Guests

- Greg Mitchelljournalist and author who has written widely about the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings.

On the 75th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, when the United States became the only country ever to use nuclear weapons in warfare, we look at how the U.S. government sought to manipulate the narrative about what it had done — especially by controlling how it was portrayed by Hollywood. Journalist Greg Mitchell’s new book, “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood — and America — Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” documents how the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki triggered a race between Hollywood movie studios to tell a sanitized version of the story in a major motion picture. “There’s all sorts of evidence that has emerged that the use of the bomb was not necessary, it could have been delayed or not used at all,” says Mitchell. “But what was important was to set this narrative of justification, and it was set right at the beginning by Truman and his allies, with a very willing media.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. This is The Quarantine Report.

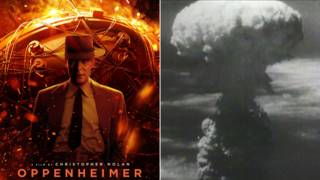

Today marks the 75th anniversary of the U.S. dropping the bomb, the atomic bomb, on Hiroshima, 75 years ago today, ushering in the Atomic Age, August 6, 1945. This is J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist credited with coordinating the creation of the atomic bomb, head of the Manhattan Project, describing his feelings as the first nuclear explosion in history lit up the Trinity blast site in New Mexico, the test site, on July 16th, 1945.

J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER: We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed. A few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

AMY GOODMAN: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” That’s the scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer quoting the Bhagavad Gita.

Well, we turn now to look at how the U.S. government controlled the narrative about the race to build and use the first atomic bomb, especially by controlling how that story was portrayed in the media. This is the focus of a new book called The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood — and America — Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The Beginning or the End is also the name of a 1947 movie by MGM.

We’ll learn more about that and so much more with journalist Greg Mitchell, who’s written extensively on Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings, also the author of Atomic Cover-up and Hiroshima in America, with Robert J. Lifton, and former editor of Nuclear Times magazine.

It’s great to have you with us, Greg. Terrible anniversary, the 75th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb, ushering in the Nuclear Age. Greg, before we talk about the film, The Beginning or the End, that started to recreate a narrative about what happened, for people who are not familiar with what happened then, the significance of J. Robert Oppenheimer, President Truman’s decision to drop the bomb? Tell us why the bomb was dropped, and the criticism at that time through to today, that was not so much heard at the time.

GREG MITCHELL: Yes. Thank you. Happy to be here.

Well, you know, the stated reason for dropping the bomb, which has become what I call the official narrative, really, to this day, as we’ve seen again with the media coverage of the past month, was that it was the only thing that could end the war, it saved a million American lives, the Japanese would not have surrendered, we would have had a costly invasion of Japan, and we really needed to drop the bomb, it was the only thing that worked. This came out in Truman’s initial statement, where he called Hiroshima a military base. So, from the beginning, it was important to communicate to the American people that this was a decent and necessary act.

And, of course, evidence has emerged over the decades which shows that there were alternatives. For example, Truman had just gotten Russia to declare war on Japan, to promise to declare war on around August 9th. And there are many people who believe that Japan — including Truman — believed that Japan would have surrendered quickly after the Russian declaration of war. And so, there’s all sorts of evidence that has emerged that the use of the bomb was not necessary, could have been delayed or not used at all.

But what was important was to set this narrative of justification. And it was set right at the beginning, and by Truman and his allies, and with a very willing media, and then, following that, suppression of evidence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, confiscation of film footage, photographs, censorship office in Tokyo.

My book picks up carrying the story to Hollywood. And I think it tells the whole story of this period and what happened in this crucial turning point, oddly, through this rather entertaining story about this movie, because the way that Truman and the military intervened to make — to adjust the movie and totally get revisions in the script to reflect this official narrative, rather than raise questions about the bomb. And then, ultimately, when the movie came out, it was nothing more than propaganda. And so, really, the story of this movie, and as I tell in the book, it really reflects so much about this turning point in America, where we are set on this path to endorsing the use of the bomb, by most in the media and by many among the public, right to this day.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg, a very quick thing, before we talk about the film, that other film you talk about. The U.S. government secretly filmed the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not just from the sky, but the devastation on the ground, brought that film back to the scientists at Los Alamos, who did the Manhattan Project, made the bombs. And the reports are that these scientists threw up. They were vomiting as they saw this film, horrified, not understanding this would ever be used on Japan. Can you talk about everyone from Albert Einstein to J. Robert Oppenheimer, and how they ultimately felt? That film would be then highly classified for decades —

GREG MITCHELL: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — obviously not incriminating, not sharing nuclear secrets, but because of its huge effect.

GREG MITCHELL: Yeah. Well, in fact, as the book shows, the MGM movie, The Beginning or the End, was actually inspired by one of these scientists. And there were so many of the atomic scientists who were appalled by what had happened with the use of the bomb and the dangers for the future. And so, one of these scientists from Los — excuse me, from Oak Ridge contacted his former chemistry student, the actress Donna Reed, oddly, and Donna Reed set in motion MGM making this movie. But it was —

AMY GOODMAN: This is Donna Reed, the famous actress.

GREG MITCHELL: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Her science teacher?

GREG MITCHELL: Her high school chemistry teacher ended up in the Manhattan Project. He wrote her a letter two months after the bombing, saying that she must get Hollywood to make a big-budget movie that would warn the world about the dangers of remaining on this nuclear path. And, of course, as you mentioned, Albert Einstein was very much allied with that, was probably the leading spokesman for that.

And, you know, Donna Reed set in motion where MGM did start — did launch this movie. At Paramount, they launched a competing movie, with Ayn Rand, of all people, as the screenwriter. So, the book talks a good deal about that. Ayn Rand’s script was ultimately too wacky even for Hollywood, and so Paramount then threw in with MGM on their movie, on their terrible movie.

But in any case, the scientists did — a large number of them did very much turn against the bomb. And partly for their troubles, they were — the leading scientists were surveilled and followed, and their phones tapped, by the FBI.

You mentioned the confiscation of this footage. Just very, very briefly, both the Japanese — a lead Japanese newsreel team and then a U.S. military team filmed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the weeks and months after the bombing. The U.S. footage was all color footage. It was probably all — whenever you see any color footage from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it comes from this U.S. military team. And I told this story first in Atomic Cover-up, a book I wrote a few years ago, and now I’ve just directed a film, also called Atomic Cover-up, that explores how both the Japanese footage and the American footage was suppressed for decades, because it just — it showed too much of the human effects of the bombing.

But that’s kind of a related story to my current book, because Hollywood essentially did the same thing. It was different, but it was taking a movie script, completely revising it, changes ordered by even the White House. A costly scene had to be reshot on orders from Truman and the White House, that would explain his decision to use the bomb more favorably, you might say, which MGM did. So, I mean, it’s quite incredible, just that one example, among many, of a sitting president ordering a movie studio to reshoot the key scene in a movie to reflect more favorably on him and what he did.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Greg Mitchell, I want to turn to the present day and where the U.S. now stands on the use of nuclear weapons, not just 75 years ago. But today you write that 75 years after the first use of nuclear weapons, it’s still supported by a majority of Americans. You cite a recent survey conducted by YouGov and The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists that found that more than a third would support a nuclear strike on North Korea, if North Korea tested a long-range missile capable of reaching the U.S., even if that meant the death of a million civilians.

GREG MITCHELL: Yeah. I mean, what’s really driven my work for almost four decades now is, you know, people say, “Why does Hiroshima matter today?” or, you know, “You can’t change history, even if you could.” But the simple fact is that America continues to have what’s called a first-use policy. It means any president is enabled to order a preemptive nuclear strike — in other words, in response to a conventional war or, as you just mentioned, a threat, a perceived threat, from a rival or an enemy. I think most people still think America would only launch in retaliation, but that’s not true. We’ve had a first-use policy or first-strike policy. And there have been efforts to change it. It’s not happened. So we still have a first-use president.

Now we have a president in the White House who, you know, many people are very fearful of what he might do in a crisis, or in response to a tweet even. He’s not exactly the “stable genius” that he claims to be. And so, we have this policy still in effect.

And that’s why I keep coming back to Hiroshima every year and in books and articles, is because the media, particularly, continues to endorse the use back then. Certainly, no president has really come out against it. Top officials continue to endorse it. And the fact that we’re making — you know, on the one hand, we’ll say, “We must never use nuclear weapons again. They’re too terrible,” and so forth. But the two times we already used them, you know, was “necessary.” And so it’s this endorsement of the use of the bomb then. I think we could all rather easily see if we launched another nuclear attack, the same defenses would come out. We have this in our background. We have this in our history. The world largely condemns it, but it is in our history. And it has been judged —

AMY GOODMAN: And at that time, Greg Mitchell, the number of people who died, believed to be over 200,000, the two atomic bombs that were dropped?

GREG MITCHELL: Yes, 200,000 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I’m going to leave it there, on this 75th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options