“Freedom Dreams: Black Women and the Student Debt Crisis,” a new short documentary from The Intercept, profiles Black women educators and activists struggling under the weight of tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of dollars in student loan debt. It is directed by Astra Taylor and Erick Stoll, narrated by former Ohio state Senator Nina Turner, and was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. “A system where Black women do not have to be subject to crushing debt is a system that would benefit everyone,” says Shamell Bell, one of the women featured in the film.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Astra Taylor, I want to go to your new short documentary for The Intercept, Freedom Dreams: Black Women and the Student Debt Crisis, profiling Black women educators and activists struggling under the weight of tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of dollars in student loan debt. It begins with former Ohio state Senator Nina Turner.

NINA TURNER: Let me give my testimony, if I might, if I may, that I am a first-generation college graduate. And I tried to break the cycle of poverty in my family’s line. Everybody has a hope and a dream for better. And debt, because you decided to go and advance yourself through higher education, should not happen in this country, no how, no way.

PROTESTERS: Hey, hey! Ho, ho! Student debt has got to go!

NINA TURNER: Student debt punishes poor and working-class people for pursuing higher education, ensnarling individuals and entire communities in compounding interest and fees. Today, student debt is a nearly $2 trillion weight, crushing 45 million people, with women, and especially Black women, disproportionately burdened. Student debt is a trap, and it is also a teacher. Debt teaches us that education is a commodity, that we need to choose degrees and careers based on pay, that we are alone in our financial struggles, that we don’t deserve to be free.

MADDY CLIFFORD: I owe over $120,000 in debt. And I basically — I didn’t talk about it. And anytime I did, I automatically felt ashamed.

SHAH NOOR HUSSEIN: I am probably about $80,000 in debt. And up until recently, I was — I think my word was “shame,” too. But while you were talking about it, I was actually like, you know, it’s “regret.”

MADDY CLIFFORD: I decided to go to college because, like, I’m a nerd. I love education. I love school. And I thought to myself, “Well, it doesn’t matter how much it costs. Like, it’s going to pay off.”

ARIES JORDAN: Like, I had to go to school. I’m from a family of educators. They were like the first generation in their family, you know, in our family. So, it was like, you had the opportunity, you’re going to college.

SHAH NOOR HUSSEIN: I was really adamant on moving towards my career goals, and so I just, like, pushed myself into this master’s program without thinking, “How am I going to pay for it?”

NINA TURNER: A lack of intergenerational wealth and other structural inequities force women, and Black women in particular, to borrow at disproportionate rates. And wage discrimination makes it that much harder to escape. For every dollar white men make, Black women earn 61 cents — a lifetime loss of almost $1 million.

MADDY CLIFFORD: We’ve been, you know, told, working-class people, that as long as you get an education, then you will have job prospects, you’ll be able to take care of your family, you’ll be able to have a future. I really used to blame myself a lot, and I used to feel a lot of shame. And then I started to look at the policies, and I’m like, “Wait a second. Is it personal responsibility, or is it really bad policy?” And I realized it’s bad policy, straight up.

RICHELLE BROOKS: The inaccessibility to higher education is preventing us from being able to take care of our families. The inaccessibility to higher education is keeping us in poverty.

Student loan debt was never explained to me. There was never a person that sat down and said, “Hey, here’s how you’re going to pay for college.”

That means, over time, we’re growing further and further in debt due to these inequitable systems.

I originally borrowed $203,000, and that balance has since grown to $238,000. I loved being in the classroom, but teachers just do not make enough money to survive in L.A. Ended up with a master’s degree and then a doctorate, and then I became a principal, which is pretty much the highest position you can be at a school, and I’m still not making enough money to pay my student loan debt balance.

I feel stuck between a rock and a hard place when I’m talking to my students about their plans for their postsecondary education goals. I’m teaching them to navigate the system in a way that I wasn’t taught, but I’m still fearful for them. And there’s days that I’m just filled with regret.

That balance doesn’t leave. That $238,000 is there with me every second of every single day. You go work for these high-tech companies, you can make $250,000, $300,000 and not have to worry about how you’re going to pay back the debt. I could have done that. I am smart. I could have done that. But I took on this commitment to become an educator, and I’m being penalized for it.

MADDY CLIFFORD: Actually, the roots of the student debt crisis started in California. Yeah, it started around the time of like the ’60s and ’70s, when people were becoming really revolutionary. I mean, the Black Panthers were going to college. More women were going to college. And at the time, college was actually free in California.

NINA TURNER: In 1966, Ronald Reagan, the newly elected governor of California, burnished his image by attacking the antiwar and racial justice movements taking root on university campuses. He proposed rolling back California’s program of free public college and charging tuition. “Taxpayers,” Reagan said, “should not be subsidizing intellectual curiosity.”

GOV. RONALD REAGAN: We have been and are providing a premium service, an education superior to most and equal to the best. So far, those receiving this education have not been required to share in the cost.

RICHELLE BROOKS: When Black and Brown people started going to college in California, that’s when you see public education fall away. So the burden of paying for education was placed on families.

ARIES JORDAN: I feel like this is another way to block access to education. Our grandparents were coming off of integration. So we were running up in those schools, Black people, like we’re going to get our education. But now we still got this debt, though.

RICHELLE BROOKS: Anything less than full debt cancellation is a loss, especially for the most marginalized. How much debt do you have? You want to —

SHAMELL BELL: We gonna talk about this? OK, yeah, I’m not ashamed. So, let’s talk about it. I have $250K in student loan debt. I am a Ph.D., and I’m now working. And I told you I was working at Harvard. And I’m part-time. And I’m not going to be able to pay back $250K.

I’m differently abled, so it took me eight years to get out of my undergrad, because I wasn’t well. And so, the only path for me at that moment, which is I had to take a whole bunch of loans.

RICHELLE BROOKS: For me, personally, $230,000 worth of student loan debt means that I can’t purchase a home.

SHAMELL BELL: I was sold a myth in society that once I got my Ph.D., then I would be able to have upward mobility, that the access to generational wealth would open up for me.

Upward mobility, that is a misnomer. Is that the word?

RICHELLE BROOKS: Yeah, that works. That works.

SHAMELL BELL: Upward mobility.

RICHELLE BROOKS: It’s a lie.

SHAMELL BELL: That’s a lie! So, this idea of good debt and bad debt — you just brought up homes, that “good debt.” We don’t even have access.

RICHELLE BROOKS: We can’t even get there.

SHAMELL BELL: We can’t even get the good debt.

RICHELLE BROOKS: We can’t get the good debt.

SHAMELL BELL: We can sure get some bad debt real quick, though.

Debt impedes our ability to dream. And I see that in my students. I wanted to be the educator that told the truth and the educator that unlocked dreams.

If this system was no longer what we see right now, and we were able to not only imagine and envision something different, but we were actually able to embody it and do it, like, what does that look like?

So, a system where Black women do not have to be subject to crushing debt is a system that would benefit everyone.

AMY GOODMAN: An excerpt of The Intercept's short documentary Freedom Dreams: Black Women and the Student Debt Crisis, narrated by former Ohio state Senator Nina Turner, co-directed by Astra Taylor, who we're speaking to today, organizer with the Debt Collective. So, looking at a chart from the Department of Education, the percent of fourth-year undergraduate students aged 18 to 24 with student loan debt by race: African Americans, 90%; Latinos, 72%; whites, 66%; Asian Americans, 51%. Where do you go from here, after the partial debt forgiveness that President Biden issued by executive order yesterday, Astra?

ASTRA TAYLOR: We’re going to keep fighting. The Debt Collective has been sounding the alarm about student debt and organizing on the basis that our debts are actually a source of power when we get organized. Individually, they can overwhelm us, but when we come together, we can use our debts as leverage to demand change. And we have done that, stepping stone by stepping stone, beginning with our campaign with former Corinthian students. They were students who had been defrauded by the predatory for-profit chain. They launched a debt strike, coupled with a creative legal strategy. We just won them, earlier in the year, after seven long years, full automatic cancellation for over half a million people. We built on that. After they went on strike, students from ITT Tech and other predatory colleges, they just won $4 billion of cancellation. And then this announcement from President Biden that debt would be canceled for tens of millions of Americans. So, we’ve been building through strategy — through strategizing and through creating solidarity among debtors, not letting us be divided and conquered. And so, we’re going to keep doing that.

There’s actually a debt strike launching because they have extended the payment pause, the payment moratorium, until January 1st. So, thousands of people are saying, “We can’t pay. We’re never going to pay. This cannot be the final extension of the payment pause.” We have a growing number of debtors joining the movement, including a growing number of older debtors who are suffering under these enormous six-figure burdens. Older people are often left out of the debate. It’s actually the fastest-growing demographic of student debtors. So, we’ve launched a “50 Over 50” debt strike, that is already in the hundreds now, just in a matter of days. So, the flight’s going to keep going. And we’re going to continue also our work on medical debt, back rent and bail debt, until we can win a society where people are not forced into debt just to survive.

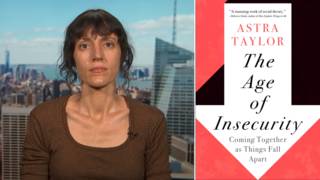

AMY GOODMAN: Astra Taylor, we want to thank you for being with us, organizer with the Debt Collective. We will link to your new short documentary, Freedom Dreams: Black Women and the Student Debt Crisis.

Next up, to Oklahoma, where the state is planning to execute a person a month for the next two years, starting today. Stay with us.

Media Options