Topics

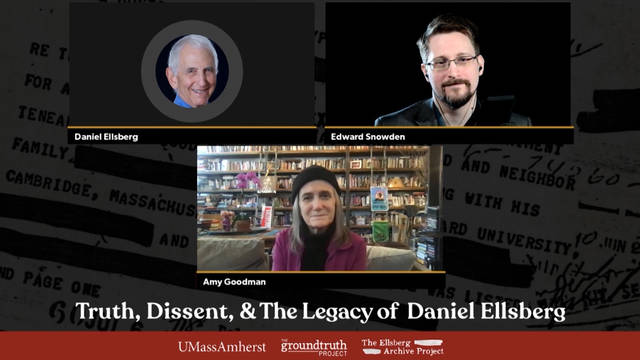

Daniel Ellsberg and Edward Snowden, two of the nation’s most famous whistleblowers, spoke on May Day at a panel moderated by Amy Goodman. The event was part of “Truth, Dissent, & the Legacy of Daniel Ellsberg,” a multi-day conference at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst which is the home of the Ellsberg Archive Project.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Hi. I’m Amy Goodman, host of Democracy Now!, a daily, grassroots, global, unembedded, independent, international, investigative news hour broadcasting on 1,500 public radio and television stations in the United States and around the world. Our theme is going to where the silence is. And that’s exactly what our two guests have done, have committed their life to. I want to welcome you all to this conference, “Truth, Dissent, & the Legacy of Daniel Ellsberg,” on the 50th anniversary of the release of the Pentagon Papers. Yes, Daniel Ellsberg and Edward Snowden have committed their lives to challenging the silence, when they felt for the public to know key information would save lives and change the world. And that’s exactly what they did.

We’re going to start today by talking with both of them about the personal decisions they made to upend their lives and then change the course of history. What would make this 29-year-old intelligence analyst and NSA subcontractor Ed Snowden decide that his idyllic life in Hawaii, he would challenge, he would change, he would leave, to make a difference in the world? And a generation before that, Dan Ellsberg, who was working for the RAND Corporation, had worked for the Pentagon, worked under Secretary of Defense McNamara, worked under Lyndon Johnson, before that had fought in Vietnam, decide that he would risk his freedom, as Ed would do a generation later, to reveal to the world the history of the U.S. involvement with the Pentagon Papers? This is what we’re going to spend the next hour and a half doing, is looking at these decisions.

We’re going to begin with Ed Snowden. Ed was 29 years old, living in Hawaii, when he shared a trove of secret documents revealing that the government was pursuing the means to collect every single phone call, every text message and email in an unprecedented system of global surveillance. After sharing the documents with reporters — he went to Hong Kong to do this — he had to get political asylum. Where would he do this? Attempting to go to Latin America, in the end, it was the U.S. government that determined where he ended up, because they pulled his passport as he flew in transit through the Moscow airport in Russia. And that’s where he lives today.

I want to bring Ed Snowden onto the screen and also Dan Ellsberg. Dan will be joining us by audio instead of by video right now, because he’s suffering a bout of Bell’s palsy. It’s not permanent. It’ll end in a few months, I guarantee him. And it’s not at all painful. But it’ll make it easier for him to just join us by audio. And I welcome you both to this remarkable session, that is really not exactly the culmination, because there will be one after us, but of sessions over the last two days dealing with Dan’s legacy and what he has done in becoming a whistleblower.

So, Ed, it’s once again an honor to be with you. Both of you are Right Livelihood laureates, and I had a chance to speak with you a few years ago from a stage. A thousand people were in the audience. And about that are actually joining us right now in this live stream, to talk with you about that day, back, well, not quite a decade ago, when you left Hawaii. But talk about the lead-up, what you found, and what you chose to do. And by the way, first of all, congratulations on the birth of your first child.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Thank you so much. It’s — you know, I thought blowing the whistle was going to change my life. I didn’t know fatherhood would be much, much harder. But it’s tremendously rewarding. So, really, thank you for your wishes.

When we go back to that idea, what brings somebody to blow the whistle, for myself, at least, it was fundamentally [inaudible]. It was not something [inaudible] —

AMY GOODMAN: Ed, I’m going to interrupt for one second and ask the organizers to turn off Dan’s microphone. That will be helpful. It’ll be clearer to hear Ed. Go ahead, Ed.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Yeah, backstage, give me solo that mic.

Yeah, so, we have — you go into the intelligence community in the United States for a particular reason. And I think that’s because you believe you can do something good for the world. You believe that these intelligence services do good work and can have a positive impact on the world. And by itself, holding this ideal creates a self-selecting sort of cohort, because there’s a lot of people who would never go to work for the CIA or the FBI or the NSA, because they see their work and impact in the world as fundamentally corrosive, fundamentally corrosive. As a young man, you know, I signed up for the Iraq War, when everybody else was protesting it. Why? Because I believed what the government was saying. I believed that it was a just cause, that we were going to free the oppressed from a dictator, you know, that we were going to be welcomed as liberators, and all of these things that we heard on TV. I was not very politically sophisticated. And it takes time for some people who go in. They, you know, raise their hand in dark rooms and swear oaths to these organizations to basically instrumentalize yourself to this greater cause.

I think whistleblowing, in my case, and that path, is recognizing that there is a contradiction between the purpose that the public believes this institution exists to achieve, to serve — and this is to create a freer, more fair society — and what it actually does in secret. Now, this could be a corporation, right? This could be a bank. This could be Facebook. Or it could be the CIA, the NSA, the highest orders of government, the Department of Defense. And that’s really what, for me, brought me down this path, was, year after year, recognizing more and more contradictions, that I had every incentive to ignore. But eventually I could no longer ignore them. And then I started to look deeper. And when you start to pursue that investigative path, to go “What is really happening?” — because, remember, in at least the intelligence community, when you’re talking about classified documents, top-secret documents, they are walled off by this principle of “need to know.” You’re not supposed to know how it all works. You’re only supposed to look at the operations of the government through this little soda straw of your office, of your unit, of your group, directorate, whatever.

Well, eventually, I landed in the Office of Information Sharing, which meant I had to see what everything — what all was going on, so I could decide who themselves needed to know this. And that gave me the ability to look farther and see more, until I saw the big picture. And then I realized, fundamentally, everything that I had been trying to do, everything that the public believed about, you know, what the National Security Agency was doing, was, in fact, creating insecurity. We were violating the rights of every man, woman and child, not only in the United States, but around the world.

And then this raises the question: What do you do about it? And, you know, that’s a long story. We can get there, for my own personal path. But I think one of the most encouraging parts of my journey, as I was getting closer and closer to deciding that, you know, I had a personal responsibility to do something because no one else would — you know, I was always waiting for someone else to go through it; I was talking to my colleagues, I was talking to my supervisors, I was talking to bosses and chiefs in units, and everybody was like, you know, “Don’t do anything. Don’t rock the boat. You know what happens to people who do this. This is above your pay grade” — is I watched a documentary called The Most Dangerous Man in America, which was about what I refer to now as the father of American whistleblowing, one Daniel Ellsberg. And he gave me a model to emulate. And then I read more about whistleblowing. I read more about whistleblowers, in the cases that had come before me — I studied the cases of Thomas Drake, I studied the cases of Chelsea Manning — and recognizing that there was a civil tradition in this country, people who had done things. They had stood up at great personal risk to tell the public an essential truth that was being intentionally denied to them for political purpose. Eventually, you believe that this is what looks more right than going back into the office and perpetuating a system of injustice quietly, day after day.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, talk about what you did in Hawaii, why you ended up in Hong Kong, and how the press was so seminal, a free press, to your release of this information.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Sure. So, when we talk about it, mechanically, I discovered that the government of the United States, in conspiracy with partner governments around the world, most prominently the Five Eyes — these are the Anglophone countries of the world, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada — they had used the advance of technology to change the way surveillance was performed in the wake of 9/11. It used to be that intelligence agencies performed largely what we think of as targeted surveillance. This is where they’ve got somebody in mind who they think is a criminal, they think is a spy, they think is a terrorist, or they think is just someone of intelligence value, right? They’re a parliamentarian in a foreign country. They’re the general of the third Chinese rocket division or something like that. And so they tap their phone, they place a bug, they listen to this person, or they’re spying on satellite communications. But these satellite communications are from point to point between military satellites. So these are fundamentally military communications. They’re not primarily civilian communications. And so, there’s not the same level of civilian sort of impact, as if, for example, you spied on the entire internet and everyone that was communicating through it. This is what I had discovered.

In fact, the government had began monitoring the phone networks en masse in the United States in the wake of 9/11, because they had secretly interpreted the law, that — a law, a provision of the PATRIOT Act, Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act, which allowed them to request any records that were relevant to a counterterrorism investigation. And at the time, this law was protested, under the grounds that this provision might be stretched so far as to let the FBI go to the library and get your reading list. And we saw this as a profound violation of intellectual privacy. How quaint that seems today. Well, in fact, the government secretly took that sort of phrase of law to mean, well, if they’re relevant to a counterterrorism investigation, we can get them; phone records are relevant to a counterterrorism investigation, but we don’t know who all the terrorists are, therefore all phone records are relevant to a counterterrorism investigation. And so they went to the secret, rubber-stamp Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, or the FISA court, and they got them, on a rolling basis, to continuously approve general warrants that said, you know, every 30 days, the largest telecommunications providers in the United States would hand over daily to the National Security Agency the calling records of everybody in the United States and everybody whose calls transited their network, which is basically everybody. In a similar theme, they were performing similar forms of mass surveillance against the internet, which was not known. It was not well understood. And this was actually aided and furthered by the largest internet companies, by Apple, by Google, by Facebook, by Yahoo, and so on and so forth. Today, it’s joined by, you know, groups like Amazon.

And so, the question becomes: What do you do about this? There is this idea that there is a proper whistleblowing sort of channel inside the government, where you can go to, you know, the inspector general, or you can go to the Office of General Counsel in the NSA, and you can tell these guys, you know, “What you’re doing is breaking the law. Unfortunately, like, we need to do something to reform these programs. This goes too far. It’s not correct. There’s some kind of corrupt behavior here.” And they’ll look into it, and you’ll be protected. And if that doesn’t work, you could go to Congress, and then you’ll be protected, and everything will be sunshine and roses, and the problem will be fixed. But what happens when the activity that is unconstitutional, the activity that is criminal, is actually happening with the awareness of the most senior members of Congress — not Congress as a whole body; it’s actually kept secret from the majority of them — but the Gang of Eight — right? — the leaders of both parties, in both houses of Congress, the leaders of the intelligence committees in both houses of Congress, and then, in a willful conspiracy with the executive, they shelter these programs from the oversight of the courts, which cuts out the judicial branch of government?

You know, this is not theory; this is actually what happened. The very kind of mass surveillance that I was so alarmed by was known to the public in a theoretical sense. The ACLU — or, sorry, Amnesty International, famously, had tried to sue the government, and the ACLU represented them, in a case called Amnesty v. Clapper, about mass surveillance. And it got all the way to the level of the Supreme Court in, I believe, January, February, March of 2013. And the Supreme Court said, you know, these things seem like they could have constitutional implications. But if you can’t prove, as Amnesty International, if you can’t prove, as the ACLU, that the government is actually doing this — and you can’t, because the programs are all classified, the government doesn’t avow them, they will not confirm or deny that they exist — you do not have standing to force the courts to hear this case, and therefore the courts can’t enter into the controversy, and therefore the courts can’t decide if what the executive and the legislature are doing is compliant with the Constitution or the law at all.

So, what had happened is the executive branch of government had found a way to hack the Constitution. They had a sort of end run around the protections that we had. And now you, the guy sitting at the desk that knows this is happening, you have a big decision to make: Do you go through the process? Will you be protected? Will you be able to reform this? Will the, you know, president of the United States go, “Oh, you caught me. You know, that was a mistake. I’m going to change that now. Good job”? Or are they going to silence you? Are they going to fire you? Are they going to charge you — as they have in the case of every prominent whistleblower since Daniel Ellsberg.

And I just want to underline the fact that that is not speculation. It’s fact, because we have seen, in the case of Thomas Drake, who’s an NSA executive director who was trying to expose the same kind of programs a decade prior to me, how the government responded when someone came through those proper channels and asked, “What are you guys going to do about it?” And it looked something like this.

VITO POTENZA: If he came to me, someone who was not read into the program, and told me that we were running amok, essentially, and violating the Constitution, there’s no doubt in my mind, I would have told him, you know, “Go talk to your management. Don’t bother me with this.” I mean, you know, you did the — the minute he said, if he did say, “You’re using this to violate the Constitution,” I mean, I probably would have stopped the conversation at that point, quite frankly. So, I mean, if that’s what he said he said, then anything after that probably wasn’t worth listening to anyway.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: And this was consistent with my experience. You know, anything after you start that conversation about “Can we do this?” you know, that’s not the kind of thing that the government wants to hear. And this brings me to the end of your question, which is how. You know, what do you do from there?

And my decision, which was very much founded on the thinking of my predecessors, like Daniel Ellsberg, was whistleblowing is democracy’s safeguard of last resort. When the traditional processes fail, when the executive fails, when the judiciary fails, when the legislature fails, the public is what remains. How do we reach the public in a large, you know, organized society, like we have? Well, we have the press. And we have a press, fortunately, that is allowed to contest the government’s monopoly on control of information. This is what we like to think of as a free press. We can’t say they’re always the best press in the world. But, you know, sometimes we get lucky. And I think when you believe in journalists and when you believe in journalism, it can show you its best.

And so, what I did was I gathered evidence of the wrongdoing and criminal activity that I believed. I provided this as an archive in secret to three different journalists: Laura Poitras, Glenn Greenwald and Barton Gellman. And the idea was to allow them to act as a system of checks and balances against each other and use their different styles of reportage to try to get to the fundamental truth, without me deciding that I was going to be the president of secrets and go out there and publish everything — not to say that that was wrong, but simply to establish if this model could work, and that journalists, acting in competition with each other, could serve the public interest. And basically, then I had to leave the United States to meet with these journalists, because if we were all in the same place at the same time, you know, the government could kick in the door, slap handcuffs, and that would be the end of the story. And these documents were extraordinarily complex. And then, what happened to me after that, I didn’t really have a plan for, which was how everything sort of went so wrong after that, because I was just trying to think, “How do we get the public to know?” And it was amazing to me that it worked at all.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you decide to go to Hong Kong?

EDWARD SNOWDEN: It was — you know, now when you look at Hong Kong, it’s a very different place than it was back in the world of 2013. But it was a question of: How do you get to a place that has basically unfiltered internet, where the U.S. cannot act freely, which is a major media hub? Well, if you try to put that on sort of a matrix, there aren’t a lot of places that meet the center of that Venn diagram. Hong Kong really was one. The ancillary benefit of it was that mainland China is not especially free, or was not especially free at the time, to act openly and freely because of political tensions with Hong Kong’s then-democratic politics. And I, having worked in my last position at the NSA to counter China’s hackers — right? I tracked them using the tools of mass surveillance, and this is how I knew mass surveillance wasn’t theory, because I had actually used it directly myself. I was fairly confident that I understood their capabilities well enough that I could protect myself and the journalists from any kind of local surveillance against them for the period of reportage. And so, that’s what we did.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you share this information. At the time there, it was Laura Poitras, Glenn Greenwald, Ewan McCaskill. And you then had to go underground pretty quickly. Talk about that period. In fact, wasn’t it — you were 29 years old when you did this. It was right around your birthday that the U.S. government brought charges of espionage against you. And you had to figure out how to escape the U.S. making some kind of agreement with Hong Kong to turn you over.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Yeah. So, the government was trying to get the Hong Kong government to extradite me. And I didn’t have any direct contact with them. But, you know, you could read about this in the newspaper. And, you know, officials were on TV making comments about it every day. It was very clear that the Hong Kong government just didn’t want anything to do with this, right? They wanted the hot potato to go somewhere else. Initially, I had thought, you know, “Why don’t I just fight this in the courts, in extradition?” You know, I had an attorney, that the journalists were kind enough to sort of get me in touch with, Robert Tibbo, which was an extraordinary stroke of luck. But he told me, you know, “You’re going to be in jail for the next 10 years, if you fight this, even if you win, because of the way the process is going to work and everything like that. So, if it’s important for you to continue speaking out, you know, you need to start looking to someplace like Iceland or someplace like Ecuador.” And I had to basically find some kind of exit. Well, at the time —

AMY GOODMAN: Julian Assange had been given political asylum [inaudible]

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Precisely. I was going to say, at the time, Ecuador was known to have a quite friendly policy toward whistleblowers, because they had famously granted asylum to Julian Assange. And so that seemed like the best bet. So there was a question of: How do you create, basically, an air bridge from Hong Kong all the way to Latin America without landing in a country that has U.S. extradition? Well, you can’t go from Hong Kong to Ecuador without crossing the flight space, the airspace of the U.S. So you’ve got to go the long way around. And that means, at the time, my ticketed route was, I think, Hong Kong to Moscow, Moscow to Cuba, Cuba to Venezuela, Venezuela to Ecuador.

And what happened was, as soon as I left Hong Kong, then-Secretary of State John Kerry went out on TV. And we still don’t know the basis behind this. You know, I’m sure there will be more memoirs written eventually. Whether the government panicked or whether they realized this was kind of like the gift of an evergreen political attack that they could use to delegitimize me, but they canceled my passport, which meant when I landed in Russia, I could no longer travel onwards. And then I was locked in the airport for 30 days, and sort of the rest is history.

AMY GOODMAN: And that’s where you are today.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: And that’s where I remain today. I still don’t have a passport.

AMY GOODMAN: And what do you face in the United States? Talk about the charges that were brought against you. And again, this was under the Obama administration.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Right. So, under the Obama administration, again, just days after the news broke, the government was reeling from the scandal that they had violated the Constitution and the law on a really staggering scale. And so they sort of trotted out the non-denial denials, where they said, “Nobody’s listening to your phone calls,” which was not a charge that anyone had made. It was the fact they were collecting who you had called, when you had called them, the calling records, your entire social graph of everyone that you cared about and communicated with and when this happened.

And so, they wanted to — and this is also interesting as sort of media study — whenever the government is caught by a scandal, they want to stop talking about the documented harms of their policies and their mistakes, and instead talk about the theoretical risks of journalism in a free society, which is that, “Oh, they could publish too much,” “Oh, they could put people at risk,” “Oh, you know, this person did it because they were, you know, a spy, or they’re after fame, or they were disgruntled, or anything.” They want to start talking about the whistleblower, they want to start talking about the source, and stop talking about their own behavior. And so, this is what they do, primarily, by immediately throwing just all kinds of charges at someone, even if they know so little about what’s actually happened. Of course, just days after, they had no idea. To this day, they still don’t know what documents were provided to journalists. And at the time, you know, they had only the faintest idea because of what they saw on the news.

They charged me under the Espionage Act. And they charged me with theft of government property, which is kind of interesting, because I didn’t steal anything. If anything, it would be like some kind of copyright infringement. I didn’t take any physical documents. I didn’t take any, you know, work computers or anything like that. But what is interesting is that these were almost precisely the same charges that every whistleblower faced. In fact, Daniel Ellsberg was charged with theft of government property. Daniel Ellsberg was charged under the Espionage Act. Daniel Ellsberg was also charged with conspiracy. And I had not yet been charged with conspiracy. Now, well, maybe it’ll come one day. They haven’t done it yet. But I think they’re more careful about the conspiracy charge in relation to journalists today than they were back then. However, at the same time, they had become far more liberal in their application of the Espionage Act, including now against journalists, sort of these publishers and journalists, than they were in the day of Daniel Ellsberg.

AMY GOODMAN: You have said — in fact, you told me, when I spoke to you from Sweden, and at the time, they had hoped maybe you could fly to Sweden, but no country would allow you into — you know, through their borders. You had said, “If I came back to the U.S., I would likely die in prison for telling the truth.”

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Yeah, I mean, I think that’s still accurate. When we look at the war on whistleblowers, that was really amplified by Obama, he charged more sort of sources of journalism under the Espionage Act than all other presidents combined. And under Donald Trump, he had certainly tried to break that record. I don’t believe he was successful. Somebody will have to fact-check me on the numbers there. But now what we have is a bipartisan trend of really trying to quash one of the most important forms of journalism in the United States, really in the world, by going after the sources of it. And to me, that’s a chilling trend.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, you’ve repeatedly invoked Dan Ellsberg and his example, “the most dangerous man in America,” Henry Kissinger called him. And he is joining us, as well, from this home in California. In fact, that’s who this whole conference is dedicated to, on this 50th anniversary of the release of the Pentagon Papers. And Dan, first of all, Happy Birthday on a landmark birthday, your 90th.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: My birthday was April 7th. Yes, that was — thank you. You’re welcome.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, if you could share your story? And then we’ll talk about, you know, the whistleblowers, like Ed, who are facing such serious charges and sentences. But if you can talk about what inspired you so many decades ago, back in 1970 and ’71, to take the information that you had, that very few people had in this country, that history of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, xerox thousands of pages, with your children — and you can talk about this — and get them to newspapers, like The New York Times, The Washington Post and others. Talk about what you were doing and when you decided that you were willing to spend the rest of your life in prison to reveal what you had learned.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Well, some of my secret information, or unusual information, from the point of view of the public, was really shared by very large numbers of people. For example, 3 million people went to Vietnam. And I think virtually all of them realized that the government was lying when they were telling the public that we were making progress or that what we were doing had light at the end of the tunnel, was likely to lead to some sort of success. Now, they disagreed in their minds as to what might make a change, but they were all quite aware that what we were doing was not leading in any way to success and was killing a lot of people on both sides to no effect on either side. And that alone is a basis for realizing that you don’t have a just war to continue, which has to have some reasonable basis for success, no matter how it started and on which side. And that was shared by very many people.

I furthermore knew, unlike most of the people in Vietnam, because I had been a high civil service official, GS-18, in 1964, '65, and knew that the president had very consciously lied at every step of the way for a year as to what he was doing, what he expected, what the prospects were, what the costs were, what the reasons were — in every respect, that we had been lied into war. That didn't make it in itself meaning that it was a wrongful war to begin, but it did mean that there had been no constitutional aspect to it, that Congress had been lied to, that Article One, Section 8, that gives the power of war and peace to Congress, had been flouted, as it had been really ever since Truman in Korea and in nearly every war since then, and very much still, but, nevertheless, to the effect of getting us into war, a presidential war, without congressional involvement. So I knew that in the back of my mind.

I also had seen enough of the arguments in favor and against escalation in ’64, ’65, to be convinced that increasing the bombing was not a solution to the war, putting more troops — and by ’68, we had 500,000 troops in Vietnam. I also knew that the chief of staff of the Army had talked about a million troops — I should say, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Wheeler, had talked about a million troops as early as 1965, and that 500,000 were just [inaudible] on that.

In '68, I had an experience, having been a very loyal, disciplined bureaucratic [inaudible], who was trusted to keep secrets and was known to be able to keep secrets. That's kind of a talent. Not everybody can do it. Some people have a need to tell, sort of, and I didn’t. And it made me self-available then for high clearances, which I’d had in the Pentagon and earlier. And I also — so, I didn’t leak. I thought that leakers were going against the president, going against the president’s policies, going against their promises, certainly. And part of this faithfulness is to your promise not to tell secrets that you’re being trusted with. It’s part of your identity. I’m a trustworthy servant of the president. And that’s who I am. And I’m honored with respect, a very highly respectable, reputable — reputable men, mostly men, nearly entirely in those days, for this. And that’s not a reputation that I can even imagine giving up.

But there was a leak in February of 1968, right after Tet, of the fact that Westmoreland had asked for 206,000 men more, which I knew he had actually done as early as May the year before, but had been refused for the first time. Typically, the president would give Westmoreland a large part of what he asked, but not tell Congress. He would lie to Congress as to what Westmoreland had asked — Westmoreland, who was, pardon me for saying it, a blockhead and not a really good general, but was very reliable, very loyal. And when the president said, say, in May, “I’ve given him all he asked for, which was 40,000,” Westmoreland wouldn’t say to anybody that was a lie, he had asked for 206,000. So, when he renewed that request in February, after Tet, I knew the president was likely to give a large part of that, as he had before, and lie to the Congress, and Westmoreland would go along with it. And we’d move into a war in which not only would we move into North Vietnam, which was part of the plan, but that would bring the Chinese in. And in that respect — again, secret planning — almost everyone agreed that with the Chinese in, we would not again fight Chinese as in Korea without nuclear weapons. The Chinese coming in meant nuclear war. And no one, even people who didn’t really like that idea, did not dare to dispute it in discussions. So, even McNamara and Rusk and others would say, “Yes, yes. When the Chinese come in, we have to use nuclear weapons.” And that was what was in stake.

So, when I saw this leak, I thought for the first time it created quite an uproar in Congress. Eugene McCarthy, other senators made a big fuss about this 206,000, after Tet, which Westmoreland has just described as a great victory, because he killed 50,000 — had killed, actually. For this time, the body count was not overestimated for a change. They really had killed a very large number of North Vietnamese who had come down. And yet you needed 206,000 more? That looked like a contradiction. And I suddenly realized, for the first time, I’ve been going on a wrong principle here, that leaking was necessarily against our interests, against the president’s interests, the wrong thing to do. This was very good. This got a debate for the first time in Congress.

So, I won’t go through the whole story, because I told it in my book Secrets in some detail, but I determined to set out a leak a day of top-secret, very high-level information, which I had access to as a consultant at that time with Clark Clifford. I’m not going through my background that brought me up to that point. But I did have access to it. And I leaked, among other things, Westmoreland’s top-secret report to the president in February — in late January, rather, in which he had a year-end report, in which he said, “We have chased the enemy to the” — this is slight privileged — “chased the enemy to the borders of Vietnam, where we are pursuing him.” We’ve emptied South Vietnam of the Viet Cong, essentially, which was followed, about three days after that report to the president, by the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army occupying every province capital in Vietnam simultaneously, and the embassy in Saigon and most district towns, putting the lie fairly dramatically to this. And as a matter of fact, Westmoreland was fired that day that that came out in The New York Times.

And I was glad of that, not only because of — well, very specifically, because Westmoreland was keeping marines in a besieged condition in Khe Sanh, very like the French besieged in Dien Bien Phu years earlier, in which he was preparing to use nuclear weapons, if necessary, to defend them. And he later, in his memoir, said he thought that would have been a very good idea. He said, “All these liberals and [inaudible] are talking about sending a message to China. Well, it would have been a very good message to send them, right at the borders of North Vietnam or higher, of a nuclear weapon.” That was my obsession, to avert nuclear war. It went back to my own work on nuclear war plans, of which I spoke the other day in this symposium. So, averting nuclear war was my highest priority.

AMY GOODMAN: And let’s be very clear —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: To have Westmoreland fired was very good, from my point of view. Yes?

AMY GOODMAN: Dan, I was just going to say, let’s be clear: This is, again, during a Democratic administration —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: — during the administration of President Johnson.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Yeah. Now, that was my first leaks. That was my — that was my introduction to the idea that leaking might be a patriotic, appropriate thing for a person to do. It’s in the book, got very little notice. And by the way, I won’t dwell on it now, but I’ll give you a secret here about a source, who is no longer with us, all right, or I wouldn’t do it. Only in the last two years, 50 years later or so, I learned that the source of that leak was Leslie Gelb, in charge of the Pentagon Papers. Approximately the last person that I would have guessed would have actually made that, and it was one of the best things he ever did. And it averted, as Nixon — as Johnson, rather, said later, “I would have given Westmoreland what he asked for, and connected with Vietnam, except for those leaks.” And four or five of them were from me. And the first one, though, that set me on that course, was the 206,000 leak by Leslie Gelb. He never did better in his career than that. And he was later a key person in the State Department, the Defense Department and The New York Times later, chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations — couldn’t have said this during his lifetime. Whatever. Would have lost all his associations, practically. He did the right thing. So, I had that in the back of my mind, that that had been effective. By the way, the first thing that General Abrams did when he replaced General Westmoreland, on his first day, was to relieve the marines at Khe Sanh and get them out of there, so that they didn’t need nuclear weapons to defend them. And I felt that had been worthwhile. So, I did assume I would go to prison for that. _The Wall Street Journal said there was a hundred FBI agents looking for the source of those leaks, and I expected to be arrested then. But in terms of avoiding nuclear war imminently, that seemed more than worthwhile.

Well, now, another point came up, actually later that same year, just a few months later. I was introduced — and again, my background, I don’t usually talk about it, hasn’t come up too much. Very important influence on me, probably not, that I know of, on Ed — a difference in our backgrounds here. I met people from the American Friends Action Committee, a Quakers action committee, AQAG, they called them, some of whom had been in a boat. There was a boat called the Phoenix that had gone to interrupt our nuclear testing in the Pacific. And then, later, this same boat was sent to Vietnam with medical supplies for Hanoi and for Saigon, for both sides.

In Saigon, I was there in the embassy and was there the day that members of the secret police pelted these people from their boat with eggs and rocks and whatnot as an embassy operation. They had — they were followers of Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi, Thoreau, Tolstoy, others who were influenced by the idea of direct action, nonviolent direct action, taking responsibility for themselves to oppose wrongdoing, without threatening, without violence.

And at first, to me, the idea of doing something without violence means you’re not doing what you could do. You know, that’s not real power. What I learned when I met these people and studied their work — Barbara Deming, Joan Bondurant, who writes about this, Martin Luther King himself, in Stride Toward Freedom, where says he decided to use the — in the case of Rosa Parks, whom I met later, the Montgomery bus boycott, said the idea of a boycott, at first, worried him, because it was what the White Citizens’ Councils did against any businessman who dealt with Blacks. They would boycott on him and put him out of business. He said, “Well, can we use that same tactic?” And then he said, “It was a matter of withdrawing our support from what we regarded as wrongdoing.”

And by the way, as I say that, something very important occurs to me. Both sides on this issue saw what they were opposing as wrongdoing — namely, the White Citizens’ Councils saw integration as wrongdoing, just as the Confederacy did. And, of course, Rosa Parks and the others thought, “We have a right to ride the buses and not to give up our seats to white men,” as Rosa Parks put it to me.

So, anyway, he decided, to fail to oppose evil is to be complicit with it, and to fail to resist it and to expose it. And you do that by withdrawing your support from it and failing to show deference to it. This is an idea that has some very old roots, but very little demonstration in history, up until Thoreau —

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Let me ask you a question on —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Sure. Sure, Ed.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: — following from that.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Did you ever have an influence like that on your background? Let me ask.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: I mean, for me, as a technologist, the idea that violence was necessary —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Yeah.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: — to effect some kind of change was a little bit foreign to me. Like, I come from a much more sedate world of conflict than Vietnam. Right? Violence, for my generation, was not something that really happened in the United States, unless we screwed up, right? We believed, yeah, or at least were told, that, like, 9/11 was an intelligence failure and all of these things. It was an extraordinary outlier. And really, you know, conflict and war, that’s something you watch on TV. That’s something that happens in some place [inaudible].

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Except for the Civil War and lynching.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Right? You know, when we look at the modern-day, very comfortable, very insulated, sort of American generations, if you join the Army, as I did volunteer to do — I wasn’t afraid of doing violence, as you said. Like, I believed that, you know, sometimes we needed to effect violence in order to secure justice. And I think that’s a natural impulse of young men, who are very much indoctrinated —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Yeah, yeah.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: — by Western culture, for me, and the glamorizing of it in Hollywood and everything. But as a technologist, during a moment in history where technology was reordering the entire world, the idea that, you know, arms would be necessary to expose a wrongdoing, to me, you know, wasn’t directly there. There wasn’t a clear association there.

But what I wanted to ask you is — you know, you say this thing about to do nothing about evil is basically to be party to evil. Now, the politics of, you know, the 1970s is very different from the politics of today. But I have to ask, as something that would be connected to like a national security issue — we’re talking about classification. My experience is, the policies of the security state — right? — the policies of the American government’s domination over certain domains, domestically or abroad, is very enthusiastically supported by members of both parties, at least privately. You know, publicly, they might say the right platitudes, but when it comes to votes, when it comes to motions, when it comes to perpetuating the system, they’re all on board for that. And I wonder — when you came forward, you said you had this plan. You know, there would be story a day for every so often. You had this sort of media strategy in mind. And did you see a difference in the rhetoric amongst people who were responding to, for example, the Pentagon Papers, before your identity was known, and then after your identity was known? And today, this — that’s sort of the first question. The second question is, today, it’s very difficult, I think, for both government and media to differentiate a whistleblower’s political purpose — for example, in your example, an objection to the war — from a partisan objective, where they think, “Oh, they’re doing this for or against this president.” Did you see any of the similar dynamics? And just how did you deal with that? And how did you see that breakdown in the structures of official power in response?

DANIEL ELLSBERG: All right, I’m saying things here that I, in 50 years, have really spent very little time talking about publicly, very important to me privately. And I’ll tell you why. First, reading Martin Luther King and Gandhi and Thoreau had a very big influence on me. But I felt that to talk about Gandhi — by the way, the movie Gandhi is very good — I just saw it again recently — with Ben Kingsley. At one point, there’s the line in it: “Do you want revenge, or do you want change?” A good line. But Martin Sheen is in the movie. I thought to talk about Gandhi is to sound like a cultist or very exotic, Hare Krishna, various things. It’s far removed from American philosophy. And King not, but then people haven’t dwelt on what I learned from King on this so much. So, I thought it’ll sound too special; I won’t talk in those terms.

I am talking now, now because I think this. People think of power as almost inevitably associated with violence, which is also associated, of course, with self-risk and self-sacrifice. So, if you’re not using violence, you’re not risking yourself, and you’re not really pushing in the way that you can. Gandhi’s point, of course, is violence begets violence, which is certainly true, and that it doesn’t get you where you want to do. And, Ed, I’ll tell you, my experience, not only from before, but from the last 50 years, has not disillusioned me on this point. If you go back 50 years, you’re talking about people who romanticized the violence of Third World revolutionaries very much — Castro, Mao, others, and all over the world. And really, in retrospect, that doesn’t look as good as people thought it would then.

And on the other hand, the idea of — the first basic idea of nonviolent action is the strike. And that’s, of course, what Gandhi did do, to a great amount, with a strike. I’ll jump up for one thing right away, for example. I think that in the year 2000, with the Supreme Court intervening in that election the way it did, against a large popular vote in favor of Gore, it was appropriate for a general strike. And that just wasn’t talked about as it should have been.

But on the other hand, the most significant antiwar action, I talk — the best significant leak, I would say, in the war was not the Pentagon Papers, but the 206,000 leak, which prevented our going into Vietnam. I think that Gelb’s leak was far more effective than the immediate effects of the Paragon Papers. I think the biggest effect of the antiwar movement was in the fall of 1969, in what they chose to call a moratorium, which was a weekday stoppage of events in order to have speeches against the war, withdrawal from work and from school, and if you couldn’t withdraw, you wore a black armband to school. In fact, Vice President Agnew’s daughter wore a black armband and was confined to her house for the next two months. And one of the better buttons of the war was “Free Kim Agnew.”

But the fact is, 2 million people on a weekday — not a bright, sunny Saturday, football weekend Saturday, but a weekday — took off from work and school and marched in what they did not know at that time was the Nixon — I’m talking now October 15th, 1969 — Nixon had made threats of nuclear weapons, which were not bluffs, not serious, that he was going to enact on November 3rd, when another strike — and by the way, they called it moratorium because they decided that general strike, which is what it was, was too provocative, too leftist, too inflammatory. So they called it a moratorium, not business as usual.

That kept Nixon from using nuclear weapons and escalating in '69. It was the most effective — I was telling Greta Thunberg, Amy, you know, our hero — I think I speak for both of us; she's my hero, for sure — and I was mentioning to her that with her strikes that she was leading, which were weekday strikes, during Friday, you know, schoolchildren against climate — I told her the history of the moratorium and said, “Think about what they planned to do,” which was one day the first month, two days the second month, three days the third month — in other words, not just one day each time, but an escalating kind of thing, which she hasn’t yet done with the pandemic. But I’m going to go back to her with this notion.

So, anyway, the idea of a strike is the basic notion — and it was very — it was the most effective action. The Pentagon Papers themselves had, as I look back on it — I didn’t expect much because they ended in '68. They didn't tell us what Nixon was doing. And my major message was, contrary to what people believed after Nixon’s election in '68, this war is not ending. He is not ending it. It's going to go on, and it’s going to get larger. That was what I had in mind.

But I didn’t have the documents, because the people who did have them — and Nixon knew they had them, and knew they were friends of mine — did not put them out. As one of them, Roger Morris, said when he left over Cambodia, but without documents and without a press conference, he said to me later, “We should have thrown open the safe.” He’s talking about the threats of nuclear weapons I’ve just described, which were prevented, not by him — he was against them — but he had seen the nuclear targets scheduled for the fall of 1969, and which the people in the streets didn’t even know about when they were doing it. They didn’t know they were preventing that. He said, “We should have thrown open the safes and screamed bloody murder, because that’s exactly what it was.”

AMY GOODMAN: Dan, you mentioned the day of the mass moratorium. Today is actually the 50th anniversary of the May 1st, 1971, massive rally in Washington, D.C., and you were part of an affinity group. You led the affinity group with Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky. They chose you as the commander of their affinity group because they said you had been in Vietnam, you were a marine. You knew how —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Oh, no, that’s an exaggeration. They said afterwards they perceived me as taking over that sergeant’s role, let’s say. Mainly, it came to say — I’ll tell you what I think they were referring to. We’re sitting in the middle of 14th Street, and the theory of Rennie Davis, who just recently died, had said, “If they won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.” Unfortunately, that could have been done in 1970. There were 200,000 people, after Kent State killings and after the invasion of Cambodia, 200,000 people, 400 campuses closed down for the year. And that city was filled. Patricia and I were there. There were buses lined up in front of the White House to protect it from the mob, which was all too — which was nonviolent, which is good.

Unfortunately, the Socialist Workers Party, the leftists, had volunteered to be monitors. And their attitude was accepted — they had armbands. And their attitude was, workers don’t like civil disobedience, and they don’t like antiwar activists. True, both true. And they said, “So we’re not going to do any civil disobedience, right? They don’t like that.” Well, so I watched monitors from the Socialist Workers Party, who, by the way, were thoroughly infiltrated. They were the main target of COINTELPRO, along with the Black Panthers. You know, they had been totally — their constitutional rights totally violated. But here they were pulling people off the streets. We’re sitting down in the middle of the street, in '70 now, right after Cambodia, saying, “We're not doing civil disobedience.”

And Dave Dellinger, one of the very best leaders, nonviolent, pacifist, of the antiwar movement, said his greatest regret of his life was that they made him promise that he would not call for civil disobedience when he spoke to the crowd at midday near the White House. And I was there, too. His great regret was that he kept that promise, and he did not call for — he did not say, “OK, let’s get up and shut the town down,” with 200,000 people and Congress, for once, furious at the president because he had humiliated them by not even consulting any of them before he invaded Cambodia. So, for once, their amour-propre, their pride was hurt, and they were ready to move against the war, cut the funds off and so forth. We could have shut the town down that time. In my opinion, that was a very great missed opportunity. And I can talk about specific votes that went on at that time that were missed.

OK, a year later, we’ve got 25,000, not enough, one-tenth of what we had earlier. So, we couldn’t shut the town down, though that was the idea. But we’re sitting there in the front of — well, I’ll tell you one thing. This was going to be my first arrest, open arrest. This is now '71. The vets had been throwing their medals over the fence, a very crucial time in the peace movement, very powerful image and moment, Medals of Honor and other things. And we were there. I expect to be in jail. I had with me a book that was very influential to me — Barbara Deming, D-E-M-I-N-G, Revolution and Equilibrium, a book that kind of converted me on nonviolence, on Gandhi and nonviolence. And I thought, “Well, if they let me have a book in jail” — which they never do, it turns out — “I'll have this with me to read in jail.”

So, when we go out at 4:00 in the morning, go out in — and taxi drivers volunteered to take us off, mostly Black, actually. “What do we pay you?” “Nothing. No problem. We’re on your side.” And so forth. We went out to 14th Street, and there the first person I see is Ben Spock, the baby doctor, and Barbara Deming, whom I recognized. So I got them to sign my book. I had this book signed by my heroes, at this point.

OK, later, Mark, Howard Zinn, Chomsky, Marilyn Young, Fred Branfman, Mitchell Goodman, the husband of Denise Levertov, a couple of others, Mark Ptashne, are sitting in the middle of 14th Street.

And I think what they’re referring to as my non-com leadership here was that as two police came toward us at about 9:00 in the morning, at right angles, one with his helmet down, as I recall — the visor of his helmet up — the other with the helmet down and with a big club and mace. They came at us at right angles. And I thought, “It’s too early. We just got here. Let’s not end this action right now.” So I said, “Let’s go.” That was me. I took that initiative. I said, “Let’s move.” So, we all got up, and we moved away. And one police — this sounds like a movie, like Mack Sennett — actually did shoot the other police in the face with mace. And his helmet was rolling on the ground, and the club fell on the ground. As I say, if you get the picture, they were coming at us, each other. And they were so determined to come down on us at one time that they came down on each other.

And then we went out through the rest of the day and various things. They ended up arresting 13,000 people that afternoon, after the action had basically been broken. And they put them in RFK — ironically, RFK Stadium. And later, much later, because they didn’t have records on any of them, what they had done was they had just cleaned through Georgetown, picking up every young person, many of whom were children of congresspersons, which was to their favor in the end. So they put them all on. They got a little compensated later.

And I went on — the action having been broken, we had lunch with I.F. Stone. And then I went to New York. Noam went to a veteran’s coffee shop somewhere in Texas. Howard got arrested later that afternoon for asking a policeman, “What are you doing?” when he was beating a young person in Georgetown, and they arrested Howard, naturally, put him in the stadium. And I went to hear McGeorge Bundy at the Council on Foreign Relations, who I used to work for in the Pentagon, lie about the war.

He gave a series of lectures, and I thought, “Interesting.” Because I had already given the Pentagon Papers to Sheehan and to the others. And I said, “Mac, you shouldn’t be saying this. The truth about what you’re saying is going to be coming out.” He was saying that Congress hadn’t been lied to and there was no intention to deceive anyone.

So, that was the mood. And it was a time when, a month later, when we were putting out the Pentagon Papers, all the people working with us — Gar Alperovitz, Janaki Tschannerl — had to do to get people to find us places to stay while the FBI was hunting for us, and we were still putting out more editions of the Pentagon Papers. All you had to do to find a place to stay was to ask somebody with long hair — nearly everybody did, men and women had it then, young people — and say, “We’re doing something that may help end the war, small chance, and maybe quite legally dangerous. Are you willing to help?” And everybody said yes, right away.

There was a movement then. And there was a movement of young people who felt that what was happening in the world, and on race, as well — it really started with the civil liberties movement — was wrong, had to change. And they were ready to risk their careers and their lives to try to change it. And we need that right now.

AMY GOODMAN: That moment, when you decided that what you had, that each person had an ability, perhaps, to help end the war, what you had was this study. If you could talk about how you decided, and including your young children — they weren’t even quite teenagers yet — but you felt, to model for them, to make copies of this report and get it out, but not knowing — even at the May protest, you did not know if Neil Sheehan was actually going to publish this.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: No.

AMY GOODMAN: You had been waiting for months to see if it would publish what you had risked everything for. You were underground at the time?

DANIEL ELLSBERG: That’s right, yeah. Well, no, we went underground when the Times was — stopped publishing. And that day, I called Ben Bagdikian, my friend from RAND, who was the editor — an editor at The Washington Post, and arranged to get it to The Washington Post that day. And having shown it to him, given a channel that night, Patricia and I putting it together — it was in bad, garbled condition — we put on the TV as we were about to leave his apartment, and — that is, the room he had taken at the Treadway Motor Inn near Harvard Square — when he left for the airport. I just happened to put it on, because we were never up at 7:00 in the morning to see how The Today Show actually started. And there were two FBI men, rather identifiable, at our house, 10 Hilliard Street, knocking on the door, with a crowd of neighbors and press watching them. My name had been given the night before by Sid Zion, who had a grudge against The New York Times and wanted to give away their source. He didn’t have a lot of trouble finding out who it was. And having given my name, the FBI now had — who had known for a year. That’s another story, but they had known for a year. And I knew they knew that I had copied these papers. They now had no choice but to go after me on this.

And had we not seen that, we would have gone home, been arrested. And only the Times and the Post, to whom we had just given this, would have had the papers. But the Supreme Court — so, this shows contingency in all these things. Had the Supreme Court been placed with only two papers, that they could stop by injunction — and they did enjoin both of them — I think, almost surely, we would have had our first prior restraint. Five-to-four or six-to-three judges would have said, “OK, give the government more time. Let’s study this. A very great emergency involved here,” and so forth. But as it was, giving the papers out one by one, a new newspaper every day, joining a trail of civil disobedience across the country here — the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the L.A. Times, The Detroit News, The Boston Globe, The Christian Science Monitor — as one of the prosecutors said, it was like herding bees. They couldn’t do it. There was no way to stop it. So, when it really got to the Supreme Court, the issue of stopping it was moot. And that made it possible for them to deny the government, since they couldn’t stop it anyway.

Had we not done that, if we hadn’t copied the papers — which Patricia had stirred me into getting more copies, couple months earlier, by saying, “You talked about doing this for a year. Time to get off your ass and do it.” And she helped me cut “top secret” off the pages where it was still on it, all overnight for a week or so, before we saw Neil Sheehan, which gave us a rather frenzied appearance, in Neil’s eyes, when he came. Had we not had those copies, it would have stopped.

And I just say, at every point along the way for a year and a half now — see, it had been — I had copied the papers and given to Fulbright 21 months earlier than this. And a lot had happened during that time. Then, after this, if there had been — if John Dean, who we heard this afternoon, had not taken on the government to defy the president — granted, he was up for — you know, he was up for prosecution. But to take on the president — and, of course, that is something the others didn’t do. But he couldn’t prove what he was saying without documents. If Alex Butterfield, a Republican, who had been in that office every day, had not taken it on himself to tell the truth instead of lying, which was what he was expected to do and the norm for a White House person, and said that there were no tapes — no tapes. But if Elliot Richardson, counted on to be faithful to the president, the president’s man in every job, from one post to another, had not said, “No, I will not fire the special prosecutor,” and resigned, and then Ruckelshaus had not — in his place, had not refused, causing the public to see, “Wait a minute, two officials are refusing here in one night? What’s going on?” no special — no tapes. With all that, the Supreme Court, appointed by Nixon, ruling against him, nothing would have happened. Nixon, despite the Pentagon Papers, and despite the — everything else, and the antiwar movement is old, and everything, and the offensive, would have stayed in office, and the war would have continued.

So, the likelihood was that the war was going to continue. Nixon was going to bring back the bombing. And we were going to have a war in which American bombers killed Vietnamese, indefinitely, in support of ARVN troops, our — the troops we financed and supported and chose and everything else, our collaborative groups, collaborating with foreigners, essentially, like Afghanistan. How long could that have gone on?

EDWARD SNOWDEN: I was going to say —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: How many years? Twenty years. That’s gone on 20 years now.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: That’s exactly [inaudible] —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Is it about that?

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Let me jump in just for a second, because —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Right.

EDWARD SNOWDEN: — what you just said there is, I think, so timeless. And that’s what people miss, the fallibility of the court, the fallibility of the political process. When people in power are engaged in any kind of policy that has some inertia to it, it’s almost impossible to get them to change. And like you said, you were afraid, you know, that the Pentagon Papers didn’t have this much impact. You said you thought, you know, other things had more impact than the Pentagon Papers. But I’d want to sort of contest that from a certain angle, which is, I think these disclosures, particularly mass disclosures, have a lot more impact than is immediately apparent or directly apparent, where you can show this sort of specific causative link to, because I think when you’re talking about, you know, being inside the White House, the action, you know, that there needs to be a collective there. There is a collective now, not just against the war or against surveillance or anything like that, but against the abuse of secrecy. And this is a collective that you started and, I think, is one of most prominent parts of your legacy and the Pentagon Papers.

In a democracy, where we are supposed to have a public that elects government, that in many ways directs government, we can’t have any policies if we can’t agree on what the facts are. And that’s what — you know, in 2013, with mass surveillance, there were people who suspected it. There were court cases going on, court cases that were going on. There were academics who were, you know, theorizing they knew this stuff was possible. But no one could prove it was happening, just as in the War in Vietnam, you said there were leaks. There were people who knew it. It was an open secret. I was a Pulcinella. But the distance between the suspicion of a thing and establishing the fact of the thing —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Well, let me tell you, yeah, I couldn’t — I couldn’t agree more —

EDWARD SNOWDEN: — [inaudible] as a political act.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Well, you yourself exemplify that so strongly. Without the documents on Nixon, which we still don’t have — we do not have the equivalent of the Pentagon Papers on Nixon or any of his successors — Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia. And these are internal controversies, drafts, estimates of various kinds. We don’t have them still. We don’t have that history. Without them, I never convinced anyone of what I was trying to put out, which was that Nixon has a policy of continuing this war. I won’t go into it now. I talked about it yesterday, on what my understanding of that policy was, which involved keeping Thieu into power for eight years, without American troops, by threatening bombing and by doing bombing and all that. I knew that orally from Mort Halperin, from John Vann and others, but I couldn’t prove it, and nobody wanted to believe it. So, in retrospect, in that sense, it was quite a failure. I didn’t expect so much, but I got less than I expected. The votes didn’t count.

Now, in terms of what you say, Ed, there are two aspects where it did affect things more than I realized at the first. I think it contributed to the mood that in this lied, hopeless war — which I saw as an illegitimate war, having read the earliest stuff, so that it was an unjust war from the beginning, not merely a failed war, not merely a costly war, but had been always wrong. It was an imperial war, in support of the French. I didn’t realize then that we were like the French. We were an imperial power. It wasn’t just an aberration. But at that time, I thought, “Well, somehow we’ve gotten ourselves into a colonial war.” But that wasn’t just, from the point of view of America. So, to me, that was murder.

And murder — I think the moral aspect that entered into me, in coming back to your first question, Amy, what changed me — for years, I had opposed this war, like others, from inside, but in ways — and I didn’t put it in these terms — ways that didn’t risk my own career. I didn’t think of it in a careerist point of view, because that just seemed obviously the most influential way of doing anything, obviously, from inside, I had to be, if we were going to accomplish anything, but eventually, from the outside. What turned out was that the other people I was appealing to inside didn’t want to risk their careers at all, no matter how much they were against the war. Not one of them did. The exception would be Mort Halperin, who came and worked in my defense team. And that kept him from being confirmed in either the Carter or the Clinton administration. For having worked for me, he paid that price. But others simply didn’t do that. They were willing, in effect — no matter how wrong they saw.

Now, put yourself in Ed’s position, of knowing, along with other people, that what — in NSA, that people, just maybe not as smart, but very smart people, knowing this is wrong, it’s unconstitutional. And knowing that, by the way, the perspective not in any of us — you, Ed, me, Chelsea Manning — pure pacifists. On the contrary. Or no secrets. On the contrary, each of us with a career of keeping secrets, even Chelsea, in her, you know, young, young fashion, each of us a volunteer. Here’s three people — we weren’t draftees. We volunteered for war. And we believe what we’ve been told, and we were patriotic in that sense, with our different backgrounds.

And yet, for 39 years, 'til Chelsea came out, I had no one else to point to as an example of what I thought people should do. Now, I didn't like to say, “Do what I did.” You know, that doesn’t sound good. It sounds like self-serving, you know, and, whatever, self-promoting. I didn’t know what to say. And then, finally, I figured out a way to say it, and even put it on posters near the State Department: “Don’t do what I do. Don’t wait. If you have information that the country is being lied into a war, or unconstitutional actions” — in Ed’s case — “are taking place, don’t wait ’til the bombs are falling and thousands more have died. Do what I wish I had done in 1964, five years before I did, seven years before I did publish it.”

AMY GOODMAN: You know, we just have —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: And leak just documents, go with documents.

AMY GOODMAN: We just have eight minutes to go. And I wanted to ask Ed, if you can comment on Daniel Hale, Reality Winner, Julian Assange, now still at the maximum-security person at Belmarsh, what they face and what you face, if you could ever see yourself coming back to the United States, getting a presidential pardon for your fealty to the Constitution?

EDWARD SNOWDEN: So, thank you for asking this, as, actually, I was looking for a chance to jump Dan here, because what he said, “Don’t wait until it’s too late. Act now.” And now, finally, after Dan’s had to wait for 40 years, it has begun. We have created a culture of people who, unlike what Dan said was happening in the 1970s, and unlike what I saw, you know, inside the NSA, is so common, which is, even people who have some opposition stay still, and they stay silent. There is a kind of loneliness of conviction, or of opportunity, or of the intersection of opportunity and conviction, where people see that something is wrong, and people realize they have an opportunity to say something about what is wrong. I think Reality Winner and Daniel Hale and Chelsea Manning, Thomas Drake, Terry Albury and others who have come forward in the last decades, they really prove and have, I think, vindicated Daniel Ellsberg’s approach to the wrongdoing that he saw so many decades ago, because the abuse of power is not something that’s going away.

And look, when we talk about the system, when we talk about how the system responds to it, the way Daniel Ellsberg was charged is the way that, you know, Thomas Drake, the way that Chelsea Manning, the way that I, the way that Reality Winner, the way that Daniel Hale were charged. Government is not very creative in their response to being exposed. The response is retaliation. I don’t expect the U.S. government to ever pardon me, because I don’t believe that they have the political courage — not to laud me as whatever, that’s secondary to it, but to admit that they have made a mistake.

Far aside from the question of pardoning me, who does not need it — I am still free, I am still speaking with you tonight — is someone like Reality Winner, who, you know, the president of the United States right now, Joe Biden, is conspicuously silent on. Has she not suffered enough? Has she not served enough of her sentence for something that she did that was clearly and fundamentally driven, I think, from a publicly minded position? She wanted to inform the public about threats to the stability of the electoral system.

Daniel Hale is one of the most consequential whistleblowers. He sacrificed everything — an incredibly courageous person — to tell us that the drone war, that, you know, is so obviously occurring to everyone else, but the government was still officially denying in so many ways, is here, it is happening, and 90% of the casualties in one five-month period were innocents or bystanders or not the target of the drone strike. We could not establish that, we could not prove that, without Daniel Hale’s voice. Where is the president? Where is the clemency? Where’s the commutation? Where is the pardon? Where is the justice system? And why are we seeing these charges?

I should turn this back to Dan and say, in relation to Assange —

AMY GOODMAN: What about Julian Assange, Ed?

EDWARD SNOWDEN: — in prison — right, the Assange thing. Julian Assange is the first publisher to face charges under the Espionage Act, which is a fundamental threat to the First Amendment and every journalist in the United States and around the world, because if the United States Constitution can’t say you can publish the news without facing charges for it, true and established facts that, you know, the government doesn’t even contest, you can’t do it anywhere, because they’ll simply point fingers at the U.S. and go, “Oh, you know, that beacon of freedom, that bastion of liberty that they present themselves as, they still throw people like Julian Assange in prison.”

But one of the things that’s powerful about Assange’s position, I think, which was, you know, for all of his, what people say, radicalism — a lot of people don’t like him on a personal level — he believed in this concept of lights on, rats out, and this idea that one of the things that whistleblowers did, that was not especially well recognized over the decades, was they can pose a cost on conspiracy. And like Dan was talking about, you know, Nixon and all of these guys, their hands can and have been forced by leaks, large and small, at consequential, crucial points of history. And we would not have that without Daniel Ellsberg establishing this model, people emulating it and willing to take risks, extraordinary risks for themselves, with no guarantee of success, just to tell us something that they believe the public needs to know. And for myself, whatever the consequences are, I’m ready to pay them.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think you can ever get a fair trial in the United States?

EDWARD SNOWDEN: Under the current laws and the Espionage Act, let me let Dan answer that one.

DANIEL ELLSBERG: No, no. Ed, Ed, Amy, whatnot, no one can get, no one, under the Espionage Act, without any ability to explain to a jury why they did what they did, what the impact was, what the possible public benefit was. Without amending the Espionage Act or rescinding it, you cannot get a fair trial for a whistleblower in this case. And Ed would be crazy to come back and stand trial. It is false to say that he would be able to explain to a jury or to the public what he had done.

So, if I may just — I know we only have a couple minutes left, right? So, let me just say, first of all, here, here, to every — I agree, of course, in fact, with everything Ed said. To follow up what I said earlier, I’m saying that after 39 years after the Pentagon Papers, I have been able to say, “Do what Chelsea Manning did,” then, three years later, “Do what Ed Snowden did.” So we do have — and you have Reality Winner and, very definitely, Daniel Hale and the others. They are paying, and likely to pay, a very high price. It’s not something you do — it’s not something you should do for your family for minor offenses of various kinds or just for the record or for history or, I would say, for embezzlement or cost overrun or something like that. You do it when lives are at stake, because you have a chance of saving a world’s worth of lives. I think had Ed Snowden or Chelsea Manning been at a high level — and I’m not talking about a cabinet secretary — had they been an assistant, had they been with access to these documents, there would be in 1990, 1991, no Iraq War. We would not have spent 20 years in Afghanistan. These catastrophes can be changed by individuals putting the truth out. You know, when I began to study civil disobedience back in 1968, I was reading about boycotts. I was reading about martyrdom of various kinds. I wasn’t reading about whistleblowing, because there really weren’t any precedents for it. People had done it, but anonymously. You know, it wasn’t without great effect. It just didn’t — it hardly existed. But it is a category now. Individuals can tell the truth. And that can be very, very powerful, with absolutely no guarantee.

And let me now just, with our last minutes even, let me tell a truth that I’ve had here for 50 years. I refer to it — more than 50 years. I refer to it in references to my book, The Doomsday Machine. If we look up any reference to the Quemoy crisis, which is to say the Taiwan Straits crisis of 1958, where we’re again facing a crisis, over the issue of Taiwan. And it was a top-secret study by Mort Halperin, as it happens, but I am now about to say this without any coordination with Halperin, having not told him that I’m going to say this or anything. I copied that study. It was in my top-secret safe in 1969. And I’ve had it ever since. I refer to my classified study in the footnotes to The Doomsday Machine. I didn’t want to quote it in the text, because I didn’t want to involve Bloomsbury in a legal case, my publisher, on this. But I’m saying it right now.

Go to that and read such things as Dulles saying, “Nothing seemed worth a world war,” says Dulles, “until you looked at the effect of not standing up to each challenge as noted.” And the issue there was: Would we, as the Joint Chiefs all recommended, use nuclear weapons to defend Quemoy and and Matsu and Taiwan, and possibly using seven- to 10-kiloton weapons, with the expectation that the Russians, allies of the Soviets — of the Chinese, would respond and would hit Taiwan? They were talking about, in other words, destroying Taiwan to save it, because our entire world position depended on it. That discussion is going on, I have no doubt whatever, in the Pentagon right now. So, the history of that, in ’58, deserves to be read.

Yes, what I just read you, I am totally responsible for putting out. It is top secret. On appeal, they have refused to put that information out, about a third of Halperin’s study. The other two-thirds are available from the RAND Corporation. And if they want to argue that, there is no question that what I have just said subjects me to the same charges as Julian Assange, as the publisher, or to Chelsea Manning, whose material was only secret, not top secret. This is top secret, and putting it out. And if they want to bring that, I would be very happy to discuss that in front of the Supreme Court. And if I lose, which means the First Amendment loses, that this is still secret and cannot be put out, then my old retirement plan of being in prison will be — will come into effect.

I do believe this is the month we have to be addressing the issue in public of whether we should go to nuclear war over Taiwan or Ukraine or Syria. The commander of the Strategic Command, Admiral Charles Richard, said we must be prepared to go to war with Russia and China, and Taiwan is in that context.

AMY GOODMAN: Dan —

DANIEL ELLSBERG: Let me just say, Amy, he may be a very intelligent guy. I know nothing about him, except that he is sounding asinine. That is criminally insane. War with Russia and China, we are talking there, with any armed conflict, at a high risk of escalation to nuclear war. And if it goes to nuclear war, China with its 300 weapons, or Russia with its thousands, 6,000 weapons, we are talking about the near extinction of humanity. No, there should not be the slightest option, threat or thought whatever of armed conflict with Russia and China now or ever again. And we have to find — transcend that system. It will not happen, unless people in the government show the moral courage of Ed Snowden and Chelsea Manning and Reality Winner and [inaudible], and let us know what these inside plans are being. Without that, I think civilization will not survive the era of nuclear weapons.