Guests

- Lawrence Wrightauthor, screenwriter, playwright and a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine.

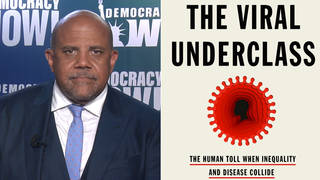

A global pandemic that “brings the world to its knees.” We’re facing that today, but this is a description of the novel, “The End of October,” which came out in April 2020 to a world under lockdown, as COVID-19 tore across the globe. It was written and conceived of far before the coronavirus was first discovered, and we speak with its author, Lawrence Wright, who notes the book is based on countless interviews with scientists and public health experts that saw this pandemic coming, and describes how the story follows a high-level CDC official in his efforts to contain and cure a deadly virus. The novel has since been called “eerily prescient” and “a warning after its time.” Wright is a New Yorker staff writer.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

A global pandemic that “brings the world to its knees.” Yes, that’s what we’re facing today, but that’s actually the story of a novel called The End of October that came out in April, so, of course, was written well before. It came out in April to a world under lockdown as COVID-19 tore across the globe, written and conceived of far before the pandemic and the coronavirus was first discovered.

The book is based on countless interviews with scientists and public health officials that saw this pandemic coming. The story follows a high-level CDC official in his efforts to contain and cure a deadly virus. The novel has since been called “eerily prescient” and “a warning after its time.”

For more, we’re joined by its author, Lawrence Wright. He’s joining us from Austin, Texas, New Yorker staff writer, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Lawrence. It’s great to have you with us.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: So, President Trump famously said no one could have predicted this. So, how is it that your book comes out right at the beginning of the pandemic? Where did you get this idea? And tell us the story.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Well, I’ve always been interested in public health. As a young reporter, I did a number of stories about epidemics. And I just found the people that were involved in that field of medicine so noble, really. You know, they’re ingenious. They’re courageous. They go to these hot spots around the world that I wouldn’t want to get close to. And when I was thinking about the subject of, you know, what could end civilization — that was the premise — I thought, you know, a nuclear war, but a pandemic. I think that’s the thing that — you know, there is a world full of heroes in there, and it’d be easy to write about one of them. And so that’s where the idea generated.

As for being prescient, Amy, it was just research. You know, there were playbooks. There were tabletop exercises. And there were all these public health experts who have been expecting something exactly like this. So, you know, the fact that there are these eerie coincidences between what I wrote in the novel and what happened in real life is simply a matter of following the pattern that was already laid out. Everybody that I talked to knew something like this could happen. So the idea that nobody saw this coming is a total fiction.

AMY GOODMAN: So, tell us the story.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: OK. This is — you know, my hero is named Dr. Henry Parsons, and he’s actually named after a British epidemiologist in the 19th century who proved that influenza was actually contagious and not spread by environmental gases. And he’s well known in his field.

He goes to a conference at World Health headquarters in Geneva, and there’s a report about an outbreak in a detention camp in Indonesia. And he’s suspicious of it. He goes, and it’s exactly what he feared would happen one day. It’s a novel influenza virus. It’s never been seen before. There’s no treatment for it. And he worries right away that it’s going to become a pandemic. It has to be contained.

But, unfortunately, one of his — his driver goes on Hajj to Saudi Arabia, and 3 million pilgrims are crowded closely together there. And that’s the ignition point. And that’s something I had worried about when I was in Saudi Arabia and working on, you know, my book about al-Qaeda. These mass gatherings are so dangerous for public health. It’s not just Islam, but, you know, the rock concerts and things like that. When people crowd together like that, it’s so — it’s perilous, from a public health point of view.

So, that’s where it takes off from. And, you know, what happens in America is exactly what I read about in those playbooks and in the instruction manuals that public health officials gave me.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Lawrence, you said that your novel was inspired in part by Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic novel The Road.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Yeah.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: You’ve also said that reading the news now, you feel like you’re reading another chapter of your book. But, of course, the worst consequences of the pandemic that you depict in the book have not yet come to pass across the world in the midst of this pandemic. Do you expect worse to come?

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: I think that it’s possible, in two ways. One is that this pandemic is voracious, and it won’t stop until, you know, we have herd immunity. And I don’t think that, honestly, Americans are going to take the vaccine in sufficient numbers. So I think the vaccine — so, the influenza will continue — excuse me, the virus is going to continue to spread until it’s exhausted itself.

The other thing that I worry about, honestly, is I think this is just a harbinger. You know, this is just the latest brand-new virus. Since the turn of the decade, we’ve had Ebola and Nipah and Zika and SARS-1 and now this. You know, the pace of these new diseases is picking up. And our ability to counter them is pretty clearly not so great. And, you know, when you compare it to the 1918 flu, for instance, there’s very little difference, in a hundred years, in our ability to deal with a brand-new virus.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Lawrence, you mentioned the question of vaccines and the fact that Americans, a lot of Americans, won’t take it. In fact, less than half of Americans have said that they would take a coronavirus vaccine once it becomes available. Now, you, yourself, had an adverse reaction to a tetanus vaccine when you were a child. Could you explain why you think that taking a vaccine for this virus, whenever it becomes available, that — first of all, that you would take it, and why you think it’s important that everyone does, everyone who gets access to it, that is?

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Yeah, it’s true that I — when I was a child, I woke up one morning — I had had a tetanus shot — and I couldn’t get out of bed. I was paralyzed from the waist down. And I recovered. But, you know — and to this day, I’m not sure if it was Guillain-Barré syndrome, which is, you know, rare but still sometimes happens after inoculations. And some people get it from eating shellfish. Most people recover, but some don’t. It’s a very dangerous disease. And then, you know, it could also have been the horse serum in which the vaccine was grown, and I might have been allergic to that. But in any case, it was a severe reaction and quite terrifying. So I have an interest in making sure that this virus — that this vaccine is safe.

And so, I spent a lot of time talking to — in my novel, I researched it by going to the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, which is Dr. Fauci’s shop, and talking to Barney Graham, who is the chief designer of the vaccines there. And also I spoke to Philip Dormitzer at Pfizer. These guys are the ones who did design the number one and number two vaccines that will be coming online sometime late this fall. And they helped me design the novel — the virus in my novel and helped me cure it. So, I had, you know, access to some of the greatest experts in the world.

But in learning about the making of the vaccine, I was reassured. For one thing, you know, it’s not grown in an animal medium. It’s not grown in eggs or in horse serum as so many vaccines are. What it is, essentially, is a mutated form of the virus that cannot propagate itself, but it does alert the body’s immune system. So, I don’t see any reason my body would find an allergic reaction to it. I don’t see any reason why it might stimulate something like a Guillain-Barré syndrome. So I feel at ease.

And also, you know, there’s a — I think the reason that we have so little confidence in the vaccine is that the mixed messages that have come from the government have confounded people. I mean, as you point out, about half of Americans now say they would not take the vaccine, but it was three-quarters in May who would. So this confidence level is plummeting. And there’s a reason for it. It’s because the government itself is untrustworthy.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, talk about this. You have, every time President Trump says a vaccine by — not particularly a date, but using the word Election Day, immediately puts it in a political context.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Well, you know, that’s why everybody’s concerned. I mean, even calling it Warp Speed makes people jittery, because I think everybody understands that there are risks associated with vaccines. And there are certainly risks in not taking vaccines. That’s the one that we’re all exposed to right now. So, it’s always a balancing thing.

But there’s also a sense of service to your community. It’s not just to protect you. It’s to protect our community and allow us to get back to normal life. So, you know, that is also fraying, those social bonds that in the past we didn’t think about in the same way we do now.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s interesting that, as we speak, a Cornell University study, that just came out, of millions of English-language articles points to President Trump as the biggest surprise — that Trump, president of the United States, was the single largest driver of misinformation around COVID. Lawrence Wright, in your book, The End of October, you choose a flu to be the source of this pandemic. Can you talk about why — and, of course, that ended up being what it was — and your research back to 1918, the so-called Spanish flu?

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Yeah, you know, flu is the thing that public health people fear the most. And 1918 is in their minds. It is the — you know, a hundred years ago, it was probably the greatest plague to hit humanity ever, in terms of the concentration of death over a short period of time. And it was — really, even today, October 1918 is still the most deadly month in American history. About 670,000 Americans died during the 1918 flu.

And yet, one of the really intriguing things about it, essentially, it was buried in public consciousness. It was overshadowed by World War I, which killed far fewer people than did the flu, and even far fewer American soldiers. I mean, 1918 killed more Americans than all the American soldiers in all the wars in the 20th century. So, you know, to have put that aside in our memory is so odd to me. And when I was writing about an outbreak of H1N1 influenza in 1976, which is the same strain, I was shocked that I had never heard of the 1918 flu, and then even more shocked to find out that my father, when he was a child, had it. So did his parents. The graveyards, everywhere you go, there’s a line, you know, of — 1918 is one of those dates that is etched into graveyards all over the world.

And so, it intrigued me that there was this catastrophe that essentially had been buried, and in literal and figurative senses. So, that is one of the things that drew me to the idea of bringing back the idea of an influenza, something that we think we can live with. But the truth is, a brand-new influenza, like what we had in 1918, could be far more devastating than the coronavirus that we’re living through right now.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Lawrence Wright, let’s go back to that, I mean, the American response to this pandemic. And, I mean, as you’ve just pointed out, the Spanish flu killed more Americans than all the wars of the 20th century. The hero in your book is an official from the CDC, an agency that you’ve covered extensively and for which you’ve had a great deal of admiration. And the agency is not just important for the U.S., but in fact for the whole world, that looks to the CDC often for health guidance. So, could you talk about, I mean, your assessment of how this agency has responded to this pandemic, and the work of the agency, in particular, under this administration, under the Trump administration, and how that may have complicated the American response?

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Well, when I was a young reporter, the CDC was an independent agency. You know, when the CDC spoke, everybody, you know, marched to that tune. And it was unparalleled in its standing in the world. I mean, there are CDCs all over the world. They’re all built on the model that we created in the United States. And it’s been heartbreaking to see how that proud agency has stumbled so badly and how politicized it has become. It’s become a captive agency of the Trump administration.

The worst thing, I think, that’s happened with the CDC is the test. Right in early January, as soon as they got the sequence from China, they got to work on making a vaccine test for the new virus. And they did it in record time. They sent it out to, you know, different hospitals around the country. But it turned out to be flawed. And, you know, they sent it — for instance, the New York Health Department tested it against distilled water, and it turned out to show a positive reaction. So, it was giving out too many false positives to be reliable. And so they suspended testing, and they were going to go back and fix it. Meantime, the FDA wasn’t going to let anybody else make a test, and so we had to wait for the CDC to remedy its error. We lost three weeks during that period of time, that we never got back. The virus was seeded all over America. We were totally blind to the spread. And unfortunately, by the time we finally did get a test, it was very limited. It took, you know, sometimes — like in the case of my daughter, who was pregnant, it took her 18 days to get the results back. At what point does that become useful? You know, the bottleneck that was created by the failure of the CDC to make a reliable test is one of the reasons that we never, never caught up and we never got to a baseline that we could control.

So, that’s where we are now. It’s raging out of control. There still aren’t enough tests. They still are not reliable enough to get back. And now many due tests are coming online. But we will never recapture those crucial three weeks when the CDC failed in making a test that would be reliable.

AMY GOODMAN: As we talk about the science, Lawrence Wright, this issue of the poverty and what this means for a whole breakdown of society is one of the focuses of your novel, The End of October. We’re talking to you when the World Bank comes out with a report that says the rise of poverty in East Asian and Pacific nations, for the first time in two decades, as many as 38 million additional people falling below the poverty line, particularly when we’re looking at the Global South, but also at the people in this country, who least have access to wealth. You talk about the closing down of banks, militias going through the streets, no ATMs open, that scenario. Expand on that.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Well, there are things that I miscalculated in the novel. And one was, you know, the food supply we’ve been able to hang onto. And that’s a lifeline. Think about the chaos if that broke down. But, you know, the militias and those kinds of things, I just anticipated, because I — what I did, honestly, is look at the stresses that we already have in our society, and upped the pressure. And that is the role of the virus. You know, when you add stress to a system that’s already fractured, then you can imagine what might happen. And so the novel is very dire in that regard.

But, you know, it does concern me that I see things trending in that direction. If we can keep the food supply, if we can keep the money supply in operation, I think the nation will climb out of this. But it’s pretty clear that we’ve been set back enormously, especially in the progress of people who are in the lower tier of income. You know, they were just beginning to have increases in their wages. They were just beginning to make a step forward, out of the decades-long frozen place where income and wealth in the lower part of American workers has been held. It was at that point that the virus came along and has — you know, who knows how many decades we’ve been set back by this terrible economic collapse?

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Lawrence Wright, before we conclude, I’d just like to ask you about what surprised you in the way in which people have responded to this pandemic, as against what you imagined in your book. I’ll just read a brief excerpt from The Atlantic. Sophie Gilbert writes, quote, “For everything that Wright seems to have anticipated, he gets one thing strikingly, consolingly wrong. Human nature, in the novel, is inherently savage.” She goes on to say, but “Most people have shown themselves to be far better than The End of October imagined” — that is, far better in this pandemic. So, your your response to that?

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: I think that I underestimated the willingness of people to isolate themselves voluntarily for long periods of time, at great personal cost, financial cost, emotional, spiritual, all those reasons. You know, of course, my virus in the novel is far more mortal than the one that we’re dealing with, and so the consequences are greater. And the food supply breaks down. There are other stresses.

But you can see that sense of community breaking down now, you know, the fraying, the exhaustion of people from being confined for so long, for being out of work. Those kinds of things are taking a toll now. And I fear that some of the trends that I pointed at in the novel will become increasingly apparent, and that’s a great concern to me. And it’s all the more reason for people to be ready and receptive and willing to take the vaccine when it finally appears.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, Lawrence Wright, since you are so prescient about things, writing about a pandemic before it actually happens, tell us what your wife wants your next novel to be about.

LAWRENCE WRIGHT: Well, I’ve gotten a lot of suggestions, and, you know, a novel about the first woman president is one of them. A novel about how we solved climate change. I’m getting, you know, plenty of — if you got any suggestions, I’m open to them.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, thanks so much, Lawrence Wright, author of the new novel, published in April, titled The End of October. He’s a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, a screenwriter, a playwright and staff writer for The New Yorker magazine.

To see Part 1 of our discussion with him — he’s also executive producer of a new Showtime film that’s called the Kingdom of Silence, and that is airing on Showtime beginning October 2nd, that’s the second anniversary of the murder of The Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi — I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh — go to democracynow.org for more. Thank you.

Media Options