Guests

- Jeffery Robinsoncriminal defense attorney, documentary filmmaker and executive director of the Who We Are Project.

- Sarah Kunstlerlawyer, writer and documentary filmmaker.

- Emily Kunstlerdocumentary filmmaker.

As the United States heads into the Martin Luther King Day holiday weekend, attempts by Democrats to pass major new voting rights legislation appear to have stalled. We examine the new award-winning documentary “Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America,” which follows civil rights attorney Jeffery Robinson as he confronts the enduring legacy of anti-Black racism in the United States, weaving together examples from the U.S. Constitution, education system and policing. “The entire purpose of this film is to ask people to take a long hard look at our actual history of white supremacy and anti-Black racism,” says Robinson, the former deputy legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union. “That is something that has been really erased from the common narrative and creation story about America.” We also speak with Emily Kunstler and Sarah Kunstler, the directors of the film.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

As the nation heads into the Martin Luther King Day federal holiday weekend, Democrats have been dealt a major blow in their effort to pass new voting rights legislation. On Thursday, Democratic Senators Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin announced they would not support changing Senate rules to prevent Republicans from using a filibuster to block the legislation. Senate Majority Chuck Schumer had promised a vote on the rule changes by Martin Luther King Day, which is Monday, but that won’t happen. On Thursday night, Schumer adjourned the Senate until next week.

Civil rights groups have been leading the campaign to strengthen voting rights on the federal level as Republicans have passed laws in 19 states over the past year to make voting harder, especially for people of color.

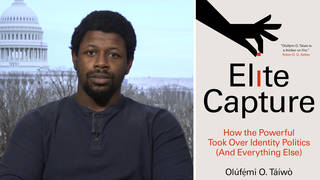

We turn now to look at a stunning new documentary titled Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America. The film centers on a talk given by Jeffery Robinson, the former deputy legal director of the ACLU. This is the film’s trailer.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: If I make the statement to you, “America was founded on white supremacy,” you could say, “Jeff, that’s an extreme statement.” And what I would say to you is, “Don’t believe a word I say about it. All you have to do is go look.”

BRAXTON SPIVEY: Slavery had nothing to do with the war, because they were treated as family.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: I don’t know if he can be reached. But if no one tries, he definitely won’t change.

AL MILLER: Lynchings took place in this very spot. Everybody needs to know what happened, because it’s a part of our history, American history.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: America has demonstrated its greatness time and time again. And America is one of the most racist countries on the face of the Earth. Those two things are not mutually exclusive. Virginia passed a law an enslaved person’s death while resisting a master is not a felony. Would you look at those words, please, and think about the videos you have seen in the past 10 years?

POLICE OFFICER: Shots fired!

JEFFERY ROBINSON: It’s still not a felony.

TAMI SAWYER: We want all Confederate memorabilia removed from our city.

UNIDENTIFIED: We have to save other lives.

CHIEF EGUNWALE AMUSAN: It is too big of a story.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: And this is who we are in America.

AMY GOODMAN: The trailer of the new documentary Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America, featuring attorney Jeffery Robinson. In a moment, he’ll join us, along with the filmmakers. But first, another clip from Who We Are.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: I was 11 years old in 1968. And to my young eyes, we had been on a path toward racial justice that was amazing. There was the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act. We were winning on buses and at lunch counters. We were seemingly, to me, at a tipping point, where we were either going to roll forward with this incredible momentum on racial justice, or we could roll back. And then April 4th happened, and King got shot in the neck. And it felt like the whole thing just rolled back, because then came Richard Nixon and the war on drugs.

We’re 50 years later now. And once again, young activists in America are making Americans take a look in the mirror in terms of our true history of race and racial prejudice. Once again, the young activists are calling us to account. Once again, America is having to look at issues of race dead in the eye. And once again, we are at a tipping point. And the question for all of us in this room is: What are we going to do about it?

AMY GOODMAN: An excerpt from Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America.

We’re joined now by Jeffery Robinson, who wrote the film and is the featured subject in the film. And we’re joined by the film’s directors, Emily and Sarah Kunstler, who have made a number of films together, including a documentary about their father titled William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe.

Jeffery Robinson, I want to begin with you by reading a quote from the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. from 1964. He wrote an article for The Nation as activists were pushing passage of the Civil Rights Act in the Senate after it passed the House. King wrote, quote, “There are men in the Senate who now plan to perpetuate the injustices Bull Connor so ignobly defended. His weapons were the high-pressure hose, the club and the snarling dog; theirs is the filibuster. If America is as revolted by them as it was by Bull Connor, we shall emerge with a victory. It is not too much to ask, 101 years after the Emancipation, that Senators who must meet the challenge of filibuster do so in the spirit of the heroes of Birmingham.”

Dr. King continued, invoking the powerful memory of the four young African American girls killed in the racist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, and two more youth killed in the protests that immediately followed. He wrote, quote, “There could be no more fitting tribute to the children of Birmingham than to have the Senate for the first time in history bury a civil rights filibuster. The dead children cannot be restored, but living children can be given a life. The assassins who still walk the streets will still be unpunished, but at least they will be defeated.”

Those are the words of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King in 1964. He could have given this speech on the floor of the Senate today. Jeffery Robinson, if you could respond to that, and then in the context of the whole subject of your film?

JEFFERY ROBINSON: Well, I think this is one of the very interesting things. What you just read would likely be banned in any number of states that have, quote-unquote, “anti-CRT” laws. And this is the danger of trying to erase the facts of our history. We can’t look back and say, “Wait a minute, we’ve here before. We’ve been at this exact place before.” And if we don’t learn from what happened then, we are doomed to take the wrong path as we go forward.

The entire purpose of this film is to ask people to take a long hard look at our actual history of white supremacy and anti-Black racism. That is something that has been really erased from the common narrative and creation story about America. And this film and the Who We Are Project is intent on getting it back, getting it back for all of us.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s bring Emily and Sarah Kunstler into this conversation, the directors and producers of this remarkable film, Who We Are. Talk about how you got involved. It is premiering this weekend.

SARAH KUNSTLER: Thank you, Amy.

Well, I heard Jeffery speak, and it was at a — Emily hates when I say this. It was at a continuing legal education seminar, which Emily says makes it sound boring. And I expected it to be boring. And I also — the topic was the history of racism in America, and I expected to know it already. That’s the hubris with which I went into hearing Jeffery speak for the first time. And I walked out of that room, and I couldn’t look at anything the same way ever again. I mean, Jeffery’s talk changed my life.

And I’m a filmmaker, and I make films with my sister. And I knew, having left that room, having had that transformative experience, that there was certainly a film there, and really felt an obligation to help Jeffery bring his talk to the widest audience possible. So I called Emily, and I got her on the hook, and I said, you know, “I know what you’re doing for the next five years.” And that’s how the project started.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to another clip of the documentary, Who We Are.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: This is what luck looks like. I have worked as hard as anybody in this theater to get where I am today, and I am proud of that. But I am lucky. I was not the smartest kid in my neighborhood. And that ball that we saw rolling back when King got shot, the only reason I didn’t get crushed by that ball is that I had unicorns for parents, who figured out some way to get their kids into a situation where they had a better chance to succeed. And if that’s what it takes to have a legitimate chance at success, having unicorns for parents or just having dumb luck, is that really a country that you want to live in?

And so, when you hear words, when you hear the concept expressed of white privilege, I am begging you to think about that in different way. White privilege doesn’t mean that you haven’t worked hard. It doesn’t mean that you haven’t overcome obstacles. It means that you walk through the world differently than the Black and Brown people in this country. It does not take away from your hard work or your accomplishments at all. It simply says this playing field is not level.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Jeffery Robinson, the main subject of this film, Who We Are, dealing with racism in America. As you talk about your growing up, Jeffery, if you could elaborate on that? And also, talk about your son and how he inspired you, as well, your son who is also your nephew.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: Well, in 2011, my sister-in-law, who lived in New York, passed away, and she was a single mom raising my nephew along with her mother. And my sister-in-law passed away in April, and my mother-in-law passed away later that year. So Matthew was 13, and he moved from New York to Seattle. And my wife and I didn’t have kids, and all of a sudden we did, and there’s a 13-year-old young Black male in my house.

And I had been a criminal defense lawyer for decades and working on issues of racial justice that entire time. And it got very, very personal. And I was scared, so I started to read. And I don’t really know what I was looking for, but I know what I found. And what I found were all kinds of facts about the history of white supremacy and anti-Black racism, the role that those two things played in the founding of our country and going forward from there. And I was shocked, because I grew up in Memphis, Tennessee. I was born in 1956. I didn’t have to read about the civil rights movement; it’s what I walked into when I left my home. My older brother and I integrated a Catholic school in Memphis in 1963. And despite having one of the best educations in America, I was finding out this material in my fifties.

And after gathering this material over a period of time and being kind of overwhelmed by it, my training as a criminal defense lawyer kicked in. And one of those precepts is, if you have a huge amount of information that’s really confusing, put it into a timeline and see what happens. And when I saw what happened, the reaction that Sarah described upon hearing my talk was the reaction that I was having. And I felt ashamed and ignorant because I didn’t know this. And I didn’t know the context of this information, from all of my training and education. And after I forgave myself, I figured I’d blame my teachers, because I needed somebody to blame. But then I figured, “How can my teachers teach me something that they were never taught?”

And that’s why I started this presentation, and that’s why I formed the Who We Are Project. I believe that America has to have what William Burroughs would call a “naked lunch moment” with our true history. And Burroughs defined a “naked lunch moment” as that moment when everyone has to look at what is really on the end of their fork.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to another clip of Who We Are. This is about the U.S. Constitution, about policing and white supremacy.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: Article IV, Section 2: no freedom for a runaway because slaves have to be returned to owners on demand. And people have said that the folks who wrote our Constitution were brilliant. And I agree with that: They were brilliant. And they were sneaky, too, because they said, “You know, somebody may try and amend the Constitution and get rid of Article I, Section 9.” So, in Article V, they said you can’t amend Article 1, Section 9 until 1808. This is how important the concept of white supremacy was to the people that founded the country. When they were talking about life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, they saw that as being completely consistent with enslaving people.

The law picked a side. If you read the historians, they will tell you that modern-day police departments were originally formed, especially in the South, in slave patrols. I am not saying that modern-day police officers are members of a slave patrol. They are not. There are law enforcement officers all over America who are fighting for racial justice and constitutional and decent policing in our communities. But I will tell you this: People in my community, from my great-great-great-grandfathers on down, have had a reason to fear that badge, because the people wearing it and the weapons and guns that they carried were used to oppress us. So, the next time you’re wondering, “Why is there such animosity in the Black community when it comes to policing? Why is there such concern?” it’s in our DNA.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Jeffery Robinson, the main subject of Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America, that is premiering this weekend in theaters around the country as a New York Times Critic’s Pick. Jeffery, the kind of conversations you have with your nephew right now as you talk about the police?

JEFFERY ROBINSON: The conversations with my nephew were very difficult, because he was 13 years old. He had just lost the two parent figures in his life. He was moving from New York to Seattle, Washington, and living with uncle and auntie, who were now mom and dad. And so, the conversations were very complex.

The conversation about policing was a version of the same conversation that my father had with me. And when my father had that conversation with me, he told me it was the same conversation that his father had with him. And there was a clip in the film where I called my parents unicorns. And, believe me, they were. But they were not unique. There were Black unicorn parents all over America who were making their way through the landmines and the roadblocks to give their kids the opportunity to have a better future than they had.

So, I think the thing that I connected to here is the fact of the importance of our history, because erasing our history means erasing all of those things that literally are some of the root causes of why America looks like it does today.

AMY GOODMAN: Emily Kunstler, you and Sarah, your sister, have long worked on films that deal with racial justice. I was with you on a panel to do with the Central Park Five, a case that your father was deeply involved with. Talk about what Jeffery Robinson’s speech and the kind of — and the way you have framed it, because you’ve done something very unusual. For people listening on the radio, they’ll hear him speaking. For people watching, they’ll see all the images of the times he’s referring to, but then you also include so many clips of the historic moments throughout time that he refers to.

EMILY KUNSTLER: Well, Jeff’s speech, just on its own, his presentation, is totally riveting. And we felt so lucky to be able to work with that as the basis for this film. But we really wanted to bring this to the largest audience possible. And in order to do that, we had to make it into a movie and bring it out of the realm of the PowerPoint presentation.

So, Jeff travels to give his presentation, and we would travel with him wherever he would go. And as he would travel, us and a few producers and a cameraperson, a sound person, all in a 15-passenger van, we’d find stories of people that would bring different aspects of Jeff’s presentation to life, so we could have a real emotional hook through real human experience for our audience. We knew that that would be crucial to make this into a film, that and incorporating Jeff’s story into the film, as well. There are some very personal stories about Jeff’s personal experience and his family’s experience of racism in their lives that we also incorporated.

AMY GOODMAN: What most struck you in those? What were some of those stories?

EMILY KUNSTLER: The trip to Memphis, I think, was a very powerful experience for all of us, getting to go to Jeffery’s home that had been purchased for Jeff’s family by a white family because Jeff’s family was unable to purchase a home, visiting his school and meeting with his best friend and his best friend’s older brother, who was also Jeff’s coach, and learning about something Jeff had never even heard about before, about an experience of racism that he had been shielded from by his coach. Those were experiences where there wasn’t a dry eye in the room. It was very powerful moments for us.

AMY GOODMAN: I was just going to say, Jeff, I mean, that moment where you begin to break down, where you learn about what was really behind a story you lived when you were just playing basketball.

JEFFERY ROBINSON: Yes. And I should say that — and I want to say that when Emily was describing that my parents couldn’t buy the home, it’s not that they couldn’t buy the home, it’s that the sellers wouldn’t sell to them. And that’s why the white family got involved, and the folks sold the home to the white family, thinking that’s who they were selling it to, but with a white family was actually buying it for us.

The incident you’re talking about with my coach, Dick Orians, was an incredibly emotional moment for me, because we had been to — this is probably 1967, so I’m in the fifth or sixth grade, and Dick is 21 years old. And we are in Walls, Mississippi. I am at this grade school that my brother and I integrated, so I’m the only Black kid on our basketball team. And when we show up in Walls, Mississippi, for this tournament, I was told and our team was told the clock was broken and the referees couldn’t get there, so they were canceling the tournament. And so we were turning around to go back to Memphis. And then Dick ran up and said, “Hey, they fixed the clock, and the refs just showed up, so we’re going to play.” And we played.

And there was a point during the game where one of the kids I was playing against called me the N-word. And I came over to the bench during a timeout, and my dad was there, you know, in the little bleachers, and I told him what happened. And he just looked at me and said, “So, do you want to cry, or do you want to play, or do you want to quit?” And I said, “Well, I want to keep playing.” And he told me, “Then forget about it and keep playing.” You know, there are kids that grew up when I did, Black kids all over the South, that had experiences like that. And so I definitely remember that experience, and I thought that was it.

What I came to find out from Dick is that when we walked into the gym, the other coaches came up to him and said, as Dick described it, “We don’t allow Blacks to play in the gym.” I guarantee you they did not use the word “Blacks.” And so, Dick said, “OK.” And he had a decision to make, at 21 years old, in Walls, Mississippi, maybe three years after people had been — the civil rights workers had been disappeared for standing up for racial justice. And this 21-year-old kid figured out, “My team is not playing unless Jeffery plays. I’m not going to go to 11-year-olds and put this on them.” So he came up with this reason that we were leaving, until the pastor in the Mississippi church saw us leaving, figured out what was happening, and Dick and the pastor went into the gym, got the parents together, and I guess they decided to suspend the rule for this one time.

AMY GOODMAN: Jeffery, I want to end the film when you go to Selma, Alabama, where you spoke to former state Senator Hank Sanders to talk about the Edmund Pettus Bridge. In ’65, voting rights activists were brutally attacked crossing the bridge as they attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery on what became known as Bloody Sunday.

SEN. HANK SANDERS: Edmund Pettus was a powerful leader in this area. He was a former U.S. senator. Most importantly, he was the grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.

FAYA ORA ROSE TOURÉ: Highest leader.

SEN. HANK SANDERS: When this bridge was completed, I think in 1940 or so, they wanted a symbol. They wanted to name the bridge after somebody who would send a signal of “stay in your place,” because symbols are more powerful than words. And so, this is a very powerful symbol. Every time someone crosses the Edmund Pettus Bridge, it gets in them. Every time someone sees a photo of it, it gets in them. Every time one sees something on TV, it gets in them. So, that’s why, in the Senate, I got introduced a resolution to change the name from Edmund Pettus Bridge to the Freedom Bridge.

FAYA ORA ROSE TOURÉ: And the state of Alabama last year passed a law that said you cannot change the names of any of these so-called iconic white supremacist symbols.

AMY GOODMAN: That was attorney and civil rights activist Faya Ora Rose Touré and, before her, former Alabama state Senator Hank Sanders, speaking to Jeffery Robinson, who is the subject and writer of this remarkable documentary that’s called Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America. Emily and Sarah Kunstler direct it. We thank you all so much for being with us. That does it for our show. I wish everyone a safe Martin Luther King Day weekend. I’m Amy Goodman. Wear a mask.

Media Options