Guests

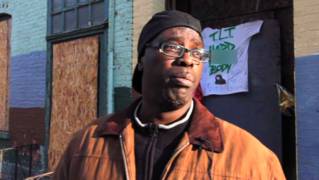

- Kenneth Chamberlain Jr.son of Kenneth Chamberlain Sr., who was killed by White Plains police in 2011.

- Mayo Bartlettattorney for the family of Kenneth Chamberlain.

The city of White Plains, New York, has settled a lawsuit by the family of a man who was shot in his home by police after accidentally pressing his medical alert badge in 2011. Kenneth Chamberlain repeatedly told police he was fine and asked them to leave, but they refused, called him racial slurs and broke into his home before killing him. After a decade of legal action, the family agreed to a $5 million settlement with the city, but the local police association blasted the agreement and said it was not an admission of misconduct. “It doesn’t equate to accountability,” says Kenneth Chamberlain Jr., who now works to challenge police brutality and continues to ask for unsealed records related to his father’s death. “We need actual structural change,” says Mayo Bartlett, a human rights lawyer representing the Chamberlain family, who argues police misconduct must be addressed through legislation. “It has to be something that’s codified in law.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman.

The city of White Plains, New York, has agreed to a $5 million settlement with the family of Kenneth Chamberlain, a Black 68-year-old former Marine shot dead by police in his own apartment. The tragic case occurred early on the morning of November 19th, 2011, when Ken Chamberlain accidentally pressed the button on his medical alert system while sleeping. It was 5:22 in the morning.

Responding to the alert, White Plains police arrived at Chamberlain’s apartment in a public housing complex for a wellness check. By the time the police left the apartment just after 7 a.m., Kenneth Chamberlain was dead. They shot him twice in the chest. A police officer shot him inside his own home. Police gained entry to Ken Chamberlain’s apartment only after they took his front door off its hinges. Officers first shot him with a Taser, then a beanbag shotgun, then with live ammunition.

In a moment, we’ll be joined by Kenneth Chamberlain’s son and by the attorney for the Chamberlain family, but first we want to turn to the remarkable series of audio and video recordings from the morning of Mr. Chamberlain’s death. A warning: These recordings are disturbing. After the White Plains police arrived at Ken Chamberlain’s apartment, he told an operator from LifeAid, that made the pendant, that he wasn’t sick and that he didn’t need assistance.

LIFEAID OPERATOR: This is your help center for LifeAid, Mr. Chamberlain. Do you need help?

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: Yes, this is an emergency! I have the White Plains Police Department banging on my door, and I did not call them, and I am not sick!

LIFEAID OPERATOR: Everything’s all right, sir?

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: No, it’s not all right! I need help! The White Plains Police Department are banging on my door!

LIFEAID OPERATOR: Mr. Chamberlain, go to your door and answer it.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: [inaudible] Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes.

LIFEAID OPERATOR: Open your door for the police, Mr. Chamberlain.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I didn’t call the police. I did not call the police!

LIFEAID OPERATOR: That’s OK. Go to your door and let them know you’re all right.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I stay right there. They hear me. They say they want to talk to me.

LIFEAID OPERATOR: OK, go and talk to them, sir. I’ll stay on the line with you.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I have no reason to talk to them.

LIFEAID OPERATOR: Mr. Chamberlain? Mr. Chamberlain?

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: Yes.

LIFEAID OPERATOR: You pressed your medical button right now. You don’t need anything, let the police know you’re OK.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I’m OK! The police department is knocking on my door, and I—

LIFEAID OPERATOR: Yes, I understand. Go to the door and tell them you’re all right.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I will not open my door.

LIFEAID OPERATOR: Sir, go to the door and tell them you’re OK.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I will not open my door.

AMY GOODMAN: In a separate video, one of the officers, Stephen Hart, is heard hurling a racial epithet, the N-word, at Kenneth Chamberlain during the incident, or they think at this point it might have been him. It might have been another officer. Then you hear Chamberlain say, “They’ve come to kill me.”

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: They have stun guns and shotguns! [inaudible]

POLICE OFFICER: Mr. Chamberlain! Mr. Chamberlain!

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: They’ve come to kill me with that, because I have a bad heart.

POLICE OFFICER: It doesn’t have to happen that way. [inaudible] just have to open the door.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: Get out! I didn’t call you! I did not call you. Why are you here? Why are you here?

POLICE OFFICER: Life alert called us.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: Why are you here?

POLICE OFFICER: Life alert called us.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: They have their nine-millimeter Glocks at the ready. They’re getting ready to kill me or beat me up.

POLICE OFFICER: Open the door.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I’m OK.

POLICE OFFICER: Let them check you out. And then we will leave.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I’m OK. I’m OK. I’m fine.

POLICE OFFICER: Yeah, but I’m not a doctor.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: I am fine!

POLICE OFFICER: No, nothing here.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN SR.: Leave. I’m fine. Now leave. I’m fine.

AMY GOODMAN: Despite Kenneth Chamberlain’s comment that he had a bad heart, White Plains police broke down his door, and they shot him with a Taser. The date was November 19, 2011. Twelve years later, the city of White Plains, New York, has agreed to a $5 million settlement with Ken Chamberlain’s family.

We’re joined right now by Kenneth Chamberlain Jr. and Mayo Bartlett, attorney for the family. He is the former chief of the Bias Crimes Unit of the Westchester County District Attorney’s Office and the former chair of the Westchester County Human Rights Commission.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Kenneth Chamberlain Jr., I am sorry to play all that for you, even 12 years later, the agony that your father went through. And now you have this settlement. Can you talk about what it means to you?

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN JR.: Well, good morning, Amy.

The settlement itself, while — and not just speaking for my family, but for other families, as well — while it may provide some form of redress, it doesn’t really address the broader issues, when you’re talking about police misconduct, brutality and criminality. So, I’ve always said that, yes, this should be part of the process, but it doesn’t equate to accountability.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you arrive at this settlement, and what have the police admitted they did? And were any police officers charged for your father’s death?

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN JR.: Well, no police officers have been charged to date. As far as statements that have been made, I only know of one statement that was made by the PBA, where they said that this settlement in no way is an admission of wrongdoing. And my response to that is very simple: If we’re going to go with that statement that they made, well, there’s one way that we can prove if there has been any wrongdoing or any bias, and that would be to unseal the grand jury minutes, and let’s see what the instructions were to the grand jury in form of charges.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what you’re asking for, more specifically, about the grand jury.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN JR.: So, what I’m asking for is — since my father was killed, you know, in May of 2012, they came back with no true bill. They said there wasn’t sufficient enough evidence to charge the officers in the killing of my father. So, my argument or my question has always been: Well, what were the charges that were put on the table? Did they just put intentional murder? Did they put a hate crime for the fact that they called my father the N-word? Were there any other charges, lesser charges? Criminally negligent homicide? Manslaughter? We don’t know. And because of grand jury secrecy laws, they have not revealed that to us. So, I’ve been asking that those minutes be unsealed now. We know that the witnesses were police officers, so there shouldn’t be an issue with regard to unsealing them.

AMY GOODMAN: Mayo Bartlett, we talked about Officer Hart. He actually died in a car crash — is that right? — and was going to testify, would have testified on behalf of of Kenneth Chamberlain. Can you talk about that controversy around the use of the epithet, the N-word, when they were going after Mr. Chamberlain?

MAYO BARTLETT: Absolutely. Well, Amy, first, he would have testified on behalf of the White Plains city, city of White Plains, but we believe his testimony would have been very favorable, because his testimony would have shown that at the time of the shooting, Mr. Chamberlain was on his back, and they could see the soles of his shoes.

With respect to the epithet, we really don’t know whether he’s the one who has used that slur. So, we’ve been told that by the city, but we’re not certain.

He did die in a car accident, unfortunately. He died before we were able even to take a deposition that would be able to allow him at trial to testify.

AMY GOODMAN: And what happened with Officer Anthony Carelli? Explain who it was who shot Mr. Chamberlain dead.

MAYO BARTLETT: Officer Carelli was the point officer, so he was an officer who was there to cover, to make sure that the other officers would be safe if there was an interaction that became violent. And Officer Carelli is the one who ultimately fired the shot that killed Mr. Chamberlain. But in our estimation, even though he’s the one who was the shooter —

AMY GOODMAN: And to be clear, this was not the Taser.

MAYO BARTLETT: — we think that but for the behavior of the supervisors, he would never have been there. In fact, they were there on a medical call, and on any medical call, it’s hard to believe that law enforcement is the first to arrive. And, in fact, during the entire interaction, no medical personnel were ever given an opportunity to even meet with Mr. Chamberlain or to speak with Mr. Chamberlain.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, this is truly astounding, Kenneth Chamberlain Jr. Your aunt was there — right? — in the hallway, Mr. Chamberlain’s sister, and she told the police that he was suffering from mental health issues, from PTSD, and they had to be very, very careful. Is that right?

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN JR.: Well, my aunt was on the phone speaking to them. It was my aunt’s daughter, my cousin Tonyia, who was in the hallway. And you even hear in the audio when they ask, “Do you have family?” You hear her very loudly say, “Yes, he does.” But they totally ignored her. They acted as if she wasn’t even there.

AMY GOODMAN: You have come to devote your life, Ken Chamberlain, Jr., to say the least, very effecively, to dealing with the issue of police brutality. Talk about the group you formed and how you’ve been dealing with this over the last more than a decade.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN JR.: So, after the killing of my father, we formed the Westchester Coalition for Police Reform. This coalition, you know, the bottom line is, is that we’re looking at transparency. We want to work with local law enforcement agencies in order to build trust between law enforcement and the communities that they serve.

But even bigger than that now, what I want do is create a foundation now in my father’s name, where we’re really going to look at best practices and really push so that the rule of law is adhered to, meaning that the government, its agents and officials will be held to the same set of rules that enables a fair and functioning society. So we’re going to be pushing to put laws in place and different mechanisms, so that, God forbid any other family has to deal situations like this, we’ll have something real in place. And we won’t to be trying to figure out how to put a blueprint together. We’ll have a blueprint.

AMY GOODMAN: Mayo Bartlett, is this one of the largest settlements the city of White Plains has ever made with a victim of police brutality?

MAYO BARTLETT: Yes, my understanding is that this is the largest settlement, with respect to police brutality, from the city of White Plains.

AMY GOODMAN: And, I mean, you are the former chief of the Bias Crimes Unit of the Westchester DA’s Office, also former chair of the Westchester County Human Rights Commission. Do you feel that the situation is getting any better? What kind of regulation of police is there?

MAYO BARTLETT: Well, it’s interesting. In New York state, only 25% of the police departments are actually certified. So, the fact that we have that, and the fact that in Westchester County only 50% are, is a significant problem. It means that there’s no uniform training. You don’t have an expectation that any particular police department is going to behave the way another would.

So, what we’re asking for is unified standards. We think also that it can’t come in the form of an executive order, but we need actual structural change — it has to be something that’s codified in law — and that police themselves should be required to have a license, as do accountants, beauticians, barbers, lawyers, doctors, and that if they engage in certain misconduct, that they would lose that license and not be able to simply resign and go to another police department. Too often we rely on executive orders. And executive orders, although they may be a great stopgap, go away once the next administration comes into power.

AMY GOODMAN: The White Plains Police Benevolent Association has said, “To be clear, the settlement is not a finding of misconduct or wrongdoing by the officers who responded to this call. Our members are asked to place their lives in jeopardy each and every day, as they were on the date of this incident.” I’d like you each to respond, as we begin to wrap up this conversation, beginning with Mayo Bartlett.

MAYO BARTLETT: I think that it’s unfortunate that sometimes PBAs miss opportunities to bring people together. When you consistently find no wrongdoing, irrespective of the conduct, whether you’re watching 20 officers or more beat Rodney King or you’re watching other clear missteps and atrocities, to always say that “We’ve done nothing wrong,” I think, does not invite the conversation that we can have which can bridge the gap and can actually build confidence through transparency.

The city itself made a very different statement, and their statement was that they want to continue to improve the department, they want to have more training, and they want to take steps to make sure that things like what happened to Mr. Chamberlain don’t happen again. I think that that’s a more accurate and helpful statement. And unfortunately, the statement of the PBA does not, in my opinion, benefit the officers who work in the city of White Plains or anywhere else.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Kenneth Chamberlain, we just —

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN JR.: And I would just add to that that —

AMY GOODMAN: We just have about a minute, and I wanted to give you the last word, Kenneth Chamberlain, on that issue and any other you want to address right now.

KENNETH CHAMBERLAIN JR.: OK. Well, I would just simply say that two years ago, the current district attorney conducted a review around the killing of my father to see if there could be any new charges brought forth in this. But that means that they reviewed what the original charges were. So, I would just simply ask that they give us the actual review from Debevoise and unseal the grand jury minutes. And although we know it’s not what you know, it’s what you can prove, I believe that if you do unseal these things, that we’ll see that there was bias in favor of law enforcement. And other than that, may there be accountability for Kenneth Chamberlain Sr., and may there be accountability for all families impacted by police violence.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, again, our condolences. They are never too late, unfortunately. Kenneth Chamberlain Jr., son of Kenneth Chamberlain, shot dead by police in White Plains, in New York, in November of 2011. And Mayo Bartlett, attorney for the Chamberlain family. The city of White Plains, New York, has agreed to a $5 million settlement with the Chamberlain family, the largest settlement around police violence in White Plains ever. That does it for our show. To see our past interviews, go to democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options