Guests

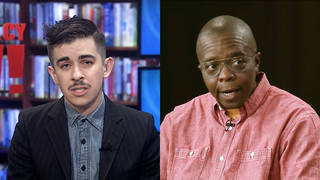

- Sam Federdirector of the documentary Disclosure, which premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival.

- Yance Fordaward-winning director who became the first openly transgender director nominated for an Academy Award for his film Strong Island in 2018.

- Jen Richardsa transgender writer, actress, producer and activist. She is featured in the documentary Disclosure, which premiered Monday at the Sundance Film Festival.

- Chase Strangiodeputy director for transgender justice with the ACLU’s LGBT & HIV Project.

As South Dakota becomes the latest state to pass anti-transgender legislation in the state’s lower house, we look at how trans people have been depicted in film and television over the last century. The film “Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen,” which premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, traces trans representation from the 1914 silent film “A Florida Enchantment” to the Oscar-winning 1999 film “Boys Don’t Cry” to the new hit television series “Pose.” Through in-depth interviews with transgender actors, activists and writers, the documentary reveals the way Hollywood and the media both manufacture and reflect widespread misunderstandings and prejudices against transgender people. The film also champions the transgender people in film and television who have fought and continue to fight tirelessly for accurate and dignified representation on screen. We speak with the film’s director, Sam Feder, as well as actress Jen Richards, Emmy Award-winning director Yance Ford and ACLU lawyer Chase Strangio — all of whom are featured in “Disclosure.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman. This is The War and Peace Report. We’re broadcasting from the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

In South Dakota, the Republican-controlled House passed a bill Wednesday that criminalizes gender-affirming surgery for transgender youth. The bill, which sailed through the House by a two-to-one margin, would make it a felony for doctors to provide anyone under the age of 16 with puberty blockers, hormones and other transition-related healthcare. Medical professionals who provide this care could face up to 10 years in prison. Parents and health professionals say the bill will take away life-saving treatments for transgender youth. This came the same week a South Dakota lawmaker introduced two more anti-trans bills into the Legislature, the latest of more than 25 anti-LGBTQ bills introduced around the country this year.

As this assault on transgender lives takes place in South Dakota and across the country, we turn to a groundbreaking film that just premiered here at the Sundance Film Festival. It’s called Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen. The documentary examines the depiction of transgender people in television and film for more than a century, from the 1914 silent film A Florida Enchantment to the Oscar-winning 1999 film Boys Don’t Cry to the new hit television series Pose. Through in-depth interviews with transgender actors, activists and writers, the documentary reveals the way Hollywood and the media both manufacture and reflect widespread misunderstandings and prejudices against trans people. The film also champions the trans people in film and television who have fought and are fighting tirelessly for accurate and dignified representation on screen.

In this clip from the beginning of Disclosure, we first hear the voice of the legendary transgender actress and activist Laverne Cox.

LAVERNE COX: I never thought I’d live in a world where trans people would be celebrated, on or off the screen.

DANIELA VEGA: Thank you. Thank you so much for this moment.

LAVERNE COX: I never thought the media would stop asking horrible questions —

OPRAH WINFREY: How do you hide your penis?

LAVERNE COX: — and start treating us with respect.

OPRAH WINFREY: You kept it quiet because you said you didn’t want to become othered.

LAVERNE COX: Now look at how far we’ve come.

DELEGATE DANICA ROEM: We have so much more representation in government, in media.

LAVERNE COX: We are everywhere.

ALEXANDRA GREY: And you never know what those positive images do for other people. You never know.

JEN RICHARDS: For the first time trans people are taking center of their own storytelling.

LAVERNE COX: At this point where we’re talking really about unprecedented trans visibility, trans people are being murdered disproportionately still.

TIQ MILAN: That’s the paradox of our representation, is the more we are seen, the more we are violated.

JAMIE CLAYTON: The more positive representation there is, the more confidence the community gains, which then puts us in more danger.

UNIDENTIFIED: I go into the women’s restroom, then I’ve committed a crime. If I go in the men’s restroom, then everybody knows.

ZACKARY DRUCKER: I think all of us in the community have had those moments of being like, “Is this going to somehow alienate people who aren’t ready yet?”

SUSAN STRYKER: Why is it that trans issues have become like a front-and-center issue in the culture wars?

ZACKARY DRUCKER: I think capitalizing on people’s fear is what has landed us in this moment right now, and you have hope on one side and fear on the other.

LAVERNE COX: I think, for a very long time, the ways in which trans people have been represented on screen have suggested that we’re not real, have suggested that we’re mentally ill, that we don’t exist. And yet here I am. Yet here we are. And we’ve always been here.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s trans actress Laverne Cox with a clip from Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen. Well, this week we spoke with the film’s director, Sam Feder, and two of the documentary’s subjects, actress Jen Richards and the award-winning director Yance Ford. They were here in Park City, Utah, for the world premiere of Disclosure. I began by asking director Sam Feder why he decided to take on this subject years ago.

SAM FEDER: OK. Well, first, thank you for having me here. I think maybe the one thing that I’d be more excited about than having a Sundance premiere is being on this show. So thank you very much. I’m thrilled to be here.

So, what made me decide to make this film? You know, in 2014, Laverne Cox was on the cover of Time magazine, and I remember seeing her in this beautiful blue dress, and the headline read “The Transgender Tipping Point.” And there was all this celebration around that. And when I looked off the page, in the real world, that was not the reality. Something really felt amiss with that. You know, trans people are three times more likely to be unemployed than the rest of the population, four times more likely if you’re a trans person of color. We’re witnessing an epidemic of trans women being murdered, particularly black trans women. The suicide rates for trans men are surging. So that’s the reality that I was witnessing and living in. So I was trying to reconcile these two things happening at the same time — right? — the rise of visibility and the rise of social and legislative violence. So I wanted to look at the legacy of those images to understand how we got there and to understand how to use the excitement around positive visibility to work on pushing back against the legislation that’s trying to legislate us out of existence.

AMY GOODMAN: And why did you call the film Disclosure?

SAM FEDER: I think one of the — like, one of the most ubiquitous tropes about us is the need to disclose — right? — that the onus is on us to reveal something about us that is a secret, that no one else knows, that we’re using, you know, to deceive, we’re using to get to something, and that we have something to disclose, as if not everyone has information that doesn’t need to be shared. Jen talks about it really beautifully in the film, how it’s — the idea of disclosure is really prioritizing someone else’s experience over your own. So, that is such a rampant notion in most trans people’s minds and most conversations around trans lives, is the idea of disclosure. And so, just that’s why I wanted to call it that.

AMY GOODMAN: And how does it feel to be premiering this at the Sundance Film Festival, where there are so many Hollywood gatekeepers? If you can describe that and then also give us a sort of a history in a nutshell of representation?

SAM FEDER: I mean, it’s thrilling for me, you know, to be here with all the Hollywood gatekeepers. As a documentarian, like, you get to explore these issues with such nuance and time, as opposed to the actors, who want to get work, you know, and want to speak their truth, but also want to have a career. And so, I am thrilled to be able to be the one to push back and explain how violent these images are. And the fact that they might be heard by the gatekeepers is incredibly exciting. So, that’s the goal.

AMY GOODMAN: The history in a nutshell.

SAM FEDER: The history in a nutshell. What was so amazing about doing this research was finding clips actually from like the 1890s, right? I think the first clip we show in the film is from 1901. And it’s from one of the Edison production houses where he was doing these screen tests. And you see a female impersonator of the time wearing a wig and, you know, kind of just dancing around. I think it’s actually one of the first on-screen kisses — is that how you say it? — first on-screen kiss we see.

And so, I was really taken aback by how this idea of transgressing gender has been a plot device since the beginning of celluloid and how it’s so ingrained in the DNA of film. And you see that sort of imagery of putting a man in a dress as a joke evolve from making fun of women to making fun of gay men to then a stand-in for trans women. There’s this film from the Florida Enchantment — there’s a film called A Florida Enchantment from 1914, and there you start to see how gender transgression and racism have been so also deeply embedded, intertwined together and embedded in our film history.

AMY GOODMAN: And right around that time, Yance Ford, is Birth of a Nation. And you go into this, Sam, in Disclosure, the horrific racist film that was premiered at the White House under President Wilson.

YANCE FORD: Yeah. What’s remarkable is, D.W. Griffith is sort of this embodiment of the beginnings of just sort of massacring the reality of what it means to be black in America, what it means to be trans in America. He takes the vulnerable — the most vulnerable populations, the most vulnerable people, and turns them into devices for his narrative pleasure, you know, to reinforce the predatory black man and then to, on top of that, morph the trans body into something that is an object of ridicule, to be laughed at by us all, but also just to be discarded, to be thrown away.

And, you know, I think that someone, anyone, would have gotten to the first jump cut to advance the story in film. It’s a great editing moment in the history of film. But I also think the fact that we don’t talk about how problematic the images that he created are helps to perpetuate those images. And that’s one of the reasons why I’m so glad that Disclosure exists now, because it really forces people to look. And I think that for so long people have consumed images without thinking about what they’re seeing. And Disclosure really makes you think about what you’re watching, in a way that, in my experience of watching the film for the first time, helps to undo all of those stereotypes and all of that damage, begins to sort of turn back upon itself and turn into something that is potential healing.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, Birth of a Nation became a major recruiting film for the Ku Klux Klan.

YANCE FORD: Oh, yeah. It still is. It still is.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to another clip from Disclosure. This begins with the actress and writer Bianca Leigh.

BIANCA LEIGH: As a trans person, you have the most sensitive radar to tell the difference between you’re laughing with us —

JOHN KELSO: [played by John Cusack] In the phone book, you were listed as F. Deveau.

CHABLIS DEVEAU: [played by Lady Chablis] The F stands for “Frank,” hon. That’s me.

BIANCA LEIGH: — or you’re laughing at us.

TED MOSBY: [played by Josh Radnor] This is the men’s room.

JANET: [played by Amber Stevens West] I know. I’m a dude.

BIANCA LEIGH: Trans jokes? Really?

JACKIE: [played by Bruce A. Young] Hello, Joel. I’m Jackie.

BIANCA LEIGH: Most of us have a good sense of humor. We’ve had to have a good sense of humor.

TRANS CHARACTER: Why am I being arrested?

DET. STAN WOJCIEHOWICZ: [played by Max Gail] I told you. It’s called an unclassified misdemeanor.

BIANCA LEIGH: But we don’t want to be the butt of jokes.

1ST LT. CATHERINE GATES: [played by Ann Sheridan] Oh, wait a minute. I forgot something.

CAPT. HENRI ROCHARD: [played by Cary Grant] What?

1ST LT. CATHERINE GATES: Can you talk like a woman?

CAPT. HENRI ROCHARD:You mean like this?

1ST LT. CATHERINE GATES: That’s awful. Can’t you do better than that?

CAPT. HENRI ROCHARD:No.

JEN RICHARDS: Every trans person carries within themself a history of trans representation just in terms of what they’ve seen themselves.

AGENT DENNIS: [played by David Duchovny] Coop.

AGENT DALE COOPER: [played by Kyle MacLachlan] Dennis?

YOUNGER BEAR: [played by Cal Bellini] Why don’t you live with me, and I’ll be your wife?

JEN RICHARDS: What trans people really need, though, is a sense of a broader history of that representation, so that they can kind of find themselves in it.

AMY GOODMAN: That clip from the new trans life documentary that has just premiered at the Sundance Film Festival called Disclosure. That was actress and writer Jen Richards, one of the stars of the Netflix show Tales of the City and the primetime Emmy-nominated 2016 web series Her Story, which Richards also co-created. Jen, it’s great to have you with us. I’m a real fan of your work. Continue what you’re saying in this clip.

JEN RICHARDS: There is a lack of historical context for trans people, which we actually see in the legislation, as well. There’s this notion that it’s a new phenomenon, that trans people are a sudden trend that need to be combated, because we have this continual historical forgetting. We don’t know our own past. We don’t know that we’ve been around, because we don’t get to see those images.

What Sam’s film really does is situate us today in a historical legacy. I think a lot about one specific idea, just this notion of who gets to play trans people on screen. And I had heard so many times from producers in Hollywood that, “Well, we have to put, you know, this particular star, this man, to play this trans woman, in order to get the film made and push the conversation forward.” And one of the moments that we discuss in the film is that this practice has been going on for over 40 years, and so it’s just this ahistorical reading.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s talk about some of these films. And some of these films, as Sam brings us in Disclosure, were considered groundbreaking, especially around trans life. You had The Crying Game of 1992. You had Boys Don’t Cry of 1999. But talk about what you felt was so critical, why they were such a turning point, but also problematic.

JEN RICHARDS: I mean, The Crying Game is a wonderful example. I love that film. It’s an absolutely beautiful film. There was something incredibly galvanizing and exciting about seeing that character on screen, because it was someone I could identify with. But there’s also a profound —

AMY GOODMAN: And can you, for people who haven’t seen it, in a nutshell?

JEN RICHARDS: Well, I think — are we allowed to spoil Crying Game now? It’s been 20 years. Yes. A character falls for and starts dating this show girl that he sees. And in the moment of her disrobing, as they’re about to have sex, he realizes that she has a penis and is therefore really a man. And his response is to flee to the bathroom and aggressively vomit. And then this trope of men vomiting in response to the disclosure of a trans body has been repeated endlessly, in Ace Ventura, in Family Guy, over and over again. And for trans people ourselves, those images just get placed in our brains and are really hard to dislodge. I’ve dated men for many years, and that image was always running through my mind. Every time I went to disclose to someone that I was trans, that’s the image in my head, is of a man responding. And —

AMY GOODMAN: Vomiting.

JEN RICHARDS: Vomiting, yeah, at the reality of my body, that that’s an appropriate and common response, because that’s the only response I had ever seen was on screen. And so that’s what I am taught. And that’s what the men are taught, that that’s an appropriate reaction. That’s what the whole world is taught is an appropriate reaction, that I’m a legitimate object of disgust. There’s also the fascination with the trans body, and that’s the part that I can at least identify with in a somewhat positive way. There’s a certain glamour and beauty on screen, as well. But it’s always coupled with this violent reaction.

AMY GOODMAN: And Boys Don’t Cry?

JEN RICHARDS: I mean, there’s a similar dual consciousness. I hear this over and over again, from trans men in particular. There’s an excitement and a thrill and a deep sense of identification with seeing a trans character on screen who is operating fully and openly in his masculinity and enjoying his maleness. But then again, it’s coupled with a violent rape and a homicide, a murder. And so, we could never have —

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, that is based on a real story, of Brandon Teena in Nebraska.

JEN RICHARDS: Exactly. We carry those stories with us all the time. That’s what we’re thinking of all the time as we move through the world. And so we have this dual consciousness from these images.

AMY GOODMAN: So, if you could talk about who plays trans people on television and in film?

JEN RICHARDS: One of the biggest issues I’ve had with the way that Hollywood has represented trans people is that it’s very, very common for Hollywood to cast cis men as trans women and cis women as trans men. And in so doing, they’re always reinforcing this notion that at the end of the day the trans person is really the gender that they were assigned at birth rather than who they actually are in the world. And for the most part, it’s a narrative trope. It’s a dramatic device, because the disclosure itself is considered so dramatic, and there’s this notion of deception that always runs through it.

But then there’s this additional layer, that we talk about in the film, where when we lavish awards and attention and praise onto the actors doing this, for this incredible transformational act that they do on screen, we’re also continually seeing those actors in their assigned gender. We’re seeing Jared Leto. We’re seeing Jeffrey Tambor, Eddie Redmayne and Hilary Swank, which, again, reinforces in the minds of the public that a trans person is really, you know, that gender.

AMY GOODMAN: Hilary Swank, of course, for Boys Don’t Cry and Eddie Redmayne for The Danish Girl. Talk about The Danish Girl.

JEN RICHARDS: The Danish Girl, I have very complicated feelings about. I think it’s a really lovely film. I worked with Eddie a little bit, and he’s a wonderful actor. And he took the role very seriously, and I thought he found some really beautiful moments. And the film did open up the idea of trans people to many people who wouldn’t have otherwise known. You know, I know many trans people whose parents love The Danish Girl, and I think that’s who the movie is made for. But again, when we see Eddie being awarded for his performance in that film, we’re still seeing a man in his tuxedo who is getting that award.

AMY GOODMAN: We’ll continue with our conversation on the new documentary Disclosure in 15 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman at Sundance. We continue our conversation about the new film Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen, with actress Jen Richards, Oscar-nominated director Yance Ford, ACLU lawyer Chase Strangio and the film’s director Sam Feder. I asked Sam to talk about depictions of trans men on screen, beginning with the 1999 Oscar-winning film Boys Don’t Cry.

AMY GOODMAN: Sam Feder, take it from there and the films that you show, specifically trans men being portrayed in television and on the silver screen.

SAM FEDER: I mean, we were talking about Boys Don’t Cry. I think what’s problematic with Boys Don’t Cry is that it’s — it a true story, and we need to understand these real stories. It’s just, why is that the story that gets told over and over? Like, what is the fascination with seeing us die? What is the fascination with seeing us get raped and killed again and again? And I’m just really interested in that intersection for a nontrans audience. Like, that’s where we get our audience? That’s the only way we can get an audience, is through pity and victimhood? And so, that’s a real — that’s where I have a lot of difficulty with that film. And I also have a lot of difficulty with the erasure of the black man who was also killed that night in the real story, Phillip DeVine. And so, there is a— and all of the films, actually. There’s a lot to talk about with all of the films, and we try to be really nuanced in our approach to everything.

AMY GOODMAN: You point out that that man is not in the film.

SAM FEDER: He’s not in the film.

AMY GOODMAN: It was — because it’s based on the true story of Brandon Teena.

SAM FEDER: It’s based on the true story.

AMY GOODMAN: But an African-American man was also murdered that night.

SAM FEDER: Three people were murdered that night, and the film only addresses the two white people. And so, that’s — I think that’s — yeah, I don’t have the proper word to say on air for that. But the film —

AMY GOODMAN: Yance Ford, do you have a proper word?

YANCE FORD: This is the internet, right?

AMY GOODMAN: It is not. I mean, it is, but we’re also on television.

YANCE FORD: I mean, it is — again, I loved Boys Don’t Cry. I loved it. But to realize that Phillip DeVine was erased from that story, that his death did not matter enough to the filmmakers to include it in that film, is another act of violence. Right? It is erasing him as if he didn’t matter. But then it is also telling every black trans person, every black gay person, every black ally that your death does not matter, that your presence in this person’s life and your being an ally to that person did not matter.

And I think that one of the things that directors have to do is to be more conscious. Like, I think we have to live in the moment of our creation and understand what we’re doing when we make choices like that. You can’t just wipe someone out of history. He was there, and he’s not here now, just like Brandon Teena. And the more people begin to understand the impact of their decisions creatively, and the more people realize by watching Disclosure that the accumulation of 100 years of these types of choices have on a community, like have on actual human beings, hopefully, for me, that will move people to be smarter, more empathetic and more deliberate about their decision-making, because erasing him is just — I mean, it’s an act of violence, but it’s also just lazy.

AMY GOODMAN: You say in the film, in this very touching moment, among an endless stream of deeply moving moments, “If we can’t see us, we can’t be us.”

YANCE FORD: You know, the wonderful thing about Marian Wright Edelman is that she has such wisdom across the range of human experience. When she said that about children, I don’t think that she would exclude trans children or gender nonconforming children or children who feel like they are nonbinary. She means all of us when she says that. And I think that, again, to have us be homicide victims or to be rape victims or to be exposed in a violent way and then discarded, we don’t need to see any more of that. We see that every day.

AMY GOODMAN: Jen Richards?

JEN RICHARDS: What interests me, that I just realized as we’re talking, that there’s a parallel between The Danish Girl and Boys Don’t Cry, in that both are trans stories that are written and directed and performed by cis people for a cis audience. And in both cases, the complexity of the actual situation is erased in favor of something that’s more easy to package.

In the case of The Danish Girl, Lili Elbe was this incredibly kind of daring, progressive woman, and it was clear that her and her wife were always in a lesbian relationship, because her wife went on to do erotic lesbian painting for the rest of their life. They lived happily as a lesbian couple for many years. And it was only after six surgeries that Lili Elbe eventually did die, because she was always pushing the boundaries of medical science, and that they were operating in this prewar, very artistic kind of queer culture at the time. And so, all that complexity is lost, and instead we have this story of this man who has to become a woman, and then his wife leaves him for this strapping Austrian guy. And so we erase all the actual queerness of it. And again, it reinforces this historical forgetting, as if queer people hadn’t always been around.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to another clip from this remarkable documentary that’s just premiered at Sundance called Disclosure, where Laverne Cox discusses portrayals of trans people in the media. It begins with the comedian Flip Wilson playing that famous character Geraldine on The Flip Wilson Show.

GERALDINE JONES: [played by Flip Wilson] Hit it, maestro! [singing] All of me / Why not take all of me / Can’t you see / I’m no good without you.

LAVERNE COX: What’s interesting for me about growing up in Mobile, Alabama, and then having my first interactions with what it meant to be transgender happening on television is that even when characters weren’t necessarily trans identified, I think those characters affected how I thought of myself as a trans person and how the general public probably thinks about trans people. And one of those early images for me was the character of Geraldine from The Flip Wilson Show.

GERALDINE JONES: [singing] I can’t stop wanting you. Sing the song, Ray!

RAY CHARLES: [singing] It’s useless to say.

LAVERNE COX: I remember I would watch it with my mom and my brother. And my mother loved Geraldine and would laugh at that character, so it was something that existed in the realm of humor. But whenever there was something trans this or sex change that —

MARY CAMPBELL: [played by Cathryn Damon] A sex change operation? A sex change operation?

JODIE DALLAS: [played by Billy Crystal] Right.

MARY CAMPBELL: better sit down.

LAVERNE COX: — I would be very interested, and I would sort of lean in, but very sort of discreetly. These images that don’t seem to comport with like the person that I knew I was. And so, everything that was trans about me, it made me just hate.

AMY GOODMAN: Yet another clip from Disclosure. And that, of course, is Laverne Cox, who is the famous actress, is a trans woman, who is also one of the executive producers of this documentary, Disclosure. Yance Ford, as we go through this history, take it to today, the significance of media representation and whether you think there is hope, whether — where you see it changing in the most important ways and what you want to see.

YANCE FORD: Sure. I am hopeful, because there are so many trans young people who are aspiring filmmakers, directors, writers, actors, who are not asking permission to enter into these professions. They are not asking for anyone’s approval to pursue their dreams. And so, when I see these kids and they ask me about filmmaking or documentary filmmaking, they don’t realize that they are giving me the gift of hope, because I know that after my lifetime these kids will be the ones to reverse this hundred-year history that Disclosure lays out so well and in such an incredible manner for us all to watch. The next hundred years of cinema are going to be written by trans makers, are going to be written by trans actors and writers and directors. And that, for me, is an incredible feeling, to know that another generation of trans kids will not have to ingest the things that I did when I was growing up and then live out the effects of that over the course of their lifetime.

AMY GOODMAN: Sam Feder, you’re the director of Disclosure. You have a remarkable statistic in the film. What is it? Something like 80%?

SAM FEDER: Approximately 80% of Americans say they don’t think they’ve ever met a trans person. They actually probably have; they just don’t know it. And so, that means that everything they know about trans people comes from film and television.

AMY GOODMAN: And that’s why it is so critical, which takes us to Chase Strangio. Chase, you work on legislation all over this country. Right now we’re talking about what’s happening in South Dakota and in states around the country that are introducing anti-trans legislation. And when it doesn’t pass the first time, they do it again. Can you talk about, as you’re featured in the film, as well, Disclosure, the connection between media representations and the laws that are put into place or fought back against all over this country?

CHASE STRANGIO: Yeah, absolutely. And I just think this film is such a critical intervention in every aspect of the ways that power is working to erase, diminish and attack trans people. And I see it all the time. I travel around the country fighting back against legislation. I litigate cases. We were just before the United States Supreme Court arguing against the Trump administration’s position that LGBTQ people, and then trans people in particular, shouldn’t be protected under federal law. And there you could see, even knowing that there were trans people in the courtroom, you had justices, from Justice Gorsuch to Justice Sotomayor, really not being able to imagine trans existence outside those very tropes that we see on film and television. And Judge Gorsuch said something at argument in the Title VII cases in October along the lines of, “Well, wouldn’t it be disruptive to include trans people in society?” And that sense of disruption is him superimposing the images that he’s likely seen from film and television, that this film really does confront us with, and putting that over even the trans people like myself who were sitting there right before him. And we have to do the work of teaching people what they have already been told and then allowing our trans bodies, our trans voices and our trans selves to undo all of that work that has been done against us all these years. And Disclosure is critical in that, in the fight in legislatures, in Congress and before the courts.

AMY GOODMAN: Chase, the film highlights the media’s complicity in and involvement in sensationalizing and diminishing trans people and their stories. There’s an amazing clip with Katie Couric and Oprah Winfrey. Can you talk about the role, how that translates into even the work that you do?

CHASE STRANGIO: Yeah, there’s this idea that the trans person is always something to be laughed at, something to be dissected and explored, something — you know, a person whose body is open to public debate. This idea that we could look at someone and ask them about their genitals and then laugh at them is the very thing that authorizes lawmakers to think that it is in our best interest to constrain the ability for us to survive in our bodies. So, the media’s mocking of us, the media’s insistence that they not teach themselves about how we exist in the world is the very thing that is — it’s really the natural progression into the legislation that we’re seeing. And so, I think we all have a responsibility to tell more accountable stories and contend with our bodies in ways that treat us with just basic human dignity.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to end with Jen Richards and your work as a writer, as an actress, where you see the rays of hope are right now, in the kind of work that you’re doing and that you’re seeing other people doing, the openings. And would you consider it a victory if people didn’t even say “trans actress”?

JEN RICHARDS: I love that we’re focusing on that, as well, because that’s an important pairing with the critique, is to applaud the things that are done well. And you’re a fan of Tales of the City, and I think that’s a really wonderful contemporary example of a show that had trans directors, trans writers, trans consultants, trans actors. And what we then see is a really complicated, nuanced portrayal of trans lives and in diverse kinds of trans lives. I think a lot about a email I got from a mom, who had to tell me that she watched her trans daughter sit on the floor and watch my episode of Tales of the City three times in row, back to back. And I think about what impact that will have on that child, that they get to see that and that that’s the image and those are the kinds of stories that will carry her forward into her life. So, I’m thrilled that those kinds of things are beginning to happen more and more frequently. And it’s because of conversations like we’ve been having behind the scenes over the last decade and will now be brought forward into the public through Sam’s film.

AMY GOODMAN: Actress Jen Richards, Oscar-nominated director Yance Ford, ACLU lawyer Chase Strangio and Sam Feder, the director of Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen.

That does it for our show. I’m speaking today at 2 p.m. at the Park City Museum on Main Street.

Special thanks to our crew here at Park City TV: Danielle Turner, Parker Martin, Diego Romo, Jaclyn Daly, and Yurivia and Ethan Barrios. And our amazing Democracy Now! crew here in Utah and in New York. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us from Park City, Utah.

Media Options