Topics

Guests

- Ariel DorfmanChilean American best-selling author, human rights defender, playwright and poet.

We look at the 50th anniversary of what is sometimes called the “other 9/11” — the U.S.-backed coup in Chile, when General Augusto Pinochet ousted President Salvador Allende and inaugurated almost two decades of brutal military rule. Allende died in the presidential palace on September 11, 1973, marking the end of Chile’s first socialist government. During Pinochet’s military dictatorship, more than 3,000 people were disappeared or killed, and some 40,000 more were tortured as political prisoners as Chile remained a close partner to the United States during the Cold War. “We’re still living in some sense under the shadow of Pinochet, and of course we’re living under the gigantic light … of Salvador Allende,” says renowned Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman, who served as a cultural adviser to Allende from 1970 to 1973 before going into exile following the coup. His latest novel, The Suicide Museum, explores the mystery around Allende’s death and whether it was a suicide or murder.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Violeta Parra’s “The Letter,” sung by Víctor Jara, the Chilean singer-songwriter tortured and executed during the Chilean coup. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Today is 9/11. Twenty-two years ago today, about 3,000 people died at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. We’re turning now to look at what is sometimes called “the other 9/11.” Fifty years ago today, September 11, 1973, a U.S.-backed coup led by General Augusto Pinochet ousted Chile’s President Salvador Allende, a democratic socialist who had been elected just three years earlier. Allende died in the palace on that day. Under the Pinochet military dictatorship, which lasted until 1990, more than 3,000 people were disappeared or killed, some 40,000 tortured as political prisoners.

Chile’s current president, Gabriel Boric, commemorated the 1973 coup Sunday with a ceremony in Santiago along with Mexico’s President AMLO, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who he thanked for the country’s historic solidarity with the Chilean people. Both called for strengthening democracy in Latin America. Boric also joined an annual march near Santiago’s La Moneda presidential palace with relatives of victims of Pinochet’s dictatorship. The march was disrupted when counterprotesters attacked it and, according to Boric, quote, “brutally violated graves in the general cemetery.” This is Alicia Lira, president of the Association of Families of Executed Political Prisoners.

ALICIA LIRA: [translated] These 50 years, more than the absence of our relatives, this is an act of homage on the 50th anniversary of the civil-military coup, and we stress “civil-military” because civilians have enjoyed impunity for 50 years.

AMY GOODMAN: Another silent vigil Sunday marked the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup and focused on the role of Chilean women as part of the resistance. Women dressed in black carried signs with pictures of victims of the dictatorship. This is Alejandra Pérez.

ALEJANDRA PÉREZ: [translated] We have fellow women who have been detained, who have disappeared, women who have still not been found, families crying. We have to unite to one day find the truth. I think we deserve it as a people. It is a silent vigil for women.

AMY GOODMAN: Just last month, the Chilean government launched the national search plan to search for people who disappeared during the Pinochet dictatorship. Past governments have discovered mass graves in Chile near former interrogation sites, but they did not properly identify the remains.

For the rest of the show, we’re joined by Ariel Dorfman, who served as a cultural adviser to Salvador Allende from 1970 to 1973. After the coup, Ariel Dorfman went into exile. Today he’s recognized as one of Latin America’s greatest writers. His essays, novels, poems and plays have been translated into more than 40 languages. His new piece in The Nation today is headlined “50 Years After 'the Other 9/11': Remembering the Chilean Coup.” His opinion essay in The New York Times is headlined “I Watched a Democracy Die. I Don’t Want to Do It Again.” His new novel is just out; it’s called The Suicide Museum.

Professor Dorfman, welcome back to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us, though this is a very solemn day, this commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the U.S.-backed coup, backed by Nixon, backed by Kissinger, backed by ITT. If you can talk about what happened on that day? You were in Chile. In fact, when were you last in the Moneda? When had you last seen Salvador Allende before he died on this day in 1973?

ARIEL DORFMAN: First, Amy, I’d like to thank you for having me on this day of mourning and defiance and also resistance and memory.

As to how I lived the coup, it turns out that I was supposed to be at La Moneda that morning and dawn. I was supposed to have slept the night there, because that was one of the ideas, that you had turns where you’re supposed to receive the news whether there was a coup happening. And I switched places with one of my dear friends, who in fact was captured at La Moneda on the 11th. He was tortured and then executed. So, I’m, in a sense, a survivor because of him, or at least so I felt all these years, as I explain in The Suicide Museum, my novel.

A series of other circumstances meant that I didn’t get there, because I slept at my home on the 10th in the evening instead of sleeping at La Moneda. And I was supposed to be called by the minister I was serving. Sort of the chief of staff of President Allende called on a list, and he — nobody called me. And so, I woke up much later, and I wasn’t able to get to La Moneda. And what happened, years later, when I met him and I asked, “Why did you take me off the list? Why wasn’t I called?” and he said, “Somebody had to tell the story.” And, you know, I had already figured out that in some sense that’s why I was spared, or at least that’s what I made sense of the darkness that surrounds all this, you know, the chaos that surrounds all this, that I was meant to tell the story.

And in some sense, I’m doing that right now. And it’s 50 years later. I was 31 years old then. I was almost a kid, you know? Thirty-one [sic] years later, I’m still telling that story, and now I’ve told it again in this new novel. But I’ve been telling it — in fact, I’ve been telling it on Democracy Now! several times already, which is the story of Chile, what happened, why it happened, why that coup happened, but also how we resisted and how we changed history by resisting and how we’re an example of how, if you believe enough in democracy, now and tomorrow and the future, then you will be able to defeat the dictators of now and tomorrow and the future.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Ariel Dorfman, what’s the significance of having the new president of Chile, Gabriel Boric, be part of the commemoration to make sure the world doesn’t forget what happened 50 years ago in Chile?

ARIEL DORFMAN: You know, when Boric was elected, the first thing he did — I mean, when he was inaugurated, really, the first thing he did when he entered La Moneda, that palace that was bombed and assaulted and destroyed and where Allende died, he broke protocol, and he moved on the plaza in front of where the Moneda is, where the presidential palace is, and he went to spend a minute contemplating, in silence, the statue of Allende that has been erected there. And then he went into the building, and he quoted Allende’s last speech and said, “Never again will this happen. We will never again allow this to happen.”

Now, Boric is not, of course, Allende anymore. I mean, you can’t repeat history. But he is a wonderful example of how the new generations have not forgotten. What Boric has tried to do — and it’s very important to mention this — he’s tried to get all the presidents of all the political parties, from the right and the left, to sign a declaration deploring that coup and saying that there will never be a coup again. And the four right-wing parties have refused to sign that declaration. So, he is looking towards the future. He is looking towards the fact that he’s living in a country where 36% of the people still justify the coup. They still say the coup was good. They still think that Pinochet was a great statesman.

We are still living in some sense under the shadow of Pinochet, and of course we’re living under the gigantic light and the lighted shadow, we can call it, you know, of Salvador Allende. And in some sense, I think that for many, many years we’re still going to have that struggle going on. And I feel privileged and honored and humbled, really, to be part of that struggle for memory, to keep that memory alive and not forget what happened there and not forget the glorious thousand days of Allende, where he tried for the first time in history to create a society that was just and equal and liberated without shedding blood.

All the revolutions before that, all of them, from the French Revolution onward, had violence at its origins and had killed many of its own supporters. And we never, never did that. In fact, we didn’t kill not only our supporters, we didn’t kill anybody; we didn’t torture anybody; we didn’t close Congress; we didn’t close the newspapers; we didn’t close the organizations or prohibit the trade unions; we didn’t persecute anybody — which are all things that began to happen immediately on September 11th, 50 years ago. More or less at this time, I was hearing the last words of Allende, and we were being hunted down.

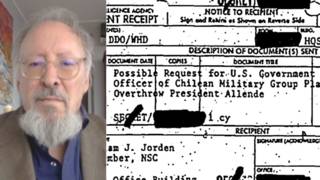

AMY GOODMAN: Can we talk about the U.S. role, which was so significant? Fifty years after Allende’s electoral win in 1970, the National Security Archive released a series of documents showing why and how President Nixon and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger, who just turned 100, sought first to prevent Allende from being inaugurated, and later to oust him from the presidency. In a secret briefing paper on October 18, 1970, just weeks before Allende was to take office, Kissinger wrote, quote, “Our capacity to engineer Allende’s overthrow quickly has been demonstrated to be sharply limited. The question, therefore, is whether we can take action — create pressures, exploit weaknesses, magnify obstacles — which at a minimum will either insure his failure or force him to modify his policies, and at a maximum might lead to situations where his collapse or overthrow later may be more feasible,” he wrote. Two days after his inauguration in Santiago, Kissinger wrote, quote, “The election of Allende as President of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere.” If you, Ariel Dorfman, can talk about the role of the United States, as Kissinger continually threatened, and clearly, though he doesn’t write specifically about this in his books, now that the documents are out, shows how he fought to engineer this coup, at least to support it wholeheartedly?

ARIEL DORFMAN: Well, Kissinger is a war criminal. We all know that. And it’s shameful how he is being lionized constantly by the press, and the bipartisan press in that sense. You know, Kissinger was right. He was right in the following sense: Allende was setting an example, because the guerrillas in Latin America had basically failed — the urban guerrillas of the Tupamaros in Uruguay or the guerrillas that were fighting in the jungles of Colombia or Guatemala. That was not the way which would go forward for Latin America, as it’s been proven now — right? — where we have a series of left-wing governments who have won the ballot box. And he understood very clearly that Allende was more of a threat than Cuba was to him, because Cuba could be — the Cuban example could be suppressed with military aid or with counterinsurgencies. How do you outdo a counterinsurgency against a people who are armed with the vote, who are armed with their consciousness, who are armed with their desire for liberation and love for one another in solidarity? And so, he understood that he had to destroy Allende, because if Allende’s example would have spread through a Latin America, then U.S. interests would have been terribly compromised, which of course was a moment in the moment of the Cold War. So that was it.

Now, let me tell you a little anecdote. Some months, perhaps a month before the coup, there was a truck drivers’ strike. And we went up into the hills of Santiago sort of to do a little bit of military training. It was ridiculous, because we had no military training whatsoever, a group of us. As we went down the hill, we saw the truck drivers, who were having this enormous feast with all the grills and all the stuff which had been hidden away, you know, to sabotage the economy. And they saw us and, of course, had recognized us as Allende supporters. And you know what they did? They took out these sheafs of bills, of dollar bills, and waived them at us. They waved dollar bills at us. I mean, I’m talking about the everyday, right? So, this is something that happened. We know that the CIA was helping the media, that they helped the campaign and that they were just allowing, of course, their military, the CIA-trained or the Defense Department-trained, School of Americas officers to take over. And they engineered, if not the coup directly, they created and facilitated their movements, because they also sabotaged our economy with the invisible blockade. So the United States is very directly responsible for this.

I do want to say the following, however, and I’ve said this over and over again. We should expect the United States to have acted in this way, and we should have expected, and we did expect, the Chilean oligarchy, those who were prosperous in Chile and rich in Chile and had lived off the exploitation of our workers, our intellectuals, our peasants for centuries, we should have expected them to be against Allende, use every dirty tactic against us. That does not signify that we don’t have to think about what we may have done wrong. And we have spent 50 years thinking about this, and the result is our current democracy. What I mean by that is the defeat of Allende is not only the victory of right-wing people and of the United States, it is also a defeat in the sense that it was a failure on our part to do as much as we could. We were much too divided. We were much too sectarian. We did not do what we should have done, what we’ve done since then, which is create the most vast coalition possible for the changes that are necessary. I need to say this because, you know, I deplore what the United States did, but you can’t blame them for doing what they did, though, of course, so many of the American people had such extraordinary solidarity with us. I mean, all the American people should be very proud of what they did in favor of democracy in Chile, even as their government was trying to destroy us.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Ariel, in terms of the impact of the Pinochet years on the rest of Latin America, this period of darkness not just in Chile, but in Brazil, in Argentina, in other countries where military and extreme right-wing governments seized power, what was the impact, for those who are not familiar with that history, on the rest of Latin America?

ARIEL DORFMAN: Well, Uruguay had already had its coup, and a Argentinian coup was coming soon. Soon they got rid of the Bolivian and Peruvian progressive leaders, who were in that country. So, the Chilean example spread.

But, you know, it’s not just in Latin America. You know, Pinochet said in 1981 — in March 1981, he said, “We were alone when we did the coup, but now everybody is imitating us.” What he meant by that was that the neoliberal economics of the Chicago school, Milton Friedman and his Chicago Boys, had used Chile as a laboratory. And that laboratory, what was done in Chile, which is to create a free market fundamentalism, and that example is the one that then is now, in fact, prevalent in the world and is part of the crisis of the world today. So, Chile created this situation where both the repression — and the Condor countries created this repression, which John Dinges has spoken about so eloquently — and that situation of repression was also accompanied by an economic model, which is a model where profit is all that matters, the bottom line is all that matters, solidarity does not matter. And it took over the world. It took over Thatcher’s England first, and then it took over Ronald Reagan’s trickle-down economics, where the idea is to reduce the state to its minimum, except for defense, of course, and surveillance, and not use those resources for the development of the welfare and the happiness of the people.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The Suicide Museum, the narrator is a Chilean American author, playwright and activist by the name of Ariel Dorfman. Tell us why you decided, 50 years after the coup, to write this novel.

ARIEL DORFMAN: Well, you know, I had been thinking for many, many years that somebody — I didn’t think it would be me, of course — would be going back to Chile to find out and investigate whether Salvador Allende had committed suicide or had been murdered. I felt this was the central enigma of our country, because there were many who said, “Oh, he died heroically,” and many who said, especially on the right, they said, “No, he was a coward, and he killed himself” — right? — “rather than face the consequences of the disaster he had led his people into” — right? — “the coup.” And for many years, I kept on thinking, “Well, who would narrate this?”

And then two things happened. One was, I realized that the person who should go back was an avatar of myself, or an alter ego, somebody who was just like me, has my chronology, my family, my wife Angélica, my children, my friends, and go back when I went back in 1990, went back from exile, and create a sort of alternative reality, like in a multiverse, where this person, who is me and wasn’t me — right? — because I treat him with ruthlessness. I treat him like he’s one of those brothers that you’re constantly criticizing. He lies much more than I do — at least I hope that he lies much more than I do. And he’s scared more than I am, I think. So I created this character who’s myself and not myself, because I felt that it was the best way of going into the story of Chile without the limitations of history. You know, I quote an epigraph by Novalis, the German poet of the 18th century. And he says, “The novel is borne of the deficiencies of history.” So, the novel allows us to explore this. I couldn’t — you know, I couldn’t take the story of Allende’s suicide and just do a sort of an essay on it, because that would not tell the story, the deeper story, of Chile. And this allowed me to interview all sorts of people, real and false, and go into that.

The second thing that happened was that suicide, if Allende committed suicide, that is much related to the fact — and I’m not sure about that — it’s much related to the fact that we are committing suicide as a species. So, I had the person who was sending this Ariel Dorfman character — he’s a character, right? — was sending him back to Chile mischievously. He was sending him back to Chile in order to find out if Allende had committed suicide, because this man, this billionaire who sends him there, is worried about climate extinction. He thinks we’re going for the apocalypse, and he needs to create a suicide museum, a gigantic, colossal museum dedicated to the suicides of history, and ending up with the suicide of humanity, so we could wake up humanity to this.

So, those two things came together, and I thought, “OK, this allows me to bring together my two obsessions.” One is Salvador Allende, bring him back to life, rescue him from the iniquities of history, tell his whole story in some sense, and go to La Moneda, where I was unable to go. I go back to La Moneda, but I go back imaginatively through two protagonists, one of which says Allende committed suicide and the other who says he was there when they murdered him. And so I brought this all together in one gigantic, colossal novel.

AMY GOODMAN: And what do you conclude about what happened to Salvador Allende, who died in the palace — this is uncontested — on September 11th, 1973?

ARIEL DORFMAN: But, you know, Amy, I can’t undercut my own characters, because — no, no, seriously. You know, you have to respect them, or they take terrible revenge on you. They come in the night like ghosts. That I have to believe that the characters have got to decide — I leave it up to the people of Chile and the people who read the novel to decide which of the two theses are correct. I don’t want to take sides in that as an author. And if I take sides as an author, I will be undermining my own novel. So, I have my own opinion on this, and I sort of get to that opinion, but as soon as I get to an opinion in the novel, immediately something happens that makes me change my mind. And then I get to another opinion, and I change my mind, which, of course, keeps the tension going, which is what you want in a novel, which is, after all, a thriller, right? It’s a suspense.

But it’s a suspense in relation to the enigma of Allende, and it’s also a suspense in relation to whether this character Allende — I’m sorry, this character Ariel, my gosh — he’s also a character; Allende is also a character — this character Ariel will come to terms with the trauma that he suffered because he survived the coup, and whether the billionaire who sends him there will suffer — will manage to overcome the traumas that he himself has, his secrets that he has. So it’s also a story of a journey of two men trying to figure out, with women — very important, because it’s the empowerment of women, is always central in my work and central in this novel.

I’m always trying to find a way in which I can tell that story so that people see it in a very different light. It’s also sort of a model of what I’d like the world to see, because I say at the end of the novel, I say, Allende is relevant today to the world, because his example, that democracy and more democracy and more democracy is the solution, that everyday people who are protesting today, that they are the clue, and they are the key, really — la clave, I would say in Spanish — the key to how we solve the dilemmas that we’re in, Allende is still speaking to us today. And I continue to think that that is so. I said so in a long essay in The New York Review of Books which came out this week.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Ariel, we only have about a minute left, but I’m wondering — following the coup, you went into a long period of exile. How has that — how did that exile shape you and the writing you’ve come to do?

ARIEL DORFMAN: It changed me significantly, you know, because I opened up to the world, and the world opened up to me. And I had, of course, been brought up in the States. That’s why I speak the English that I do. And that was one of the great weapons that I had. But I spent many of the years just seeking solidarity and seeking to help the people in Chile. And then I began to write. I began to write, and it really created, I think — it created this person you’re looking at as a sort of a bridge. I feel as if I’m a bridge between Spanish and English, between the United States and Chile, between the First and the Third Worlds, between readers everywhere in that sense.

And I think that if I had stayed in Chile, which I really wish I had — I asked the people in Chile, “Let me stay. Let me stay.” And they said, “Ah, you want to write the great novel of the resistance. Get out of here. You’re so valuable outside.” And they were right, you know? So I went out, and it changed me too much. It changed me to such a degree, and the country changed so much, that I ended up leaving Chile after I went back in 1990, which, of course, is also in the novel The Suicide Museum. But I repent of having been in exile, but I don’t repent of the results that happened to me. I’m so sorry for all those who died in my place.

AMY GOODMAN: Ariel Dorfman, I want to thank you so much for being with us, Duke University professor emeritus, author of The Suicide Museum. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Media Options