Topics

Guests

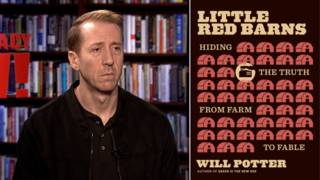

- Rokhaya DialloFrench journalist, writer and filmmaker, as well as a contributing writer for The Washington Post and a researcher-in-residence at Georgetown University.

On the same day France celebrated the induction of American-born singer and civil rights activist Josephine Baker into the Panthéon, far-right xenophobic writer and pundit Éric Zemmour announced he will run for president of France in the upcoming April 2022 election. Many have pointed out the contradiction in these opposing events, even in President Emmanuel Macron’s speech that painted Baker as a model of colorblind unity, when in reality she was outspoken about racial justice. “Celebrating Josephine Baker, who was an immigrant, … while making things difficult for immigrants of today to access to France is a contradiction,” says French journalist Rokhaya Diallo. “France attempts to use the fact that it has been very welcoming to African Americans throughout the 20th century to picture itself as an open and welcoming country.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: “J’ai deux amours” — “I Have Two Loves” — by Josephine Baker. The song was played at the Panthéon in Paris during her induction ceremony Tuesday. This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. French President Emmanuel Macron has inducted the American-born pioneering performer and civil rights icon Josephine Baker into the Panthéon, considered France’s highest tribute. She is the first Black woman, first American, to receive the honor.

Josephine Baker was born in St. Louis in 1906. As an 11-year-old, she witnessed racial violence firsthand when white mobs attacked East St. Louis, Illinois, killing as many as 150 Black residents. At the age of 19, she moved to France to escape racism at home. Soon she became a superstar on stage and screen. In 1951, she returned to the U.S. on tour, refused to play for segregated audiences, was later banned from reentering the United States for a decade after being accused of having ties to the Communist Party. In 1963, she flew in from Paris to speak at the March on Washington, the only woman. Josephine Baker died in 1975, but her legacy lives on.

The induction ceremony for Josephine Baker comes at a time when racism is on the rise in France. Earlier this week, the far-right xenophobic writer and pundit Éric Zemmour announced he would run for president in April’s election. He’s been described as, quote, “the most extreme voice of French racism today.” Zemmour had repeatedly attacked Islam, immigrants and the left. He’s been charged numerous times with inciting racial hatred, including after he called unaccompanied child migrants “thieves, killers and rapists.” Some analysts have described him as the French Donald Trump.

We go now to France, where we’re joined by French journalist and filmmaker Rokhaya Diallo. Her latest op-ed for The Washington Post is headlined “Josephine Baker enters the Panthéon. Don’t let it distract from this larger story.”

Thanks so much for joining us, Rokhaya. Why don’t you start off by telling us that larger story? And then go into the significance of Josephine Baker being recognized.

ROKHAYA DIALLO: Yeah. So, thank you so much for inviting me. I’m very happy. To me, it’s very good news to finally have a woman of color in the Panthéon, which is, as you said, like one of the most prestigious places to welcome the most revered French figures. So it’s something that is very meaningful, because as well as being an entertainer, she was also a hero resisting during the Second World War but also took part to the March on Washington. As you said, she was the first — the only woman.

But the thing is that there are two things that left me with mixed feelings. First, the fact that France tends to use the fact that it has been very welcoming to African Americans throughout the 20th century to picture itself as a very open and welcoming country. But the thing that we tend to forget is that while Josephine Baker was celebrated and dancing on Parisian stages, France was a very violent colonial power, so it was also colonizing Africa and Asia and also the Caribbean, and perpetrating very much violence to people who were colonized and also displaying them in what was called at that time the Colonial Exhibitions, which were basically human zoos, where you could see people coming from the colony to be seen by visitors from Paris and from other regions of France.

So, there was a double standard, with African Americans being welcomed because they were American and didn’t have any historical agreement to settle with France, and, at the same time, other people of color, who were actually submitted to the French state.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Rokhaya, if you could elaborate on that a bit? I’d just like to read a short quotation from the acclaimed writer James Baldwin, who was, of course, one of the most prominent African Americans to seek refuge in France. He wrote about precisely this issue. In an interview, he said, in 1983, “In France, I am a Black American, posing no conceivable threat to French identity: In effect, I do not exist in France. I might have a very different tale to tell were I from Senegal — and a very bitter song to sing were I from Algeria.” Rokhaya Diallo, your comments?

ROKHAYA DIALLO: Yes, it’s very interesting, because it’s still the same today. If you are a Black person from the U.S., you’re mostly seen as American. And the identity, the American identity, is very prestigious, and it has nothing to do with the French colonialism, so you don’t really take part to that sense of guilt or to that confrontational relationship that you may have had with France, because your ancestors were not the victims of the French racism. So, you’re seen as someone who doesn’t have to do with the national context. And you even benefit from the fact that you have now today many African Americans who are very famous, so you have that very positive image.

And actually, I feel the same way when I go to the U.S., because I’m French and I’m seen as a French person. So, when people understand that I’m not African American, I’m suddenly seen as someone that is connected to a country that is very prestigious, that has to do with fashion, with the art de vivre, and such and so. And I no longer have to deal with all the racial issues that are really connected to the African American identity.

And James Baldwin is always used in the French public discourse as an example of France not being as racist as the U.S., which is, to me, not true. But that tells a lot about how that myth, that is very vivid also in the U.S. context of the French being open-minded, is still alive, which is not the case, because, you know, I was born and raised in France, but my parents were born in Senegal. And they were born with the Indigenous status, which was a status that was less than the status of citizen. So, when Josephine Baker was celebrated, my own ancestors, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, did not have the same opportunities. So, if she was a Black woman from Africa or from Guadeloupe or from Martinique, she wouldn’t have had the same opportunities. And I think it’s important to say that.

I think we need to celebrate the fact that she’s finally recognized, but that should not erase the fact that, at the same time, France was not open to minorities, and it was very violent, and it really took part to wars to prevent those people from gaining their freedom and from standing for their own humanity.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Rokhaya, explain also — you said that these issues persist today. How does this kind of racism manifest itself broadly within French society, but also specifically with respect to its immigration policies?

ROKHAYA DIALLO: You just mentioned the fact that Éric Zemmour, the pundit, the former pundit, who is now running for presidency, made his fame on racist statements and also sexist statements. His obsessions are mostly directly toward immigration and Islam. When he said publicly, officially, that he would run for president, he was invited to a TV show, and he said that it doesn’t make any difference between Islam and Islamism, so extremism, and he said that, according to him, Muslims from France should just — how do you say that in English? — they should not be Muslim anymore. They should drop their religion, actually. So, that means that, you know, you can say that publicly and run for presidency and having many people decided to vote for you. So, to me, it’s — and at the same time, his stance is very aggressive toward immigration.

And there is also — in the government of Emmanuel Macron, there is, I can say, a very open anti-immigrant discourse. They voted a law against immigration three years ago, which was one of the worst laws since the Second World War. So, you know, celebrating Josephine Baker, who was an immigrant, who decided to leave her country because she wanted to live a better life elsewhere, while making things difficult for immigrants of today to access to France is a contradiction to me, because, you know, maybe today Emmanuel Macron is preventing the future Josephine Bakers from coming to France, because the barriers to come here are higher and higher.

So, there is a kind of ambivalence, because while celebrating Josephine Baker, who was a celebrity during the last century, today racism is still alive. It’s still expressing itself against immigrants but also against all people of color. For example, in police brutality, we have statistics that say that if you are seen as a Black man or an Arab man, you are 20 times more likely to be checked randomly in the streets by the police than if you belong to any other category. So that means that you have that experience of a person of color in France facing systemic racism, facing institutional racism, and at the same time, a president that celebrates a woman of color who stood against racism, but she stood against racism in the U.S. She never actually said anything against colonization or against racism in France, because the life that she had in France made her be grateful. And I understand why she was grateful, but it’s very convenient to celebrate someone that has nothing to say against France.

AMY GOODMAN: Rokhaya Diallo, in talking about Éric Zemmour and what kind of threat he represents, can you talk about the role of the media? I mean, hasn’t he been tried and convicted for hate speech several times? And what does that mean?

ROKHAYA DIALLO: It’s funny that you ask the question, because the first time he was convicted for hate speech, it was because of a debate we had. You know, he was facing me.

So, to me, Éric Zemmour has been created by the media. He’s been, like — his first book — not his first book, but the first book that made him mainstream was a very violent book against women, against feminism, against the fact that women are gaining more and more space, more and more rights. And then he became a pundit on the public television. It was not even a private television. And he stayed. And even after being convicted, he remained public. He remained on the public television and then on other private media.

So, to me, there is much complicity from the media, because they knew who he was. They were more interested by the buzz, by the noise around his statements, than by the fact of being fair and not perpetrating, not echoing hate speeches. So, actually, to me, there is much complicity to all the people that gave him a mic, who amplified his voice, because they gave him the platform to make him able running for presidency and just polluting the atmosphere with, like, hate speech, with racist statements, with sexist statements, and harassing basically people of color by constantly having aggressive words against them.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Rokhaya, could you explain what you think his actual prospects are as a presidential candidate? And just to give, very quickly, some of the statements that you say have been amplified, he’s approved of people comparing Islam with Nazism, said that parents should only give their children traditional French names, advanced the Great Replacement theory, and said that political power should be with men and not women, whose role it is to have and raise children.

ROKHAYA DIALLO: Yes, he said that, actually, women are unable to be geniuses and to be politicians, because, to him, they don’t have, like, that ability. And he said that without consequence. Also, just lately, he was facing a woman, a Muslim woman with a hijab, with a headscarf, in the street, and he asked her to remove her headscarf in order to be truly French.

And I remember he told me during the same debate that my first name, Rokhaya, wasn’t truly French and that my parents should have named me differently to make me Frencher. And, you know, that was so offensive. That was so aggressive. And I don’t understand why people didn’t challenge him more directly. And now he’s just — you know, he’s just saying —

AMY GOODMAN: We have 10 seconds.

ROKHAYA DIALLO: He’s just saying whatever he wants, without facing real criticize and deep criticize. And I think that we have — that will be difficult, because he’s more provocative than Marine Le Pen, who is the head of the current far right, the National Rally.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you so much, Rokhaya, for joining us, Rokhaya Diallo, French journalist, writer and filmmaker. contributing writer for The Washington Post. We’ll link to her piece, “Josephine Baker enters the Panthéon. Don’t let it distract from this larger story.” I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Stay safe.

Media Options