Guests

- Ariel DorfmanChilean American author, playwright and poet, as well as a professor emeritus of literature at Duke University.

- Javiera Manziactivist with Chile’s largest feminist advocacy group, Coordinadora Feminista 8M.

Voters in Chile have rejected a new constitution that would have replaced the country’s Pinochet-era constitution and expanded rights for Indigenous peoples and abortion seekers, guaranteed universal healthcare and addressed the climate crisis. The new charter was rejected with 62% voting “no,” and President Gabriel Boric has now vowed to continue efforts to rewrite the charter. Corporations and outside interests overwhelmingly outspent supporters of a constitution that “does not put extraction as the center of Chile’s development but people as the center of its development,” says Chilean American author Ariel Dorfman. The rejection of the constitution does not mean a rejection of its principles but the hegemony of the neoliberal status quo and a rampant disinformation campaign, says Chilean feminist Javiera Manzi, who joins us from Santiago and worked with delegates to draft the new charter.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González, as we turn to Chile, where on Sunday voters rejected a new constitution that would have replaced the one imposed by the military dictator General Augusto Pinochet, who seized power 49 years ago in a U.S.-backed military coup, with one of the most progressive charters in the world. Results show about 62% of Chileans voted “no,” while 38% voted in favor of the new constitution.

The proposed charter grew out of anti-austerity demonstrations in 2019. It was the first in the world to be written by an equal number of male and female delegates, and included on new rights for Indigenous people, legalized abortion, mandated universal healthcare and new commitments to address the climate crisis. It also strengthened regulations on mining, prompting an editorial from The Washington Post editorial board that opposed the constitution based in part on how it could make it harder for the United States to acquire Chilean lithium used for batteries in laptops and cars.

Chile’s President Gabriel Boric has been a major supporter of the new constitution since he was elected in December and sworn in this past March as the youngest president in the country’s history. President Boric spoke Sunday in Santiago after the results showed the proposed new charter had been rejected, and said he wants to restart the process in order to meet a 2020 mandate.

PRESIDENT GABRIEL BORIC: [translated] As the president of the republic, it is with great humility that I take this message and make it my own. We have to listen to the voice of the people, not just today, but the last intense years we’ve lived through. Let us not forget why we have come this far. That malaise is still latent, and we cannot ignore it. Those who have historically supported this transformation process must also be self-critical of our actions. Chileans have demanded a new opportunity to meet, and we must live up to this call.

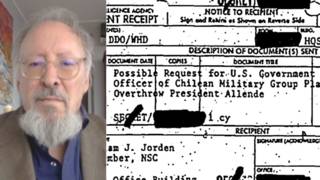

AMY GOODMAN: Sunday’s vote came on the anniversary of the September 4th, 1970, election of the socialist Salvador Allende as Chile’s president, before he was overthrown in the 1973 U.S.-backed military coup that installed General Augusto Pinochet as dictator and left the country with the constitution it still uses today.

For more, we’re joined by two guests. Ariel Dorfman is with us, Chilean American author, human rights defender, playwright, poet who was cultural and press adviser to President Allende’s chief of staff during the last months of his presidency in 1973, right before Allende died in the palace September 11th, 1973. Ariel Dorfman is the author of a number of books, including, most recently, Voices from the Other Side of Death. And in Santiago, Chile, we’re joined by Javiera Manzi. She’s a feminist who played a role in the drafting of the proposed new constitution with the delegates.

Welcome both to Democracy Now! Ariel Dorfman, if we can start with you? The significance of the charter, and the charter’s defeat?

ARIEL DORFMAN: This was an extraordinary Magna Carta, both because of its origins, in a popular protest, because it was drafted by people who looked like Chile itself, not sort of elite experts who behind closed walls were constantly deciding what others would be ruled by. And it was, as you mentioned, you know, incredibly ecological, the most advanced in the world. It extended democracy in participatory forms in all levels. It legalized — not only legalized abortion but — you know, when I read the constitution, and I’ve read it several times, the one that has just been rejected, what calls attention to myself is the extraordinary tenderness with which it’s been composed and written. It speaks about the glaciers. It speaks about the air. It speaks about the children, over and over again the children. It speaks about the caretakers at home. It speaks about the animals. It speaks about the dogs. It speaks about everything vulnerable that needs to be taken care of. And, of course, it includes there, for the first time, those who have been invisible and exspoliated constantly by the major powers in Chile: the Indigenous populations. It is also an extraordinarily feminist constitution. And I just could go on and on and on. It had 388 articles, perhaps too many.

But its rejection is a very significant defeat. However, I am not entirely pessimistic about what the future will bring. And I could explain further, if you feel that I need to do so. Some of the reasons why this happened, because we should not forget that 62% of the people in the largest election, 13 million voters, much more than ever before in the nation’s history, did reject this proposal. And they did not, however, because 80% of the people decided previously that there has to be a new constitution. So we will have a new constitution. The question is if we are now under the veto power at the right-wing people in Congress, who will try to restrict as many of these rights as possible.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Javiera Manzi, I wanted to ask you — you were part of helping to draft this new constitutional proposal with constituent Alondra Carrillo. What’s your reaction to seeing it defeated? And why do you think that occurred? Some critics say that the writers attempted to go too far ahead of where the Chilean people were at this point. Your response?

JAVIERA MANZI: Yes. Good morning. I think that, for us, the first thing we have to answer is: What was in stake in this election, in this referendum? What did the people actually reject when they went to vote rejection? Was that at stake the content of this draft, or was there something else?

For us — I was part of the coordination of the social movements committee for the campaign for the approval, and yesterday we made a declaration where we said that this was, of course, a defeat, but an electoral defeat, not the defeat of a project. And that, for us, is what is at stake today, and how we understand and interpret this result, because, of course, for the far right, this is being said to be the defeat of a project, the defeat of a cycle of social mobilization. And for us, it’s important to say that this was a campaign that we did in an extreme context of inequality, the terms of how we had to campaign in a context where every single social media, every single — the TV set in the house of every person in Chile was always talking about not only fake news but about a context — content that wasn’t even there, the idea that people would have no housing, for instance, or that private property was going — was at stake or was in a menace. It was a very widespread idea.

And so, we had to be — made a campaign in a context that it was very difficult to defeat that commonsense idea that was starting to spread out and in a context that this was the first time since 2012 that we had a mandatory vote. So there was like — there was a whole part of the society in Chile that went to vote for the first time in ages. So, it is very important for us to say, and these days are going to be very important to try to understand, interpret and to say what’s at stake in the future days and the future of a possible constituent process.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Ariel Dorfman, I wanted to ask you about this issue of the disinformation campaign that was launched within Chile, and also some of the propaganda outside of Chile, as Amy mentioned, The Washington Post editorial saying that, quote, “Lithium is a key input in batteries that run millions of laptops and upon which the United States is basing its electrified automotive future. Chile sits atop the world’s largest lithium reserves.” You remember when American companies were concerned — more concerned with Chile’s copper back in the days of Allende and how Chile has always been seen as a resource for the Western imperialist countries.

ARIEL DORFMAN: Yes. First, the disinformation campaign, the fake news. The official official people in charge of the election have said that 89% of the funding for the rechazo, the people who rejected, was versus 11% of the money spent by the approval people, right? So that’s four to one. You have to imagine how unequal, as we just heard our colleague in Chile say, right? So, that fake information was very cunningly used, as was used problems that the constituent assembly itself had, certain extravagances, certain scandals that happened, but always trying to create a fake sense of what was in the constitution. I think many people didn’t even read what was in the constitution; they simply had an impression of it.

In relation to this, what’s interesting is that just as in the case of Allende, this is an anti-extractive constitution, meaning it does not put extraction as the center of Chile’s development, but people as the center of its development. The richness of Chile is its people. And we have the lithium, of course. We’ve got lots of lithium as before we had the copper. We still have that copper. But the important thing here is, is that one of the forms of the constitution speaks about the fact that we have sovereignty over what is in our subsuelo, in our minerals, right? And, of course, people are very worried about that outside, despite the fact, of course, that the constitution itself does not say that we will stop foreign investments or things like that. We will simply have control of it, as in the case when Allende nationalized copper — by the way, with the unanimity of Congress.

So, of course, outside, The Washington Post, which I found strange, really, to tell you the truth, The Wall Street Journal, which I didn’t find so strange, The Economist, which I didn’t find so strange, lots of people from the outside kept on speaking about these things, and these were reverberated in Chile, right? Whereas when somebody like Pedro Pascal, for instance, would tweet about that, or the International Socialist groups would speak about that, or Thomas Piketty would speak about how wonderful, or constitutional experts all around the world saying this constitution in fact extended rights, it did not restrict rights, all that was shouted down, was shut down, was forgotten, right?

So, there is a campaign outside Chile. It’s not unanimous, either, because there have been relatively good things — there’s been a very good op-ed in The New York Times, as well. And I myself was able to write something in the Los Angeles Times, and tomorrow I have something in The Guardian. So, it’s not as if we’re completely muted in that sense. But there is a worry among the — let us call it the oligarchs of the world, those who control the riches of the world, and who are the equivalent of those who control the riches in Chile, right? I mean, the amount of money spent by the corporations in Chile is simply shameful.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to just — when you said it was surprising in The Washington Post, Common Dreams, Brett Wilkins, had an interesting piece where he said Washington Post “owner Jeff Bezos and other billionaires including Bill Gates this year invested nearly $200 million in KoBold Metals, which according to Mining.com [quote] 'is on a global search for key battery metals cobalt, lithium and nickel, as well as copper, which is key to the green energy transition.'” Might help explain something there. But I wanted to end with Javiera Manzi, the feminist activist, who played a key role in the protests in Chile and then working with others in the drafting of Chile’s proposed new constitution. Where you go from here, Javiera?

JAVIERA MANZI: Well, we must say it’s a very hard time for us in Chile, and we have to start from there. The result is not only an electoral defeat in the sense that the constitution was not approved, but it also shows the extent of the hegemony of neoliberal common sense and how there’s a very major — we have to — a challenge to overcome this moment, not only in terms of the constituent process but, of course, in terms of how the far right has gained a lot of power and this ability around this campaign.

For us, it’s important on what is at stake in this moment is to try to overcome, to create a new alternative politically and visible feminist alternative, because I think that in this moment, this very moment, including feminism, is at stake. We need to overcome, as well, because we know that what was rejected is not the context — is not the content of the constitution. It’s not the recognition of domestic labor. It’s not the recognition of a right to decide an abortion and sexual justice. It’s not the recognition of housing, health, labor, rights. But it’s something else. And it’s the idea that we have to change and transform the structure, the neoliberal and authoritarian structure of Chile that will continue to govern us.

So, for us, it’s very important to say that social movement, grassroots organization and the feminist movement as a whole, we are now taking a moment to think, to analyze these results and to organize ourselves, because it’s going to be a very hard moment. We are going to live the crisis, this economic — global economic crisis in a context of a government that will have to overcome these results and that will have to rearrange its political forms and alliances. And we need not it not to be in terms of how they’re going to give more space for a neoliberal answer to this moment. So we are going to keep on fighting for a new constituent process, and we’re going to keep on fighting against the advance of the far right in Chile.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, we will continue to cover it. I wanted to ask Ariel if you could close this segment with a poem from your latest book?

ARIEL DORFMAN: Yes. This is about the disappeared, because it turns out that we are fighting also for the disappeared, the desaparecidos. We’re fighting for all the dead who died so that we could have a different Chile. It’s called “Last Will and Testament.”

When they tell you

I’m not a prisoner

don’t believe them.

They’ll have to admit it

some day.

When they tell you

they released me

don’t believe them.

They’ll have to admit

it’s a lie

some day.

When they tell you

I’m in France

don’t believe them.

Don’t believe them when they show you

my false I.D.

don’t believe them.

Don’t believe them when they show you

the photo of my body,

don’t believe them.

Don’t believe them when they tell you

the moon is the moon,

if they tell you the moon is the moon,

if they tell you this is my voice on tape,

that this is my signature on a confession,

if they say a tree is a tree

don’t believe them,

don’t believe

anything they tell you

anything they swear to

anything they show you,

don’t believe them.

And finally

when

that day

comes

when they ask you

to identify the body

and you see me

and a voice says

we killed him

the poor bastard died

he’s dead,

when they tell you

that I am

completely absolutely definitely

dead

don’t believe them

don’t believe them

don’t believe them

no les creas

no les creas

no les creas

Don’t believe them when they say there will be new constitution. Don’t believe them when they say that the people of Chile will stop struggling for justice and social equality. Thank you so much.

AMY GOODMAN: Ariel Dorfman, Chilean American activist and author, reading from his most recent collection of poems, Voices from the Other Side of Death. And Javiera Manzi, feminist leader in Chile who helped the delegates in drafting Chile’s proposed new constitution.

Next up, we remember author Barbara Ehrenreich. Stay with us.

Media Options