Guests

- Mará Rose Williamseducation writer at The Kansas City Star who led the effort to examine the newspaper’s coverage of the Black community.

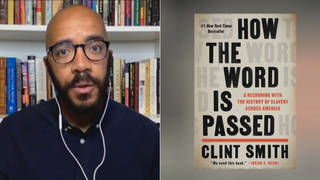

- Mike Fanninpresident and editor of The Kansas City Star.

In a historic step, The Kansas City Star, one of the most influential newspapers in the Midwest, has apologized for the paper’s racist history. The paper’s top editor, Mike Fannin, admitted the Star and a sister paper had reinforced segregation, Jim Crow laws and redlining, and “robbed an entire community of opportunity, dignity, justice and recognition” with its biased coverage over many decades. We speak with Fannin and Mará Rose Williams, a longtime education writer at the paper who led the effort to examine the newspaper’s coverage of the Black community following the police killing of George Floyd and the nationwide racial justice uprising this year. “Mainstream newspapers across the country, not just The Kansas City Star, have not done a good job of covering the Black community,” says Williams.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

The Kansas City Star, one of the most influential newspapers in the Midwest, has apologized for the paper’s 140-year racist history. The apology appeared in a recent article titled “The truth in Black and white.” It began with these words: “Today we are telling the story of a powerful local business that has done wrong.

“For 140 years, it has been one of the most influential forces in shaping Kansas City and the region. And yet for much of its early history — through sins of both commission and omission — it disenfranchised, ignored and scorned generations of Black Kansas Citians. It reinforced Jim Crow laws and redlining. Decade after early decade it robbed an entire community of opportunity, dignity, justice and recognition.

“That business is The Kansas City Star.”

Those are the opening lines of an apology from The Kansas City Star. In a series of articles, the newspaper details how it largely ignored civil rights protests and the illegal segregation of schools in Kansas City decades after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. During the civil rights era, the Star's editor at the time reportedly said, quote, “We don't need stories about these people.”

In 1968, five Black men and a Black teenager died in Kansas City during unrest following the assassination of Martin Luther King. At least four, and possibly all of them, were killed by police, but the paper failed to follow up on the killings or call for anyone to be held accountable.

The Star also ignored the cultural significance of African American icons, including jazz legend Charlie Parker, who was born in Kansas City. Parker’s first significant headline in the Star appeared after he died, but the paper misspelled his name and got his age wrong.

We’re joined right now by Kansas City Star editor Mike Fannin and Mará Rose Williams, an African American journalist who writes about education at the paper. She led the effort to examine the newspaper’s coverage of the Black community.

We’re going to begin with Mará Rose Williams. Talk about your research and what you took to the editor, who we will also speak with, to say, “We’ve got to do our own reckoning here.”

MARÁ ROSE WILLIAMS: Good morning, Amy.

Yeah, it was the summer of 2020. And we all know what was happening at that time. And I felt like the time was right. I mean, we all know — I know, I’ve known for years — that newspapers, mainstream newspapers, across the country, not just The Kansas City Star, have not done a good job of covering the Black community. They either ignored it, covered it inadequately or inaccurately. And I knew this.

But it’s one thing to be able to say to a community, “We’re sorry for that,” but I thought it was important that we be able to show them what we were apologizing for. So, with the timing that I was in, you know, after the death of George Floyd and the protests that were happening all around the country, I went to my editors, and I suggested to them that we make a public apology, and not only that, that we go back and we find those places, examples, of where we fell down as a media organization, and show the public what that looked like, what that sounded like, so that they could see. I mean, you could tell someone about ugliness over and over again. That’s one thing. But it’s another thing to show them what that looks like, what that sounds like. And that’s what I hoped to do.

And they did not blink. They picked it up and then said, “Yes, let’s do this.” And once colleagues, other colleagues, heard about this, they were eager also to get involved. And we jumped in and began to research.

Now, what we had to do was to find the stories we wanted to tell. We actually started with a task force of Black community members and talked to them about what it was we wanted to do. And we wanted to hear from them their perception of The Kansas City Star over the years and how they — the kind of job they thought we might be doing. And so we spent some time talking with them first, and then came up with or pinpointed several particular stories that we wanted to look at, areas we wanted to look at.

We began with — because it didn’t exist, right? It wasn’t in the Star. We hadn’t covered these things well. We went to the Black press, the Kansas City Call, which is a weekly Black newspaper in Kansas City, and started looking there to see how they had covered certain areas — politics, education, civil rights, entertainment and so forth — and then compared that with what was done in The Kansas City Star, and then began to do a series of — a lot of research. We spent a lot of time going through court documents, going through archives in the Historical Society, reading book after book about racism in Kansas City and race in Kansas City, to actually substantiate various areas that we wanted to cover. So, I mean, that’s how it started.

AMY GOODMAN: And —

MARÁ ROSE WILLIAMS: That’s how — go ahead. I’m sorry.

AMY GOODMAN: And I’d like to go to Mike Fannin then. If you could pick it up from there? You have your education editor, Mará Rose Williams, coming to you. You’re the editor and president of The Kansas City Star, extremely influential in the Midwest as you cover all issues, but particularly Kansas City, which spans two states, Missouri and Kansas. Respond to what — talk about when she came to you, your response, and what this apology means to you.

MIKE FANNIN: Sure. Well, as Mará said, and Mará and the whole team — and I think she made a great point here, which is, you know, we were really speaking for a number of people at the Star, a number of people who were excited to be on this team. When they came to us with this idea, the answer was easy. It was an absolute yes.

The execution, I think, was difficult, because, as I wrote about in the column, I think that as reporters really dug in and unearthed a lot of these very human examples that really brought home how this systematic problem in our coverage had revealed itself in stories we told and stories we didn’t tell, it was difficult to reconcile that with the sort of place that we’ve come to love and appreciate.

But we also understood that those frameworks, those historical frameworks for coverage, are difficult to tear down. And even though I think the Star has probably spent the last 40 years trying to tear them down — and had success in certain areas — and spent a good deal of time writing about institutional racism in agencies in Kansas City, like the fire department or the police department, we had never really turned that investigative power, that power of self-examination, on ourselves. We had never really turned our — you know, put ourselves under the microscope.

And why I think it’s important, what it means to me, is — Mará and I have been doing shows for about a week and half now, and I’ve had a lot of time to sort of think about the reaction that we’re getting, and I think that my concern was that — my only concern was, you know, sometimes when you’re telling a historical story, you can lose the audience. Not everyone has the kind of interest in history that we do. But clearly, from the reaction that we’ve gotten, in Kansas City and across the country, in comments that have come in via email and phone calls and requests for us to do programs, and not just this kind of programming, but programming with other news outlets, it tells me that this is a story that still resonates today in Kansas City, and it resonates across America.

And here’s why. There is still so much mistrust in these communities we’ve underserved. And we, as truth tellers, should be willing to humble ourselves and reignite those conversations with a simple “I’m sorry.”

AMY GOODMAN: I’d like to turn to a clip from a video that The Kansas City Star produced as part of its report, featuring an interview with Mickey Sutherlin, whose father, Leroy Adams, died in the 1977 flood in Kansas City.

MICKEY SUTHERLIN: The Star wrote about the death toll. They ran three or four articles about my father. They did that with the people that died, not the people that suffered. Mostly, the Star and Times and the local TV news networks, they focused on the damage that was done to the plaza area and stuff and the businesses that were destroyed, not a lot about the residential neighborhoods. And those were Black neighborhoods.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Mará Rose Williams, the flood and what you really have described as the racist coverage by The Kansas City Star, explain.

MARÁ ROSE WILLIAMS: Yeah, I mean, when you look back — when I looked back and I was reading about the flood, I had heard from people I interviewed that their stories were not told. And when I began to do some research, I was able to find that, you know, for example, they would talk about the structural damages to homes in the suburbs. We talked about how water flowed into people’s homes in the suburb and washed all of their contents away and left them with nothing. But then, when we talked to — when we mentioned anything that had to do with the Black community, we would just say something like, “There were homes damaged in that area.” We never talked to the people who suffered. We never told their real story about what the loss meant to them and how devastating it was for them.

And so our readers did not get a chance to see the other members of their community, the members of the Black community, and that they, too, had suffered, and the damage that was done to their homes. These people felt invisible, because their story was not being told, as Mr. Sutherlin was saying. It was as if they didn’t exist. And so, I found that very painful as I read that. And that was seen in story after story for decade after decade, just this invisibility, as Mike’s apology said, that we did nothing or little to change the narrative, the perception about who Black Americans, Black Kansas Citians were.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we will link to your whole series at democracynow.org. Mará Rose Williams, education writer at The Kansas City Star, Mike Fannin, president and editor of The Kansas City Star, which recently published an apology for the paper’s racist history, titled “The truth in Black and white: An apology from The Kansas City Star.”

And that does it for our show. Democracy Now! produced with Renée Feltz, Mike Burke, Deena Guzder, Libby Rainey, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Carla Wills and Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud and Adriano Contreras. Our general manager, Julie Crosby. Special thanks to Becca Staley, Miriam Barnard, Paul Powell, Mike DiFilippo, Miguel Nogueira, Denis Moynihan.

Media Options