Topics

Guests

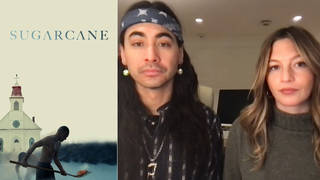

- Marion Bullerchief commissioner of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and a member of the Mistawasis First Nation in Saskatchewan.

- Robyn Bourgeoisassistant professor in the Centre for Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University.

A chilling national inquiry has determined that the frequent and widespread disappearance and murder of indigenous girls and women in Canada is a genocide that the government itself is responsible for. The findings were announced by the Canadian National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls at a ceremony on Monday with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the families of victims. Many in the audience held red flowers to commemorate the dead. The national inquiry was convened after the body of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine from the Sagkeeng First Nation was found in the Red River in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 2014. The report follows decades of anguish and anger as indigenous communities have called for greater attention to the epidemic of dead and missing indigenous women, girls and two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual people. Some 1,500 family members of victims and survivors gave testimony to the commission, painting a picture of violence, state-sanctioned neglect, and “pervasive racist and sexist stereotypes” that led nearly 1,200 indigenous women and girls to die or go missing between 1980 and 2012. Indigenous activists say this number could be a massive undercount, as many deaths go unreported and unnoticed. We speak with Marion Buller, chief commissioner of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, and Robyn Bourgeois, assistant professor in the Centre for Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We begin today’s show in Canada, where a devastating national inquiry has determined that the frequent and widespread disappearance and murder of indigenous girls and women is a genocide that the Canadian government itself is responsible for. This chilling conclusion was reported by the Canadian National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls at a ceremony on Monday with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the families of victims. Many in the audience held red flowers to commemorate the dead. This is Marion Buller, the chief commissioner of the inquiry, speaking at the ceremony, which was held at the Canadian Museum of History.

MARION BULLER: The significant, persistent and deliberate pattern of systemic racial and gendered human and indigenous rights violations and abuses, perpetuated historically and maintained today by the Canadian state, designed to displace indigenous people from their lands, social structures and governments, and to eradicate their existence as nations, communities, families and individuals, is the cause of the disappearances, murders and violence experienced by indigenous women, girls, 2SLGBTQQIA people, and this is genocide.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The inquiry issued 231 recommendations on how to address the deaths. At the same ceremony, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to conduct a thorough review of the report.

PRIME MINISTER JUSTIN TRUDEAU: Time and again, we have heard of their disappearance, violence or even death being labeled low priority or ignored. We have heard of their human rights being consistently and systematically violated. It is shameful. It is absolutely unacceptable. And it must end. …

To the missing and murdered indigenous women and girls of Canada, to their families and to survivors, we have failed you. We will fail you no longer. In the days ahead, let us walk forward together as partners, hand in hand, as we right these wrongs and seek justice for the indigenous people of Canada.

AMY GOODMAN: The report follows decades of anguish and anger as indigenous communities have called for greater attention to the epidemic of dead and missing indigenous women, girls and two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual people. Fifteen hundred family members of victims and survivors gave testimony to the commission, painting a picture of violence, state-sanctioned neglect, and pervasive racist and sexist stereotypes that have led to nearly 1,200 indigenous women and girls to die or go missing between 1980 and 2012. That number could be a massive undercount: Indigenous activists say many deaths go unreported and unnoticed. The national inquiry was convened after the body of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine from the Sagkeeng First Nation was found in the Red River in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 2014.

For more, we’re joined by two guests. In Ottawa, we’re joined by Marion Buller, the chief commissioner of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. She is Cree and a member of the Mistawasis First Nation in Saskatchewan. Marion Buller is a retired indigenous judge, was British Columbia’s first-ever female indigenous judge. And in Vancouver, we’re joined by Robyn Bourgeois, a mixed-race Cree academic and activist. She is an assistant professor in the Centre for Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University, where her work focuses on indigenous feminism, violence against indigenous women and girls, and indigenous women’s political activism and leadership.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Chief Commissioner Marion Buller, if you can start off by laying out for the world, for our global audience, how this inquiry began, this National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, and your chief findings? And how long did this take?

MARION BULLER: We started this national inquiry back in September of 2016. And over—oh, gee, how many years and months now, I’ve lost track—we’ve heard from families and survivors, from coast to coast to coast, about their experiences with the Canadian state—more often than not, the police. But we also heard a lot about shortcomings in the child welfare system, education, health, other areas of government services. Then we had to do our final report to government. We did do an interim report in 2017, but our final report is the one that was just released. It’s about 1,200 pages long.

Our chief findings are, amongst others, the finding of genocide, as you’ve recorded earlier. We have also found that there have been human rights and indigenous rights violations perpetuated over generations. We have also found that governments have deliberately underfunded or improperly delivered services to indigenous people.

All across Canada, we found, as well, that indigenous women and girls are targeted by perpetrators of violence, targeted all across Canada. And so, there have to be changes to our criminal justice system and our judicial system to right those wrongs, to denounce and deter the horrendous amount of violence against indigenous women and girls. We have been told by perpetrators of violence that they target indigenous women and girls because they can. They can get away with it. Even if it gets to court, the sentence will just be a slap on the hand.

We’ve also heard about children be removed from their families. And we’ve made findings of fact about the children welfare system, that children are removed from families not because the parents are incompetent or negligent. It’s because the parents are poor. And the parents are poor because the state delivery of services and because of the genocide that’s been going on in Canada for generations now.

So, policing, criminal justice, child welfare, indigenous rights breaches and abuses, human rights abuses and violations—all of them—I think that’s about the best summary I can give you in a short period of time.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Chief Commissioner Buller, could you talk about how the report was pulled together? It’s over a thousand pages long. How did you compile the information during the process of your investigation?

MARION BULLER: We have still probably one of the most amazing research teams, led by Dr. Karine Duhamel, who is indigenous herself. They did an incredible amount of work to marshal the evidence that we heard, to make sure that we were coming from a very sound and strong position legally and from a research point of view, a social science point of view, as well. We knew—by the time we had finished hearing from families and survivors, we knew what the issues were. We knew the problems that we had to address. But our research team provided a wonderful foundation for us to move forward.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And when you talk about genocide, most people associate genocide against a particular group with conscious, deliberate actions of a government to directly kill or murder people. Could you talk about the legal understanding that you put together to declare that Canada has been involved in genocide?

MARION BULLER: Well, you are correct. Most of us, myself included, before I started this work, thought that genocide was something like the Holocaust or the Rwanda massacres, massacres of people that have occurred elsewhere in very short periods of time, relatively speaking.

The genocide that has occurred in Canada has been over generations of people—generations of human rights and indigenous rights violations; deliberate underfunding of services and programs to indigenous people; forcibly removing children from their families, children being removed and never being seen again by their own families, by their own communities; forced sterilization of women and girls. The list goes on. But from our perspective and from the legal definition, genocide can be over a long period of time of deliberate state action, that looks different from what we commonly think of as genocide. But it’s genocide, legally, nonetheless.

AMY GOODMAN: The report says Canadian police and the criminal justice system have viewed indigenous women through a lens of pervasive racist and sexist stereotypes. The report says police, quote, “apathy often takes the form of stereotyping and victim-blaming, such as when police describe missing loved ones as 'drunks,' 'runaways out partying' or 'prostitutes unworthy of follow-up.'” Declaring this, and with the prime minister of Canada talking about this now as a genocide, as a result of your inquiry, accepting the results of your inquiry, how does this mean the police attitude toward indigenous people will change?

MARION BULLER: Well, first of all, the truth is out there now. It’s public knowledge now that this is how police services have been treating indigenous women and girls. I think that this has started a movement of police services to rethink their policies and practices. But most of all, I’m hoping that it will mean that police services will start to build new relationships with indigenous communities and indigenous people. You can’t unhear the truth now.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’d like to bring in Robyn Bourgeois, an assistant professor in the Centre for Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University. Welcome to Democracy Now! Your reaction to this report? Did you expect such a sweeping and damning condemnation of Canadian government policy?

ROBYN BOURGEOIS: Honestly, I didn’t. Having studied previous encounters like this, where indigenous women have gone to the government of Canada, one of the things I’ve been very critical of is that I found like there was a diminishment of the violence sometimes. And I’ve been waiting, you know, for most of my life to hear what has happened to me, because I am also a survivor of this violence—to hear that be described as genocide. I mean, it’s been 40 years. And I think it’s overwhelming, and it’s about time.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about what you were most surprised by in this report, Professor Bourgeois. Talk about what this means in your community and in indigenous communities across Canada.

ROBYN BOURGEOIS: Sure. I actually think that the most surprising part was genocide. I think we have had a tendency to sort of distance ourselves from that term in some ways. I think about, for example, the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission into Indian residential schools, where the term “cultural genocide” was used. And I’ve always been very critical of that, because that prefix of “cultural” implies that it was our indigenous cultures that were destroyed and eliminated, and not so much our nations and our people. And to say that this is genocide, to actually take this U.N. definition, the standard international understanding of what that means, and say, “No. You know what? What happened to indigenous people, indigenous women and girls and 2SLGBTQQIA folks, in this country is genocide,” is profound. This is a significant moment in Canadian history, where we are having the violence experienced here put on par with other genocidal atrocities that we tend to think of in the world, like the Holocaust or things that happened in Rwanda. And I think that’s really, really significant.

I think—I get a sense from at least the folks that I’ve spoken to in the last day or so, that are indigenous, that this is a really—you know, it’s about time that this has happened. And there’s a kind of a sigh of relief. And, you know, we’ve always known this, and we’ve always argued this. And to hear it reiterated and emphasized and amplified, I think, by the final report is such a remarkable thing. I feel like, in some ways, as a survivor, been carrying that burden and that truth with me, it’s been lifted off my shoulders now, because now there is this official document that backs it up.

And I think this will lead to some significant changes in our communities, because it moves this discussion to a whole 'nother level. There is no longer a place for government officials, for example, like former prime ministers of this country, who said, you know, “This isn't high on our radar,” or “This doesn’t matter,” where it’s, you know, the acts of single perpetrators and not a systemic problem. And now we have this report that says, no, this is absolutely genocidal, systematic violence perpetrated against indigenous peoples in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Bourgeois, you’ve talked about your own experience. You referred to it. What is that experience?

ROBYN BOURGEOIS: Sure. When I was a teenager, in my late teens, in the late 1990s, I was sexually exploited through human trafficking. So, I was lured, in the very early days of the internet, by a man who claimed to want to love me and be my boyfriend, and then very carefully groomed me and then forced me to sell my body in the streets of Vancouver. So, it’s actually a little ironic that I’m having this conversation with you right now from Vancouver, where my story begins. And I was very fortunate, despite being drugged for most of that time and being violently raped and abused, that I was able to escape. And I just felt like I had a second chance, and I was going to do everything in my power to make sure this never happened to another woman.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’d like to ask Chief Commissioner Buller, the comments by Prime Minister Trudeau at the press conference—were you able to have an extended conversation with him? And your sense of how—what your expectations are of the Canadian government moving forward on the conclusions of your report?

MARION BULLER: Well, first of all, Dr. Robyn, can I tell you that I send you my love and my support for your experiences? And you were a wonderful witness with us.

ROBYN BOURGEOIS: Thank you. Thank you.

MARION BULLER: So, I send you my love.

ROBYN BOURGEOIS: Thank you.

MARION BULLER: No, I didn’t have a chance to speak to the prime minister. It was a very busy day yesterday. Really, it’s over to him to make statements, to devise policies, to advance the report forward. In many respects, our work is done, and it’s in the political arena now. I would certainly make myself available should the prime minister want to talk to me and/or the other commissioners about our findings of fact. But when we gave it to—the report to him yesterday, we were, in many, many ways, handing it over to him.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Chief Commissioner, can you talk about the indigenous schools, the residential schools?

MARION BULLER: Yes. We had a slightly different system in Canada than you have in the United States, or had in the United States. In Canada, by law, indigenous kids, mostly what we call the southern part of Canada, but south of our territories, but including parts of our territories, as well, by law, had to go to Indian schools. They couldn’t go to schools where nonindigenous kids were. The purpose of these residential schools was, amongst other things, to take the Indian out of the child. It was to educate them, to teach them white ways, and to destroy the culture, the language and the beliefs that the children brought with them.

As a result of that terrible, terrible legacy, the survivors of residential school live with a variety of horrible, horrible issues—post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction issues, mental health issues. And this is passed on through generations. If the children didn’t go, the parents would be jailed. In many cases, children were hidden in the bush, in the forest, by their parents so that they wouldn’t have to go. And many children never came home.

AMY GOODMAN: Chief Buller, your commission itself has drawn criticism for staff turnover, allegations of lack of transparency and poor follow-up communication with participating family members and the victims. The panel also wasn’t given the authority to have police revisit cold cases. In 2017, family members of victims called the commission to reset, but those calls went unanswered?

MARION BULLER: Well, of course, there’s always criticism when you’re dealing with such a challenging and meaningful topic. But we moved past that very quickly. And I think it’s important to look at our final report and what we were able to do. And I think our final report is brilliant.

AMY GOODMAN: And your final demands of the Canadian government? I mean, you do have the prime minister accepting this report. What do you feel are the most critical recommendations and demands you have made?

MARION BULLER: Well, we don’t say “recommendations”; we say “calls for justice.” And I think—oh, you know, where to start? They’re so interconnected that it’s really hard to say which is the most important. But I think, for a lot of indigenous women and girls, the most important ones are—most important calls for justice will be to be able to drink the water that comes out of the taps in their homes; to have homes that are properly built for the conditions, the environmental conditions; to be able to have a decent life, free of violence; to be able to have their children and to raise their children in the ways that they see fit, that maybe aren’t Western ways, but they’re certainly indigenous ways that have been proven to work for generations. I think, for those women, as well, to be able to have access to proper health services, to be able to live in their own communities regardless of who they marry, to raise their children in their own communities—all of the calls of justice regarding those issues, I think, are going to be the most important to the women who are really suffering right now.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you both very much for being with us, Marion Buller, chief commissioner of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls of Canada, and Robyn Bourgeois, mixed-race Cree academic and activist, assistant professor in the Centre for Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, we look at the deepening divide within the Democratic Party as the 2020 election heats up and calls for President Trump’s impeachment continue. We’ll speak with Ryan Grim, author of the new book We’ve Got People: From Jesse Jackson to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the End of Big Money and the Rise of a Movement. Stay with us.

Media Options