Guests

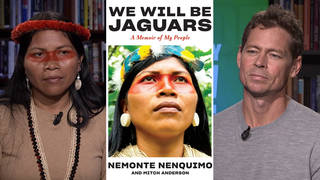

- Nemonte Nenquimoaward-winning Waorani leader in the Ecuadorian Amazon who co-founded Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance.

- Mitch Andersonfounder and executive director of Amazon Frontlines and has long worked with Indigenous nations in the Amazon to defend their rights.

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day today, we look at a recent victory for Indigenous communities in Ecuador, where people overwhelmingly voted to approve a referendum last year banning future oil extraction in a biodiverse section of the Amazon’s Yasuní National Park — a historic referendum result that will protect Indigenous Yasuní land from development. But the newly elected president, Daniel Noboa, has said Ecuador is at war with gang violence and that the country is “not in the same situation as two years ago.” Noboa has said oil from the Yasuní National Park could help fund that war against drug cartels. Environmental activists and Indigenous peoples say they’re concerned about his comments because their victory had been hailed as an example of how to use the democratic process to leave fossil fuels in the ground. “Amazonian women are at the frontlines of defense,” says Nemonte Nenquimo, an award-winning Waorani leader in the Ecuadorian Amazon who co-founded Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance. Her recent piece for The Guardian is headlined “Ecuador’s president won’t give up on oil drilling in the Amazon. We plan to stop him — again.” Nemonte has just published her new memoir titled We Will Be Jaguars: A Memoir of My People. We also speak with her co-author and partner, Mitch Anderson, who is the founder and executive director of Amazon Frontlines and has long worked with Indigenous nations in the Amazon to defend their rights.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

We look now at how the people of Ecuador voted in a referendum to block oil drilling in the Amazon rainforest’s Yasuní Park. But now the newly elected President Daniel Noboa has said Ecuador is “at war” with gang violence and that, quote, “we are not in the same situation as two years ago.” Noboa has said oil from the Yasuní could help fund that war against drug cartels. Activists and Indigenous people say they’re concerned about his comments, because their victory had been hailed as an example of how to use the democratic process to leave fossil fuels in the ground.

Well, for more, we’re joined by someone who helped lead that fight for this referendum and much more. Nemonte Nenquimo is an award-winning Waorani leader in the Ecuadorian Amazon who co-founded Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance. Her recent piece for The Guardian is headlined “Ecuador’s president won’t give up on oil drilling in the Amazon. We plan to stop him — again.”

Nemonte has just published her new memoir titled We Will Be Jaguars: A Memoir of My People. In it, she writes, “Deep down, I understood there were two worlds. One where there was our smoky, firelit oko, where my mouth turned manioc into honey, the parrots echoed 'Mengatowe', and my family called me Nemonte — my true name, meaning 'many stars'. And another world, where the white people watched us from the sky, the devil’s heart was black, there was something named an 'oil company', and the evangelicals called me Inés.”

Well, for more, Nemonte Nenquimo joins us in our New York studio, along with her co-author and partner, Mitch Anderson, who’s the founder and executive director of Amazon Frontlines and has long worked with Indigenous nations in the Amazon to defend their rights.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! It’s an honor to have you with us. Nemonte, I would like you to begin by saying your own name. Talk about the Indigenous nations you are from and the land that you live in, in the Amazon, in Ecuador.

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] Good morning to all of you.

My name is Nemonte Nenquimo. I am a Waorani woman, leader, mother, who comes from the Waorani territory of Pastaza in Ecuador. All women, in general, Amazonian women, are at the frontlines of defense, giving our lives, because we women are more considerate and we worry about our sons and daughters, so that our daughters can have their living space, water, land, knowledge, values, plants, animals, so that we can live well, freely and with dignity. Now our territory is threatened every day. Why should we, as women, be threatened in our territory?

That is why I wrote a book about my resistance, about my childhood, from a child’s point of view. I grew up between two worlds. The missionaries came talking about saving souls, saying that our beliefs were bad. The oil men came to our territory, flying in helicopters, promising development. They did a lot of damage. They destroyed our water. They contaminated our land. They contaminated our people, as well, by disconnecting us from our knowledge and values. And also the governments and the big organizations come to offer to say that they’re going to build national parks, and at the same time they make things worse and take away our territory.

The struggle that we have lived through is very important, so I would like to contextualize it. It is a long story to tell in detail. So, for me, it is very important. As my father says, “Daughter, the more the people of the world don’t know the jungle well, the more they destroy it.” So my story and our culture is oral. That is why I transformed this oral story with my husband, Mitch, into writing, so that the world can understand how we Indigenous peoples are living, connected with Mother Nature, with much love and with much respect.

So, this is a story of resilience, of resistance, so that the people of the world can know the true story of the Indigenous peoples, of all the Indigenous peoples who are living a great, gigantic threat, because this system from here reaches our territory day after day after day. So this message is very important. You can read the book. You can touch and open your hearts and make a real commitment to take action.

What am I trying to say with this? The communities and the civil society here, you have to open your hearts and condemn that the companies do not continue to invest in what harms our territory and what exterminates our territory, our knowledge, our culture. So, from here, we have to begin to reeducate ourselves, not to consume what destroys our health, and to reconnect with Mother Nature, to reconnect spiritually, to love Mother Nature again and to heal ourselves. That is what’s important.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to get into the battle for the law you had passed in Ecuador. But first, the title of your book in the United States that just came out is We Will Be Jaguars: A Memoir of My People. That’s different from the title of your book in Europe that just came out, which is, We Will Not Be Saved. Can you talk about the difference?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] Well, I grew up in two worlds, because the evangelicals came to save the soul, and they brought us diseases, polio. Our grandparents, my grandparents, my aunts died from it. And also the oil companies came to say that they were going to develop the life of the communities, but they destroyed them. And until now, they are contaminating our territory and bringing diseases. And the big oil companies and the governments come with the same intention, without understanding.

That is why I tried to say, “We will not be saved,” as long as they do not listen to the Indigenous peoples, the cosmovisions of the peoples. Sometimes they come with the white man’s structures, thinking they are better, that they have better ideas, bringing development proposals, and they are causing destruction. So that is why I tried to say, because I lived it, since my childhood, confused, and my people, my people were spiritually connected with nature, healing, and the evangelicals were talking about saving us and saying that our connection with nature was bad. So they came to do that, destruction.

That is why I wrote that title, that they cannot continue to treat Indigenous peoples as if we are ignorant, as if we have no knowledge. Indigenous peoples for thousands of years have had knowledge, respect for Mother Nature, love for the Earth. If we women are the land, if they mistreat it, if they destroy it, how are we going to give life to them? How are we going to feed them? So, that is what I’m trying to say.

We Will Be Jaguars. I mean, in our culture, the jaguar is a god. The jaguar helps us to see the vision in our dream of taking care of the territory. If we die, we will continue to live spiritually as a jaguar surrounding our territory, defending it. So, I, as a Waorani woman, led the fight against the government, to fight against oil, to say, “We will be Jaguars, ready, always defending, for our children, for your children and for the planet.” So, that is why I wrote that we will all be jaguars.

And now this book is very special, so that the people of the world can learn to respect and we can work together against climate change. While they are talking here about climate change, there are no answers. They are just making promises, the same politicians, the same representatives making the decisions. There is no space for Indigenous women to take action, to have that space together.

AMY GOODMAN: Mitch Anderson, you’re co-author of this book, and you and Nemo are partners, and you have two little ones, a 9- and a 3-year-old. So, Nemo just explained to us what We Will Not Be Saved means and also what We Will Be Jaguars is. But can you explain, as an American who was born in the Bay Area, why We Will Not Be Saved wasn’t also the title in the United States of this memoir?

MITCH ANDERSON: Yeah. So, the original title when Nemonte and I began writing the book, we had proposed the title We Will Not Be Saved, because Nemonte describes in the book her experience as a young girl watching the missionaries arrive, talking about this white god in the sky trying to save her people’s souls. And she describes all of the harm that was caused. And really, over the course of her life — in the book, she describes it — she learned about this mentality of arrogance that the outsiders, who the Waorani people call the cowori, arrived in their territory with, promising to save their souls, develop their lands, and they caused so much harm. And in the U.K., the title is We Will Not Be Saved.

But when we published the book in the U.S., I think that they wanted to go with a title that was a little less challenging, I think, a little more optimistic, I’d say. And the title We Will Be Jaguars is also a powerful title, because, essentially, you know, Nemonte describes in the book her people’s connection with the jaguar spirits. And even if the oil companies, the governments, the missionaries come in and try to change her people, harm her people, her people will be jaguars, in this life, protecting their lands, and in the afterlife, protecting that very territory that they’re protecting now.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go back to what happened last year, Nemonte, in Ecuador, in the rainforest. On August 20th, 2023, Ecuador voted to halt all future oil drilling in Yasuní National Park. Then Daniel Noboa won the presidency in October, about a year ago exactly. You were one of the leaders of this fight to protect Yasuní. Describe the Yasuní National Park, the movement you led, and then Daniel Noboa’s changing position.

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] Well, the Yasuní is an ancestral Waorani territory and is one of the world’s most biodiverse areas. It gives us oxygen to the planet. To achieve this, the Indigenous peoples united with all the peoples and then with activists, filmmakers, students. We made the people of the cities, of all the civil society understand the importance and also see that throughout the oil exploitation in the territory in Ecuador, in all the country, there has been no development. There has been more corruption, more problems, more death. So it was very evident. And the societies realized that it was very important to protect, to conserve the territory for the future. So this was also the work that we campaigned for.

I also headed Amazon Frontlines. And with other organizations, we made a film so that people could see the Yasuní rainforest and its importance, not only for the Waorani people, but for all the peoples of the planet. Then we achieved this victory in the referendum in Ecuador. In the whole country, we convinced them, and they voted yes to life. That was a powerful sign that I felt, that the people in the cities opened their conscience and opened their hearts and saw what was important was life. So we won. But the president has not met the standards. He should already begin to close and dismantle. And we, the Indigenous peoples, have had enough.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me interrupt for one minute. So, you passed the law first, and this took enormous mobilizing of people across Ecuador. What was the position that Noboa, as candidate, took, after this law was passed, clearly so popular that in order for him to win the presidency, he had to support the bill. Is that right?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] Yes. During the campaign, Noboa said that he was going to respect the Yasuní. But now that he has been elected, he is not respecting it. I would say the politicians, not only Noboa, from my experience, from what I have seen in the presidents, they take office, they make promises, beautiful words in campaigns, but when they are already elected, they do not act with courage and bravery and don’t think of asserting the right of the Indigenous peoples, the right to nature, never. That is why the Indigenous peoples are united, ready to confront them. Our territory is our home. It is a living space for the future and for the people of the planet, and our territory will not be for sale.

AMY GOODMAN: So, the way Noboa is framing it now is they need money to fight drug lords and drug trafficking in Ecuador, and the way to get that money is to bring in foreign companies and to extract more resources to save the country. Your response to that, Nemonte?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] Well, he talks about the economy, the economy, but one day the oil is going to run out. It is not going to be sustaining the future. President Noboa has to care. He has to think about the future. He has to give opportunities. He should be a more important leader in the world that can change and leave the oil in the ground and see the alternative, not the mentality of consumerism, but another form of mentality, a change, to see what can be generated in the future and to see that the Indigenous peoples are respected, that Mother Nature is respected to stop climate change for the world. But many times, the leaders never think that. They just want money now, and there is no solution. That is not the solution for future generations, because Noboa has a great opportunity, because he is a young president who could change the world.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how do you force that to happen? You are Waoroni leader. You are one of the leaders of the movement that passed a bill that went in the other direction. How do you make that happen now?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] I could say to this that all societies have to take action. Do not let the Indigenous peoples be alone fighting for life. What we Indigenous peoples do, we are the solutions. We are at the frontline. So people from here have to start by not investing in the companies that are damaging the territory, the forest, in general, in all of Latin America. Two, no more promoting the propaganda that the solution is oil, but to see another alternative for energy. Third, the mentality here has to change, to not consume more of the many things that are harmful. By change, I mean really open your heart, reconnect with Mother Nature, reconnect spiritually, heal again. That is the solution. If people here in the cities continue to consume, it is the same. It will affect the Amazon, while we, the Indigenous peoples, are at the forefront.

Enough is enough. We are not going to stop fighting. We are going to be there standing up. We are going to be at the front as warriors and as jaguars. But here, as long as they do not change, as long as they do not stop consuming, it is still going to affect the Amazon. Even if the oil companies do not come, it is going to affect it. So, for me, the work is here, to pressure the politicians, to pressure the companies, not to consume what is harmful, but to heal in the cities.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re here in the midst of a presidential election in the United States, perhaps the most important. You’ve got the main parties, the Democrats versus the Republicans. On the issue of immigration, they vie with each other, or, you might almost say, agree on many points, is shutting down the border to immigrants coming from Mexico and south from there, including Ecuador. Can you make a direct link between thousands of Ecuadorians and people overall in the Amazon fleeing their land, their countries, because of environmental destruction, because of poverty, because of violence?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] I think that this has happened a lot in the last few years, because the climate crisis in general in the world is very serious. And we must not let that happen. We have to awaken the conscience of the people of the city.

Why are people not happy? People are fleeing their countries because it not only affects Ecuador, because this system of consumption here provokes armed conflicts. It provokes oil extraction, because the wider world needs that to plunder. They need money.

That is why we have to look, to balance, to reconnect, to feel again the peace that we want in the society, because Mother Earth is suffering these phenomena that affects all of us. And people are not realizing it. The politicians, with the great power they have, are not realizing it, because they are disconnected. They are not connected with the Earth. They are not connected with their spirituality. They don’t have love. They don’t have love at all.

So, people, society, we have to get together, promote, socialize, unite, so we can solve it. We are not going to wait for the government to make the decision in our home. We are not going to allow the government to govern our blood, our territory. So the responsibility is for all of us. That is what I’m trying to say. The responsibility is not for the Indigenous peoples.

Why do we have to live in our territory daily under threat, day after day? Because the system does not stop, this mentality does not change, this heart does not touch deeply. So the work is here, in the big cities. I try to say, as an Indigenous woman, I see that. As an Indigenous woman, I am seeing that the problem is not in the Indigenous territory. The problem is here, this system. And all of us have to stop the system. That is the message. As long as we do not know life, which is the most important thing, we are going to destroy it. Mother Earth is not waiting for us to save her. Mother Earth is waiting for us to respect her, to love her again, to heal her again. That is the society we have to heal.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you are here in New York. You’re here for Climate Week, and you’ve been to Climate Weeks here in the past, though you spend most of your life in the Amazon. What has it been like for you to be here with thousands of people alongside scores of world leaders coming and addressing the United Nations? Do you feel there’s been any progress over the years you’ve come and joined with thousands of activists from around the world on the issue of dealing with the climate catastrophe?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] As an Indigenous woman, we in the communities live as a collective. We women are always at the forefront, because we are concerned about the well-being of the whole community. We are a collective, and we make sure that everything is well. We are protectors, guardians, mothers.

But what I see about climate change when I arrive here as an Indigenous woman, I look, and there’s no space for Indigenous women where they can talk to the politicians. I see that space, and the same politicians are representing, talking, making decisions for the territory, taking resources for the territory, and talking about how to save the environment. But there is no serious way for Indigenous peoples to be allowed at that table, to listen and make decisions, to make a commitment of will and respect. There is nothing. Politicians create their spaces and make their decisions, and that is not going to stop climate change.

What I’m seeing very strongly is that civil societies are raising their consciousness. They are waking up. That’s a good sign. I mean, because I work with the collective communities, so the work and the role is ours, as civil societies, we have to unite. We have to put pressure on the politicians to look at us, to open their hearts and to become aware and to take the issue of climate change seriously. If, while we are in this space, the Indigenous people come and present their stories, the same politicians come to make decisions and sign resolutions and agreements. This is not a solution for me. It is sad.

AMY GOODMAN: Mitch Anderson, you have worked on this issue for years. In the early 2000s, you were with Amazon Watch. You’ve spent a lot of time since then, well over 15 years, in the Amazon. You, together with your partner Nemonte, have founded Amazon Frontlines. But as you come back up into the United States, to your home country, do you see any progress being made? And also, as a person who can see the Amazon from here, from where your family and community was, to where you are living now with your children, with your new community, what do you feel is the biggest misunderstanding we have of the Amazon?

MITCH ANDERSON: Yeah. So, I’ve been living in the Amazon with Nemonte and her people for the last 15 years. Most of the oil that’s produced in the Amazon destroys the rivers and the forests and then is shipped up to California to be refined in California, and then it’s distributed to gas stations around the country and made into jet fuel. I don’t think that people in the United States truly understand that and truly understand what Nemonte is saying about our consumption patterns and our systemic addiction to oil and how it is devastating Indigenous cultures, their life ways and also their territories.

You know, in the 1960s, American oil companies discovered oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon and the Peruvian Amazon, made deliberate decisions to dump barrels of oil into the rivers, millions of gallons of oil and wastewater, in order to save money, and created this massive public health crisis. For the Ecuadorian government at the time, they thought that this was going to be their salvation. It was going to take them out of, you know, subdevelopment and poverty. But what it’s created over the last 60 years is disparities economically, inequalities, corruption, massive environmental contamination, poverty.

And, you know, I think that what Nemonte, her people, youth climate activists in Ecuador have done is they’ve shown the Ecuadorian people, they’ve told stories to the Ecuadorian people, they’ve helped wake up consciousness and say, “Look, 60, 70 years of oil development, and look where we’re at right now. We need to keep the oil in the ground. We need to protect the most biodiverse forests in the world. We need to wake up our imagination, think about economic alternatives, think about regeneration.”

And, you know, the win in the Yasuní, in the most biodiverse forests in the world, is that. It’s this model of climate democracy that is an inspiration for the entire world. And, you know, at Amazon Frontlines, with Nemonte, we’re a collective of Western activists and Indigenous leaders that are looking to stop the oil industry, the mining industry, the loggers, not let them into the forest, create permanent protection zones, but also work with Indigenous communities to get their land back, because, essentially, Indigenous communities are the ancestral owners of nearly half the remaining standing forest in the Amazon. They are only 5% of the world’s population but protect 80% of the biodiversity on our planet. Indigenous peoples are the owners of 40% of the intact ecosystems worldwide.

And so, what we’ve seen here at Climate Week is civil society is waking up. Indigenous peoples are leading the marches. Indigenous peoples are sharing their stories, sharing their positions, amplifying their values. But what we’re seeing is that politicians, world leaders of companies are still really committed to sucking the last drops of oil out of the forests, out of the oceans. And we can’t afford that.

AMY GOODMAN: And what has this collaboration been like for you, writing the book together? It’s Nemonte’s memoir, but you did it together, We Will Be Jaguars: A Memoir of My People.

MITCH ANDERSON: So, over the last 15 years, Nemonte and I, her people, Amazon Frontlines, the Ceibo Alliance, we’ve won a lot of battles. We’ve beat back the oil industry, protected a half-million acres of forest, set a precedent to protect 7 million acres more, helped lead a movement to protect Yasuní and keep 726 million barrels of oil in the ground.

Yet the threats keep coming. Oil companies, the mining companies — the government right now in Ecuador is making designs to do another oil auction, leasing out millions of acres of territory to international oil industry, right at a time when we all know we need to stop oil production. We need to keep the oil in the ground.

And so, when Nemonte told me that her dad had told her that the Waorani people have always known that the outsiders destroy what they don’t understand, and her dad told her that it’s time for her to write her book, to write a story of her people as an act of resistance, to give the world a chance to learn about Indigenous peoples, to understand their connection with the forest, to understand what’s at stake, Nemonte asked me to be a collaborator. You know, we’re life partners. We’re partners in activism. We’re co-founders of Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance. And she asked me to join her, too, in writing her story.

She comes from an oral storytelling tradition. And so we spent years together in the mornings, you know, first light, on the canoe, walking in the forest, and I would listen to her tell me her stories. Some stories went back to the beginning of time, thousands of years, hundreds of years, her first memories as a young girl. And, you know, my mission was to figure out a way, with Nemonte, to touch the written word with the spirit of the oral storytelling tradition of her people. And it was a really beautiful process. And we think that — we think that — Nemonte told me that she thinks that her ancestors would be proud of the story that we told.

AMY GOODMAN: Nemonte, take us on this profound journey you take us on in your book, We Will Be Jaguars. Tell us first about where you were born in Ecuador, in the Amazon, one of the last places contacted by missionaries. You’ve said, “The authors of our destruction are the very ones who preach our salvation.” But start off by talking about your face and the images on your face that, for our radio audience, it is a hue of red across your eyes, from temple to temple, and what that means, and also your headdress.

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] As a child, I grew up in two worlds, very pretty, beautiful, the feeling as a child of seeing the evangelicals flying around, bringing us the word of Jesus, and also seeing our grandparents around us, healing us with plants. So I was a very curious girl. I wanted to discover. I wanted to understand who were these people, the white people, and the grandparents. Who are they? So I grew up in a very nice, very beautiful time, because in our territory, we still lived collectively at that time. Our chakra, our river, our way of living was free, in a big space.

Our culture is the achiote. On the forehead, we paint our eyes to protect from bad energy, and also beauty for the women, who can paint that part of the face and show the identity of our origin as Waorani women.

The crown is from the feathers of the macaw bird. And for us, the bird is very sacred. And they were very valuable for our ancestors, and we still believe that. Macaws fly. They sit in a tree and start to communicate amongst themselves, and then they plan where they’re going to fly to look for food. So, when you wear the crown, it represents a woman leader and that you’re united with your family to protect your home and your communities.

And the necklace means that you are a leader. It represents power, the power of women. That’s our culture. This seed is called pantomo. There are many of these plants in the jungle. And for us, it protects us from bad energy and also gives us good vibes, good energy. And when you go to a ceremony and when you go to meetings, you wear this.

So, in our culture, it’s like 50 or 60 years since we’ve had contact with the world, with the outside world. And, of course, there is a new generation, and we think about how to describe our knowledge, and our grandparents are already dying. So we have to teach our own culture to the young people, to young leaders, so that they continue to protect their territory and having their own language.

And so, it’s very important for us to go back, to have our own education system, our own traditional education, and at the same time learn about the outside education system and learn about how to use this knowledge to protect our territory, so there’s still forests. And if the forest is healthy, we’re going to be healthy. But if the forest is sick and is contaminated, then we’re going to start to get sick, and we are going to disconnect ourselves from our knowledge, our language, and we are going to lose everything, as has happened to other peoples who have been disappearing for 500 years. And we do not want our territory and our life to disappear. We want to continue being Waorani with the knowledge of two worlds, valuing our principles.

AMY GOODMAN: So, take us on the journey from New York, what it will mean for you to go back home to the Ecuadorian Amazon. How long does it take? You will fly in to Quito, the capital of Ecuador?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] Yes, I can describe. To get to my territory from here, from New York, you have to fly to Quito. From Quito, you need to take a bus or a car five hours more to a small town that is called Puyo, Pastaza, and from there, four hours more to the end of the road, where other neighboring Indigenous Quechua people live. And from there, you have to take a canoe, a boat, go down the river to get to where the Waorani territory begins.

And then you get to the communities of Daipare, Quenahueno, Toñampare, where I was born and grew up as a child. And then I moved further down. My dad took me further deep into the jungle, to a community that is called Nemompare. And now my dad and my house are in Nemompare. It is the most far-out area and is an area with big trees, beautiful trees, ceibo trees. And there are lots of birds flying around, macaws and other birds. And you can hear the songs of the birds, small and big. And you can see the fish, the anaconda, the jaguar growling, the red monkeys screaming in the mountain. And it is very beautiful. And when you arrive at night and when you look up at the stars and you see the light of the moon, it’s very beautiful.

And the territory of us is big. There are three provinces: Pastaza, Napo, Orellana. And we live collectively in the territory. But in one area, there’s already an oil company operating, in the Yasuní, where our Tagaeri and Taromenane brothers live in voluntary isolation.

We’re trying to defend our right to have our homes and to have our space without extraction, without contamination, where we can live happily and with dignity. And all that we do in my community to protect ourselves benefits not only our tribes. We benefit the oxygen. Eighty percent of the diversity in the lungs of the world comes from our territory. So, that’s my message, that even though you are here in New York City and elsewhere, we feel connected to you.

We need to start to work together collectively and as women. And I work a lot with women in my community, because, as women, we’re in the front of this fight. We take care of our bodies, of our health. So, that is my message. I bring the spirit of the jungle woman. And my message, for that very reason, is in the book. I hope you all read this book and reconnect with Mother Nature and connect to love yourself and connect spiritually, to heal us together, to confront the threat, because it is not going to stop. I am sure the threat is not going to stop. So, what we need is to articulate as women. Between Indigenous women and non-Indigenous women, we need to work together.

AMY GOODMAN: You have just won a major award here in the United States, which you will soon be receiving, the Hilton Humanitarian Prize from the Conrad Hilton Foundation. It’s two-and-a-half million dollars to your group, Amazon Frontlines. Can you talk about what that means to you, what you’re planning to do with that?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] Well, this recognition is very important for me. It’s very important to show what we’re doing, as well as our partners, that we can provide resources to the Indigenous communities, because we’re on the frontline of the fight against climate change. And this will help us to grow our organization and build our structure and to fight this threat that is coming every day.

This recognition is not a solution, but it is going to help make us visible, show our fight, and also show it to other actors. The threat is very strong, and it can’t just be the Indigenous people in front of the fight. So the whole world needs to come together and push for changes for the future.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Mitch, you are co-founders of Amazon Frontlines. The significance of this for your organization?

MITCH ANDERSON: Yeah. So, Amazon Frontlines, we’re a collective of Indigenous and Western activists. And for us, the Hilton Humanitarian Prize is a validation of our model. It’s a validation of Indigenous leadership on the frontlines. It’s a validation of the importance of Indigenous stewardship of their lands. It’s a validation of the world recognizing that to confront the climate crisis, Indigenous folks need to be seen, platformed, empowered, given the resources they need to continue to protect against all these threats.

It is significant resources that we’re going to be receiving, and we’re going to be investing those in the frontlines for Indigenous communities that are waging battles to stop the oil industry, to stop the mining industry. And we’re also going to be using the award and its visibility to raise more resources, to scale our work, to scale our impact and to ensure that we can protect the entire Upper Amazon, one of the most biodiverse forests on the world, a storehouse of carbon. It’s still a carbon sink, and it’s one of the most culturally diverse places on our planet. And so, yeah, we’re just extremely proud, extremely grateful, honored, humbled, and we’re going to get the resources to the frontlines.

AMY GOODMAN: As we wrap up, if you can look directly into the camera right there and share your message with the world?

NEMONTE NENQUIMO: [translated] My message is the forest and Mother Earth are important. We need to come to love it, and we need to connect to it. We need to go back to connecting, and we need to heal our bodies, because we give life. The message that I’m bringing is that we Indigenous people are the minority, but our territory is bigger, as well as the diversity that we are giving to the life of the planet.

So, the threat is coming day by day from the system, and our responsibility is collective. It is not only Indigenous peoples and Indigenous women leaders who have that responsibility. We have to connect with women who are not Indigenous, so we can unite to act for our well-being and the well-being of our children.

AMY GOODMAN: Nenquimo is a Waorani leader in the Ecuadorian Amazon who founded also the Ceibo Alliance. Mitch and Nenquimo co-founded Amazon Frontlines and just published a new book. It’s titled We Will Be Jaguars: A Memoir of My People. We’ll also link to Nenquimo’s recent piece for The Guardian headlined “Ecuador’s president won’t give up on oil drilling in the Amazon. We plan to stop him — again.” This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options