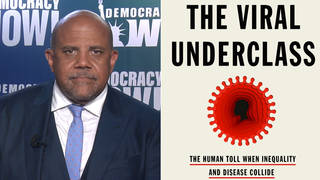

As health experts warn the coronavirus is on the rise in 41 states, many governors are reimposing restrictions after attempts at opening up the economy, but President Trump wants schools open. We speak with public health historian John Barry, who warns “The Pandemic Could Get Much, Much Worse” if we don’t take bolder action now. Barry is a professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and author of “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. As the coronavirus is on the rise in 41 states, the U.S. reported a record number of daily new cases Tuesday, with Wednesday’s count just barely below, at more than 67,000 new cases. The official U.S. death toll is over 137,000. Hospital beds are running low in Texas and Arizona.

As several other states face increasingly dire circumstances, many governors are reimposing lockdowns after attempts at opening up the economy. Earlier this week, California Governor Gavin Newsom ordered the closure of indoor restaurants, movie theaters and other institutions. Alabama and Montana have ordered all people in public to wear masks.

This comes as Oklahoma Republican Governor Kevin Stitt has become the first governor to test positive for the virus. He attended Trump’s indoor Tulsa rally on June 20th and did not wear a mask. Herman Cain, the African American 70-year-old former presidential candidate, also attended the rally without a mask — he’s a Trump supporter — and has been hospitalized ever since with COVID.

Well, we turn now to a guest who warns the pandemic could get much, much worse if we don’t take bolder action now. Professor John Barry is professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and the author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. In recent New York Times op-ed, he argues a comprehensive shutdown may be required in much of the country in order to regain control of the pandemic.

Professor Barry, welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us from New Orleans. If you can start off by saying — talking about why you believe this pandemic can get much, much worse, and what that bold action you think the country needs to take to turn it around? The United States, the wealthiest country in the world, has a quarter of the deaths and more than a quarter of the infections in the world, even though it has less than 5% of the population of the world. Professor Barry?

JOHN BARRY: Right. Well, real problem will come later, when — in fact, Redfield, the CDC director, said much the same thing a couple of days ago. There had been hope that hot weather would limit spread of the virus. Most respiratory viruses, and probably this one, as well, do transmit less well in hot weather. Obviously, we are seeing explosive spread in much of the country right now. And unfortunately, there’s every reason to believe that the spread will actually get worse when the weather turns colder and it forces people indoors into poorly ventilated spaces. You know, that’s standard for almost every respiratory infection, from influenza to the common cold. You know, right now, obviously, we’re not in a good place.

I think when you compare where we are to Europe, it gives you a real sense of how bad things are here. You know, Italy was a place that seemed totally devastated by coronavirus first. Right now they have, on average, about 200 new cases a day in the entire country, yet their population is roughly equivalent to Texas, Florida, Arizona, Georgia combined. And if you add the cases up in all of those states, you’re talking about probably close to — you know, well over 30,000 — 35,000 cases compared to fewer than 200.

And what that demonstrates is that the public health measures that are being advocated, unanimously, by every person in public health, that’s what Italy did. And they got the cases in the entire country down to 200 a day. If we had done that the first time around, if we had brought our baseline down to a level like that, then we wouldn’t be having a debate over opening schools. We wouldn’t have a debate over playing football. Those things would be automatically going forward with precautions. And the economy would be operating at practically 100% by now.

We failed to do that initially. The baseline — you know, we did blunt the curve, sort of flatten it, but we did not bring it down. So that baseline remained too high. And when we reopened too soon in many states with that baseline already high, it just took off. You know, we’re pretty close to being too late, but we’re not too late at this point to bring the thing under control. And if we don’t, again, when the weather gets cold and people are inside, it could be pretty devastating. It’s already devastating.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Professor Barry, the countries — Italy, of course, which you mentioned, was initially the epicenter of the pandemic. Now, what these countries have done, not just in Europe, but also in Asia, in addition to massively expanding testing, is also using contact tracing.

JOHN BARRY: Right.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But that’s scarcely been used in the U.S. I mean, you point out in a recent article that even where it has been attempted, in Miami, for people who tested positive for COVID, only 17% of those people completed the questionnaires that would be required for carrying out contact tracing. So, could you explain why you think this hasn’t been one of the principal strategies that the U.S. has followed, despite the successes that this strategy has resulted in elsewhere, and also whether it’s even possible for contact tracing to work in a country with such enormous numbers of infections?

JOHN BARRY: Right. Well, it has been a strategy, but the strategy has not been executed. Again, it goes back to the investment in resources, how seriously people take the disease. Obviously, we’ve gotten no leadership out of Washington. A few states have done a pretty good job on contact tracing. Too many states have not.

And again, when the case count is pretty low, it’s pretty easy to contact trace. When the case count is over 10,000 in a single state every day, no, that’s not possible. Public health experts have recommended somewhere between — some as low as 100,000 contact traces nationally. Others have thought as many as 300,000 were needed. But the actual number that was employed, the best number that I could find was about 27,000 — obviously, way below the minimum estimate, much less the higher estimates of what’s needed. It’s just a question of resources and seriousness. And we haven’t had that.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Professor Barry, so even though the U.S. leads by far in the number of infections with respect to countries — I mean, in an individual country — the vast majority of increases now are occurring in the developing world. Indian epidemiologists, in fact, believe that India’s case numbers will very soon eclipse the United States. Now, you’ve pointed out — you’ve written, of course, an entire book on the Spanish flu. You’ve said that most people — more people died in the developing world then because people in the West had been exposed to other influenza viruses, so already had some protection against the Spanish flu when it emerged. Now, how much do we know about whether exposure to other viruses is a factor here, as well, in COVID-19, in determining or influencing mortality rates?

JOHN BARRY: Well, there is some slight indication that there may be some very, very small cross-protection from other coronaviruses, but that wouldn’t be major. And those things probably have been worldwide. Influenza was a little bit different. You know, most of the developed world, people have probably seen multiple influenza viruses. The 1918 virus was a new virus. But you still got, compared to — you still got some cross-protection if you had been exposed to other influenza viruses. In so-called virgin populations — and this isn’t true only of influenza, but of most viruses — when people hadn’t seen any influenza virus, their immune systems were completely naive. Then you were getting instances where 20%, sometimes higher than that, of the entire population was being killed. You know, that’s not really the case here. This virus is quite different. You know, again, the common cold is pretty general around the world, those coronaviruses. I don’t think that there’s indications of a lot of benefit from them.

AMY GOODMAN: John Barry, I wanted to stay on this issue of the Spanish flu. You wrote the book The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. And I was wondering, as a historian, if you can give a history lesson about what happened there. And specifically, I mean, we’re calling it, of course, the Spanish flu, but I am wondering — you write, the single most important lesson from the 1918 influenza was to tell the truth. The Trump administration is doing exactly the opposite. I hardly learned about the Spanish flu, and certainly learned about World War I in school, but not the Spanish flu of 1918. And I wonder if that was linked to actually a censoring of this story, and if we could see something similar to people trying to speak out about what’s happening right now in this country as President Trump tries to tamp down that discussion and move on. Go back to 1918, why it was even called the Spanish flu, not having anything to do with Spain, where it came from, and how it’s linked to war.

JOHN BARRY: Well, of course, most of Europe and North — U.S. and Canada were at war. And in the warring countries, there was either censorship or, in the U.S., pretty effective self-censorship. Spain was not at war. We’re not sure where that 1918 virus entered the human population. It could actually have been in the United States, could have been China, could have been France, could have been Vietnam. But it didn’t start in Spain. It was well established before it got to Spain. But because Spain was not at war, their press wrote about it. In the warring countries, the powers that be didn’t want any bad news — any bad news, about anything — to get out, because they felt it would hurt morale and hurt the war effort. So, Spain was writing about it. The Spanish king got sick. Celebrity culture, then as now, got a lot of attention, and it became known as Spanish flu.

In the United States, there was no Tony Fauci. Even national public health leaders were saying this is ordinary influenza by another name, for the reasons they were trying to maintain morale. But nobody was calling it a hoax in 1918. The virus was much more lethal than what we’re facing now. If you see your neighbor die 24 hours after their first symptom, you know perfectly well it’s not a hoax. All that happened as a result of this, the lying that was going on, was that people lost all trust. It spread fear — terror, in some cases. And in the worst places, society actually began to fray. And people died who otherwise would have survived if they had been told the truth, if they had been able to recognize early on, from the very beginning, how serious it was, and take some measures to protect yourself — themselves.

And those measures are exactly what people recommend today: social distancing, mask wearing, wash your hands — exactly the same things. We know that they are effective. You know, as I was saying earlier, Italy got its cases down to 200 a day; Germany, roughly 400 a day, in country significantly larger than Italy. Most of Europe has the disease well under control at this point. And, of course, in Asia, the numbers are even smaller. Vietnam, which shares a border with China, hasn’t recorded a single death. Not one. So, public health measures work. But you have to do them. We have not done them in the United States, or too many people have not done them in the United States.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Professor Barry, meanwhile, here, in Florida, one of the states where cases are rising, one in three children — that is, 31%, almost one in three children — have tested positive now in Florida, and health officials are concerned that there might actually — it’s too early to tell. We can’t say with any degree of certainty that children will not be affected long-term by getting the virus.

JOHN BARRY: Right.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But I want to go to another — you made the case, in March, that there was no indication that COVID-19 will become more virulent than it is now.

JOHN BARRY: Right.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But you did say that it’s going to come in several waves and become endemic. Is there still — I mean, that was three-and-a-half months ago, when it first began, it spread here. Is it still the case, does the latest research still confirm, that COVID-19 won’t become more virulent?

JOHN BARRY: Right. The 1918 virus was pretty mild, quite mild, in the first wave and then turned very lethal. But there is not the slightest sign anywhere that that is going to be the case with COVID-19. There have been some mutations that suggest it’s actually maybe more contagious, but not more virulent, so — thankfully. It’s bad enough as it is.

And as you say, we’re not sure what the long-term implications are, whether there will be complications or some damage to the body that does not recover or takes a very long time to recover from. We just don’t know. It’s too new a virus.

AMY GOODMAN: John Barry, we want to thank you so much for being with us, professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, author of, among many books, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. We’ll link to your pieces in The New York Times, the latest, “The Pandemic Could Get Much, Much Worse. We Must Act Now.”

That does it for our show. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Stay safe.

Media Options