Guests

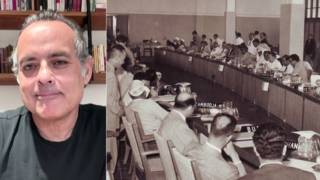

- Keisha Blainassociate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh and president of the African American Intellectual History Society.

Senator Kamala Harris is the first Indian American and first Black woman to be nominated for vice president on a major party ticket, but, as many historians have noted, Harris is not the first Black woman to run for vice president. That distinction belongs to the journalist and political activist Charlotta Bass, who was the editor of The California Eagle for nearly 30 years, one of the country’s oldest Black newspapers, which covered women’s suffrage, police brutality, the Klu Klux Klan, and discriminatory hiring and housing practices. Bass joined the Progressive Party ticket in 1952 on an antiracist platform that called for fair housing and equal access to healthcare. Bass’s exclusion from the public narrative signals a tendency to “sideline Black radical politics,” says author and historian Keisha Blain.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, breaking with convention. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

Tonight, Joe Biden will accept the Democratic Party’s nomination for president, after Kamala Harris became the first Indian American and first Black woman to be nominated for vice president on a major party ticket. In her historic address, Harris paid homage to the women who came before her.

SEN. KAMALA HARRIS: These women inspired us to pick up the torch and fight on — women like Mary Church Terrell, Mary McLeod Bethune, Fannie Lou Hamer and Diane Nash, Constance Baker Motley and the great Shirley Chisholm. We’re not often taught their stories, but, as Americans, we all stand on their shoulders.

AMY GOODMAN: As many historians have noted, Senator Kamala Harris is not the first Black woman to run for vice president. That distinction belongs to the journalist and political activist Charlotta Bass, who was the editor of The California Eagle for nearly 30 years, one of the country’s oldest Black newspapers, which covered women’s suffrage, police brutality, the Klu Klux Klan, and discriminatory hiring and housing practices.

More than a decade before the Voting Rights Act was signed into law, Charlotta Bass joined the Progressive Party ticket in 1952 on an antiracist platform that called for fair housing and equal access to healthcare. Bass ran alongside presidential candidate Vincent Hallinan in a long-shot bid, and they lost to Dwight Eisenhower. But she campaigned with the slogan, “Win or lose, we win by raising the issues.”

For more on Charlotta Bass and the Black women who cleared a path for Harris to be VP pick, as Harris pointed out, we’re joined by Keisha Blain, associate professor of history at University of Pittsburgh and author of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom, also president of the African American Intellectual History Society. Professor Blain joined a panel Wednesday at the DNC on “Progress and the Path Forward” that looked at the unsung heroes of suffrage and Black women’s political power. Her forthcoming book, Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Vision of America.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Professor. It’s great to have you with us. Can you talk about the significance of Kamala Harris being nominated and accepting the nomination for vice president of the Democratic Party, and the people on whose shoulders she stands?

KEISHA BLAIN: Well, first, thank you so much for having me.

I think it’s important to emphasize the fact that Kamala Harris is certainly standing on the shoulders of all the women she mentioned last night, but also standing on the shoulders of Charlotta Bass, as you pointed out. And it’s somewhat unfortunate that she didn’t mention Bass, because, as you pointed out, Bass was in fact the first Black woman to run for vice president. And this took place in 1952 in the state of California on the Progressive Party ticket.

In so many ways, her exclusion last night from Harris’s speech, I think, signals the way we often do sideline Black radical politics, and really, just to echo something that Derecka mentioned earlier, how leftists in the movement tend to be sidelined. And I’m not suggesting that the exclusion of Bass was intentional, but I do think it is unfortunate, and would love to hear more people acknowledging the history and the fundamental work that Bass did long before Kamala Harris.

AMY GOODMAN: Why don’t you tell us that history?

KEISHA BLAIN: Well, one of the things that we know about Charlotta Bass is that she truly engaged in what can best be described as pragmatic activism. And I say that because this is someone who shifted, who moved between organizations. This is someone who was literally — at the same time that she was a leader in the NAACP, she was a leader in the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Anyone who studies history understands just the complexity of being able to function in two organizations that were radically different, even as they were equally committed to Black progress.

And then, on top of that, Bass moved from — supported the Republican Party, then supporting the Democratic Party, and then abandoning both of them when she came to the conclusion that they were simply not doing enough — not doing enough for Black people, not doing enough for women, not doing enough for marginalized groups. And she put up her hands, and she tried a new party, the Progressive Party.

And I think just really thinking about the ways that Charlotta Bass moved in between organizations, shifted parties throughout her lifetime, speaks to her unwavering commitment to advancing Black politics. She never allowed herself to be tied in to one particular group or even one particular perspective. She truly engaged in pragmatic activism, believing that she would do anything, anything possible, to improve the conditions of Black people.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Professor Keisha Blain, could you also explain some of the issues with which she was most preoccupied, from police brutality to media stereotyping of African Americans?

KEISHA BLAIN: Absolutely. She was deeply — excuse me — deeply committed to challenging racism and discrimination and, as you mentioned, even the media. One of the things that she did in 1915, so this is very early in her career in California, was to speak out against the film Birth of a Nation. And she tried to get people — well, certainly she tried to pull the film from being shown publicly. She was not successful in doing that. But what she did do was point out the problems with the film. She was able to rally the community. She openly denounced the film.

And I think her efforts really captured the way that she was concerned with not only, you know, certainly, various aspects of Black politics, but she was concerned with how Black people were being represented on screen. And as a journalist, she understood the power of words, she understood the power of imagery. And I think that’s just one example of how she was truly, I think, a fierce advocate for Black people.

And she was really bold. She confronted the KKK. She addressed police violence and brutality. And her boldness got her in trouble. And it’s not surprising that she was surveilled by the FBI, because she was someone who simply did not sit on the sidelines. She confronted every challenge that she saw, and she tried to come up with solutions to fix the problems.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Professor Blain, why was she branded a communist?

KEISHA BLAIN: Well, she was branded a communist for the same reason that people like W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson and even Marcus Garvey, earlier, had been branded as a problem for the United States. She is someone who certainly embraced leftist politics and ideas, and ultimately she posed a challenge.

The truth of the matter is, she didn’t even need to embrace any kind of radical platform to be branded a communist at the time, because, in the end, to use the term “communist” within that context was simply to try to smear someone, to be able to say, “Listen, this person is not American.” And what we know from history is that the people who were branded communists, whether they embraced communist views or not, were ultimately individuals who stood up, who stood up in the face of injustice, who confronted racism and discrimination. And every time they were vocal, every time they decided they were simply not going to accept Black people being mistreated in this country, all of a sudden they were, quote-unquote, a “communist.”

AMY GOODMAN: In these last few seconds that we have, your next book is on Fannie Lou Hamer. Can you talk about her level of activism, and the struggle you see now in the Democratic Party of the progressives and the establishment, even as history is being made with Kamala Harris being the first woman of color to be nominated as a vice-presidential candidate?

KEISHA BLAIN: Yeah, it was truly wonderful to hear Harris evoke Fannie Lou Hamer. I’ve been deeply invested, certainly, in Hamer’s ideas, and finishing a book on this topic.

And one of the things that I think is important to emphasize is that Hamer ran for office. She ran for office three times. I think that’s important, because we don’t talk about it. Generally, we don’t talk about it. And the reason we don’t talk about it is because she was unsuccessful. But I’m of the mindset that even those stories we have to know. And those stories are powerful, because Fannie Lou Hamer was unsuccessful, Charlotta Bass was unsuccessful, but it doesn’t mean that their stories don’t matter. And it certainly doesn’t mean that we can’t talk about their efforts, because what is key here, it’s not really about winning or losing.

AMY GOODMAN: Three seconds.

KEISHA BLAIN: It’s about how these women ultimately rose to the occasion.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Keisha Blain, we thank you so much for joining us. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Stay safe.

Media Options