We speak to award-winning journalist Jonathan Katz about his new book “Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire.” The book follows the life of the Marines officer Smedley Butler and the trail of U.S. imperialism from Cuba and the Philippines to Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and Panama. The book also describes an effort by banking and business leaders to topple Franklin D. Roosevelt’s government in 1934 in order to establish a fascist dictatorship. The plot was exposed by Butler, who famously declared, “War is a racket.” The far-right conspiracy to overthrow liberal democracy has historical parallels to the recent January 6 insurrection, says Katz.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

As the January 6th House committee and federal prosecutors continue investigation into last year’s deadly insurrection at the U.S. Capitol and Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the election, we turn to look at a largely forgotten effort to topple the U.S. government in the past.

It was 1934. Some of the nation’s most powerful bankers and business leaders plotted to overthrow President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in order to block the New Deal and establish a fascist dictatorship. The coup plotters included the head of General Motors, Alfred P. Sloan, as well as J.P. Morgan Jr. and the former president of DuPont, Irénée du Pont. The men asked the celebrated Marine Corps officer Smedley Butler to lead a military coup. But Butler refused and revealed what he knew to members of Congress. This is a clip of General Smedley Butler speaking in 1934.

MAJOR GEN. SMEDLEY BUTLER: I appeared before the congressional committee, the highest representation of the American people, under subpoena to tell what I knew of activities which I believed might lead to an attempt to set up a fascist dictatorship.

The plan, as outlined to me, was to form an organization of veterans to use as a bluff, or as a club at least, to intimidate the government and break down our democratic institutions. The upshot of the whole thing was that I was supposed to lead an organization of 500,000 men which would be able to take over the functions of government.

I talked with an investigator for this committee who came to me with a subpoena on Sunday, November 18. He told me they had unearthed evidence linking my name with several such veteran organizations. As it then seemed to me to be getting serious, I felt it was my duty to tell all I knew of such activities to this committee.

My main interest in all this is to preserve our democratic institutions. I want to retain the right to vote, the right to speak freely and the right to write. If we maintain these basic principles, our democracy is safe. No dictatorship can exist with suffrage, freedom of speech and press.

AMY GOODMAN: At the time, Marine Major General Smedley Butler was one of the most celebrated Marine officers in the country, having played key roles in U.S. invasions and occupations across the globe, including in Cuba, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Mexico and the Philippines. But Smedley Butler later spoke out against U.S. imperialism, famously writing, “War is a racket. It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. … It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives. … It is conducted for the benefit of the very few, at the expense of the very many,” Butler said.

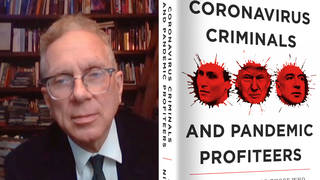

We’re joined now by the award-winning author Jonathan Katz, author of the new book Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire, also the author of The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Jonathan. This is a fascinating book. I mean, for people who don’t know about, for example, this attempted coup of 1934, can you talk more about exactly how it unfolded? The parallels to these days are quite interesting, but let’s start with the original story that took place, what, like 90 years ago.

JONATHAN KATZ: Yeah. So, it actually starts in 1933. A representative of a prominent Wall Street brokerage house named Gerald C. MacGuire starts trying to recruit Smedley Butler to — it actually starts out as like kind of an internal plot to get him to speak against Franklin D. Roosevelt taking the dollar off the gold standard at an American Legion conference in Chicago, but it broadens from there. And by 1934, MacGuire is sending Butler postcards from the French Riviera, where he’s just arrived from fascist Italy, from Berlin, and then he comes to Butler’s hometown of Philadelphia and asks him to lead a column of half a million World War I veterans up Pennsylvania Avenue for the purpose of intimidating Franklin Delano Roosevelt into either resigning outright or handing off all his executive powers to a all-powerful, unelected cabinet secretary who the plotters who were backing MacGuire were going to name.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Jonathan, didn’t Butler also claim, in addition to these corporate leaders, that there were folks like Prescott Bush involved in this, the father of George Herbert Walker Bush and grandfather of George W. Bush?

JONATHAN KATZ: So, there’s actually a kind of a game of broken telephone going on with his name being involved in this. So, Bush was actually — Prescott Bush was actually too much involved with the actual Nazi Party in Germany to be involved with the business plot. Bush was a partner at Brown Brothers Harriman, which is still a major investment bank based in New York, across the street from Zuccotti Park, their headquarters. And Bush was the — Brown Brothers Harriman was the subject of a different investigation by the same congressional committee, because that committee’s ambit was to investigate all forms of sort of fascist influence and all attempts to subvert American democracy. And because Brown Brothers was part of a separate investigation, they end up sort of in the same folder at the National Archives, and then it ends up sort of getting mixed up in a documentary that came out about 10 years ago. So that’s actually a misunderstanding. Butler never brought up Prescott Bush’s name. But it was because Prescott Bush was too involved with the actual Nazis to be involved with something that was so homegrown as the business plot.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And in terms of why they were recruiting Butler, his importance in the early and mid-20th century as a military hero, could you talk about that, as well?

JONATHAN KATZ: Yeah. So, Butler was — you know, he was the Zelig. He was like the Forrest Gump of American imperialism in the early 20th century. He joined the Marines in 1898. He lied about his age. He was 16 years old. And he joined to fight in the Spanish-American War, or the Spanish-Cuban-American War, against Spanish imperialism in Cuba. But from there, he rides a wave of imperial war, and he’s everywhere. He’s in the Philippines. He invades China twice. He helps seize the land for the Panama Canal. He overthrows governments in Nicaragua, in Haiti. He invades the Dominican Republic, etc. He’s also a general during World War I.

And so he had this very, very long and renowned résumé in the Marine Corps — he was twice the recipient of the Medal of Honor — that made him a big star in America. And he was also — he had a reputation as being sort of a Marines general, like he was somebody who had the deep and abiding respect of his enlisted men. And because of that résumé of having overthrown a lot of democracies overseas and also having, you know, the loyalty of so many members of the Marine Corps, that, for the best — the best as we can tell, is why Gerry MacGuire, and probably his boss Grayson Murphy, went to Butler to lead their putsch.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, we want to get into this early history, because it is fascinating. When you, you know, mention the Philippines, when you mention Cuba and Puerto Rico, people are not really aware — most people, I think — of what the U.S. role was. But just on this plot in 1934, what did General Motors and J.P. Morgan have to do with this? What was the Liberty League? And how far did this go?

JONATHAN KATZ: So, the reason why we know about the Liberty League’s involvement is because Gerry MacGuire, who is the representative of this Wall Street firm, tells Butler at this meeting in 1934 that very soon an organization is going to emerge to back the putsch. And he describes them as being sort of the villagers in the opera, that they would sort of be operating behind the scenes. And a couple weeks later, on the front page of The New York Times, this new organization is announced, the Liberty League, and it started by the du Ponts, Alfred P. Sloan, all of the people that you just mentioned, and is also directly connected to MacGuire, the guy who’s recruiting Butler, because his boss, Grayson M.P. Murphy, who is really, I think, the linchpin of this thing, is the treasurer of the Liberty League.

And what the Liberty League was, was it was basically a consortium of extremely wealthy capitalist industrialists who hated Franklin Roosevelt. They also had the involvement of two former Democratic presidential candidates, Al Smith and John W. Davis, who were anti-New Deal Democrats. And basically, you know, their public-facing goal — and they were very open about this — was to dismantle the New Deal, which FDR was trying to use to save Americans, to put millions of Americans back to work and save Americans from the Depression.

What we don’t know is how far the — maybe the more senior members of the Liberty League, like the du Ponts, had gotten in the planning. And the reason why we don’t know is because the congressional committee that Butler testifies in front of, which is headed by John W. McCormack, who goes on to become the longtime speaker of the House, Samuel Dickstein, who was a Democrat of New York, they cut their investigation short. The only people who testify are Butler, a newspaper reporter who Butler has enlisted in sort of an independent investigation, Gerry MacGuire and the lawyer for one of the maybe lower-level industrialists who’s behind this, the heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune. And so, absent that more detailed investigation, we just don’t know the extent to which the du Ponts, for instance, actually were involved in the planning of the business plot. They may have already been fully involved and just stopped planning once Butler blew the whistle, or it’s possible that Murphy hadn’t got them involved yet. We just can’t say.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what was the reaction of the press at the time to the claims of Butler? It might be instructive, given the things that we’re going through today.

JONATHAN KATZ: Yeah. It was ridicule. So, you know, this was big news at the time. The story ran on the front page of The New York Times, but the Times, you know, they kind of divided it in half, and half of the column inches on the front were just sort of these, like, hilarious denials by the accused. Time magazine, which was owned by Henry Luce, the billionaire son — or, millionaire son of missionaries to China, you know, ran sort of a satirical piece mocking Butler. The Times mocked Butler further in an unsigned editorial. It was basically peals of laughter.

And a couple months later, once the committee had issued its final report — again, they didn’t do a full investigation, but they did enough to say that they were able to, in their words, verify all the pertinent statements made by General Butler and that, you know, something was planned and may have been put into action at such a time as the plotters, however many there were, saw fit. That conclusion got far, far less attention. And to a certain extent, it really — it kind of — you know, it severely damaged, I would say, Butler’s reputation among the establishment, among the American elite. And it sort of helped consign the business plot to maybe not the dustbin, but kind of the forgotten marginalia of American history.

AMY GOODMAN: So, this is critical. I mean, you’re talking about them fighting FDR, calling him a socialist, the New Deal, and then jump forward almost a century to today. Talk about the parallels you see with the Capitol insurrection and beyond that.

JONATHAN KATZ: Yeah, the parallels are legion — no pun intended. I mean, so, one clear set of parallels is that Gerald MacGuire, who’s the bond salesman who tries to recruit Butler, one of the places that he went in Europe in 1934 to gain inspiration for this plot — again, it was a totally homegrown thing, but he was looking to fascist movements in Europe for inspiration — was to Paris, where, six weeks before MacGuire arrived in Paris, there was a riot of far-right and fascist groups. They tried to storm the Parliament in Paris to prevent the handover of power to a center-left prime minister. They were animated by a kind of a crazy conspiracy theory, an antisemitic conspiracy theory, that involved somebody who had committed suicide. Sort of, you know, there was a conspiracy that he hadn’t really killed himself. And that group, one of the groups that participated in that riot, called the Croix-de-Feu, or the Fiery Cross, was, in MacGuire’s terms, exactly the sort of organization that he wanted Butler to lead.

You know, you look at that, that is one of the closest historical parallels to what happened on January 6, you know, sort of a motley assortment of groups, some of which hate each other, others were kind of unaligned, but they’re all sort working together in this effort to overthrow a democracy, prevent the transfer of power to a center-left prime minister, who they see as a stalking horse for communism or socialism. And really, I mean, that’s one of the closest historical antecedents. And there are many others, including, I mean, just the fact that it was a fascist coup being plotted in the United States to overthrow American democracy at a time when liberal democracy was seen by a lot of people as being on the way out. And, you know, we see the same things here today.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Jonathan, if you could just briefly, in a few seconds, give us a sense of how Butler changed from being a soldier of imperialism to an anti-imperialist? What caused him to have this transformation?

JONATHAN KATZ: Yeah, I mean, so that was really like the central question that I was trying to answer for myself in writing Gangsters of Capitalism. I would say that there wasn’t one single moment. To a certain extent, Butler is kind of returning to his roots. Among other fascinating things about the guy, he’s a Quaker from Philadelphia’s Main Line. And he gets into his first war at the age of 16, fighting against imperialism and tyranny. And to a certain extent, over the course of his career, he sees that the primary beneficiaries of his and his Marines’ interventions are the banks, are Wall Street, are American politicians. And then he sees the ways in which, you know — excuse me — imperialism abroad gets reimported as authoritarianism and fascism at home. And that’s really why he ends up spending the last 10 years of his life decrying the military-industrial complex, writing War Is a Racket, and trying to — ultimately, trying and, of course, failing to prevent the outbreak of World War II and the United States’ entry into it.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to thank you so much, Jonathan Katz, for joining us, award-winning journalist, author. His latest book, Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire. His writings appear on TheRacket.news.

Media Options