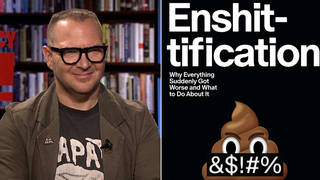

To talk more about Facebook’s plans for a new digital currency, we’re joined by David Dayen. He is executive editor of The American Prospect, recently wrote a piece for The New Republic headlined “The Final Battle in Big Tech’s War to Dominate Your World.”

Welcome to Democracy Now! Talk about these major developments, David Dayen. Explain exactly what Libra is and what Facebook is trying to do.

DAVID DAYEN: So, Libra, as Facebook describes it, is a currency, a cryptocurrency. When you talk about that, you kind of think of something like bitcoin. But this would actually have reserves, so they call it sort of a stable coin. It is backed by actual money that is various international currencies and also government securities. And so, that should prevent volatility from the unit of exchange, Libra, going up or down very much. It will fluctuate a little, but not in the ways that, you know, we think of when we think of bitcoin. So, according to Facebook, that is the way that this can be used to purchase goods on the Facebook app or on any other app or website that offers payment in Libra. It’s a way to transfer money to other people on the Facebook app. Obviously, you know, we have, what, over 2 billion people that use Facebook. It’s a way to transfer something of value between those users. And because it’s backed by international currencies and can be used across borders, it’s really supplanting the need to exchange money. You don’t have to go from dollars to euros, necessarily; you can just pay in Libra. So, that’s sort of the pitch that Facebook would make.

The other side of this is that there’s no real regulatory setup. It’s displacing global currencies in some ways. There are serious monetary policy concerns, serious regulatory concerns. Could this be used to facilitate money laundering or tax evasion? There are a whole host of unanswered questions around this.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, David Dayen, this whole issue of a bunch of private companies, because we’re not talking just about Facebook. They initiated it, but they’ve gotten a buy-in from credit card companies, from PayPal, from Uber, from a variety of very powerful companies, mostly American companies. And you’re, in essence, creating a private organization to run a money system that would stretch across borders. I spent a couple of hours going on their website yesterday, trying to understand even the governance situation of this, and it’s very detailed. They’ve been working on this, obviously, for quite some time in secret. And they talk about creating a Libra Association Council, where if you were going to be a founding member, you have to invest at least $10 million, and supposedly no one company could control this council, because you’d be limited to a 1% voting share, no matter how much money you invested. But if you invest a lot of money, you can designate universities or nonprofits to vote for you on this council. So, in effect, the more money you invest, even though you may not have direct power over how the association functions, you can still have enormous influence on the voting blocs of what would in essence be a new international currency. I’m wondering what—

DAVID DAYEN: Yeah, I mean—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: What are regulators going to say about this?

DAVID DAYEN: Yeah, there are serious governance questions around it. There are also, you know, financial questions. I mean, the way that this works, as I understand it, is there’s this investment of $10 million from up to a hundred companies, so you’re talking about a billion dollars. And also, all the money—so, if somebody buys Libra, they’re paying that money into this reserve, and they get Libra back. That money can be used to be invested, these reserves, Facebook says, in very low-risk securities, but that money is not returned to the individual. So, if you think about a bank, you get interest on your money that you deposit with the bank, that the bank can use for any purpose that they wish. In this case, the interest stays with these companies. So, you know, there’s a financial incentive for these companies to get involved in this.

And if you think about the scale, the potential scale of something like this, where you’re talking about 2 billion users, any—this is almost an operating system for money. Any other organization can build something to create payment services in this fashion. The possibilities are really endless, and so, you know, the financial possibilities are also endless. And as you correctly cite, Juan, I mean, the governance questions of how this currency will be managed, how capital flows will be understood and facilitated, if you have a country that is experiencing an economic downturn and—Libra is an excellent way for capital flight, which is something we don’t really want when a country is in financial trouble. How is that going to be mitigated or managed? There are just, as I said, just way too many unanswered questions with this.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what about the issue, for instance, of countries that may be in conflict with each other—the United States and Iran right now or the United States and Venezuela? The impact of this kind of a currency on the geopolitical conflicts and the ability of nations to control their own currencies?

DAVID DAYEN: Yeah, I mean, it’s hard to know how sanctions would work under this setup. It’s hard to know how any kind of anti-money-laundering—usually a bank would have to create some suspicious activity report. Will Libra be able to do that? You know, you could use this for ways to harm other countries through removing that currency into Libra. I mean, that would obviously be done at the individual level. But, you know, usually, as you say, countries are in control of their own fiat currency. And if they have this sort of safety valve, this global currency that would displace them in some ways, which an individual could use to make all the purchases that it needs to make, and not use the currency denominated in that particular country, it’s almost unknown. I mean, we’d have no precedent for this. So, it’s hard to say what some of the implications would be. And I think that’s why regulators and politicians are asking to really slow down, so this can sort of be studied.

AMY GOODMAN: On Tuesday, Facebook released a promotional video highlighting what the company sees as possible benefits of the new currency.

>> What if everyone was invited to the global economy with access to the same financial opportunities? Introducing Libra, a new global currency, designed for the digital world, backed by the belief that money should be fast for Ope in Lagos, simple for Saul’s family business in Manila, and secure for Betsabé when sending money home to Mexico City. It’s powered by blockchain, making it safe and accessible, no matter who you are or where you’re from.

AMY GOODMAN: So, David Dayen, executive editor of The American Prospect, if you can respond to this, and also why Libra will be based in Switzerland? Does it have to do with it being a banking center, a tax haven?

DAVID DAYEN: Yeah. So, I mean, the truth is, is that if you were able to create some sort of digital wallet that could be used in any country and purchase and make microtransfers and things like that, it would be convenient. I mean, that’s really what Facebook is banking on, right? I mean, right now the U.S. payment system is pretty clunky, particularly with international transfers, that take several days to clear. There would be a convenience angle here.

And, of course, Facebook believes that if they can get you on their website and using their digital wallet, which they control directly—I mean, there’s this Libra Association that’s based in Switzerland, as you say, probably for tax purposes, that is controlling the governance of the currency. But Calibra, which is what David Marcus, who we heard from at the top, is running, is a digital wallet that’s run by a subsidiary that’s wholly owned by Facebook. So, if Calibra becomes ubiquitous, if it becomes this thing that you really need to make purchases, then you have something like WeChat. And WeChat is the app in China that has become so much a part of people’s lives that it’s very hard to use paper money in China. I mean, this is a social media app, it’s a chat tool, and also it’s a purchase app. It’s something that you can use in that fashion.

And that’s Facebook’s, I think, end goal. If you add payments onto this social media application that is incredibly dominant, you’ve basically locked people into Facebook. And if you’ve done that, then, you know, whether you’re taking a little bit out of every transaction that 2 billion people make on a daily basis, or whether you are just locking people onto the site, knowing what purchases they’ve made and then selling very data-rich ads based on that, you have a prospect of real domination. And, you know, I really think that either this thing is going to not get off the ground, because too many regulators and politicians will have uneasiness about it, or we’ll look back in 20 years, and this will be the week where this thing was announced that created this dominant global company that is, you know, an indispensable digital partner kind of walking you through life.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, David Dayen, the whole issue of security. Facebook is currently a poster child for the violations of privacy data rights of individuals. They’re insisting that they’re going to build a—this Calibra will be a separate subsidiary, that it won’t share the user information of Facebook itself with this payment system that they set up. Could you talk about this issue? Because it almost seems like—or, it does seem like Facebook is basically transferring its monopoly position in social media to then enter the financial transactions world.

DAVID DAYEN: Yeah. I mean, first of all, do you trust Mark Zuckerberg with anything around privacy at this point, after years and years of these revelations? And second of all, it’s a bit of a red herring. So, it’s entirely possible—let’s take Facebook at their word—that the financial data and the social data will be separate. Well, in order to access purchases on Libra, you’re still going to have to make a click within the Facebook app or within WhatsApp or wherever, to find your purchase or to search for a business that you want to solicit or things like that. And that information is certainly going to be available to Facebook. So, the idea that there’s no, you know, extra data that you’d be grabbing here, if you’re Facebook, is really not true. I mean, if you’re spending more time on the app, if you’re clicking around to find things to buy on the app, which is not typically at this point what people do on Facebook, then that’s just much more data that Facebook is going to be able to use to target ads at you and do whatever else it wants.

AMY GOODMAN: So, finally, again, the title of your piece, “The Final Battle in Big Tech’s War to Dominate Your World,” fill that out.

DAVID DAYEN: Sure. So, we’ve been seeing, over the last several months, the big tech companies—Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook—try to figure out how to become that sort of one partner. I mean, you have Apple, that put out this thing that’s a credit card, called the Apple Card. You have Amazon partnering with other global payment systems on what they call World Pay—or, what they call Amazon Pay, I should say. Google has its own digital wallet. And now you have Facebook with this thing that is—who knows what it is? Is it a bank? Is it a prepaid card? Is it a digital wallet? Is it a global currency? So you have all these companies, that were kind of competing separately, are now all moving into the payment space and also moving into other spaces that are overlapping, like entertainment, to become that thing that is sort of the only kind of digital tool that you will need. So you can make all of your purchases, you can talk to all your friends, you can access all your entertainment, you can do everything that you wish inside this world, whether it’s Facebook, Google, Amazon or Apple.

And that’s really their intention. And that’s why I call it sort of the war of all against all. This is like the final battle for global domination here. And, you know, how that shakes out is sort of indeterminate at this point, but what we know is that if you’re creating this—we already have these companies that are monopolies in their own sort of personal spaces—if they combine sort of together a lot of different options for you as an individual, then you have just this absolute dominant behemoth. And, you know, there are serious concerns around giving that much power to one company.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, of course, we’ll continue to follow this, David Dayen, executive editor of The American Prospect. We’ll link to your piece in The New Republic, “The Final Battle in Big Tech’s War to Dominate Your World.”

Coming up, we go to Arizona to speak with an African-American family held at gunpoint by police because their 4-year-old daughter allegedly took a doll from a Family Dollar store. They’re now talking about suing for $10 million. But first we look at a highly contested district attorney’s race here in New York, in Queens, where one of the candidates is making headlines by vowing to radically reshape the criminal justice system. Her name is Tiffany Cabán. She’s with us. Stay with us.

Media Options