Guests

- Carlos LazoCuban American activist and organizer with Puentes de Amor, or Bridges of Love.

- William LeoGrandeprofessor of government in the School of Public Affairs at American University in Washington, D.C., and a specialist in U.S.-Latin American relations.

After rare anti-government protests in Cuba, Cuban Americans are speaking out to demand the U.S. government end its blockade of the island. But President Joe Biden has responded with new sanctions. We speak with Cuban American Carlos Lazo, who just led a march from Miami to the White House with Puentes de Amor, or Bridges of Love, and says President Biden promised during the 2020 presidential campaign to undo Trump sanctions and return to a more constructive relationship with Cuba. “After seven months, he did nothing,” says Lazo. “We get tired of waiting.” We also speak with Latin American affairs scholar William LeoGrande, professor of government in the School of Public Affairs at American University in Washington, D.C., who says, despite official U.S. rhetoric, almost every president going back to Dwight Eisenhower has found areas of mutual interest with the Cuban government. “There’s a long history of negotiation and cooperation just under the surface of the very real hostility that the United States has had toward Cuba,” says LeoGrande.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show in Cuba, which marked the 68th anniversary of the 1959 Cuban Revolution Monday, after rare anti-government protests broke out on the island earlier this month denouncing the economic crisis during the pandemic and reports of government repression. The shortage of resources comes after a decades-long U.S. embargo and catastrophic U.S. sanctions. Last week, the Biden administration imposed new sanctions on Cuba’s defense minister and Interior Ministry, with President Biden warning, “This is just the beginning.”

This comes as Mexico announced it will send ships with food and medical supplies, including syringes, oxygen tanks and masks, to Cuba. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador addressed the U.S. Monday.

PRESIDENT ANDRÉS MANUEL LÓPEZ OBRADOR: [translated] Rather than blocking, we should all help. It is not conceivable that in these times, they want to punish an independent country with a blockade. I think that President Biden must make a decision about it. It is a respectful call, from no point of view of interference, but we must separate the political from the humanitarian.

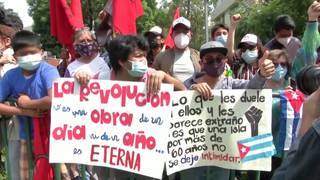

AMY GOODMAN: Meanwhile, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken joined foreign ministers from 20 countries in a statement Monday condemning the arrest of protesters in Cuba. This comes as Cuban Americans and their supporters held dueling protests in Washington, D.C., in recent days. Some called for the U.S. to put more pressure on Cuba’s government, while others condemned the U.S. blockade and support for protesters in Cuba. This is CodePink’s Medea Benjamin.

MEDEA BENJAMIN: Why don’t they come out and say they love the protesters in Colombia or the protesters in Honduras or the protesters in Haiti or the protesters who get their heads chopped off in Saudi Arabia if they protest?

AMY GOODMAN: Medea Benjamin spoke at a protest outside the White House Sunday along with members of the Puentes de Amor, or Bridges of Love project, who marched 1,300 miles from Miami, Florida.

For more, we go to Washington, D.C., to speak with one of the organizers. Carlos Lazo is a Cuban American activist who led the march to D.C., meeting with people along the way. And we’re joined by William LeoGrande, whose latest piece in The Nation, with Peter Kornbluh, is headlined “Now Is the Time for Biden to Restaff the Havana Embassy.” LeoGrande is co-author of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana and a professor of government in the School of Public Affairs at American University.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Carlos Lazo, let’s begin with you. You have just finished this massive march, 1,500 miles, from Miami to Washington, D.C. Why?

CARLOS LAZO: Well, in 2020, President Trump imposed more sanctions to the Cuban people because — during the pandemic. During that time, a year ago, we pedaled 3,000 miles, from Seattle to Washington, D.C., asking President Trump to lift those sanctions at least temporarily, because the pandemic. We arrived to D.C., and President Trump did nothing. On the contrary, he imposed more sanctions. He even prevented the sending remittances through Western Union.

But President Biden, at that time, he was a candidate. He said that he will lift the sanctions on the families, that he will go back to the Obama policies. And we support President Biden during his campaign because we trust his word. And we find that after he got the presidency, he did nothing. After seven months, he did nothing. He just postponed and postponed what he said, that he will relieve the Cuban families.

And we get tired of waiting and waiting. And we decided to march from Miami to Washington, D.C., to call the attention of the American people and to call the attention of everyone about how unhuman and unfair are these sanctions. And we departed from Miami on the 27th of June and arrived here on Sunday, the 25th of July.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Carlos, I wanted to ask you: What was the reaction when you started the march in Miami? Who joined it? And what was the reception you got along the way?

CARLOS LAZO: Well, in Miami, we started the march after a caravan, that Cuban Americans perform there every month, every end of the month. Every Sunday, we have a caravan. And so far, the caravan have 200, 300 people asking for the lifting of the sanctions to the Cuban people, to the Cuban families. Those caravans, unfortunately, have no report in Miami, but they’re happening in the Calle Ocho, 8th Street. They’re happening every, every month.

The reaction of the American people — and we met with people from different backgrounds, from Republicans, Democrats, African Americans, Latinos, Anglos, everyone. And we didn’t find one person who said that it was OK to blockade families. We didn’t find one person that said that it was OK not allowing to send remittances during the pandemic. We didn’t find just one person. We went through Florida. We stopped in different — walking in different cities. We went through Georgia. We talked to different people there, different organizations, Democrats, Republicans, as I said. And nobody — everybody agreed that the embargo should be lifted, and especially during the pandemic, a humanitarian perspective should be applied here.

What was interesting about this trip that we did was that we were trying to educate the people about the blockade, about the embargo and about how this mainly affect Cuban families, and Cuban families in the United States, Cuban families in Cuba. But we find out that there are not just one blockade. Talking to those communities, we get also educated. We went to meet with African American farmers in Georgia, and we learned about the lack of opportunities that they have, the lack of support with loans, the lack of government support. And we find out that there were more than one blockade, not just a blockade to Cuba, but many communities in the United States suffer also from a type of blockade.

And we are joining forces here. We are learning from each other and at the same time doing a common front to fight with all these inequities and injustices. And proof of that is the event that we had in front of the White House, the 25th of July, where Cuban Americans, Americans from all backgrounds, from many different organizations, joined us asking President Biden to honor his word: lift the sanctions to the Cuban people.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’d like to bring in William LeoGrande also. You’re the co-author of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. Could you talk about some of these secret negotiations that have gone on for decades between the United States and Cuba? And also, I wanted to ask you a question, because we’re going to be having — an additional question. Our next segment is going to be dealing with Guantánamo Bay and the Muslim prisoners that are still there. But a lot of Americans are not clear why — what is the legal basis for the United States still to have a base in Cuba, a country that it has had a belligerent relationship now with for so long?

WILLIAM LEOGRANDE: Well, let me start with the negotiations. Every president since Eisenhower has actually held some sort of negotiations with Cuba, the one exception being Donald Trump. But over the years, presidents of the United States — despite the relationship of hostility between the United States and Cuba, presidents of the United States have recognized that there are some issues that are important to the United States, and you can only make progress on them by talking to the Cubans, whether it’s migration or counternarcotics cooperation or getting to peace in southern Africa and in Central America. And over the years, those negotiations have produced a lot of bilateral agreements that served U.S. interests. Just in the last two years of the Obama administration, after he began the process of trying to normalize relations with Cuba, Cuba and the United States signed 22 bilateral agreements on issues of mutual interest. And when Trump closed the door to relations with Cuba, there were 17 different negotiations underway to implement some of those agreements and to try to reach new ones. So there’s a long history of negotiation and cooperation just under the surface of the very real hostility that the United States has had towards Cuba.

Now, with regard to Guantánamo, when the United States intervened in Cuba in 1898, the Spanish-American War, one of the things that we forced Cuba to do in order to become an independent country was to sign something called the Platt Amendment, which gave the United States really what amounts to neocolonial rights in Cuba. And one of those rights was naval bases. Guantánamo was one of those bases. And in 1933, we renegotiated a treaty with Cuba that gave us the right to stay in Guantánamo in perpetuity. Now, as you can imagine, after 1959, Fidel Castro demanded that we get out of Guantánamo, and repudiated, abrogated that treaty, while the United States, of course, refused. And there was really no way that the Cubans could force us out, because, obviously, if the Cuban government were to try to push Guantánamo — or, push the United States out of Guantánamo by force, that would give the United States an excuse to invade Cuba.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it’s just an astounding story that here Biden is criticizing Cuba for human rights abuses, and then the U.S. is showing Cuba what respect for human rights would look like in Cuba, the example being the Guantánamo prison, where 39 men are still being held — well, actually, 37, around that, right now. And we’re going to talk with two lawyers for those men who were just released, held without charge for more than 15 years at Guantánamo. But I want to turn to Republican Senator Ted Cruz, whose father was Cuban American, speaking to Fox Business, welcoming the Biden administration’s pushback on the Cuban government.

SEN. TED CRUZ: I’m glad that the administration is announcing targeted sanctions on the Cuban regime. I think this is the least they could do, and they’re finally moving in the right direction.

AMY GOODMAN: So, there you have president — you have Senator Cruz, rarely, complimenting President Biden. He joins with the hard — with the Cuban American senator also, Menendez, the Democrat from New Jersey, and Senator Rubio of Florida. Who is Biden trying to please, William LeoGrande? And why are you calling for the restaffing of the Havana Embassy? What would that do?

WILLIAM LEOGRANDE: Well, first, I think that the Biden administration is being — or has been, in its Cuba policy, driven by domestic politics. And this, unfortunately, has been a problem for Democrats, really, for almost 30 or 40 years now. Ever since the end of the Cold War, Cuba has not been a very important foreign policy issue for the United States. But because of the power of the conservative Cuban American lobby in South Florida, it has become a very important domestic political issue. As we know, Florida is always close in presidential elections. Most Cuban Americans are concentrated in South Florida, and so they become a really pivotal constituency in elections. The Democrats lost South Florida badly in 2020, and I think that’s thrown the fear of God into the Biden administration. There are already some more conservative Democrats in the House and in the Senate who are urging Biden not to do anything to relax relations with Cuba, despite his campaign promises, for fear of losing even more ground in Florida in the 2022 midterm elections.

AMY GOODMAN: And the issue of restaffing the embassy, why this matters?

WILLIAM LEOGRANDE: Well, it matters enormously. In 2017, Donald Trump reduced the U.S. Embassy staff and the Cuban Embassy staff here in Washington by about two-thirds, leaving really just a skeletal staffing. And one of the things that happened was that the consular section of the U.S. Embassy in Havana was closed to Cubans. And that meant that the United States was essentially violating the 1994 migration agreement that ended the famous rafters migration crisis during the Clinton administration. We had agreed at that time, to end that crisis, to accept a minimum of 20,000 immigrant Cubans every year. And we’ve been doing that ever since 1985. But the Trump administration simply ignored that agreement, closed the consular section, and the number of immigrant visas that we have given to Cubans during the Trump administration fell by 90%.

What that means is that in the midst of this really terrible economic crisis in Cuba, Cubans have no safe and legal way to emigrate to the United States. The Cuban family reunification program, which we use to reunify Cuban and Cuban American families, was suspended by the Trump administration. So, by restaffing the Embassy and reopening the consular section, the Biden administration is taking an important step toward reopening safe and legal ways for Cubans to migrate, so that they don’t have to get on unseaworthy small boats and rickety rafts and risk their lives in the Florida Strait.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I wanted to bring Carlos Lazo back into the conversation. Could you talk a little bit about the practical ways that the sanctions affect daily Cuban life? And especially talk about the importance of remittances, the money that Cubans in the United States send back to their families, because, obviously, throughout Latin America, not just in Cuba, the money, the remittances from Latino migrants in the United States are some of the biggest sources of foreign income to these countries, greater than any U.S. aid to the countries.

CARLOS LAZO: Yes. Well, I want to go back to Professor LeoGrande about the closing of the Embassy. And that’s one of the ways that these sanctions affect the Cubans here and over there. People, in order to get a visa, if they get it, they have to travel to another country. It’s almost impossible to get a visa. And if you do it, you have to spend a lot of amount of money. Also, the reunification program, closed by Trump in 2017, that allowed an expedited way for Cuban Americans and for Cuban families to reunite, this was closed, and this affects Cuban families.

The remittances — in October last year, President Trump prohibited Western Union to send money to Cuba. The source of income of the Cuban families, many people receive income from remittances. And by doing this — and it’s just not to Cuba — to the United States, let me tell you. For a long time, if you lived in another part of the world, you cannot send money to Cuba through Western Union, because United States laws prohibit that. Also they closed the airports in all the provinces, meaning that they prohibit American airlines to fly to other airports other than Havana. This really affect Cuban families in the middle of a pandemic. There is no tourism in Cuba now because the pandemic. And one of the main sources of income for the country is the tourism and also the remittances. If there is no tourism and there is no remittances, they end up empty-handed. They don’t have a way to survive. I have — in my personal case, I have my aunt. She lives in Cuba. For many years, I have supported her. She is an old lady, and I sent every month money to her through Western Union. And right now it is almost impossible to do that, first of all, because there are no flights, because the pandemic and all the restrictions.

And the families are desperate. Desperate. Hunger is happening in Havana, in Cuba right now. And this brings me back to 1960. There was a memo written by a secretary of state, Mallory. And he says, at that time, that the only way to get — to overthrow the Cuban government was by creating hunger and desperation in the Cuban population. And then the Cuban population will rebel against that government. And it seems that this memo is happening today. It seems that the United States is in the — pursuing creating hunger and desperation in the Cuban people to achieve, finally, the overthrowing the Cuban government. The United States —

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And —

CARLOS LAZO: Yeah — the United States claims about the human rights violation in Cuba, but I think that one of the biggest human rights violations on Cuba happens because they blockade over 11 million families in Cuba, 11 million people.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, William LeoGrande, I wanted to ask you about this issue of the blockade. What do you think the recent statements by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, very strong denunciation of the sanctions — and he also said, “Look, the rest of the world has been voting repeatedly to end these sanctions. It’s time through actions, not just words.” What do you think the impact of a figure like AMLO, such a close — a nation so close to the United States and so important to the United States, might do?

WILLIAM LEOGRANDE: Well, you know, Mexico never supported U.S. sanctions against Cuba. Even when every other country in Latin America went along with OAS sanctions back in the 1960s, the Mexicans refused. You know, Mexico is obviously one of the most, if not the most important Latin American country to the United States. One would hope that this appeal by the Mexican president might be heard in the Biden administration.

Particularly I think it’s appropriate because the way that President Obrador framed it was in terms of humanitarian assistance and the humanitarian need in Cuba today. And that need, as Carlos has said, is really extreme. And, you know, historically, the United States, even in the midst of our conflicts with Cuba, has been willing to provide humanitarian assistance to the island in situations of natural disasters — hurricanes, for example. Even George W. Bush, when he was president, offered Cuba humanitarian assistance after a terrible storm.

So, it’s not unprecedented for the Biden administration to take some actions that would relax elements of the embargo, make it easier to ship medical equipment and supplies to Cuba, make it easier to send food to Cuba, make it easier to send remittances, most importantly. Carlos is absolutely right about remittances. They are a critical component of the basic income of more than half of Cuban families. And with remittances largely cut off and with the tourism sector now shut down because of COVID, the Cuban government is essentially broke. They don’t have the foreign exchange earnings to be able to import basic necessities like food and medicine and fuel. So there’s a humanitarian crisis on the island. It’s already increasing pressures for migration. And it would be in the interests not just of the Cuban people, but also in the interests of the United States, for us to do something to relieve that misery.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you both for being with us, William LeoGrande, author of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations Between Washington and Havana. We’ll also link to your piece with Peter Kornbluh in The Nation that you just wrote, “Now Is the Time for Biden to Restaff the Havana Embassy.” And thanks so much to Carlos Lazo. He is a Cuban American activist with Puentes de Amor, or Bridges of Love, just completed this 1,500-mile march from Florida to Washington, D.C.

Next up, as the United States imposes new Cuban sanctions, citing human rights abuses, we’ll look at the U.S. military prison at Guantánamo. Stay with us.

Media Options