Topics

Guests

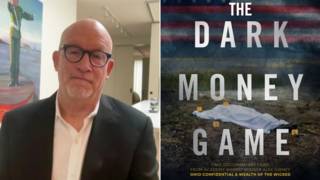

- Omar Dahieconomics professor at Hampshire College and director of the Security in Context research network.

Links

As Syrians celebrate the fall of the Assad regime after more than five decades of iron rule, many are grappling with the enormity of what has happened to their country, with nearly 14 years of war leaving much of the country in ruins, killing over 350,000 people and displacing 14 million more. Meanwhile, foreign powers, including Israel, Turkey and the United States, have carried out strikes across parts of the country, and Israel has invaded and occupied additional land in the Golan Heights. For more on the monumental changes underway, we speak with Syrian American political economist Omar Dahi, the director of the Security in Context research network, who has been involved in several peace-building initiatives since the start of the conflict in 2011. He says many Syrians have “mixed emotions” about this moment, celebrating the end of Assad while mourning the immense human cost of the war and confronting the difficult road ahead to rebuild the country. “Politics is finally possible,” Dahi says.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show with Syria and the aftermath of the historic collapse of the Assad regime. Israeli forces are continuing to attack key military sites, airports and army air bases in cities across Syria, including the capital Damascus. In just the last 48 hours, Israel has carried out 340 airstrikes, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. A resident from Qamishli in northeastern Syria described the strikes that took place Monday night.

ABDEL RAHMAN MOHAMED: [translated] The strikes happened at night. We went out after hearing the sounds, and we saw a fire there. Then we realized that Israel struck these locations. We didn’t get a break from Turkey, and now Israel came. Israel has been striking the area for a while now.

AMY GOODMAN: Turkey and the United States have also continued to strike targets in Syria since the lightning offensive led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS.

In a message posted to Telegram Tuesday, the rebel commander Ahmed al-Sharaa vowed to hold senior officials in the Assad regime accountable for, quote, “torturing the Syrian people,” unquote.

As different factions of armed groups vie for power and their international backers defend their interests, Syrians are grappling with the enormity of what has happened to their country and what comes next.

In 13 years of war, over 350,000 people have been killed, according to the United Nations, over 14 million displaced. President Bashar al-Assad has now fled to Russia, where he’s been granted political asylum with his family. Syrians are adjusting to the new reality of life after 50 years of rule by the Assad family, Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar.

MAHMOUD HAYJAR: [translated] Today we don’t give our joy to anyone. We have been waiting for this day for 50 years. All the people were silenced and could not speak out because of this tyranny. Today we thank and ask God to reward everyone who contributed to this day, the day of liberation. We were living in a big prison, a big prison that was Syria. It’s been 50 years during which we couldn’t speak, nor express ourselves, nor express our worries. Anyone who spoke out was detained in prisons, as you saw in Sednaya.

AMY GOODMAN: For more on the dramatic changes in Syria, we’re joined by Omar Dahi, Syrian American economics professor at Hampshire College, director of the Security in Context research network, where he focuses on political economy in Syria and the social and economic consequences of the war. He was born and raised in Syria and involved in several peace-building initiatives since the conflict began. Professor Omar Dahi joins us now from Amherst, Massachusetts.

Professor, welcome to Democracy Now! First, your response to Assad’s departure, him fleeing with his family to Russia, and what this means for Syria?

OMAR DAHI: Hi, Amy. Thank you so much for having me.

Yeah, I’ve been watching, like many others from outside the country, in shock and disbelief in this past two weeks, and with mixed emotions in many ways. First, shock and disbelief at the collapse of the Syrian regime and the way it happened after 13 or more years of conflict, where there were frontlines that were frozen for the past several years, but suddenly they disappeared. Of course, incredible joy at the personal level and also for millions of Syrians who were directly hurt by the regime, both through the violence of the war, the displacement, the killings and tortures that were taking place, as well as previously, before the war.

It’s been incredible watching the scenes of the liberation of prisoners from prisons like Sednaya, which have been referred to, I think correctly, as “human slaughterhouses.” It’s been incredibly moving to see people celebrating in the streets, people saying that they can finally go home, they can finally speak their mind. So, all that has been really a joy to watch and witness as we kind of see the sequence of events unfold with the — you know, Bashar al-Assad fleeing to Russia.

Thankfully, this process, which we can talk more about, happened, finally, with as minimal bloodshed as possible, even though there was plenty of bloodshed over the past years. But in the way it had happened, it actually provided a possibility for positive change, at least at the moment.

But this joy is also tempered with lots of other feelings, as well, primarily the costs at which this happened. And I would say the costs are the human costs, that you outlined, which may be even more in terms of the people killed. Entire generations have been destroyed. There is a generation of Syrians that grew up in displacement, in refugee camps, the destruction that happened to the country. All the human cost and the physical cost, I think, it’s hard to say that it was not too high. It’s impossible to say that it was OK that all this happened.

There are other costs, of course. The other cost is the loss of sovereignty of Syria, which has been a process ongoing for 10 years. Syria was occupied and invaded by the United States, by Turkey, on the opposition side. And on the Syrian government side, it drew on its allies to defend itself, Russia and Iran, which came to place the regime in a position of dependency. So, there were multiple foreign types of occupations in the country, which we see what is happening now in the Israeli airstrikes as a continuation of that loss of sovereignty. And I think this is something that Syrians have to grapple with.

There are other costs of the war, as well. There are the empowerment of actors that are not acceptable to a wide variety of Syrian society. Not that there isn’t some backing for them, particularly because they have a certain legitimacy for many Syrians because they fought the government. But the current government in power or the current, you know, HTS is not acceptable to large parts of Syrian society, and there’s already warnings that it’s acting as a de facto power, and people are warning against that.

And, of course, there’s the final thing, which is that this is tempered by the regional context, which is the ongoing Israeli genocide in Palestine that is empowered by the U.S. And we’ve seen over the past couple days a complete destruction of what was remaining of Syrian Army military assets by Israel, with complete impunity.

So, all of those, we’re trying to take all those contradictions together — joy for the people, joy for the moment that many millions had dreamed of, which is the departure of the Assad family from power, and the feeling that politics is finally possible in Syria. Despite all these contradictions, there is a chance for political life to resume. There’s a chance for advocacy for a collectively better future. And this is something that we all have to try and hold and support.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Professor, I’m wondering if you could talk briefly about your own family’s history. In the 1990s, your father helped smuggle out names of political prisoners, many of them accused of belonging to the League of Communist Labor, yet the Ba’athist party and the government of your country often talked about being socialist.

OMAR DAHI: Yeah, this was a kind of a spur-of-the-moment post that I did on social media to share these documents that I received after my father passed away three or four years ago. And basically, my father was a lawyer and was among two or three or maybe four lawyers who stepped up in the 1990s to defend a large group of political prisoners, many of them communists, many of them who were accused of being members of the Muslim Brotherhood. They were basically detained without a trial — or not even just a trial, but without a formal charge. They were accused of belonging to this outlawed party of Communist Labor, which was accused by the government of mounting an insurrection against it in the late '70s and ’80s. So, most of those who were detained were detained in the 1980s. They had been disappeared. Their families didn't know anything about them. Most people didn’t know — like many of the people we’re discovering in Sednaya prison today, were not aware whether they were dead or alive or their whereabouts.

So, my father would basically meet with some of those prisoners, when allowed to do so. And really, it was the courage of the prisoners to assemble a lot of this data, to write down their names, their dates of birth, their professions, where they were — when they were arrested, what’s their charge, where they were being held — mostly, in this case, in Sednaya prison — and also if they were in — you know, they needed medical attention, they were traumatized or they were injured in some way.

And I asked my dad why he did this, actually, because, you know, there was no sense that these prisoners would be freed. So, most of them ended up being put on trial en masse and convicted. So, he told me that he had no expectation of justice at that time, but that he felt it was necessary to do it, to use any opening and any chance to expose the hypocrisy of the government, for the same reasons that you mentioned, that he didn’t expect them to actually be — you know, receive a fair trial, which they didn’t, but there has to be a chance to basically put the government’s declared principles against its actions and expose the government.

So, this was a historical document that I was kind of moved to share when the images of the prisoners who were being released from Sednaya. Most of those names in those documents have either, unfortunately, passed away or were released from the prison, so I didn’t expect that there would be some of those people actually there. But, yeah, that’s why I shared that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, I wanted to ask you also — you mentioned the foreign presence in Syria. Hasn’t the country, effectively, during this civil war been already partitioned, with Turkish troops creating a buffer zone in the north, the Israelis not only recently, in the past few days, entering Syrian territory, but conducting military operations in the territory previous to that, with the Kurds backed by the U.S., ISIS still controlling portions of territory, and the Russian bases in the country? Do you have any sense of the integrity of the country being reconstituted anytime soon?

OMAR DAHI: I don’t think so. I think it’s going to be a long-term struggle, and partly because of the reasons you mention, because this is something that has been happening for a decade, and there are kind of entrenched interests that have developed, not just in terms of a foreign occupation, but in terms of the connection of various parts of Syrian society and their ties to those countries in ways that they’ve come to basically be affiliated or allied with them. And this is reminiscent, for people who observe Syria, of the post-independence period in Syrian history, when Syria was a site of struggle by external powers because it was weak, it was politically divided, and various regional powers basically came to have significant influence in the country through Syrian political elites. This was transformed by the Assad family and the Ba’ath Party in ways that actually flipped this around, where Syria consolidated its power and projected its power, at least regionally. But it came at a price, I think, that was high and unsustainable, particularly for Syrian society.

Now this is actually completely shattered. And I think there’s going to be an attempt to rewrite the history of the Syrian conflict in ways that pin the blame completely on the Assad regime, which I don’t think is the case. I think they are primarily at fault for this, not just because of their governance, which was brutal and tyrannical and maintained an exclusive monopoly on power for decades, without recognizing any dissent, without recognizing any political opposition; not just because of their reaction to the uprising when it first started, where they completely closed down any meaningful political transition; but also because even after they won the war, they spent many years refusing any political initiative to reconcile, after they had, with the help of Russia and Iran, won the war, basically. So, the frontlines had been frozen for many years.

But all the other international actors also contributed to the destruction of the country. I think there were ways in which, you know, this fragmentation didn’t just imply an obvious loss of sovereignty in the abstract sense, but also destroyed the economy and fragmented the Syrian national economy. It created kind of perverse war economies in the country. And as you said, Israel has been bombing Syria for the past decade. This bombing escalates after the collapse of the government. They further invaded Syrian territory, and we saw the incursions and the devastation that took place in the last couple days.

AMY GOODMAN: If you can talk about who Mohammed al-Bashir is, the man who’s been appointed the temporary prime minister right now of Syria, and also HTS, its role, listed as a terrorist movement by the U.S., the EU, the U.K. and Turkey — the U.N. special envoy for Syria told the Financial Times that international powers seeking a peaceful transition in the country would have to consider lifting this designation — who Abu Mohammad al-Julani now — his birth name is Ahmed al-Sharaa — is?

OMAR DAHI: Yes. Well, I mean, I’m not an expert on Ahmed al-Sharaa’s personal history. Some of that has come out in recent days about his birth in Syria. He claims he was radicalized by the Palestinian intifada, and he joined al-Qaeda in Syria and Iraq.

And Hayat Tahrir al-Sham is basically a splinter group from al-Qaeda that had basically come — it was based in Iraq and then came back to Syria after the uprising started. And there was a period of time, which maybe your audience will remember, when Syria fragmented into various militias. And there was just as much infighting among those militias, among themselves, between the opposition groups, just as much as they were fighting the Syrian government. So, basically, groups similar to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham were fighting each other. And then there was a period of reconsolidation, particularly in the aftermath of the attack on ISIS, and the kind of permanent or the, you know, more or less, consolidation of Syria into various spheres of influence, with a U.S. presence and Kurdish-led political and military groups in the northeast, Turkish control in the northwest. And under the areas that were generally under Turkish influence, there were areas that were directly tied to Turkey and areas in which Turkey had influence, and this is the area that came to be consolidated by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. So, they have a bloody history not just prior to the war, but actually during the war, with respect to even other opposition groups, and kind of, basically, you know, during the time of the rule in the province of Idlib.

Right now and during these past two weeks, there’s been a lot of positive signs in terms of the way they approached the collapse of the Syrian regime, the signs that were verbal, the signs that were actually in actions in terms of trying to protect all government institutions, all public institutions, despite the fact that there have been incidents of looting and sabotage in various ways, but at least they’ve been trying to speak of a national interest in some ways. That, of course, has to be put to the test. There’s already critiques of their rule, because they unilaterally imposed a transitional government on Syria, which most Syrians would reject as something that they don’t have the authority to do. It’s also happening in a context where, of course, Syria is still under economic sanctions, so you’ve had devastation from many years of the war, and you’ve had also devastation of Syrian society because of the crippling economic sanctions, primarily imposed by the U.S. and the European Union. So —

AMY GOODMAN: We just have 30 seconds.

OMAR DAHI: So, all of that is really going to be, basically, coming into play over the coming days, basically, and months. And we’ll see how the regional context basically influences what’s happening domestically.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you so much for being with us. Of course, we’re going to continue to follow what happens with Syria. Omar Dahi, Syrian American economics professor at Hampshire College and director of the Security in Context research network.

Coming up, we go to the West Bank to a new report by B’Tselem. As thousands of Syrians are being released from Syrian prisons, we’ll look at a new report on Palestinian prisoners in Hebron, in the occupied West Bank. It’s called “Unleashed: Abuse of Palestinians by Israeli Soldiers in the Center of Hebron.” Back in 20 seconds.

Media Options