Topics

Guests

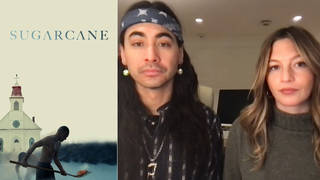

- Cindy BlackstockGitxsan activist for child welfare, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and a professor at McGill University.

The Canadian government is facing pressure to declare a national day of mourning after the bodies of 215 children were found in British Columbia on the grounds of a school for Indigenous children who were forcibly separated from their families by the government. The bodies were discovered at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, which opened in 1890 and closed in the late 1970s. Over the span of a century, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were separated from their families and sent to residential schools to rid them of their Native cultures and languages and integrate them into mainstream Canadian society. “These children are just some of the children who died in the schools,” says Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. “There are many others in unmarked graves across the country.” In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded that residential schools were part of “a conscious policy of cultural genocide” against Canada’s First Nations population.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

The Canadian government is facing pressure to declare a national day of mourning after the bodies of 215 children were found in British Columbia on the grounds of a school where Indigenous children were sent after being forcibly separated from their families by the Canadian government. The bodies were discovered at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, which opened in 1890 and closed in the late 1970s. The Catholic Church ran the school up until 1969.

Over a span of a century, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were sent away from their families as part of an effort by the government and church to rid them of their Native cultures and languages. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded that the residential schools were, quote, “an integral part of a conscious policy of cultural genocide against Canada’s First Nations population.” The commission estimated 4,100 children died while attending residential schools across Canada. The commission’s findings prompted a new search for unmarked graves at residential schools.

This is Chief Rosanne Casimir of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation.

CHIEF ROSANNE CASIMIR: Knowing that, you know, children have went missing, their relations have went missing, and never came home, there was always questions of where. And, you know, there had to be more to the story than they ran away or, you know, what other reason that they may have given. So, I do know that with this here find, you know, it’s about bringing in the advanced technology today to be able to look beneath the surface of the soils and to confirm some of the stories that we were once told.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined now by Cindy Blackstock, Gitxsan activist for child welfare and executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, also a professor at McGill University. She’s joining us from Ottawa.

We thank you so much for joining us, Professor Blackstock. Talk about this horrific finding.

CINDY BLACKSTOCK: You know what? What we know is that First Nations Métis and Inuit children were dying at prolific rates, often related to the federal government’s underfunding of the schools in terms of healthcare and bad health practices, like putting sick kids in with healthy kids, malnourishment, etc., and abuse and neglect. And the federal government knew about this in 1907, had the remedies to address it, and chose not to do it. And this is a history that we see replaying itself throughout the entire history of residential schools. These stories of children dying under these dreadful circumstances were repeated, and Canada continued to do nothing to help them. And so, the important thing to know here is that these children are just some of the children who died in the schools. There are many others in unmarked graves across the country.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Professor Blackstock, could you talk about the role of Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau at this time in terms of these revelations? Isn’t the Canadian government still actively litigating against residential school survivors?

CINDY BLACKSTOCK: Yeah, they are. You know, despite the prime minister accepting all of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action back in 2015, his government is not only litigating against residential school survivors, the survivors from Saint Anne’s residential schools, where there was actually an electric chair — they would literally put children in an electric chair and shock them — and Canada is litigating against the survivors, because it doesn’t want to provide them proper justice and compensation, but it’s also litigating against this generation of First Nations children.

In 2016, we have a legal ruling that found that the government of Canada is racially discriminating against over 165,000 children by providing unequal federal services on reserves. And these are public services that children need. And that inequality was linked to the unnecessary family separations of thousands of children — in fact, in greater numbers than in residential schools — harms to children and, indeed, in some tragic cases, the deaths of children. And yet, Canada — we’ve had to have 19 procedural and noncompliance orders against this government to try and get them to a place to stop the discrimination, and we’re going back to court in two more weeks.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor, I wanted to ask you — specifically, at this place, describe this school, so people have a sense — so often you learn a story, and you learn about the whole world — of what you believe happened to these hundreds of children.

CINDY BLACKSTOCK: Yeah, one of the important things that your listeners may want to know is that our residential school system was actually based off a model in Carlisle Industrial School in Pennsylvania. We sent one of our emissaries — John A. Macdonald, our first prime minister, did — down there, and he modeled our residential schools after that. So, it’s important to know that these stores are probably going to unfold in the United States, as well, with the tragic loss of life of Native Americans.

This particular school is actually right in the middle of a city called Kamloops, which has a population of roughly about 125,000 people. The school sits beside a river. And on one side of the river is a large settlement, and on the other side is the other half of the city. So people would have literally driven past this. And this school was set up in the 1870s and operated until the 1970s. And there are other schools across the country, 130 of them. And some of them were still operating as late as 1996.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And how is it possible —

CINDY BLACKSTOCK: We don’t know why —

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, excuse me. How is it possible for the burial sites to be hidden for so long from public knowledge? And could you talk about the role of the church in this and what you think the church needs to do to atone for these atrocities?

CINDY BLACKSTOCK: Right. So, what we have is really that these deaths would be hidden purposefully by the church and by the government of Canada. We know that when the chief medical health officer of the Indian Department raised the alarm about the unequal healthcare funding in 1907 resulting in the deaths of so many children, that the government of Canada actually cut all of his research funding to document the death rates. And they persecuted him.

So, we have a situation where the children would die sometimes a preventable disease, but in the cases of maltreatment and, indeed, murder, there was a real incentive for those who had done the harm to just bury the kids and not notify anyone. In fact, we have many stories where the other children in the school, if you can imagine, were forced to dig the graves of the children who had died from these various types of maltreatment. So it’s going to be very important to determine the cause of death.

In terms of the churches, the Catholic Church ran this. And we know around the world there has been a lot of scandals about sexual abuse done by priests and other members of the clergy. In this particular case, the Catholic Church was running residential schools all over Canada, including the Kamloops Indian Residential School. And the Catholic Church has really not stepped forward since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. There was a call to action for the pope to apologize, for the church to provide restitution to the victims of its work, and then the third piece is to disclose all the records. It took a lot of the records on residential schools, including who the children were and what happened to them, back to the Vatican, where they were out of reach of residential school survivors who wanted to know the truth and have some source of justice based on those documents. But they’re still in the Vatican, so those need to be returned.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to continue to follow this, Cindy Blackstock, Gitxsan activist for child welfare and executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, also a professor at McGill University.

That does it for our show. Democracy Now! produced with Mike Burke, Deena Guzder, Renée Feltz, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Carla Wills, Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud, Adriano Contreras. Our general manager, Julie Crosby. Special thanks to Becca Staley, Miriam Barnard, Paul Powell, Mike DiFilippo, Miguel Nogueira, Hugh Gran, Denis Moynihan, David Prude and Dennis McCormick.

Tomorrow on Democracy Now!, we will look at the connection of domestic abuse and mass killings. On Thursday, Carol Anderson, The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Media Options