Former U.S. secretary of state and national security adviser Henry Kissinger has died at the age of 100. He leaves behind a legacy of American statecraft that brought war, covert intervention and mass atrocities to Southeast Asia, South Asia and South America. “Few people have had a hand in so much death and destruction,” says our guest, human rights attorney and war crimes prosecutor Reed Brody. By some accounts, Kissinger was responsible for the deaths of at least 3 million people. We focus today on Kissinger’s actions in Cambodia, Bangladesh (previously East Pakistan) and East Timor, where, Brody argues, Kissinger ordered and oversaw U.S. actions that would make him “liable for war crimes.” Brody also discusses the International Criminal Court and the ongoing war in Gaza.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman.

We end today’s show looking more at the death of Henry Kissinger, remembered by some as a leading diplomat, but by many others as a war criminal for his actions in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Pakistan, Chile, Argentina, East Timor and other countries. By some accounts, Kissinger was responsible for the deaths of at least 3 million people. Kissinger served as U.S. secretary of state and national security adviser under Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.

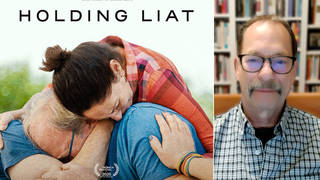

We’re joined now by Reed Brody, human rights attorney, war crimes prosecutor, author of To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré. In June, Reed wrote an article for Just Security titled “Is Henry Kissinger a War Criminal?”

Well, why don’t you answer that question, Reed, and talk about what should happen at this point? Now at the age of 100, Henry Kissinger is dead.

REED BRODY: Thank you, Amy.

Well, as you’ve said, I mean, few people have had a hand in so much death and destruction in different parts of the world than Henry Kissinger. But what I tried to do in this article was look at specific instances of Henry Kissinger’s action and whether he could be accused of war crimes. In fact, after the arrest of General Pinochet, Michael Ratner and I were teaching a class at Columbia Law School on the Pinochet precedent. We asked students to look at different incidents. And three in particular suggest that Henry Kissinger could have been accused of war crimes. One is Cambodia, the other is Pakistan, and the other, which you’ve talked about a lot on your show, is East Timor. I know we have little time.

In Cambodia, we know that Henry Kissinger chose bombing targets, that he ordered that anything that moves be bombed. And that, in essence, is ordering a war crime, ordering that even civilian targets be attacked.

In the case of East Pakistan, 1971, Pakistan was two separate countries. There was an election. An independence leader won in East Pakistan, but West Pakistan, Ayub Khan, would have nothing to do with it. And they started attacking civilians in East Pakistan, raping tens of thousands of women, hundreds of thousands killed. The American consul in East Pakistan wrote a memo to Henry Kissinger saying, “We are participating in a genocide. We have to stop.” The U.S. ambassador to India, Kenneth Keating — sorry, yeah, Keating — the former senator of New York, told Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon, “We are participating in a genocide.” Kissinger had the author of the memo fired. He called Keating a traitor. And not only did they not restrain Pakistan, who was receiving 80% of its military assistance from the United States, they actually organized the transfer of American weapons from Iran, from Jordan, to Pakistan as the bloodshed continued. So that makes Henry Kissinger liable for aiding and abetting the slaughter that was carried out there.

A very similar situation that you know well, Amy, East Timor. Not only did Henry Kissinger and Gerald Ford give the green light to the invasion of East Timor, but as the casualties mounted, as hundreds of thousands of Timorese were dying, the United States, which had a donor-client, as Henry Kissinger called it, relationship with East Timor, that was supplying 90% of — excuse me, of Indonesia — 90% of Indonesia’s military, gave additional assistance.

And so, these situations — Timor, East Pakistan — it’s as if you’re in an ammunition store, and the guy is out there on a shooting spree, and he comes back to get more ammunition, and you give it to him. These things make Henry Kissinger, I believe, liable for war crimes.

AMY GOODMAN: Cambodia and Laos, how many people died? And what exactly was Henry Kissinger’s role as secretary of state under President Nixon?

REED BRODY: Well, we don’t actually know how many people died. We do know that as a result of Henry Kissinger’s order to bomb anything that moves, that the bombing of civilian areas, the bombing of the area near the border between Cambodia and Vietnam, were tripled. And, of course, the tragedy of this is that the bombings and the destruction of that part of Cambodia drove many Cambodians into the arms of the Khmer Rouge and led to the Khmer Rouge takeover in Cambodia. Similarly in Laos, the secret bombing. Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon expanded the Vietnam War, and it began with the secret bombing of Cambodia and the secret bombing of Laos, that resulted in hundreds of thousands — I don’t know the number — of dead, including mostly civilian dead.

AMY GOODMAN: So, when you talk about international human rights and war crimes, what are the avenues to hold a public official accountable? Why wasn’t Henry Kissinger held accountable, tried for war crimes — where would he be tried for war crimes — when he was alive?

REED BRODY: Well, that’s a very important question. Of course, the modern era, let’s say, of international criminal justice began 25 years ago, 1998, with the creation of the International Criminal Court, on the one hand, and the arrest of General Pinochet in London, on the other hand; an international tribunal, on the one hand, and national courts using their universal jurisdiction to prosecute individuals, on the other hand. And that’s actually when we began to look seriously at the alleged crimes of Henry Kissinger.

Now, what’s interesting is that all of these things predated. I mean, Henry Kissinger’s involvement in Cambodia, in Laos, in East Timor, in Pakistan predated that modern era. But what’s really interesting is that in each of the instances I’m talking about — Cambodia, East Timor, Pakistan — there actually were tribunals set up afterwards to look at war crimes. So, as you know, in Cambodia, the United Nations. after the Khmer Rouge fell, created an international tribunal to prosecute the crimes committed in Cambodia. But, of course, the U.S., which backed the tribunal, insisted that the jurisdiction of that tribunal only cover the Khmer Rouge period, not go back to the period of U.S. bombings. And, in fact, every time there was a tug of war between Hun Sen and the United States over the tribunal, which Hun Sen tried to — in fact, did control and made sure none of his people were involved, were investigated — he would threaten, said, “You know, we could go back and look at what you guys did.” And so, you had a tribunal for Cambodia. It just didn’t include what the U.S. had done.

Same thing in Pakistan. There was eventually a tribunal established in East Pakistan, or in Bangladesh, as it’s called now, to look at crimes committed during that genocide. But it, too, did not take jurisdiction over those people who were not living in the country.

And finally, in East Timor, at the very end, after East Timor gains its independence and a reckoning began into who was responsible for what — and, of course, the East Timorese Truth Commission specifically talked about the United States’s role in creating the horrors and in supporting the Indonesian massacres — the East Timor tribunal also chose, in fact, not to go back and look at the U.S. period.

So, very rarely — I mean, it was very unusual in the pre-1998 world, in the pre-International Criminal Court world, to have tribunals looking at past actions. In each of these three cases, you did have tribunals, but in each of these three cases, there was a choice made not to go back and look at what the United States, under Henry Kissinger, had done.

AMY GOODMAN: And why was that? Was the U.S. behind that, putting pressure on these countries? And also talk about the double standard. I mean, when you look at, for example, the International Criminal Court, how often it is not leaders from countries like the United States who are put in the dock?

REED BRODY: Well, of course, Amy, in the world I operate in of international justice, double standards is the main — the main obstacle. It’s the main sticking point. It’s very, I mean, still — it’s never easy to bring people to justice, even Third World dictators, but it is sometimes possible. But international justice has always fallen flat when it comes to dealing with powerful Western interests. We see at the International Criminal Court, for instance — of course, the International Criminal Court, it should be pointed out, in 21 years, and at the cost of $2 billion, has never actually sustained the atrocity conviction of any state official, not just Western, any state official, at any level, anywhere in the world. The only five final convictions at the ICC were five African rebels. But there have been attempts by the ICC to prosecute leaders, all in Africa, in fact. And, of course, now, more recently, we have the indictment of Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia.

And I think, you know, many people are contrasting — I mean, I would contrast — the international justice response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Russian war crimes in Ukraine — in that case, we saw a very vigorous and heartwarming response internationally. The prosecutor of the ICC, Karim Khan, immediately went to and made several visits to Ukraine, a country that he called a crime scene. Forty-one Western countries gave the ICC authority, jurisdiction or triggered an investigation. Karim Khan raised millions of dollars in extrabudgetary funds to address the situation in Ukraine, and within a year, of course, indicted Vladimir Putin. This is as it should be. This is exactly what the International Criminal Court is there for.

The contrast is, you know, in Palestine. As we talked about on your show once, for 15 years the Palestinian complaints at the ICC have been given this slow walk by the prosecutor, first several years — by three prosecutors — by the first prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, who spent several years evaluating whether or not Palestine was a state — was a state — before finally punting the issue. Then, after the General Assembly of the U.N. determined and recognized Palestine as an observer state, there was a lot of pressure on Palestine not to ratify the ICC statute. Friends of the ICC, countries like Britain, and, of course, even the United States put pressure on the Palestinian Authority not to ratify the ICC treaty, because they didn’t want to inject justice which could interfere with the peace process, which of course was not going on. But Palestine did ratify the ICC treaty and filed a request for an investigation. And then the second prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, spent five years looking at whether there — crimes had been committed, finally determined, just as she was about to leave office, that there was sufficient evidence to believe that crimes may have been committed, crimes including illegal settlements, war crimes on both sides, and gave it to this prosecutor. This prosecutor, Karim Khan, has had those issues sitting on his desk for two years. He had one person in his office investigating that case. And it wasn’t until October 7th and, you know, what has happened since that the ICC has kind of sprung into action. But the question has always been, you know: Why was Palestine treated differently? Why were the complaints, why were the issues there treated differently, until now?

AMY GOODMAN: Reed, I wanted to go to the chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, Karim Khan, who did visit Israel and, apparently, the West Bank Thursday at the request of Israeli survivors and the families of victims of the October 7th Hamas attack on Israel. Khan also visited places, as I said, in the West Bank. This is Karim Khan speaking at a news conference in Egypt last month.

KARIM KHAN: Too many are dying, and too many are being injured. And it’s alarming to see the bodies of young children, that could be our own children, being dragged, baked in dust, still, silent, motionless, because they’re dead. … In this regard, I have to say that Israel has clear obligations in relation to its war with Hamas, not just moral obligations, but legal obligations, to comply with the laws of armed conflict.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s Karim Khan speaking just a few weeks ago, the international war crimes prosecutor, the international — the ICC war crimes prosecutor. Can you talk about what he’s doing in Israel and the West Bank? And did he go to Gaza?

REED BRODY: Thank you. Well, the speech that you quoted, that you clipped of, probably the strongest speech an ICC prosecutor has ever directed towards Israel. I mean, he even talked about bombing decisions. And he said, you know, Israel has sophisticated legal officers who are choosing these targets, and, as he said, they will be under no misapprehension as to what the rules of war are. And this was — actually, it was a very powerful statement.

The question, of course, is: What is going to — is, you know: What is going to happen next? I mean, is he going to follow up these statements with action? Is he going to take up the cases that had been sitting on his desk for years, including settlements? Will he be allowed in?

Now, today, as we speak, he has visited Israel. This is extraordinary, the first time that an ICC prosecutor has been allowed into Israel. Israel does not recognize that the International Criminal Court has jurisdiction. Israel has not ratified the treaty. The position of Israel and the United States is that the ICC does not have the authority to investigate the crimes, or the alleged crimes, committed by nationals of a non-State Party, like Israel. Of course, they forget that when it comes to non-State Parties like Russia for crimes in Ukraine. But the position here has always been Israel does not recognize the court.

Now, for the prosecutor to say that he has visited Israel on the request of families of October 7th, yeah, I do believe that they invited him, but, of course, Israel would have to accept that he come in. You just don’t get invitations from private parties for an ICC prosecutor. Palestinian families have been inviting him for years. Now, he’s gone to Israel. He says that he is visiting with families of October 7th. He says he’s visiting senior officials in Ramallah. He doesn’t say that he’s going to Gaza. He doesn’t say why he isn’t going to Gaza. He doesn’t say Israel has allowed me to do this, but not that. There’s no indication that he is visiting Palestinian victims. There’s no indication that he is visiting illegal Israeli settlements. And he says, even in the announcement, this is not an investigation. This is a visit to open a dialogue and to hear from people. But it would be good if he would hear from all sides.

But, most importantly, the question is, you know: What can he do now? Now, I think there are two broad areas. First is — are all the things that were on his desk before. Settlements, for instance. It is illegal, it is a war crime, to occupy a territory and to move your people in. So, Israeli settlements are war crimes. Now, this is not something that you even need to go on the ground, really, to investigate. You can — the same way that the prosecutor of Karim Khan indicted Vladimir Putin for the taking of Ukrainian children. That was because Putin was — his fingerprints were all over it. It was a state policy. You didn’t need to go in and talk to the individual children. Same thing with settlements. This is a policy. You don’t need to be on the ground in order to move that kind of an investigation. So, there are the crimes that have been sitting on the desk of the prosecutor.

Then we have the bombings and — well, then we have Hamas’s crimes of October 7th and the Israeli bombings and the Israeli campaign now. These are, of course, much more difficult, because they’re actual heat-of-action things. You need to get on the ground, or it would be better to get on the ground. I mean, Hamas’s crimes are filmed. I mean, it’s pretty clear that, you know, there was cruelty, there was sadism, there were crimes being committed. But it’s, of course, important to go up. What were the orders? You know, was this cruelty, was this sadism, was this attack of civilians directed? Who directed it? Who might be responsible? Same thing in what’s going on in Gaza at the moment. I mean, the catastrophic situation, the tens of — I mean, the 15,000 civilian deaths, the attacks on hospitals, the attacks on ambulances, these are clearly — I mean, we can see the catastrophe on the ground.

The question — and your guest, Yuval Abraham, was very important, what he said, because he talked to people on the Israeli side. You know, the accusation here is that Israel is committing war crimes by attacking civilians or by disproportionately attacking civilian targets or by not discriminating between civilian targets and military targets. These are difficult things, by their nature, to actually prove. You have the result, and a lot can certainly be inferred from the very results and things, but you also want to know: What was the intention? And what Yuval Abraham was showing on your show was that there appears to be a conscious decision to loosen the rules to accept a larger number of civilian casualties than the laws of war would permit. But these are things that no serious prosecutor is going to, you know, today or tomorrow, give an indictment. These are things that are going to require very serious evaluation, not only of what’s on the ground, but what the Israeli military and their lawyers chose to do.

But, you know, now, hopefully, hopefully, we’re going to see action by the ICC. Hopefully, the ICC, which was so active in moving forward in Ukraine, will have the same intensity and will take on new staff, perhaps, and ask for a reasonable budget, in order, you know, to hold Israeli and Hamas officers to account.

AMY GOODMAN: Reed Brody, we want to thank you so much for being with us, human rights attorney, war crimes prosecutor. We’ll link to your article, “Is Henry Kissinger a War Criminal?” also his book, To Catch a Dictator. This is Democracy Now! For Part 1 of our discussion, go to democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options