Guests

- E. Patrick Johnsondean of the School of Communication at Northwestern University.

- Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylorprofessor of African American studies at Northwestern University.

- Khalil Gibran Muhammadprofessor of history, race and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School.

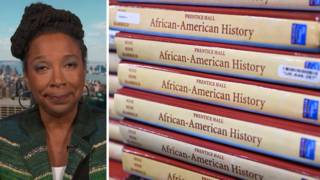

We host a roundtable with three leading Black scholars about the College Board’s decision to revise its curriculum for an Advanced Placement course in African American studies after criticism from Republicans like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. The revised curriculum removes Black Lives Matter, slavery reparations and queer theory as required topics, while it adds a section on Black conservatism. The College Board, the nonprofit organization that administers Advanced Placement courses across the country, denies that it buckled to political pressure. “Florida is a laboratory of fascism at this point,” says Khalil Gibran Muhammad, professor of history, race and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. We also speak with two scholars whose writings are among those purged from the revised curriculum: Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, professor of African American studies at Northwestern University, and E. Patrick Johnson, dean of Northwestern’s School of Communication and a pioneer in the formation of Black sexuality studies as a field of scholarship.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

We begin today’s show looking at the controversy surrounding the College Board’s decision to revise its curriculum for an Advanced Placement African American studies course. The revised curriculum removes Black Lives Matter, slavery reparations and queer theory as required topics, and it adds a section on Black conservatism. Many prominent authors and academics have also been removed from the AP curriculum, including James Baldwin, Frantz Fanon, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, June Jordan, Angela Davis, Alice Walker, Manning Marable, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Michelle Alexander, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Barbara Ransby, Roderick Ferguson and two of our guests today: E. Patrick Johnson and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. The new curriculum was released Wednesday, on the first day of Black History Month.

This all comes just weeks after Florida’s Republican Governor Ron DeSantis threatened to ban the AP Black studies course in Florida schools, and Florida’s Education Department said the course, quote, “lacks educational value.” Florida had raised concern about six points in the curriculum: Black queer studies, intersectionality, Movement for Black Lives, Black feminist literary thought, the reparations movement and Black struggle in the 21st century. While several of those topics have been removed as required parts of the new AP curriculum, the College Board maintains the final decisions to revise the curriculum were made in December, before Governor DeSantis said he was banning the class.

UCLA professor Robin D. G. Kelley, whose writings were also removed from the required curriculum, said, “This is deeper than an AP course. This is about eliminating any discussion that might be critical of the United States of America, which is a dangerous thing for democracy,” he said.

We’re joined now by a roundtable of guests. Two of them are professors whose work has been removed from the required curriculum.

In Greenville, South Carolina, E. Patrick Johnson joins us. He’s dean of the School of Communication at Northwestern University in Chicago and a pioneer in the formation of Black sexuality studies as a field of scholarship. His most recent book is Honeypot: Black Southern Women Who Love Women.

In Chicago, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor joins us. She’s professor of African American studies at Northwestern University, as well, a contributing writer at The New Yorker magazine and editor of the book How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective.

And Khalil Gibran Muhammad is with us, professor of history, race and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, author of The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America.

We welcome you all to Democracy Now! And we’re going to begin in South Carolina with Dean E. Patrick Johnson. You’re one of the banned. Can you respond to — this is a whole controversy. The College Board attacked The New York Times for saying that they removed these certain sections from the required AP course in response to Governor DeSantis. They’re not disputing, the College Board, that they removed these sections, but they’re saying they did it before DeSantis made his final comments on this issue. What is known is that the College Board made their — revealed the curriculum on the first day of Black History Month. Talk about what’s happening here.

E. PATRICK JOHNSON: Well, there’s so much to cover. You know, in response to the removal of my name, it’s a great list to be on, because of the wonderful thinkers that are included. And I also thought it was ironic that the fact that we’ve been removed means, actually, in some ways, more students will have access, because now people are doing searches for our work. So, that’s the irony in all of this.

I can’t speak to the College Board’s motivations or their process, but what I can say is everyone is clear that African American history is being used as a political pawn for the governor’s own ascension, his own aspirations to become president. This is a movement to gin up his supporters and the conservative movement. And most of us, you know, realize this, and so I’m not surprised by any of this. But it just means that we have to be steadfast. We have to keep at it and make sure that the students who would have otherwise been able to access our work can still access it in many other ways.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to Republican Governor Ron DeSantis in Florida telling reporters why he opposed the original AP African American studies course.

GOV. RON DESANTIS: This course on Black history, what are one — what’s one of the lessons about? Queer theory. Now, who would say that an important part of Black history is queer theory? That is somebody pushing an agenda on our kids. And so, when you look to see they have stuff about intersectionality, abolishing prisons, that’s a political agenda.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Dean Patrick Johnson, your response?

E. PATRICK JOHNSON: Ron DeSantis has no standing about what should and should not be a part of African American history. He’s not a scholar of African American history, and he himself is not African American. So, why should he have any role in what should and should not be included? And anything that — if anything lacks educational value, it’s the governor.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to your student, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, as a graduate student, now also a professor, a professor now at Northwestern University of African American studies, one of the canceled, as well. Professor Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, your response to this controversy, and what students will learn all over this country? It’s not just limited to Florida. There are laws being passed or being weighed in many states around the country.

KEEANGA-YAMAHTTA TAYLOR: Yeah. Thanks, Amy.

I want to talk about that, but I want to begin with your question about the College Board and their motivations, because I think it is believable that they had a piloted course that was being circulated among many schools, dozens of schools — I think it’s 60 schools around the country. It’s totally believable that, through that process, they decided that things needed to be removed from the course, that it needed to be revised in some way, that it needed to be tightened up. That is the purpose of having a pilot in the first place.

But what is not believable is that the political atmosphere had no bearing on their decisions about what to revise and the ways in which they revised it. And I say that because part of the — this has been — the development of this course has been in process for a decade. However, Trevor Packer, who is the head of AP within the College Board, told Time magazine last fall that the events surrounding the murder of George Floyd reinvigorated his desire to get this course accomplished. And so, it is hard to believe that given the circumstances around George Floyd and the historic demonstrations that came in the wake of that murder, the decision to excise any reference to contemporary Black America, to the Black Lives Matter movement is just coincidence, is unbelievable.

And so, the changes to the curriculum did not have to be directly related to the words of Ron DeSantis. The political writing has been on the wall, both in terms of the unfounded attacks on critical race theory, the derision of The 1619 Project, which is where much of this began, The 1619 Project being banned in states across the country, the mere mention of critical race theory being banned in states across the country. And so, at the College Board, you only needed to be a thinking person to realize that if we don’t change significant parts of this curriculum and weed out the radical writers, then, you know, we are probably are asking for trouble. So, their explanation that this is just part of the process and it has nothing to do with the political environment is completely unbelievable.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you to respond to David Coleman, the CEO of the College Board, defending their decision on CBS.

DAVID COLEMAN: We at the College Board don’t really look to the statements of politicians, but we do look to the record of history. So, when we revised the course, there were only two things we went to. We went to what Brandi described, which is feedback from teachers and students, as well as 300 professors who have been involved in building the course, and we went back to principles that have guided AP for a long time and served us well.

AMY GOODMAN: Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, your response?

KEEANGA-YAMAHTTA TAYLOR: Again, I do think that they were engaged in a process that went from a piloted course to a revised course. But even looking at history, some of this is completely nonsensical — the fact that in the unit on civil rights and Black power, that they have reduced the Black power movement to the life of Malcolm X, who was killed in 1965, before, really, the heyday of the Black insurgency in the late 1960s took place. And why is that important? Because from 1963, really, through 1968 — in Elizabeth Hinton’s book called America on Fire, which shows an even longer history of Black rebellion and uprising in the United States — is the context within which Black studies was born. Black studies as an academic field, as a discipline, emerges out of the rebellions of the 1960s. It is Black students demanding that their lives, that their history, that a curriculum be developed around the experiences of Black people, around an understanding of racism in the United States, around an understanding of the kind of core hypocrisy of the United States proclaiming itself to be a just democracy while treating Black people, one, as slaves, and then as second-class citizens. This is completely removed from the curriculum, so we don’t even understand or know where the discipline of Black studies comes from. And so, that is also a political choice. And so I think that it’s just wrong to say that politics had nothing to do with it, when it’s so evident, based on the choices of what remained and what was removed, it’s so evidently shaped by the political atmosphere that we’re in today.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about the Combahee River Collective, which remains in the curriculum, a manifesto of the Black feminist group. You edited How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Explain what it is and how it fits into this Black studies course.

KEEANGA-YAMAHTTA TAYLOR: The Combahee River Collective itself was an organization of Black feminists, Black lesbians that formed in the 1970s. And three of the leading members of that organization put together, wrote a manifesto, essentially, proclaiming the meaning of Black feminism for them, which was really about looking at the ways that the experiences of Black women had been minimized or marginalized over the course of the radicalization of the 1960s, which is to say that, for many, Black politics was seen as a male venture, as a set of politics and organizing that were oriented around the demands of Black men, and the emergent feminist movement was seen to have been dominated by white women. And so, the Combahee River Collective emerges to talk about, really, what are the experiences of Black women.

And they write this manifesto as a way to articulate the need for what they describe as identity politics, and not the kind of identity politics that is talked about today, that is criticized by the right and by liberals today as an exclusionary venture, but really as a way for people who are oppressed and marginalized to have a way to talk about their own experiences, to build a political movement around what they need, because, as Barbara Smith, one of the authors of the statement, said, if we can’t fight for ourselves, then why would we expect anyone else to fight for us? In fact, we know no one else will fight for us. So, it’s a very critical and important statement in the canon of Black feminist studies but also in the canon of Black radicalism.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to bring in Khalil Gibran Muhammad. I wanted to start, though, with Fox News’ Jesse Watters, who said this on Fox News, criticizing the AP African American studies course.

JESSE WATTERS: It’s a very good course. Three-quarters of it is very rigorous and very good, and this is very high-level stuff. And then you get to about 1960 in here, and it’s all activism. It’s all ideology. It’s no history. A good course — chunk of this is really good stuff, and then it goes into white supremacy, patriarchy, abolish the prisons, overthrow capitalism, queer theory, intersectionality. And you’re like, “Whoa! We were going pretty good here,” and then, boom, it hits you with all that stuff.

AMY GOODMAN: And the lower third of this Fox News is “War on 'Woke,'” is what it says. Khalil Gibran Muhammad is professor of history, race and public policy at Harvard Kennedy School. Your response?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Well, here’s the thing. We live in a country where the question of how we ought to make use of our resources, what kind of political structure we should have in order to decide on leadership are all political questions. And we’ve been fighting a question about how to distribute those resources since the very beginning, since 1619, in the debate between indentured servitude and chattel slavery. So, when Fox News suggests that activism to advance a position of a more equitable, a more egalitarian economy — call it “socialism,” if you’d like — or activism in pursuit of an actual multiracial democracy — call that “woke,” if you’d like — is just another way of articulating the same thing the right does, which is to say that we should only be teaching capitalism, we should only be teaching individual freedom. It’s absurd, but it’s good propaganda.

And so, my job, Professor Yamahtta Taylor’s job and Professor E. Patrick Johnson’s job, and the 650 African American studies faculty and their allies who have written a letter in protest to what is going on, it’s our job to actually tell the fullest history and account of the country we actually live in, from the past to the present. That’s our job. And so, it is the job of places like the College Board, who purport to be in a position to develop curriculum to teach students based on what scholars and scholarship says — it’s their job to push back against propaganda. And unfortunately, that’s not what has happened here.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you tell us, Professor Muhammad, about what the College Board is? I mean, the College Board makes the SATs and PSATs. Increasingly, they’re being made optional all over the country. People don’t usually think of this as — I mean, it’s a large corporation that makes a fortune off of this, but now that revenue is threatened. And they also, then, have these AP courses. And if they see that the political climate in this country is going to be banning courses, are they caving to this pressure for their own financial reasons?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Again, we, as scholars, have to ask these questions. You, as a journalist, have to ask these questions. The College Board doesn’t have to answer those questions. They are an independent entity. Now, just a clarification: They are a 501(c)(3), which means they are not a private corporation; they are a nonprofit. They get, literally, tax breaks for what they do. They generate a tremendous amount of revenue, a billion dollars, based on —

AMY GOODMAN: A year.

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: And half a — I’m sorry? A year, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: A billion dollars a year.

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Yeah. Half a [billion] of that comes from the distribution of the AP system, and another portion of it comes from their SAT, and then they have these pipeline programs. So, it is a gigantic entity. The president of the College Board in 2020, according to the public 990, made two-and-a-half million dollars — the CEO, David Coleman — which is twice the salary, the best I know, of the current Harvard president. So, it is not an insignificant entity, and its concerns about his own well-being financially have to be considered in light of these controversies.

AMY GOODMAN: And what about how this leads, not just the elite AP courses, but to what teachers and professors teach all over this country, and their fears? For example, in Manatee County, Florida, teachers have taken to covering up or removing books from their class libraries, after a new law prohibiting classroom material that hasn’t been vetted and approved by so-called certified media specialists went into effect. Teachers found in violation of these guidelines face felony charges, could go to prison. And so, not understanding what this is about, wouldn’t there be massive self-censorship beforehand not to risk becoming criminalized?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Absolutely. This is why what Florida Governor DeSantis is doing is actually shaping national educational standards. This is no longer just about the Stop WOKE Act, that affects what happens in Florida, or in the case where he has now taken over one of the colleges and literally banned any notion of diversity and inclusion, which is now extending to the bureaucracies of the university. I mean, the notion of a chilling effect and self-censorship on what teachers think they might be able to teach is only now being tested. Florida is a laboratory of fascism at this point. I work at the Harvard Kennedy School, and we talk a lot about laboratories of democracy. We talk about city innovation. Well, Governor DeSantis is now ground zero for paving the way for the extension of the elimination of any notion that we live in an open society where we get to debate ideas freely.

And I want to remind people that an AP course is designed to allow students to get college credit. When he and his minions say, “Well, this is about high school students,” well, AP courses are really not about high school students. It’s about them not having to read Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor or E. Patrick Johnson in college, because they’ve already read them in high school. So, the impact on this is national in scope, and we have to consider that in light of DeSantis’s own plans.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the letter that you wrote, along with 650 African American department faculty members, condemning efforts to critique and curtail this new AP course? The significance of this, Professor Muhammad?

KHALIL GIBRAN MUHAMMAD: Sure. Well, I want to clarify: It’s African American studies faculty. And we are represented by Black people, white people, Latinx people, Asian people, everybody. So, everyone is included in that letter. What I want to say is, we’re running out of people in our field who can support this, including people in the letter who are listed in the AP curriculum for credit for participating in the process. It’s becoming less tenable for the College Board to claim that their 300 faculty have weighed in on this, when this number keeps growing, and some of the same people they cite as supporting it have signed this letter.

Professor Yamahtta Taylor has already said strained credulity. I mean, we’re beyond straining credulity. This doesn’t add up numerically, because what I am reading when I’m reading the press reports, when I am reading the releases by the College Board, I’m seeing this gesture to this universe of people, but, in fact, I’m learning that a much smaller number of players participate in the actual crafting of the curriculum. I’m not surprised that the College Board is using this as a communications strategy, rolling out people like my colleague Henry Louis Gates to stand in for what they’ve done. But Henry Louis Gates never appears in any credits in the original curriculum. He only magically appears later on, and then as a spokesperson for this.

So, what our letter attempted to do was to say this — what is happening here in the College Board’s apparent appeasement suggests to us that Ron DeSantis is now fundamentally attacking the most sacrosanct principles of an educational system of an open society, and a frontal assault on academic freedom and democracy.

AMY GOODMAN: And let’s be clear, of course, he’s not just Florida Governor Ron DeSantis; he is clearly a presidential aspirant and will shape the discourse in 2024, if in fact he runs, but clearly thinking that his positions now, he is trying to shape them to appeal to the entire country — which brings me back to E. Patrick Johnson, Dean Johnson. That’s right, dean of the School of Communication at Northwestern University, pioneer in the formation of Black sexuality studies as a field of scholarship. Can you share a message to future AP students? Can you talk about the focus of your work and why you think it’s important for students to learn about Black queer studies?

E. PATRICK JOHNSON: Absolutely. You know, one of the things — going back to something that Professor Taylor says, you know, the suggestion that Black history stops in 1963, or even 1968, is ludicrous. You know, one of the progenitors of what we now think of as Black queer studies is James Baldwin, who was one of the most important thinkers of the 21st century. To leave someone out of the history, of African American history, like James Baldwin is absurd, because he was not only just a fiction writer, a nonfiction writer; he was an activist, and he was also queer. And his thinking has shaped, along with many others — Audre Lorde — what we now think of as Black queer studies. And so, you can’t parse out the intellectual history of Black studies without these important thinkers. So that’s why it’s important for students who are in high school to be exposed to these thinkers, and also to understand the historical context out of which they emerged. Even if they, in their time, weren’t using the language that we use now — i.e. “queer” — they were engaged in conversations and questions around sexuality as it pertains to Black people.

And sexuality as a question, as a mode of thought, also applies to the period of slavery and thereafter. So, I mean, as Black people, we are sexual beings. And so, that’s why it’s important to understand the role that sexuality plays in the history of Black people. If you think about, for instance, the institution of slavery and how sexuality was vital to sustaining that institution, in terms of using Black women’s bodies as breeders or using Black men’s bodies as breeders to maintain slavery as an institution, it’s ludicrous to think or to say or espouse that sexuality is not important when we talk about Black history.

And the other thing I’ll say is, this culture war that we’re experiencing now is not the same culture war that we were experiencing in the 1980s. And the difference is social media. The youth and young people today were born with the access of the world in their pocket through a cellphone. So, even if you take out the Black Lives Matter movement from this course, even if you take out my work and others’ work, people can have access to it. So, we have to be steadfast. We have to be creative, as we always have, to make sure that our young people understand the totality of Black history, which includes the history of Black sexuality.

AMY GOODMAN: Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, we’re going to end with you. February 1st was a beginning and an end. It’s the beginning of Black History Month; it was the funeral of Tyre Nichols. If you can wrap up this discussion by talking about what’s happening today in this country — another attack on the AP curriculum is talking about police violence — and what people have to understand about where we stand today in this country?

KEEANGA-YAMAHTTA TAYLOR: I think one of the reasons why the history — I mean, this is an African American studies course. But why Black history is so important right now is because it speaks to the longevity of both the condition of Black people in this country, one of oppression and marginalization, but it also speaks to the longevity of political struggle. And that is part of what is so appalling, really, about the decision of the College Board in caving in to the right wing on this, whether it was DeSantis or whether it was the general atmosphere, which is to say that Black people were brought to this country as slaves, and then, when slavery ended, there was another 100 years of legal subjugation. So it is entirely consistent that the entirety of Black letters would be consumed with questions of struggle, with questions of activism, with questions of politics.

But also, as part of that are questions about the American project itself, which is really what many of these people are afraid of. And without that history, we don’t understand the intensity of the fury of protest at police brutality. We think that the demands to defund the police or the questioning about the American prison system, or even the suggestion that we don’t have prisons, that we not have prisons, is impetuous, just came up, is a recent phenomenon. No, this comes from a long history of police repression, a long history of judicial misconduct.

And that is one of the reasons why this field of inquiry is so incredibly important. You cannot understand the link between crime and the Black community unless you read Khalil Muhammad’s book, The Condemnation of Blackness, the best book ever written on the topic. You can’t understand so much of Black life today unless you engage with the field of African American history, which is why this is not just some isolated scholastic question, but that it has deep political implications. Black history is about understanding the contemporary moment, not just for Black people, but for the nation as a whole. And that is why this is completely dangerous and why we have to resist these efforts to attenuate our understanding of this history instead of broadening it and deepening it.

AMY GOODMAN: Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, we want to thank you for being with us, professor of African American studies at Northwestern University; E. Patrick Johnson, dean of the School of Communication at Northwestern University; and Khalil Gibran Muhammad, professor of history, race and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. We thank you all so much for this important discussion.

Coming up, we speak to an asylum seeker here in New York who has just been evicted from a hotel where he was staying along with hundreds of other migrants, now the city moving them to a remote terminal in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Stay with us.

Media Options