In a major victory for animal rights, a jury in Utah has acquitted two animal rights activists who each faced up to five-and-a-half years of prison time for rescuing two sick piglets from Smithfield’s Circle Four Farms, one of the world’s largest pig farms. During the 2017 rescue operation, activists with the group Direct Action Everywhere found piglets feeding on their own mother’s blood, pregnant pigs held in gestation crates too small for them to turn around in, and sick and feverish piglets left to die of starvation or be trampled. The long-awaited decision sets the stage for a “right to rescue’’ legal precedent, which would allow anyone to rescue dying animals from unsafe conditions. For more, we speak with one of the activists, Wayne Hsiung, who represented himself in trial and says the jury decision is “a resounding victory not just for transparency and accountability in factory farms but for the idea that animals are living beings and not just things to be thrown away in a garbage can.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

In Utah, a jury acquitted two animal rights activists this weekend who faced years in prison for rescuing two sick piglets from Smithfield’s Circle Four Farms in Utah, one of the world’s largest pig farms. It’s a major victory for the animal rights group Direct Action Everywhere, which has been fighting to establish a “right to rescue” animals in distress. During the rescue operation, activists with the group found piglets feeding on their own mother’s blood, pregnant pigs held in gestational crates too small for them to turn around in, and sick and feverish piglets left to die of starvation or be trampled.

This is Wayne Hsiung, Direct Action Everywhere, in a video filmed during a rescue at Smithfield’s Circle Four Farms.

WAYNE HSIUNG: So, we’ve seen piles of dead piglets, piglets who starved to death, who have been crushed to death. And we have a little one here whose face is covered with blood. She’s half the size of the other piglets. She’s going to die unless we get her out. Her mother’s nipples have been cut and are so overused that they’re bleeding. And you can’t even get milk out of them. Her children are literally drinking blood to survive. And this little piglet in the corner here, whose face is covered in blood, and she’s down on the ground, she’s not going to make it. And so we’re going to take her out. We’re going to give her the medical care she deserves, and then we’re going to take her to sanctuary, and hopefully she survives.

AMY GOODMAN: Wayne Hsiung went on to describe what he found outside of a dumpster at the Smithfield pig farm in Utah.

WAYNE HSIUNG: So, we’re outside of a dumpster at Circle Four, and they literally just took a mother pig who is sick and not able to stand any longer, threw her in here headfirst with a pile of probably a hundred dead babies. And when we just got here, we could still hear the blood dripping from her body. And, you know, she probably died from blunt force trauma to the head. She’s covered with all sorts of disgusting feces, blood, rotten corpses. And again, this is what happens at every single pig farm in the world, because they treat these animals as if they’re just things. But they’re not things, they’re living creatures. And they deserve better than this.

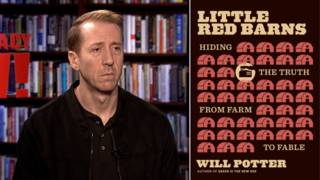

AMY GOODMAN: That was Wayne Hsiung of Direct Action Everywhere, DxE, at a pig farm in 2017. He and a fellow animal rights activist, Paul Picklesimer, were just acquitted by a jury Saturday night. Wayne Hsiung joins us now, co-founder of DxE, Direct Action Everywhere.

Hi, Wayne. Can you talk about the significance of the jury acquitting you both? You faced what? Five-and-a-half years in prison?

WAYNE HSIUNG: Amy, yeah, we initially faced 11 years in prison. One of the counts was dismissed. But it’s an incredible victory, and I’m still kind of reeling from it, because not only is this an incredibly conservative county that’s highly dependent on agriculture, but the rulings that were made in this court denied us the right to present most of the evidence your viewers just heard. So, the people on this jury were able to hear a very limited portion of the story. They knew we were there because we were concerned about animal welfare. They knew we felt that these animals needed medical care. And that was enough for them to exonerate us from any criminal responsibility for burglary and theft. And that’s a resounding victory not just for transparency and accountability in factory farms, but for the idea that animals are living beings and not just things to be thrown away into a garbage can.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Wayne, could you talk about Circle Four Farm? It’s one of the largest hog-producing facilities in the country, processes more than 1 million pigs a year. Smithfield Foods had promised to phase out the use of gestation crates. What are gestation crates? And did Smithfield Foods make good on their promise?

WAYNE HSIUNG: Juan, gestation crates, I like to call them basically metal tombs that a mother pig is forced to live in for five, six years of her life. But mother pigs are very large animals. They’re about 600, 700 pounds, so twice the size of an NFL lineman. And a gestation crate is a two-foot-by-seven-foot metal box, or metal tomb, that almost looks like a claw that grips the animal and holds them in place. So, about 14 square feet of space that a mother pig will live in for virtually her entire adult life. And this is to confine a large number of animals in a very small amount of space.

You’re right that Smithfield promised back in 2007 they’d be phasing these crates out, because when consumers found out about these devices — which have only been around for the past few decades, only since agriculture became industrialized — consumers have revolted against them. They don’t want these pigs confined in crates. And we did our investigation on Circle Four because it is the single largest facility owned by Smithfield in the United States. It’s systemically important. A huge amount of the pork production in the western United States comes from Circle Four. And when we walked into the facility in March of 2017, two months after they supposedly had phased out the use of these crates, we found thousands and thousands of mother pigs in these crates, and not a single mother pig outside of them.

AMY GOODMAN: Jim Monroe, Smithfield’s vice president of corporate affairs, said in a statement, “This verdict is very disappointing as it may encourage anyone opposed to raising animals for food to vandalize farms. Following this 2017 incident, we immediately launched an investigation and completed a third-party audit after learning of alleged mistreatment of animals on a company-owned hog farm in Milford, Utah. The audit results showed no findings of animal mistreatment.” Can you respond to that, Wayne, and also tell us about these baby piglets and how you went into the factory — they were less than a week old each, you named them Lily and Lizzie — and where you brought them?

WAYNE HSIUNG: Yeah. In regard to the first part of that statement, that this will encourage people to engage in vandalism, it won’t. It will encourage people to rescue dying and distressed animals. This is a completely nonviolent action. We walked in through an open door. We did not damage any property. We had no intent to harm anyone, not even the company itself. Our only intent was to give consumers the right to know what was happening inside these facilities and to give animals that are suffering the right to be rescued from torture.

With respect to the second part of the statement, that they had an independent audit done, I mean, first it’s worth pointing out that these independent audits are paid for by Smithfield. These are longtime contractors of Smithfield who basically do their bidding. But secondarily, in discovery in this case, we actually obtained a copy of this audit. Even their own in-house audit, paid for by Smithfield itself, found baby pigs piled up in gas chambers three deep. And their own auditor said, “This is unacceptable. You cannot pile up living, dying and sick animals three deep, squirming and trampling on top of each other, inside of a gas chamber.” Yeah, this is what they’re considering humane.

With respect to these two baby piglets, Lily and Lizzie were both in terrible condition. And I think one of the reasons the jury acquitted us is because while we were not able to present evidence of the general conditions at Smithfield and the promise they made about gestation crates, we were able to present evidence about these particular piglets, because they were, after all, subject of the so-called theft. And I think, honestly, when the jurors first saw Lizzie with her face covered in blood, scarring all across her face, because she was unable to access food from her mother, I could see in their faces they were horrified, and they wanted this to stop. And we’re seeing that across the nation. When people actually see especially an individual animal and feel the suffering of that individual animal and empathize with their story, they realize, “I don’t necessarily want to be part of the system. I want to do something else.”

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Wayne, could you talk about not only how some of these factory farms mistreat and basically torture these animals, but also how they deal with their workers, most of whom are immigrants?

WAYNE HSIUNG: Yeah. So, Smithfield has a long history of mistreatment of its own employees. Bob Herbert at The New York Times did a number of really good pieces in the early to mid-2000s about union-busting efforts at Smithfield. At some of their largest plants, they were not only preventing workers from unionizing, in illegal ways, they were actually physically assaulting their own employees. And this has been verified by the National Labor Relations Board. A federal court has reviewed some of the evidence and concluded there was intentional violence against their own workers merely for trying to get a living wage, to improve their working conditions. And slaughterhouses and factory farms are some of the most dangerous places to work in the world, because the same blades and gas chambers and devices that are used to harm animals can be used inadvertently to harm a human being.

But probably the most infamous incident in Smithfield’s history, which actually unfolded at the exact site where we did our investigation and open rescue, was an instance of human trafficking, where they were shipping people in from Asia, not paying them, threatening their families back at home. And Smithfield escaped almost all accountability for this incident. It was literally an incident of human slavery. It’s been widely reported in the media from the early to mid-2000s. And Smithfield escaped responsibility because, as with many corporations, they blamed a contractor. They blamed a subsidiary. They blamed someone else and said, “Oh, this isn’t our fault,” when this is a massive facility of hundreds of employees, supposedly well managed and supervised. They claim they care for the animals and their own workers with a lot of attention, yet they didn’t realize that there were people being trafficked in their own facility.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to thank you, Wayne Hsiung, for joining us. Wayne Hsiung is the head of Direct Action Everywhere, known as DxE, speaking to us from Utah, where he was involved with a direct action, a rescue of piglets five years ago. He and his colleague were just acquitted on Saturday night. They faced, oh, first 11 years, then five-and-a-half years each in prison.

Coming up, we talk to Frances Fox Piven, the legendary sociologist and political activist. She just turned 90 yesterday. Stay with us.

Media Options