Guests

- Reed Brodywar crimes prosecutor.

Human Rights Watch is hailing a “monumental victory” after a Swiss court convicted former Gambian Interior Minister Ousman Sonko for crimes against humanity committed under the dictatorship of Yahya Jammeh. Sonko was sentenced to 20 years in prison for his role in torture, illegal detentions and unlawful killings between 2000 and 2016. He is the second ex-Gambian official convicted in Europe for international crimes committed in Gambia, after a former death squad member received a life sentence in Germany last year. In Part 2 of our discussion with by Reed Brody, a war crimes prosecutor and author of To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré, he discusses these developments in detail. We also speak with Reed about the International Criminal Court and Gaza.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Human Rights Watch is hailing a “monumental victory” after a Swiss court convicted former Gambian Interior Minister Ousman Sonko for crimes against humanity committed under the dictatorship of Yahya Jammeh. Sonko was sentenced to 20 years in prison for his role in torture, illegal detentions, unlawful killings between 2000 and 2016. He’s the second ex-Gambian official convicted in Europe for international crimes committed in Gambia, after a former death squad member received a life sentence in Germany last year.

We’re joined now by Reed Brody, war crimes prosecutor, author of To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré. His recent piece for The Nation is headlined “Who’s Afraid of the International Criminal Court?”

Reed, I want to talk more with you about the International Criminal Court and Israel and Palestine, following up from Part 1 with our discussion with Ilan Pappé, but first let’s talk about Gambia, which has received much less attention. Put it in geographical, in geopolitical context for us, for people who haven’t been paying attention to what went on in the Gambia.

REED BRODY: Sure. So, Gambia is a small country, the smallest country on the African continent, almost entirely surrounded by Senegal. In 1994, Yahya Jammeh, a military coup, and then became the elected president. He was in power from ’94 to 2017. And his rule was marked by the killing of dissenters, by shooting on demonstrators, by attacks on the press. Also, and we had once on your show Toufah Jallow, a woman who had been personally raped by Yahya Jammeh. He had an entire system of bringing women to work for him or to live with him who he then abused. He carried out witch hunts. He had a presidential alternative age treatment program in which he forced people to abandon their HIV medicines, and he treated them personally, and many people died.

And finally, in 2017 — 2016, late 2016, there was an election, which he lost, to his surprise. He refused to give up power, but the people of Gambia rose up in the #GambiaHasDecided movement. And backed by the regional organization ECOWAS, which sent in troops, Yahya Jammeh fled the country and is now living in exile in Equatorial Guinea. And his victims have been seeking justice ever since. And it happened that we had finished the Hissène Habré case in neighboring Senegal, the final judgment on appeal.

AMY GOODMAN: Hissène Habré from Chad.

REED BRODY: The Hissène Habré — so, as you know, I worked for 18 years with the victims of the former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré, who took refuge in Senegal, and we prosecuted him there under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which we’ll talk about in a minute, the idea that some crimes are so heinous that any country in the world can, and sometimes must, bring their perpetrators to justice if they’re found on your territory.

Just as the Hissène Habré case ended in Senegal, we got a request from a Gambian victim, who said, “Can you — we would like to do what the victims of Hissène Habré did,” which is also poetic, because the Hissène Habré’s victims asked us to help them do what the victims of Augusto Pinochet in Chile had done. Anyway, we, together with the Chadian victims and their lawyers, we actually went to Gambia, had a first meeting between Hissène Habré’s victims and Yahya Jammeh’s victims. And the victims in Gambia began a “Jammeh to Justice” campaign.

And the government which had come into power, a democratic government, organized a truth commission, a very powerful — it was almost like a soap opera as victims and perpetrators testified on national television to how they carried out murders, telling, “Yahya Jammeh gave me the orders,” and as people like Toufah Jallow talked about how they were raped by Yahya Jammeh. And after those very — I mean, you’d go around Gambia, and people would be listening to the truth commission on their radios, on their TVs. And after those very powerful testimonies, there’s been now the truth commission recommended that Yahya Jammeh and his henchmen be prosecuted.

Up until now, the only prosecutions that have taken place have been these prosecutions under the theory of universal jurisdiction of Gambians who had been caught outside of the country. So, as you mentioned, there was a trial in Germany of a member of the Junglers hit squad, Bai Lowe, who was convicted for murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. This case was the former interior minister, actually, Ousman Sanko, who for 10 years was in charge of much of the repressive apparatus of Yahya Jammeh. And he was found in Switzerland. The organization TRIAL International filed a criminal complaint against him. And so we just had this trial that I attended in Bellinzona, Switzerland, in which he was convicted of crimes against humanity.

AMY GOODMAN: Why in Switzerland?

REED BRODY: Because that’s where he was found. He was actually — he went to Sweden. He applied for asylum in Sweden. He didn’t get it. Sweden sent him back to Switzerland, which was his first country of entry into Schengen. And so, then he was in Switzerland. A journalist told my friends at TRIAL International, “The interior minister of Gambia is here.” And TRIAL International filed a criminal complaint against him. And so, he was arrested and has now been prosecuted.

And there’s actually another trial coming up in Colorado. Another member of Yahya Jammeh’s Junglers hit squad, Michael Correa, was arrested many years — I think it was 2018, 2019, was found in Colorado. And he was actually picked up on a visa — on immigration charges. And we, together with other — with the Center for Justice and Accountability and other NGOs, pressed the U.S. government not to deport him, but to prosecute him, under the Alien — under, actually, the torture statute, under this principle of universal jurisdiction. And so, his trial for torture back in Gambia under the principle of universal jurisdiction —

AMY GOODMAN: And is he Gambian?

REED BRODY: He’s — yes, he’s a Gambian member, a leading member, actually, of Yahya Jammeh’s hit squad.

Now, all of this, and I’ll just finish with the — the big news, though, is what’s going on in Gambia itself. So, after the truth commission, which recommended prosecutions, there’s been this expectation on the part of Gambians and the international community that the Gambian government would move forward now. And so, just this month, the Gambian government set up a special prosecutor’s office to take the cases from the truth commission and is now making — actually, I was in Gambia recently, as they are drafting the statutes of a new special court between Gambia and ECOWAS to try the worst crimes of Yahya Jammeh’s regime and also to request Yahya Jammeh’s transfer from Equatorial Guinea.

AMY GOODMAN: And what is Equatorial Guinea saying? And why did he go there?

REED BRODY: Well, it’s very interesting. Equatorial Guinea is, you know, a dictatorship, is an oil dictatorship. It’s probably one of the most corrupt dictatorships in the world. And basically, when Yahya Jammeh lost the elections, he didn’t want to leave. The people rose up. The ECOWAS troops were coming in. He negotiated a deal to go — everybody negotiated a deal. It was — he would go to Equatorial Guinea and live there. And actually, the president of Equatorial Guinea has said, you know, “My job — I took him in to save the situation in Gambia. You know, I don’t believe he should be — you know, now people should start coming after him.”

But one of the ideas of having this new court is to — it’s going to be a regional court. And it’s going to bring in the regional powers — Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal. Also, the worst massacre of the Yahya Jammeh period was actually 59 migrants who were trying to get to Europe, who were beached in Gambia. Forty-four of them were from Ghana. And they were all killed. And actually, we —

AMY GOODMAN: When was this?

REED BRODY: This was in 2005. And actually, we found the one survivor who jumped out of the truck before they were all killed, and who went back to Ghana and actually went from village to village in Ghana to the families, to get them together to campaign for justice. So, we feel that if a request comes from a regional court, with the support of Ghana — I’ve met with the Ghanaian president, who was foreign minister at the time the 44 of his citizens were killed. We believe that a regional court bringing in these other big powers, it would be very difficult for the president of Equatorial Guinea to say, “No, we are not going to hand him over to an African court.” So, we see this as an area where we see — so far, the only trials have happened outside of the Gambia, but they have also created even more and more of an expectation that something should happen now in Gambia. And finally, after a very long delay, the government seems to be moving forward.

AMY GOODMAN: And how do these actions — I mean, everything from Hissène Habré being charged in Senegal, what’s happening in Gambia — relate to the International Criminal Court?

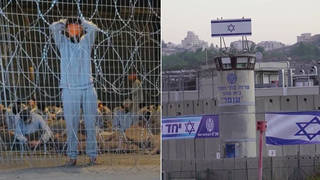

REED BRODY: Well, it’s very interesting. I mean, these are two separate tracks of justice. And I have to say, you know, we have to be very sober about the International Criminal Court. In 20 — in over 20 years, it has never actually captured, prosecuted and convicted a state official anywhere in the world, not just in the Western world, but anywhere in the world. I mean, it is a court of last resort, that doesn’t have a police force. And so, the only people actually convicted at the International Criminal Court so far have been rebels, five African rebels. The International Criminal Court, as we discussed, is not likely to get its hands on Vladimir Putin or Benjamin Netanyahu anytime soon.

What’s interesting about these other cases — so, you have the 1998 watershed year for international justice. In July, the International Criminal Court is created. In October, Augusto Pinochet is arrested. And so —

AMY GOODMAN: In Britain.

REED BRODY: In Britain. So, the former dictator of Chile —

AMY GOODMAN: Where he went for medical treatment.

REED BRODY: Right. The former — well, he had medical treatment. He didn’t go there for medical treatment, but he had medical treatment while he was there. The former dictator of Chile goes to London, is arrested on a warrant from a Spanish judge, Baltasar Garzón, for crimes committed back in Chile. And so, this was really the opening for this victim-led international justice. And what makes that interesting is that was the case that was brought in Spain by Chilean victims, that was moved forward by Chilean activists. And, you know, when — I mean, ultimately, Pinochet, the House of Lords in Britain, which was then the apex court in Britain, ruled that despite his status as a former head of state, he had no immunity to charges brought under the basis of universal jurisdiction for torture. Ultimately, he was sent home. He was sent home to a very different Chile, which had been energized by his arrest. And he actually died under house arrest with cases against him mounting. But what was very interesting then was that was a case brought by victims.

And then — I was at the time at Human Rights Watch — people started coming to us from all over the world: “We want to do that.” We saw, when Pinochet was arrested, that we had a tool in international justice that victims and activists could use to bring to book people who seemed out of the reach of justice. And that’s when the Chadians came to us and said, “We want to do that.” And that’s when, you know, the Gambians go, “We want to do that.” And one of my mentors, a woman named Naomi Roht-Arriaza, wrote about just how these victim-led cases are so much more powerful, because they can be copycatted, because they are acts of imagination and decentralized at will. So, there’s a — I said before that the ICC has actually never convicted any state officials. But in those 20 years, a lot of state officials have been convicted at national courts, like — or transnational courts, like in the Chadian dictator in Senegal. There’s a trial going on right now in Guinea of the former head of state, Dadis Camara, for a massacre. I mean, we’ve seen Charles Taylor. We’ve seen — you know, there are cases going on in —

AMY GOODMAN: Charles Taylor, Liberia.

REED BRODY: Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia, who was prosecuted for crimes actually committed in Sierra Leone, by a special court. But what we see is that justice for mass atrocities is — and then you have these universal jurisdiction cases, like the one we’re just talking about of the Swiss court prosecuting a Gambian. There are over a hundred universal jurisdiction cases in the world. There are cases against Israeli leaders.

I mean, in fact, one of the problems, of course, is that once you attack the U.S. or Israel, these laws tend to contract. I mean, I was in Belgium, I mean, in the long saga of the Hissène Habré case, in which we filed the complaints against his former Chadian dictator in Senegal. Senegal threw out the case. We went to Belgium. Belgium had — Belgium and Spain used to have the biggest universal jurisdiction laws in the world. The defendant didn’t even need to be in the country for you to file the case. What happened to those laws? The Belgian law was very good when the defendants were Rwandans or Africans. But then there was the case against Ariel Sharon for the massacre in Sabra and Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon. And then there was the case against George Bush, father, for an air raid shelter during the first Gulf War. And I was in Belgium when Donald Rumsfeld came to Belgium.

AMY GOODMAN: Then the defense minister.

REED BRODY: Then the U.S. secretary of defense, came to Belgium and said, “If NATO leaders cannot come to Belgium without worrying about some crazy arrest warrant or something like that, then we’re going to have to move NATO outside of Belgium.” And the law fell like a house of cards.

And the same thing happened in Spain. The law, the Spanish universal jurisdiction law, that was used by Baltasar Garzón in 1998 to send an arrest warrant against General Pinochet, who wasn’t in Spain at the time, who was in England; and that was also used for cases in El Salvador, the Jesuits, who were — the military leaders who prosecuted the Jesuits, who were — who killed the Jesuit priests, who were prosecuted in Spain; an Argentine torturer who was arrested and prosecuted in Spain. But once that law, the Spanish law, was then used in a Tibet case related to China, in an Israel case, and then a case against the United States, that law also collapsed.

So, we see that there is — there are over a hundred universal jurisdiction cases going on in different countries around the world. But again, when they get to sensitive countries, the United States in particular, we see a pushback.

AMY GOODMAN: Speaking of the United States, though we discussed extensively the ICC chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, pursuing arrest warrants for Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, Yoav Gallant, the defense minister, and three Hamas leaders, I wanted to go to what happened at the State Department on Monday. The State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller claimed that the International Criminal Court does not have jurisdiction to try Netanyahu. He was questioned by Associated Press reporter Matthew Lee.

MATT LEE: Where do the Palestinians go to seek redress?

MATTHEW MILLER: Israel does have open investigations, a number of open investigations — we made this public when we released our report on National Security Memo 20 — including some investigations that have become criminal investigations into conduct by members of the IDF. That is the first instance for judging whether someone has committed a war crime or a violation of IDF code of conduct. That’s one of the reasons why we have concerns about the ICC. The ICC is set up to be a court of last resort. If a country isn’t properly holding itself and its personnel accountable, that’s when the ICC comes in, not in the middle of the process, as they have done here. …

MATT LEE: So, let’s just focus on jurisdiction for a second. Who does have jurisdiction here?

MATTHEW MILLER: So, the government of Israel has jurisdiction.

MATT LEE: Over the occupied —

MATTHEW MILLER: We have — we have jurisdiction —

MATT LEE: Over Gaza, which is not entirely occupied.

MATTHEW MILLER: They have jurisdiction into looking at the actions by their military personnel.

MATT LEE: OK. So, the Palestinians, if they have a complaint —

MATTHEW MILLER: We

MATT LEE: — they have to bring it to Israeli courts?

MATTHEW MILLER: We — we have jurisdiction, and we —

MATT LEE: You have jurisdiction?

MATTHEW MILLER: With the use of our equipment —

MATT LEE: I’m sorry. How do you have jurisdiction?

MATTHEW MILLER: With the use of our military equipment that we have provided.

MATT LEE: Matt, how do you have jurisdiction?

MATTHEW MILLER: If you look at the Leahy law, if you look at —

MATT LEE: No, that’s — that’s not jurisdiction in a criminal process. That’s jurisdiction in a —

MATTHEW MILLER: Not in a criminal process, but it has to do with the determinations that we make and the policies that flow from it.

MATT LEE: Yeah, but that’s not jurisdiction.

MATTHEW MILLER: So, but, Matt, long term, you are right that we want to see —

MATT LEE: You used work for DOJ, Matt. Come on.

MATTHEW MILLER: You are — it is — it is not —

MATT LEE: There is no — the U.S. does not have jurisdiction here.

MATTHEW MILLER: There are different — I wasn’t referring to criminal jurisdiction, Matt. There are different ways to look at this. Long term, we agree with you that the Palestinian people should be a state that has the — and have the ability to make these determinations. But that’s not where we are today.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s the State Department spokesperson Matt Miller being questioned by Associated Press’s Matthew Lee. Can you just take that apart for us and talk about —

REED BRODY: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: — what Lee is pursuing here?

REED BRODY: So, there’s a lot to be said there. First interesting thing is that the traditional U.S. position is that the ICC doesn’t have jurisdiction because Israel is not a state party. And interestingly, they’re not making that argument today. And I think they’re not making it because of Russia, because they were so celebratory when the ICC exercised jurisdiction over Vladimir Putin, who’s also a nonstate party, for crimes committed on the territory of Ukraine.

AMY GOODMAN: And not only did they celebrate it, it came out that the Biden administration had instructed all agencies to participate in gathering information and documents for the ICC to help support that indictment.

REED BRODY: That’s right, which was a huge change in position. And it was — they overruled the Defense Department, actually. The Defense Department did not want to do it, because they did not want us to create a precedent for the ICC looking at actions of nonstate parties.

But here, they’re not making that argument. Here, they’re making what’s called the complementarity argument, which is Israel has a functioning judicial system, the ICC is a court of last resort, Israel can take care of it. In principle, that’s a correct argument. But it’s not enough for Israel to have a good judicial system. Israel must be investigating Benjamin Netanyahu and other Israeli leaders for potential war crimes of starvation, of persecution, of extermination, of intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population. And that, they’re not doing. So, it’s not enough to say, you know, “We’ve got good judges.” But are you investigating this? And obviously, it’s almost a tautology that Israeli courts are not going to investigate state policy of how this war is being conducted.

I mean, it’s the same argument, frankly, that we made to Barack Obama, when, after George Bush, you know, I mean, the Bush administration — Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Tenet — have a case to answer, for torture of Muslim prisoners, for renditions of Muslim prisoners to places like Syria and Libya and Egypt, for the — I mean, for Guantánamo, things like that. And, you know —

AMY GOODMAN: For the invasion of Iraq?

REED BRODY: For the — well, that’s interesting, because that’s the crime of aggression, which at the time was not so much — you know, there was no court that had jurisdiction at the time over the crime of aggression, which I’d be happy to get into in a second. But, you know, the U.S. said, “Well, we have a justice system. They’re prosecuting Lynndie England and these people from Abu Ghraib.” And, you know, we saw recently even they can’t even get the contractors from Abu Ghraib. But the idea is not, you know, to go after, as Israel may be doing, some rogue soldier, you know, who is a sadist. No, the idea is to go after state policy. And Israel is not looking at the state policy, just as the United States never examined the Bush administration policy of torture, of rendition and things like that.

In terms of aggression, the U.S. aggression against Iraq, you know, at Nuremberg,, which we always go back to, aggression was considered the worst crime, the crime of crimes, the crime that allows the war crimes and the crimes against humanity actually to happen. But in the post-Nuremberg development of international law, obviously, neither the United States nor the Soviet Union was very interested in seeing that become a core international crime. The International Criminal Court has jurisdiction over aggression, but, finally, only over cases in which the country that commits the aggression has previously agreed to the court’s jurisdiction over aggression, which is why we can’t prosecute Vladimir Putin and Russia for their aggression in Ukraine. I mean, the United States — and there has been a move by Philippe Sands, by very forward-thinking international jurists to have a special court that would look at Russian aggression in Ukraine, which is a wonderful idea, except that the United States, you know, invaded Iraq. Other countries do this. And the only reason you can’t prosecute Vladimir Putin right now for the aggression in Ukraine, or Israel for the aggression in Gaza, potentially, is because the big powers didn’t want courts to have that jurisdiction.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you about the liability of the Biden administration when it comes to supplying the weapons. I mean, in the United States, we have something called felony murder. You could be the one that shoots someone, but you are also charged with felony murder if you’re the one that provides the weapon, and then another person shoots another person. What about that when it comes to the ICC and other international bodies?

REED BRODY: Sure. I mean, this is, I think, you know, a really very important discussion. We’ve seen now at the International Court of Justice, the other court in The Hague — we recently saw Nicaragua bring a case against Germany, alleging that Germany was complicit in violating the Genocide Convention for supplying arms to Israel.

AMY GOODMAN: And they went after Germany, which doesn’t supply as many as the United States —

REED BRODY: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — because Germany is a signatory to the ICJ?

REED BRODY: Because Germany has — so, the ICJ, the International Court of Justice, which is the court between states, as opposed to the ICC, which is a criminal court — the ICJ is a consent-based court. So, cases can only go to the ICJ in instances where the state has previously consented to that kind of jurisdiction. And the U.S. has not, and Germany has. The ICC — the ICJ, in its ruling, and on preliminary measures, said, “Well, you know, in fact, Germany has practically not been giving anything to Israel. On the facts, we don’t see that Germany is now giving lethal weapons to Israel. But we remind everybody” — but in a very strong statement at the end of the decision, they reminded states of their responsibility, as they transfer arms and things to Israel, not to — to make sure that those weapons are not used to violate the Genocide Convention, to violate the Geneva Conventions.

So, then you also have individual responsibility, which is more of what you asked. I mean, you can be, you know, an accomplice to murder, aiding and abetting murder. I mean, Charles Taylor, who we mentioned earlier, he was the president of Liberia, but he was convicted by a special tribunal for crimes committed in Sierra Leone, a country that he never put his foot in, because he supplied the material means to the Sierra Leone rebels to commit crimes. I was on your show once talking about the potential liability of Henry Kissinger for crimes committed in countries that he never went to, but where he was instrumental in supplying arms as killings were going on. Of course, Amy, you know very well the situation of East Timor. But there’s also, you have Bangladesh, for instance, where the Nixon — Nixon and Kissinger knowingly transferred arms to the murderous Pakistani Army, over the objections of the State Department, over the objections of the local ambassador, as they were carrying out killing sprees.

So, what you have to show in an individual case is that a certain individual is complicit in a strict legal sense of aiding and abetting, that they’re giving the means to carry out a crime, and it is — that is positively furthering the carrying out of a crime. It’s the same as, you know, if you’ve got a guy walking down the street and going on a shooting spree, and he runs into the ammo store and says, “Give me more ammo, I need to go out and kill more.” You’re liable. You’re liable as an accomplice. And that’s the kind of liability that, for obvious reasons, has not really been developed in international law as much as it should.

AMY GOODMAN: So, I want to go back to something we talked about in Part 1 of the ICC discussion, and that is The Hague Invasion Act. Republican senators have cited what’s actually called the American Servicemembers’ Protection Act, a bill that’s being called The Hague Invasion Act because it could be used to justify a military operation against the ICC in The Hague if it prosecutes American officials or soldiers and they’re brought there, to free them.

REED BRODY: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what this is all about.

REED BRODY: Well, in the — you know, after the U.S. lost, basically, in the drafting of the Rome Statute, that governs the International Criminal Court, after it became clear that the International Criminal Court could prosecute not only the citizens of countries that were state parties, like most countries, but could also investigate crimes committed on the territory of countries that accepted jurisdiction, then it became, all of a sudden, theoretically possible that the ICC could prosecute an American. And so, when the Bush administration went into — I think the Bush administration went into overdrive. And they got — first of all, they got, I don’t know how many countries, but close to 80 or 90 countries to sign bilateral agreements, treaties with the United States, that they would never turn over an official. And then Congress passed this American Servicemen’s Protection Act, that, among other things, gave the president the authority to take any measures necessary to free any American or allied person who was in the dock in The Hague.

And, I mean, we’ve seen — I mean, this was the policy of the Bush administration. Then Obama came in and — yeah, then Obama came in and took a more friendly policy towards the ICC, I would call it good neighbor policy towards the ICC, supported the ICC, you know, in its work generally. Then you had — but then, when the prosecutor of the ICC, Fatou Bensouda, began investigations into alleged American crimes in Afghanistan, and finally, after much delay, began an investigation into Israel-Palestine, then the Trump administration went back and introduced sanctions.

AMY GOODMAN: Against Fatou [Bensouda], who was the chief prosecutor.

REED BRODY: Against Fatou, who was the chief prosecutor, against her, against some of her staff and against the ICC.

AMY GOODMAN: And you now have Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton saying, “My colleagues and I look forward to make sure that neither Khan” — now the chief prosecutor — “his associates nor their families will ever set foot again in the United States.”

REED BRODY: Well, first of all, I don’t think he can do that diplo — I mean, the United Nations is in New York. And so he has to allow, at the very least — I mean, even Iranians and everybody gets to go to the United Nations; otherwise, the United States would not have the United Nations at a certain point. You know, I think this just goes back to this policy of exceptionalism. I mean, international justice is wonderful when it’s the defeated, you know, armies of Germany and Japan, when it’s African warlords, when it’s, you know, opponents of the West, like Vladimir Putin or Slobodan Milošević. But once you start, you know, looking at the United States and its allies — and, of course, a lot of this is done in the guise of democracies. How can you talk about a democracy in the same — but democracies commit war crimes. And you don’t have a democracy exception. You don’t have an American exception for war crimes. Vladimir Putin commits war crimes, he should be liable. An American, a French, a German commit war crimes, they should be liable, whether they’re a democracy or not.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you compare President Trump and President Biden when it comes to the ICC? And this is not just of historical interest? Of course, they’re running against each other for president.

REED BRODY: You know, President Biden — look, I work very closely with the U.S. ambassador for war crimes, Beth Van Schaack. I think she’s a wonderful woman. She has been very instrumental in promoting justice in Gambia, in — Liberia is now setting up a war crimes court — in Latin America, I mean, all over the world. I think there’s just a — you know, there’s just a blind spot — that’s not a blind spot, obviously. Just a line is drawn in the sand when it comes to the United States and Israel. And I think the U.S. has been trying, under the Biden administration, to be friendly to the International Criminal Court, to support the International Criminal Court in its work. But, you know, there’s a line that even Democratic administrations are not going to cross.

AMY GOODMAN: And you live in Barcelona. You live in Spain. Can you compare Spain’s response to Israel-Palestine to the United States’?

REED BRODY: Well, of course, the Spanish government came out with a full-throated endorsement of the ICC’s decision — of the prosecutor’s decision. I mean, the Spanish government has — which is a center-left or left coalition, has been very supportive of Palestinian demands. They have said that they are going to recognize the state of Palestine. Together with Belgium and Ireland, they have been the states within the European Union that have been the most on the forefront of trying to have a progressive two-state solution in the Middle East. So, I think, you know, we’re seeing — I mean, actually, many people have been making charts of the responses to the warrants. And, I mean, we see Spain really on the top of this. You have other countries, like England, like the United Kingdom, on the other side. You have countries in the middle who don’t — you know, who take note. But it’s really only the United States, Israel, I think Hungary, who have really come out in strong reaction against these warrants.

AMY GOODMAN: Of course, you have Gustavo Petro in Colombia, who also —

REED BRODY: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — took a very strong stance against what Israel is doing.

REED BRODY: You know, this is the thing. I mean, for those of us who believe, you know, in justice, for those of us who believe in human rights, you can’t have an Israel. Look, I mean, this goes back to something that I feel like my entire life as a human rights advocate, as a human rights activist, has had to confront, is the Israel exception to human rights. Human rights here, human rights there, but there’s always been a blind spot and, I mean, this — you know, this overdrive to protect Israel from any possible international inquiry. Now, it is true. I mean, I remember when I first went to Geneva, to live in Geneva and work in Geneva, in 1987. And I went from a country, the United States, where you couldn’t criticize Israel, to a place in the United Nations where I, frankly, saw a lot of antisemitism. And I felt like people could just get away with saying a lot of things about Israel. But, you know, over the long haul, I mean, what I have seen — I mean, I was in — at the World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa, in 2000, just before the — was it 2000, 2001?

AMY GOODMAN: 2001, right before —

REED BRODY: 2001, right before 9/11, at which, you know, the Israel-Palestine became — you know, really almost sunk the conference, in which actually the NGO document that was put together accused Israel of genocide, accused Israel of — I mean, brought back Zionism and racism. And as Human Rights Watch’s delegate there, we actually walked out. We actually sat — no, I walked out. We disassociated ourselves with that document. I personally did that, to say — and yet, because of just our mere participation and my mere participation in that conference, I have been a whipping boy for a certain Israel, you know, pro-Israel lobby for the last 20 years. They never forget that Reed Brody was at the infamous World Conference on Racism, even though Human Rights Watch actually disassociated itself from, you know, any anti— even language on Israel that today probably fits. So, I mean, I think the entire, you know, human rights — you don’t believe in human rights if you have exceptions, if it’s an American exception, if it’s a Palestinian exception, if it’s an Israeli exception. And I think throughout my entire career as a human rights activist, one of the big realities has been the blind spot, the Israel exception to human rights principles.

AMY GOODMAN: And do you feel that’s changing right now?

REED BRODY: I think it is. I think we’re seeing a — you know, I would go back, actually. The founder of Human Rights Watch, I should mention, Bob Bernstein, actually resigned at a certain point from Human Rights Watch and wrote an op-ed in The New York Times saying that Human Rights Watch should not be investigating countries, democracies, like Israel. That’s not what it’s for, again. I do see that changing. And I have to say, I mean, at the one point, I mean, I’m glad that it’s changing, obviously. At the other point, as a Jew, as somebody — I just — I mourn the fact that the state of Israel is doing what it’s doing, and that people around the world associate Jews with what’s going on in Israel. I mean, I find that very — that’s why it’s so — for me, it’s so wonderful, particularly here in the United States, not so much elsewhere in the world, but particularly here in New York and the United States, to see Jews in the forefront of the protests against, Jewish Voices for Peace and others in the forefront of the protests against the Israeli policies in Gaza and the West Bank,

AMY GOODMAN: Reed Brody, war crimes prosecutor, author of To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré. He’s got a recent piece in The Nation headlined “Who’s Afraid of the International Criminal Court?” We’ll link to it at democracynow.org. To see Part 1 of our discussion on the International Criminal Court with Reed and the Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, go to democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options