Guests

- Bernard Lafayettecivil rights leader, scholar and longtime friend and former roommate of the late Congressmember John Lewis, as well as a professor at Auburn University in Alabama.

We revisit civil rights leader and Congressmember John Lewis’s early years of activism with Bernard Lafayette, one of Lewis’s closest friends and collaborators. Lafayette participated with Lewis in the first Freedom Rides of 1961 as they attempted to integrate buses and faced brutal beatings by white mobs, and was a fellow leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Lewis “knew how to relate to people who were different from him and who had different orientations, different values, different philosophies, and that’s why he was such a great leader,” Lafayette says. “He found a way to make a way.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González, as we turn to look at civil rights leader John Lewis’s early years of activism and his pivotal role in the Freedom Rides of 1961. John Lewis had been heavily involved with lunch counter sit-ins in Nashville, Tennessee, when at the age of 21 he applied and was chosen to be among the 13 original Freedom Riders who rode buses across the South to challenge segregation laws. In this clip from the PBS documentary Freedom Riders, directed by Stanley Nelson, Congressmember John Lewis reads from his application to participate in the first Freedom Ride.

REP. JOHN LEWIS: I wish to apply for acceptance as a participant in CORE’s Freedom Ride, 1961. I’m a senior at American Baptist Theological Seminary and hope to graduate in June. I know that an education is important, and I hope to get one, but at this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life, that justice and freedom might come to the Deep South.

AMY GOODMAN: John Lewis was on the first Freedom Ride when it departed Washington, D.C., on May 4th, 1961, with seven Black and six white passengers. Lewis was also among the first of the activists to face physical violence, when he and two other Freedom Riders were severely beaten by white supremacists in Rock Hill, South Carolina.

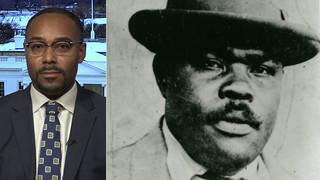

For more on the significance of these rides and John Lewis’s legacy as a young civil rights leader, we go to Tuskegee, Alabama, where we’re joined by his lifelong friend, co-conspirator, former roommate, Bernard Lafayette, a civil rights leader and scholar who participated in the Nashville-New Orleans Freedom Ride in 1961, a leader in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which John Lewis headed.

Bernard Lafayette, now a professor at Auburn University in Alabama, welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us. Bernard Lafayette, we last spoke to you when Freedom Riders, the documentary by Stanley Nelson, came out at the Sundance Film Festival a few years ago. But take us back, how you first met John Lewis, and take us back to the sit-ins and then the Freedom Rides.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE: Thank you very much. And I want to, first of all, say that I really appreciate what you’re doing in terms of documenting history, because our young people can take advantage of understanding the particulars in how things changed, so that they can help to maintain those changes and make even more. So what you are doing is extremely important, and I’m happy to be here to join you.

When I was a student at American Baptist College, John Lewis and I were roommates. And we decided that we were going to participate in the workshops that Jim Lawson was conducting there in Nashville focused on the sit-ins. And it was John who persuaded me to go to the workshops, because I had so many jobs on campus, I did not have time for another workshop. But as John has always been, he’s very persuasive, and he’s persistent. So I went to the workshops just to stop hearing John talk. And lo and behold, I was completely consumed by the information and the strategy and that sort of thing. So, it was John that really recruited me into it.

Now, one thing I want to say is that after the sit-ins in 1960 — and, by the way, we actually desegregated the lunch counters in Nashville in about three months. We were one of the first student groups in our community, in different communities, that did that. One of the things that did that was the fact that we had strategy. We had Diane Nash as our spokesperson, because she had to deal with the media and be able to put it in such a way that it was appealing, because we had to try to win as many people over as possible. To make changes, you cannot do it without winning the sympathy, if not the active support, of the majority. So we got the majority of people in Nashville to really support what we were doing. We had an economic boycott. It was about 90% effective. And that was one of the things that showed us we had support from many different people. So, the many —

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Bernard Lafayette, when you — for the younger people who are watching or listening to this show, could you talk about what exactly were the Freedom Rides? What did you do on a day-to-day basis? And if you could talk about the work that you and John Lewis did to desegregate the Greyhound buses?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE: Yes. Well, after the sit-ins took place and we were able to desegregate the lunch counters, one of the places that we had the, you know, integration was the bus station itself, because we had lunch counters at the bus station, and so therefore we also sat in at those lunch counters. So, the Greyhound bus station was completely desegregated before the Freedom Rides started.

At Christmas of 1960, John Lewis and I decided we were going to take the Greyhound bus, but we were going to sit on the front seat. The Greyhound bus was still segregated, even though the station was integrated, in Nashville. So, I sat behind the driver, and John sat behind the next seat in the front of the bus. Well, we rode all the way from Nashville and got off at Troy, John did, and I continued. And we desegregated that bus.

So, when the Freedom Rides were announced by CORE, Congress of Racial Equality, there was no question that we were going to go on the Freedom Rides. And so happened that John was 21 in February of that year, of 1960, and I was not going to be 21 until July. So, we applied. John Lewis got accepted, but I didn’t get accepted because I needed parental permission, and my parents wouldn’t give permission. My father would say, “I’m not going to sign your death warrant.” So, there was already — before the Freedom Rides started, there was some question about whether or not we would survive.

Well, John went on the original ride, and, as mentioned, he was beaten up there in the first leg, in the first part of the Freedom Rides. But we decided we were going to continue. And the reason why the Freedom Rides continued is because John Lewis came back to Nashville and said, “Let’s go.” So we got permission to take over the Freedom Rides, so I didn’t need parental permission. So, he and I got together, and he took the first group, and I had the backup group, because you have to have a backup group in case if the first group got arrested, the only way you can continue is to have some more people ready to go. And so, we had strategy, and we had experience, and we had leadership ability, and we continued that Freedom Ride from Birmingham on into Montgomery.

In Montgomery, we were met with violence. And this was after we had traveled from Birmingham to Montgomery with armed guards. The federal National Guards and all those people were surrounding us, because they had promised to give protection, the governor. But once we got to the bus station, all of the protection disappeared. And we were on the platform, and Jim Zwerg was beaten up, and John Lewis was clobbered. And I got kicked in the chest and had three broken ribs. So, there was nothing you could do with broken ribs, so I went through the entire Freedom Rides with three broken ribs. I didn’t tell my fellow Freedom Riders, because they might have insisted that I not go. So I just kept quiet. I quietly suffered the entire trip.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you describe what happened, Bernard Lafayette, in Rock Hill, South Carolina? Congressman Clyburn talks now about regretting that he didn’t meet the Freedom Ride bus when it came in, but his wife was pregnant, and she wanted him with her. But the significance and the violence that you were met with? Was John Lewis in Rock Hill?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE: Yes. He was beaten up. And that’s one of the further — first retaliation of the people who were against the Freedom Rides. So, they survived that, and they went on. And the bus got burned in Anniston, Alabama, and the others went into Birmingham. And they were beaten, and that sort of thing, on the buses. So, for the early part of the Freedom Rides, the violence had already manifested itself.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I’m wondering if you could talk also about John Lewis’s leadership role. He became chairman of SNCC and was later succeeded, in 1966, by Stokely Carmichael. And, of course, there was a major shift in SNCC at the time, Carmichael becoming more frustrated and disillusioned with the white liberal establishment of the Democratic Party, after the '64 convention, goes in the direction of Black Power movement and eventually into the Black Panthers. The importance of John Lewis's maintaining his views on nonviolence, and why this was such a core of your activism? How did Lewis deal with the changing debates at that time over nonviolence and Black power?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE: Well, first thing that is important to understand is that it was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It was made up of student leaders from various colleges and universities. And they were pulled together by Ella Baker, who worked for Martin Luther King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And these students were there, in Raleigh, because — at Shaw University, because Ella Baker was a graduate of Shaw University. She was an older woman at this time. But nevertheless, this was a school that was very receptive to this national conference. And we formed that. And Marion Barry, who was one of our students from Nashville, was the first chairman of SNCC. He was a graduate student working on his master’s program, and he showed a good deal of leadership in Nashville, as well. John Lewis showed leadership because he was the president of his class, and then he was the president of the student body, at American Baptist Theological Seminary. So he had that leadership ability all the time. But he didn’t promote himself; others promoted him. It was a student organization. So, John was no longer a student. Neither was, you know, Stokely Carmichael, but Stokely wanted to be the chairman, because he wanted to take the leadership of SNCC. But SNCC was supposed to be for students. And that’s the thing that happened that took it into a different direction, because the students no longer were students in those leadership positions.

So, the whole idea of Black power — now, let me — I don’t know — we don’t have time to do this, but let me give you a hint of what was happening. Stokely and I were cellmates of the Freedom Ride in Jackson, Mississippi, so we stayed up all night arguing with each other about nonviolence. Now, Stokely also felt that Black people should continue to take the leadership of the voter registration movement and that kind of thing. Unfortunately, Blacks who had been subjugated through segregation and oppression for so many years had carved out for — out of themselves and their experience, to be submissive to white folk. OK, I’m breaking it down for you now. OK? When Black students who were part of SNCC went into Mississippi and some places in Alabama and tried to recruit Black people to go down and register, they said, “Get out of here with that mess.” When white students went and told them they were going to come pick them up and they were going to take them to register to vote, they said, “What time should I be ready?”

AMY GOODMAN: Bernard Lafayette, we just have a minute, and I wanted to come back to today. His last public appearance, John Lewis, was at Black Lives Matter Plaza, with the big words “Black Lives Matter” outside the White House, outside Lafayette Park. You were youth leaders then. You were very active in Selma with John Lewis. What message do you, and, do you feel, John Lewis had, especially for young people organizing today?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE: Well, that was one of the genius of John Lewis, is that he knew how to relate to people who were different from him and who had different orientations, different values, different philosophies. And that’s why he was such a great leader, because he didn’t put people down or ignore them or say a lot of negative things about them simply because they didn’t agree with him. He found a way to make a way. And he was always looking at synthesizing our approach rather than dividing.

AMY GOODMAN: Bernard, we are going to have to leave it there. But before we go, I want to wish you a very happy 80th birthday.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Bernard Lafayette, civil rights leader, scholar, longtime friend of the late Congressmember John Lewis, his former roommate. We wish you a very happy birthday.

And that does it for our broadcast. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Stay safe. Save lives. Wear a mask.

Media Options